Median Sternotomy and Thymectomy

M. Victoria Gerken

Phillip C. Camp

Steps in Procedure

Mark the midline of the skin and create incision from sternal notch to 1 to 2 cm below xiphoid

Divide connective tissue to sternum

Verify midline of sternum and score the periosteum

Divide abdominal fascia for several centimeters

Gently dissect under sternum at both ends

Use sternal saw to divide the sternum

Obtain hemostasis on cut bone and place sternal retractor

Thymectomy

Resection of all fatty tissue is essential

Begin inferior and elevate lobes of thymus and associated fat from pericardium

Take dissection to phrenic nerve on each side if edge of thymus is not well-defined

At cephalad aspect, control venous branches to brachiocephalic vein with clips or ligatures

Trace lobes into neck, where they become fibrous bands

Divide and ligate termination

Attain hemostasis

Place chest tubes or closed suction drain as appropriate

Close sternum with multiple interrupted sternal wires

Reapproximate abdominal fascia

Close incision in layers

Hallmark Anatomic Complications

Injury to brachiocephalic vein

Injury to phrenic nerves during thymectomy

Sternal dehiscence or infection

Injury to internal thoracic (mammary) arteries during sternal closure

List of Structures

Sternum

Gladiolus (body)

Manubrium

Xiphoid process

Angle of Louis

Interclavicular ligament

Sternocleidomastoid muscle

Pectoralis major muscle

Aponeuroses of internal and external oblique muscles

Brachiocephalic (innominate) artery

Left and right brachiocephalic (innominate) veins

Internal thoracic (mammary) arteries

Pericardium

Pleura

Thymus

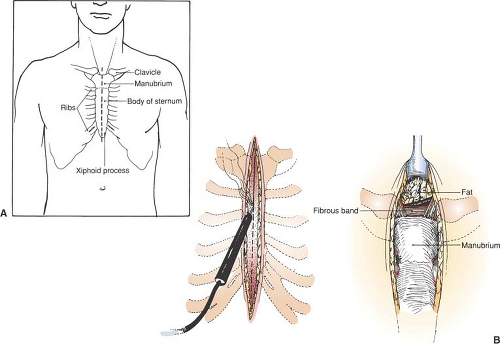

Median Sternotomy

Median sternotomy allows rapid, excellent exposure to the anterior or middle mediastinum and is ideal for cardiac, thymic, and bilateral pleural procedures. Bilateral pulmonary resections, such as bullae or metastases, can be performed; however, it can be difficult to perform a formal lobectomy through this incision. Sternotomy, including partial or upper sternotomy, can allow for thymectomy and provides access to the trachea to the level of the carina. As an extension of a cervical incision, a partial or complete sternotomy can provide adequate exposure for resection of an enlarged substernal goiter. Only limited exposure of the posterior mediastinum (esophagus and descending aorta) is obtained. The sternum is generally stable on closure, and dehiscence of this incision occurs only rarely. It also offers the distinct advantage of being less painful than the standard posterolateral thoracotomy and is very well tolerated in all age groups. Respiratory status is only minimally impaired after this approach.

Incision (Fig. 21.1)

Technical Points

Mark the midline of the skin before incising, ensuring that the skin incision is in the midline. Extend it from the sternal notch to a point roughly 1 to 2 cm below the tip of the xiphoid. Using electrocautery, divide the connective tissue until the sternum is reached. Occasionally, there is a thin layer of decussating pectoral muscle in the midline over the sternum. Divide this and score the external periosteum of the sternum with electrocautery. Carefully palpate the lateral edges of the sternum with the thumb and index finger of your nondominant hand so that the incision can be kept directly in the midline. At the angle of Louis (sternomanubrial junction), use a snap or forceps to identify the lateral margins of the sternum. This is advised because the pectoralis muscles do not universally delineate the center of the sternum. Straying off the midline will later cause the sternal retractor to “kick up” on the thinner side and can adversely affect healing of the sternal bone.

Score the periosteum caudally to the tip of the xiphoid. Divide the abdominal fascia in the midline for a short distance, taking care not to enter the peritoneum. Superiorly, score the periosteum to the sternal notch and carefully feel for a tough ligamentous structure on the posterior aspect of the notch. Divide this ligament with great care using cautery. (The electric sternal saw frequently will jam or bog down on tissue of this type.) Introduce your index fingers under the sternum from both the sternal notch and the xiphoid. Gentle dissection here will facilitate detachment of the underlying structures from the back of the sternum before the sternum is divided. Ask the anesthesiologist to deflate the lungs fully to allow the pleura to fall posteriorly as much as possible. Bisect the sternum with the sternal saw starting from either end. Pull gently up and forward with the saw during this maneuver, again to reduce the risk for injury to underlying structures. Obtain hemostasis by cauterizing the periosteum along the lower edge of the sternum. Because the soft tissue will slightly retract after sternal division, be sure to cauterize several millimeters back along the undersurface of the cut sternum. The divided edge of the sternum often oozes from the marrow. Application of a paste containing thrombin, Gelfoam, or a similar material will promote hemostasis and keep your field clean.

Place folded green towels along the divided edges of the sternum and insert the sternal retractor. When you place the sternal spreader, remember that the more cephalad the retractor is placed, the greater the risk for injury to the brachial plexus.

In the situation of a tight or limited exposure, modest additional division of the midline abdominal fascia (extraperitoneal) may be beneficial.

In the situation of a tight or limited exposure, modest additional division of the midline abdominal fascia (extraperitoneal) may be beneficial.

Anatomic Points

A median sternotomy incision exactly in the midline should not sever any muscle fibers anterior to the sternum. Should the incision stray from the midline, however, it is possible to divide some fibers of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (originating from the manubrium), the pectoralis major muscle (originating from the manubrium and body), and the aponeuroses (linea alba) of the internal and external oblique muscles (attached to the xiphoid process). A true midline division of the sternum likewise should not involve any muscle fibers attached to the deep surface of the sternum. However, slightly lateral to the midline, the sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles originate from the manubrium, and the slips of the transversus thoracis originate from the body. Frequently, slips of the diaphragm originate from the sides of the xiphoid process.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree