With the growing use of evidence-based medicine and the increase in medical information available in both print and online sources, it has become increasingly difficult to keep up-to-date on medical advances. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are important tools for summarizing the literature and critical appraisal, providing a valuable framework for medical decision making. Beyond their role in clinical medicine, systematic reviews and meta-analyses also may be used by researchers to synthesize evidence for specific hypotheses and by policymakers to examine benefits and harms of healthcare-related interventions. Recent data suggest that at least 2,500 new systematic reviews reported in English are indexed in MEDLINE annually (

1). This chapter summarizes the key features of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, including general steps on how to undertake these methods, interpret the results, and critically appraise a published systematic review. In general, examples used will be relevant to healthcare epidemiologists, infection preventionists, and others with an interest in healthcare epidemiology and infection control.

FORMULATING THE RESEARCH QUESTION

Formulating a specific, answerable question is a critical first step when initiating a systematic review. Importance of the topic is consequential. If a research question is not worth answering, it is not worth answering

well. One recommended approach is using the acronym “PICOS” to help formulate the research question (

Table 7-1): the patient

population, the

intervention of interest, the

comparator group, the

outcome of interest, and the

study design chosen. The more precise the definition of these five components, the easier it is to apply the systematic review framework (

6).

The patient population of interest should be clearly defined in terms of age, characteristics of interest (disease or condition, such as mechanically ventilated

patients), and the setting, such as an intensive care unit (ICU). The interventions must be clearly and transparently reported. For example, for a question regarding the association between topical oral chlorhexidine and ventilator-associated pneumonia, it is important to detail the dose, frequency, method, and site of application. It is equally important to present details of the comparator under consideration, such as placebo or standard care. Definitions of standard care may differ among the primary studies in the systematic review. The outcomes of interest should also be clearly specified. For example, if ventilator-associated pneumonia is an outcome, a validated standardized definition should be used. Finally, study design considerations should be explicitly addressed. Many systematic reviews include only randomized trials, while others may choose to include both experimental and observational studies. The study question to be answered may drive the decision regarding what types of studies are to be included. Whatever the rationale may be, decisions regarding the population, intervention, comparison group, outcome, and study design should be clearly stated in the systematic review or meta-analysis.

DEVELOPING CRITERIA FOR INCLUDING STUDIES

A key component of a systematic review is the prespecification of criteria—the eligibility criteria—for including and excluding studies in the review (

4). The patient population, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes laid out in the research question are used to derive the eligibility criteria. For the patient population, the definition should be sufficiently broad to avoid unnecessary exclusion of studies but should be narrow enough that a meaningful result is expected when they are considered in aggregate. Depending upon the condition of interest, the study population may be defined in the context of other characteristics such as sex, race, age, educational status, or venue of care (e.g., ICU, nursing home). Any restrictions with regard to population characteristics should be explicitly defined and the rationale provided.

Table 7-2 provides a list of relevant questions to be addressed when evaluating the study subjects.

The intervention should also be described in detail. For those reviews in which there are slight variations in the intervention across studies, a table describing the elements of each intervention is helpful. Important considerations include decisions regarding trials with multiple interventions. The arms of the trial should be clearly stated and the comparison groups specified. This is of particular importance when the results will be pooled for meta-analysis. For example, the pooling of relative risks for septicemia that compare an intervention with usual care should be separate from the pooling of such relative risks when comparing an intervention with a placebo. Relevant questions regarding the intervention are listed in

Table 7-3.

A clinically useful review will address clinically relevant outcomes. The outcomes for each study should be examined to determine the extent to which they are common across all studies. A decision is often necessary regarding handling of studies that have composite outcomes. For example, if the desired outcome is catheter-related bloodstream infection, should a study that fails to distinguish between catheter colonization and catheter-related bloodstream infection be included? Measurement of the outcome is also an important consideration, both in terms of the scale and timing. For example, if ventilator-associated pneumonia is an outcome, it would be important to take into account the variability in definitions used by investigators. Some studies may use a combination of clinical, radiographic, and lower respiratory tract sampling, while others may choose to use clinical and radiographic data alone or in combination with a sputum or tracheal aspirate specimen. In general, surrogate outcomes should be included with caution, because they may not always predict clinical outcomes accurately.

Table 7-4 lists several outcome-related questions to be evaluated when conducting a systematic review.

The types of studies to be included in the review should be specified

a priori. Most systematic reviews address evidence produced from randomized controlled trials. Randomized controlled trials are less likely to have selection bias, because proper randomization should prevent systematic differences between baseline characteristics of participants. Randomization of large groups of patients tends to equalize the distributions of subjects for both known and unknown potential confounders; such trials provide the best evidence of an unbiased treatment effect. Therefore, a systematic review of randomized trials has a distinct advantage. Even within randomized trials, however, there may be considerations related to study design such as whether cluster-randomized trials or crossover trials should be included (

4). Importantly, there are some research questions in which a trial is not ethical or feasible. In these instances, a review of observational studies may be appropriate. Although estimates of treatment effectiveness obtained from observational studies—rather than randomized trials—are more likely to suffer from internal bias, the results may be more generalizable to broad patient populations due to the restrictive eligibility criteria usually inherent within randomized controlled trials.

The scope of the research question—either broad or narrow—is important at the outset. For example, a metaanalysis that targets whether topical oral chlorhexidine can prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia is narrower in scope than a meta-analysis that seeks to answer if oral decontamination (antibiotics and antiseptics) can reduce the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Factors that should be considered when defining the scope of a review originate with underpinnings of the problem at hand, whether purely clinical, biological, and/or epidemiological. Extremely broad questions—for example, what is the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnostic approach, treatment, and preventive options for ventilator-associated pneumonia—are often best addressed through a traditional narrative review.

Finally, a research question may need to be revisited over time. As evidence accumulates regarding a particular clinically relevant topic, it is important to update systematic reviews and meta-analyses with the results from the newly published studies. Therefore, systematic reviews are always time dependent and are most useful in clinical medicine when they contain all the most relevant literature available.

LITERATURE SEARCH

Systematic reviews require a comprehensive, objective, and reproducible search of multiple sources to ensure that all relevant studies are included. Healthcare bibliographic databases such as MEDLINE are a good place to start, although MEDLINE alone is not considered sufficient and should be supplemented with additional data sources. Currently, 5,200 journals in 37 languages are indexed in MEDLINE, and fortunately, PubMed provides free online access to MEDLINE. EMBASE is another electronically searchable database that is available only by subscription and has over 12 million records since 1974. While there is some overlap between EMBASE and MEDLINE, of the 4800 journals indexed in EMBASE, 1,800 are not indexed in MEDLINE, and of the 5,200 indexed in MEDLINE, 1,800 are

not indexed in EMBASE. Access to MEDLINE via PubMed is located at www.pubmed.gov and for EMBASE at www.info.embase.com.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) is an excellent source of reports of controlled clinical trials. CENTRAL, published as part of the Cochrane Library, is updated quarterly. Although many of the records in CENTRAL overlap with MEDLINE or EMBASE, CENTRAL includes reports of clinical trials that are not part of MEDLINE or EMBASE, which may have been published only in specialized registers and other resources. If other reviews are of interest, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination is an excellent resource (http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/).

Besides these key international databases, there are several national and regional databases that are useful to examine for additional studies. Many are available free of charge on the Internet.

Table 7-5 lists examples of regional electronic databases (

4).

When designing the search strategy, important considerations include whether the review is limited to randomized trials, whether the language of the publications will be inclusive or restrictive, the time period of the literature search, and whether data from unpublished studies are to be included. Assistance from an experienced healthcare librarian is highly recommended.

A balance between sensitivity and precision may need to be struck when undertaking searches to identify potentially relevant articles. Sensitivity is defined as the number of relevant reports identified divided by the total number of relevant reports in existence. Precision is defined as the number of relevant reports identified divided by the total number of reports identified. Article abstracts identified through a literature search can be quickly scanned for relevance to the research question; sensitivity is usually preferred over precision to ensure that the systematic review includes all potentially relevant articles.

In general, electronic databases can be searched using standardized subject terms assigned by indexers (MeSH for MEDLINE). The goal of the standardized subject terms is to ensure that articles using different words to describe the same concept are easy to retrieve. However, often the subject terms may not retrieve articles corresponding to the terms of interest. An additional challenge is that standardized subject terms may differ from one electronic database to the other; thus, a search must be customized to each database being searched.

The

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews recommends that one way to identify controlled vocabulary terms for a database is to retrieve articles that meet the inclusion criteria and to note which subject terms have been applied to them. Those subject terms can then be put into the search to identify additional relevant articles. The “Explode” feature in MEDLINE searches narrower terms that are “under” the searched term in the MeSH hierarchy. The “Explode” feature in MeSH does not search related terms. For instance, using Explode with the MeSH term “Hepatitis” will find all articles indexed with more specific terms beneath it as well as general articles that are indexed simply, “Hepatitis.” In MEDLINE, it is important to note that a report of a randomized controlled trial would be indexed as “Randomized controlled trial” while an article about randomized controlled trials would be indexed with the term “RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS AS TOPIC.” A comprehensive search strategy often includes, in addition to subject terms, a wide range of free-text terms such as pressure sore OR decubitus ulcer. Boolean operator terms such as “AND,” “OR,” and “NOT” are applied in searches to refine the search strategy by joining each search concept to the next.

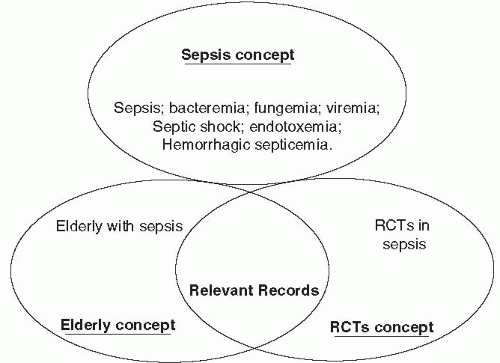

Figure 7-1 provides an example of combining search concepts to identify relevant records (

4).

As most systematic reviews focus on randomized controlled trials, it is instructive to become familiar with a highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE. There are two versions: a sensitivity-maximizing version and a sensitivity- and precision-maximizing

version. These were developed by the Cochrane Collaboration and are shown in

Tables 7-6 and

7-7.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access