Miscellaneous Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Epithelial Type: Breast, Liver, Sinonasal Tract

Mithra R. Baliga

Sudha R. Kini

This chapter focuses on some infrequently occurring neuroendocrine neoplasms of epithelial type, namely neuroendocrine tumors of the breast, neuroendocrine neoplasms of the liver, and sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinomas (SNNECs).

NEUROENDOCRINE NEOPLASMS OF THE BREAST

Primary neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) of the breast are defined as a group of tumors that exhibit morphologic features similar to those of neuroendocrine tumors of both gastrointestinal tract and lungs. These include well-differentiated NECs (carcinoid tumors) and poorly differentiated carcinomas (small cell/oat cell carcinoma and large cell undifferentiated NEC). The World Health Organization (WHO) classification (2003) of breast tumors addresses carcinoid tumors as solid-type NEC. While focal neuroendocrine differentiation may be noted in many ductal and lobular breast carcinomas, the term neuroendocrine carcinomas is to be applied when more than 50% of the tumor shows differentiation by expression of neuroendocrine markers. Breast can also be involved secondarily from neuroendocrine neoplasms from extramammary sites.

CLINICAL AND IMAGING FEATURES OF NEUROENDOCRINE NEOPLASMS OF BREAST

Primary NECs of the breast are extremely rare tumors constituting 2% to 5% of all breast carcinomas.

The clinical and imaging features of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the breast mimic those of other tumor types with no notable or other specific differences in presentation. Patients often present with a palpable nodule, which usually appears as a circumscribed mass on mammographic and ultrasound examination. Poorly differentiated NECs usually present at an advanced stage, with more than 50% having lymph node metastases.

GROSS AND HISTOLOGIC FEATURES

Histologically, well-differentiated NECs (carcinoid tumors or solid-type NECs) consist of densely cellular, solid sheets or nests (alveoli) and trabeculae of cells that vary from round, plasmacytoid, spindle-shaped, and large clear cells separated by delicate fibrovascular stroma. These tumor cells form rosette-like structures and display peripheral palisading. The adjacent breast tissue may show cribriform type of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

Poorly differentiated NECs or small cell carcinomas histologically are composed of densely packed hyperchromatic small cells, with scant cytoplasm displaying an infiltrative pattern, resembling its pulmonary counterpart. An in situ small cell carcinoma component may be present involving the ducts. Areas of tumor necrosis containing pyknotic hyperchromatic nuclei may be observed along with crush artifacts and nuclear streaming.

Large cell NECs demonstrate a solid growth pattern formed by large polygonal cells, low nucleus:cytoplasm (N/C) ratios, finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, occasionally prominent nucleoli, peripheral palisading, increased mitotic activity, and necrosis. Mitotic figures can range from 18 to 35 per 10 high-power field. These

tumors exhibit neuroendocrine differentiation similar to those encountered in the lung.

tumors exhibit neuroendocrine differentiation similar to those encountered in the lung.

CYTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES OF NEUROENDOCRINE NEOPLASMS OF THE BREAST

Cytopathologic features of primary neuroendocrine tumors of the breast have been reported as individual case reports. They present features similar to those seen in their pulmonary counterparts (see Chapter 3) and will not be discussed here.

HISTOCHEMISTRY

Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the breast are argyrophilic.

IMMUNOPROFILE

Most cases are positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin, thyroid transcription factor-1, and cytokeratin-7 (CK7). Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) is expressed in majority (100%) of small cell carcinomas of the breast. Gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP-15) frequently shows strong positivity. Steroid receptors are frequently positive (estrogen receptor [ER] 80%, progesteron receptor [PR] 35%, and androgen receptors 45%).

DIAGNOSTIC DIFFICULTIES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES

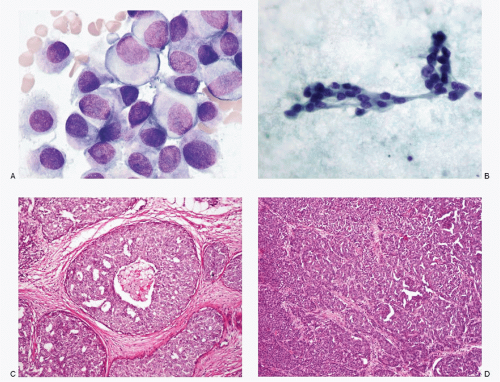

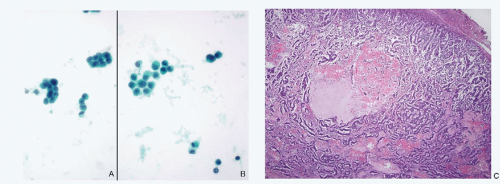

Since the incidence of primary NECs of the breast as well as its secondary involvement by NECs of extramammary site is extremely low, they are encountered very rarely in a routine cytologic practice resulting in lack of familiarity. Another reason for the limited exposure is that the diagnostic fine needle aspiration biopsies of breast lesions have been replaced by core-needle biopsies. Because of their rarity, these lesions may be easily overlooked by both surgical pathologists and cytopathologists. An example of a case of primary large cell NEC of the breast that was overlooked by the pathologist, which was subsequently diagnosed correctly by cytologic examination of pleural fluid several years later, is illustrated (Fig. 13.1).

This case highlights the need to closely observe cytologic details to identify this tumor that may otherwise appear to be invasive duct carcinoma not otherwise specified on routine histopathologic study. A high index of suspicion may help one to consider this possibility and apply appropriate immunohistochemistry for identification.

The differential diagnoses of mammary NECs include metastatic carcinoid tumors or small cell carcinomas from extramammary sites as well as lobular carcinomas and duct carcinomas of the breast with neuroendocrine differentiation. Immunohistochemistry may be helpful in distinguishing between metastatic and primary breast small cell carcinomas. Mammary small cell carcinomas are CK7 positive and CK20 negative while pulmonary small cell carcinomas are negative for both. The presence of DCIS with similar cytologic features is supportive of breast origin. Also the expression of ER and PR, and GCDFP-15, is supportive of primary breast carcinoma.

The negative immunoreactivity for E-cadherin in lobular carcinomas, in contrast to a positive reactivity in 100% of small cell carcinomas, is useful in the differential diagnosis.

Differential diagnoses should also include direct invasion of the breast by Merkel cell carcinoma, malignant lymphoma, either primary or as a manifestation of systemic disease, and malignant melanoma. Immunohistochemistry such as leukocyte common antigen (LCA) (CD45), neuroendocrine markers, CK 20, S100 protein, and HMB 45 are helpful in differentiating these lesions.

NEUROENDOCRINE NEOPLASMS IN THE LIVER

Neuroendocrine tumors are of uncommon occurrence in the liver, estimated to be in the range of 1% to 5% of all liver neoplasms. Primary hepatic well-differentiated NECs (carcinoid) as well as poorly differentiated NECs (small cell carcinomas) are exceedingly rare as very few cases are documented. Primary hepatic carcinoid tumors, encountered more frequently than the other neuroendocrine tumors, are more common in females with a mean age of 49 years. The presenting sign is usually an abdominal mass with or without associated abdominal pain. Less than 30% of cases have signs and symptoms due to excess hormone production, carcinoid syndrome being the most common. A variety of other secretory products have been described.

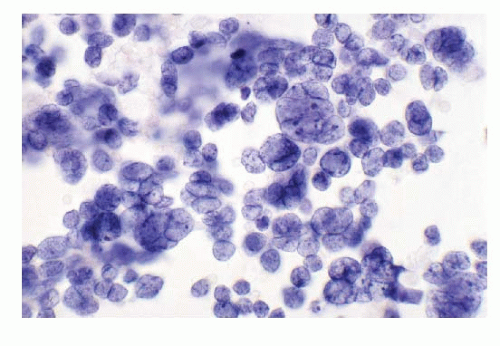

Primary poorly differentiated NECs (small cell carcinoma) of the liver are very rare and have been described. One case of small cell carcinoma in author’s experience is illustrated in Figure 13.2. A secondary lesion in the liver must be first ruled out before confirming the neoplasm as a primary neuroendocrine tumor of the liver.

Neuroendocrine Tumors of Breast (Figs. 13.1 and 13.2)

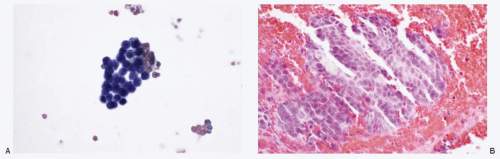

However, the liver is a common site for metastases from well-differentiated NECs that originate in the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, lungs, and biliary tract (Figs. 13.3,13.4,13.5,13.6,13.7,13.8,13.9 and 13.10). Poorly differentiated NECs arising from the lungs, uterine cervix, salivary glands, or skin (Merkel cell carcinoma) are also known to metastasize to the liver (Figs. 13.11 and 13.12). In pediatric age group, neuroblastomas frequently metastasize to the liver. Neuroendocrine tumors such as pheochromocytomas, paragangliomas, and medullary thyroid carcinomas metastasize to the liver infrequently.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Hepatic metastases of NECs may be associated with excess hormone secretions. The presenting signs and symptoms depend upon the type of hormone produced and the syndrome. In cases of nonfunctional NECs, the presenting symptoms are related to the extent of liver involvement. Owing to the slow growth, several years may lapse, from the time of resection of the primary neuroendocrine neoplasm to the occurrence of metastatic lesions.

RADIOLOGIC FINDINGS

Ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and angiography findings are sometimes useful in distinguishing carcinoids from other tumors. CT with intravenous contrast and MRI with gadolinium often show enhancement, highlighting tumor hypervascularity. Angiographic findings of an intense rapid homogeneous vascular tumor blush can be helpful in further verification. Octreotide receptor scintigraphy may be useful in identifying an extrahepatic site of disease in patients with suspected hepatic carcinoid tumors.

GROSS AND MICROSCOPIC FEATURES

Liver metastases from NECs are usually multiple and of varying sizes. In most cases, both liver lobes are affected, but miliary seedings throughout the liver are occasionally seen.

The histologic features of metastatic NECs are similar to those already described for primary lesions in several organ sites (see Chapters 3,4 and 5).

CYTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES

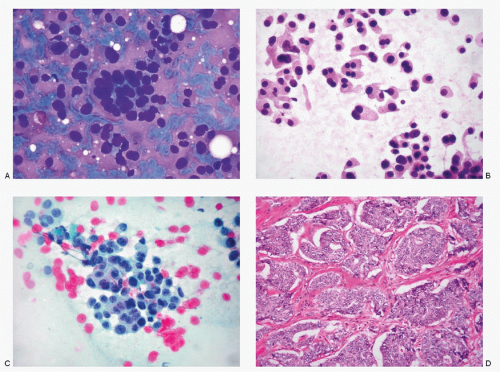

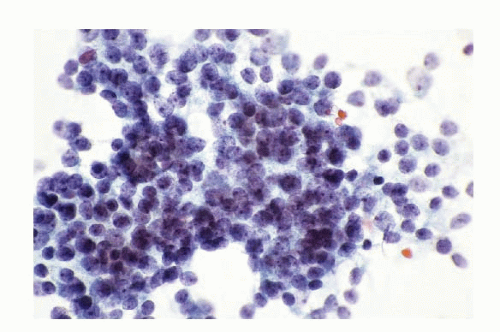

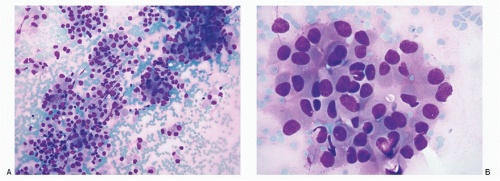

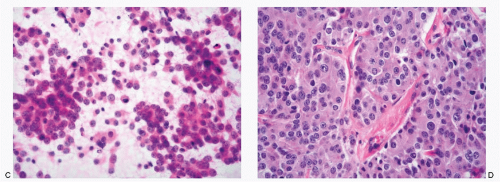

The specimens for the cytologic diagnosis of neuroendocrine neoplasms involving the liver represent the fine needle biopsies performed under radiologic guidance. The cytopathologic features of both well-differentiated and poorly differentiated NECs have already been described in detail and will not be repeated. Several examples of metastatic well-differentiated and poorly differentiated NECs are illustrated in Figs. 13.3,13.4,13.5,13.6,13.7,13.8,13.9,13.10,13.11 and 13.12. A history of primary neoplasm is extremely helpful in establishing a diagnosis. It is prudent to review the cytohistologic material of the primary neoplasm for comparison.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES

The spectrum of cytologic differential diagnoses of neuroendocrine tumors in the liver is wide because of the morphologic overlap with several non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (Table 13.1; Figs. 13.13,13.14,13.15,13.16 and 13.17). They include cholangiocarcinoma, metastatic adenocarcinomas with a small cell pattern, metastatic poorly differentiated squamous carcinoma, malignant non-Hodgkin lymphoma, plasmacytoma, metastatic malignant melanoma with small cell features, and well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma. Some of the gynecologic malignancies, especially cases of ovarian malignant tumors with small cell features, particularly granulose cell tumors metastatic to the liver, should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Metastatic neuroblastoma must be differentiated from hepatoblastoma in pediatric patients (Figs. 13.16 and 13.17).

For diagnostic confirmation of neuroendocrine neoplasia, immunostains with neuroendocrine markers and CK are necessary.

Neuroendocrine Tumors involving the Liver (Figs. 13.3,13.4,13.5,13.6,13.7,13.8,13.9,13.10,13.11 and 13.12)

Fig. 13.7: FNA Biopsy of a Liver Nodule from a Patient with a History of Bronchial Carcinoid Tumor Resected in the Recent Past. A: The direct smear of the aspirate showing a syncytial tissue fragment, consisting of uniform small round cells with poorly defined cell borders, scant cytoplasm, and high N/C ratios. There is no nuclear molding, stretch artifacts, or necrosis. B: The cell block of the aspirate confirmed metastatic carcinoid tumor (H&E).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|