Introduction

Regardless of their experience or rank within the organization, the task of synergizing individual talents into a larger group effort is often problematic for new healthcare manages. Building a team can be a complex task. Trying to establish common goals, objectives, and shared dedication to a mission is one thing—managing and harnessing the abilities and talents of a diverse group of individuals so as to move toward a mutual goal is another thing altogether. If you examine the overall structure of your healthcare organization, you will probably find it consisting of many solid teams. Some departments may be stronger than others—perhaps their members have stronger talents or maybe they work together more smoothly and efficiently. If the department is considered to be a stellar team, it probably has both these elements of talent and group cohesion. As a newly appointed healthcare manager, you can establish a strong team orientation with these resonant and resilient components.

This chapter will discuss ways of analyzing a team and determining the potential contribution of each member to the team effort. After analyzing the work personality as it relates to health care, the chapter will close with a detailed discussion on establishing and then reinforcing a value-driven team orientation. Upon reviewing these concepts and considering their potential application to your situation, you should be closer to establishing a cooperative, progressive work group.

As you progress through this chapter, think of individuals in your department and assess what you have observed about each one to the evaluation material presented throughout this chapter. Keep in mind your team’s mission and objectives and what you perceive to be key potential obstacles to developing a strong team so that the material herein becomes realistic, effective, and more practical in your own situation.

Conducting a Team Analysis

Great teams consist of great players. To build a team, you must first analyze the relative strengths and weaknesses of individual players, both current and prospective. This section discusses methods of analyzing strengths and weaknesses of individual members and developing a system to assess the potential, performance, and contribution of each one. To begin with, you will need a leader’s notebook. In this one, make entries about your evaluation of each member (try to be as objective as possible). Use the six basic sources described in the following subsections to compile your analysis.

Performance reviews and documentation include the evaluations completed by your management predecessor. Remember that under the best of conditions performance evaluation is a subjective exercise; personal bias on the part of your predecessor might have entered into the equation. While reviewing individual employee files, make copious notes about perceived strengths and weaknesses and the employee’s development needs. Note in particular any comments on the employee’s ability to work with others and his or her contribution to the team effort. Try to gauge employee attitude and interpersonal skills.

Write down your firsthand observation of each employee’s progress. If your new employees are former peers, you already may have opinions about their performance level and ability to work as part of a team. Remember that this logbook is a compilation of your own subjective notes; it is not a legal document or anything that can be used against you in any manner, so be forthright in your note taking.

As mentioned in earlier chapters, upon assuming your responsibilities as department manager, interview each employee regarding their goals and objectives, aspirations, and opinions on how to improve performance on an individual and departmental basis. Only ask questions that relate specifically to your particular department’s activity, current team orientation, and established group processes. These answers can be most telling in terms of individual attitude toward team cohesion and group contribution.

Seek out any useful information uncovered during the actual hiring process for applicants screened by you or by your predecessor. In most healthcare organizations, the human resource department has copies of interview score sheets or similar data that will give insight into the employee’s attitude, people skills, and team orientation. Most of these professionals are very skilled at extrapolating data obtained in the selection process which can be quite helpful in assessing potential team orientation. In conducting applicant interviews, additionally, always ask about teamwork experience and how highly group interaction is valued.

Some healthcare institutions designate the initial 3 months of employment as a probation period. This means that a new employee’s performance is closely monitored and assessed for a period of the first 90 days in a given job. More often than not, copious notes are taken by the reviewing manager and other individuals in the chain of command. Probation notes are a great means of determining the employees’ team orientation, individual strengths and weaknesses, and a wealth of other information essential to determining potential value to the work group.

Several other resources can help evaluate individual performance relative to team contribution. Certainly the job description, combined with your perception of the individual’s ability to meet the performance standards delineated in the job description, is important. It is vital to examine how each employee performs the job, conducts herself or himself in the workplace, and acts as a source of information and supportive player. Furthermore, it is vital to examine individual potential and promotability in terms of technical acumen. (Technical acumen would include how much a compensation specialist knows about the hospital’s employee benefit program or how much a pharmacist knows about decongestants.) A simple standard to apply in this case is determining what the individual’s present level of expertise is, and how vigorously he or she pursues new technical knowledge and business acumen.

Finally, perhaps the most telling resource of determining caliber of team orientation is simply to observe collective departmental behavior. The following 5 questions can go a long way toward determining an individual’s team potential:

Toward whom do people seem to gravitate in times of crisis?

Which individuals seem to be most willing to share technical knowledge?

Which individuals become actively involved in orienting new members to them?

Which individuals seem to work consistently in isolation?

Which individuals seem to provide leadership to the team by virtue of example, communication, and inspiration?

The answer to these questions, combined with the information from all of the sources mentioned throughout this section can go far in giving you a general perspective of your team leaders and followers. They can also give you an idea of who the more reluctant team players might be and whom you might target for specific individual team involvement.

Qualities of a Strong Team Player

As you conduct your team analysis, several characteristics and work-related behaviors should be identified and quantified. This section will review several of these qualities and provide guidelines for identifying them, and a profile will be presented that you can incorporate into your efforts for the selection of new staff members.

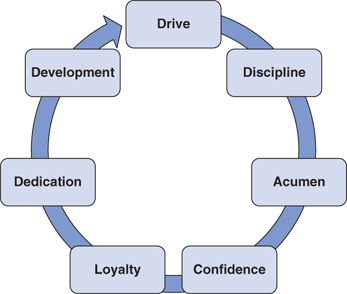

The composite in Figure 7–1 provides some insight into what qualities a strong healthcare team member might possess. The model can serve as a building block in formulating a team blueprint.

Each team member must have a certain amount of drive to attain individual and group goals. He or she does not need to be jump-started every morning or at the beginning of each shift. The drive toward performing strongly, learning and growing every day, being a motivator for others purely by example, expending energy, and applying on-the-job initiative all characterize a stellar team player.

Good teams are disciplined. They steadily make exact determinations and seek all facts necessary to making a decision. They get the job done correctly the first time and do not cause little problems that can add up to big problems. Good teams know intrinsically what has to be done and how to do it; that is, they set their own objectives and determine a course of action for achieving those objectives with excellence. Their sense of discipline is self-perpetuating throughout the entire department.

One thing that makes the healthcare field so unique is the combination of many technical talents synergized into one greater whole. Every employee on the payroll of a healthcare organization has a certain amount of technical acumen and expertise that they bring to the job every day. Whether that expertise lies in conducting a good laboratory assay, filling a prescription correctly, or cleaning a patient’s room quickly and efficiently, strong team members bring their unique, essential ability to the workplace every day. Never taking a know-it-all attitude, a strong team player looks at every day as an opportunity to learn something new.

Every team member should feel self-assured about his or her technical ability and the resilience to perform under changing and critical circumstances. A strong player usually radiates confidence about departmental goals and everyday work activities. Both customers/patients and fellow workers pick up on this attitude and therefore feel comforted by this individual’s presence. They have the conviction that the job will get done and that when the going gets tough—an everyday occurrence in health care—the job will still get done.

Team loyalty is critical in health care, and each player’s loyalty cannot be selective or sporadic in its application. The first loyalty, of course, is to the healthcare institution and its mission of providing care to its patient community. The second loyalty is to the department manager/team leader and is demonstrated by following set objectives, providing feedback, and accomplishing team goals. The third loyalty is to the work group, to act as a positive participant who contributes to group goals. Finally, the individual maintains a dedication to always escalating their individual strong performance and progressive development on the job.

Strong team members emanate dedication to a common goal of providing stellar health care to all customers/patients. They are equally dedicated to all team goals, departmental objectives, and one another in providing help, guidance, and technical assistance. They are passionate in their allegiance to the healthcare profession and equally dedicated to providing whatever support is needed to meet the healthcare mandate of premium service delivery.

Each team member should desire to grow and develop on the job. This development, however, expands itself beyond the parameters of basic technical growth. Strong healthcare team members seek to learn more about the healthcare business and to understand the changing dimensions of the business. They know how to interpret the impact of change in the social environment and in their communities, and they understand how these changes may affect their particular duties and the institution’s mission.

An often-overlooked aspect of team member development is interpersonal skills. A strong team member seeks to learn more about individual personalities and the proclivities of fellow team members and what their professional preferences and personal likes and dislikes might be relative to performance. This focus on development of interpersonal skills contributes significantly to an ever-expanding knowledge base from which the employee can grow, prosper, and continuously improve the quantity and quality of the work contribution.

Analyzing Work Personality

In industrial psychology and management philosophy circles, much discussion surrounds a concept known as work personality. The work personality of a healthcare employee is basically defined as how a job is performed, as opposed to what is done. As public scrutiny and customer/patient perception healthcare delivery become more intense and more keenly focused, the attributes of work personality relative to healthcare employees become increasingly more important.

In conducting a team analysis, you may find it useful to identify the attributes of work personality present in your team, as well as to study their effect on team performance. This effort can help deal with employees who go to extremes in performing their jobs, thus creating performance problems for the team. For example, an employee performing his or her job in an extreme manner is a strong performer who becomes a workaholic and pressures coworkers to work to his or her unrealistic standard. Several strategies and systems aid in analyzing work personality of healthcare employees. One of the most widely used work personality profile systems is the Quantitative-Communological Organizational Profile System (the Quan-Com System) used by more than 150 hospitals. The Quan-Com System has been endorsed by several major healthcare accreditation organizations. This system may be useful for studying your team orientation and work behavior. Using this in turn can help you more accurately determine the team development needs of your staff and the individual tendencies and liabilities of your team members.

The basic elements of this system are attitude orientation, people skills, managerial aptitude, and team orientation. As they relate to the analysis of potential interactions and performance within your department, once again it is valuable to write in your notebook behavior and actions that might indicate a prospective member’s propensity for constructive or nonconstructive behavior in any of the four areas, which are described in the following sections and subsections.

First, review each employee relative to a series of attitude orientation characteristics. These characteristics include adaptability, accountability, perseverance, and work ethic.

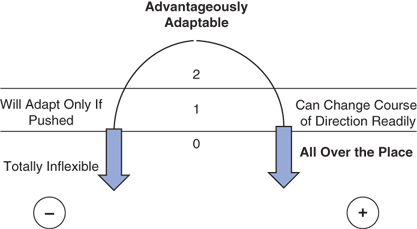

Individuals lacking on-the-job adaptability are inflexible, reluctant to learn new methods or adapt to new ideas, and have difficulty relating to varied personalities. On the other hand, one who is too adaptable is said to be wishy-washy, unwilling to take a stand, or changes with any minor fluctuation in the work environment.

Individuals who demonstrate adaptability in good balance can adjust well to new methods and ideas with excellent practical results. They also are flexible in dealing with a wide range of people, reacting proactively and positively to change, and developing not only a Plan A, but also a Plan B in accomplishing set objectives. In essence, these individuals are versatile and can accommodate change positively, function well in crisis, and set new goals readily as circumstances dictate. This behavior is illustrated on the adaptability bell curve shown in Figure 7–2. You can draw similar bell curves for other attitude orientation factors to chart pluses and minuses. Write the initials of team members who represent points along the curve relative to their behavior.

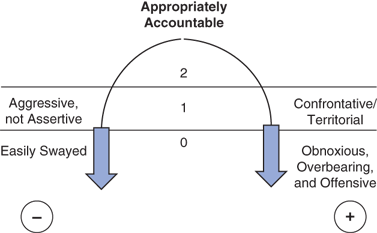

Another attitude orientation factor is accountability. Individuals who demonstrate this characteristic are able to make a stand and stay with their objective without wavering in their position. These individuals take command appropriately in all business situations, and they are enterprising, direct, and persuasive in their business dealings.

Individuals whose behavior falls along the minus range of the curve (see Figure 7–3) usually will not take a stand on major issues and are overlooked by managers. At the other plus extreme are those who are too aggressive or pushy and may be characterized as obnoxious, overbearing, or offensive. They alienate fellow team members and over time become isolated or, worse, create the unneeded difficult situations.

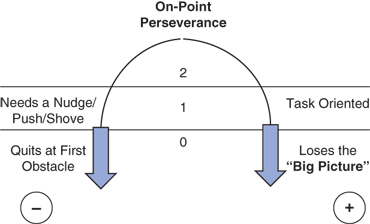

The third attitude orientation factor is perseverance. Perseverant workers are consistently persistent and tenacious in accomplishing a goal (stick-to-itiveness). They forge ahead tirelessly to a successful end despite situational obstacles. These players tenaciously assist fellow team members in the pursuit of group objectives (Figure 7–4).

Individuals who lack perseverance will quit at the first detour and usually bring someone down with them. That is to say, their malaise and resistance toward accomplishing a goal can act as a negative contagion and affect the morale and motivation of other team members.

Too much perseverance leads to tunnel vision; that is, these players are task oriented at the expense of being mission oriented (can’t find the forest through the trees or lose the mission at the expense of the effort).

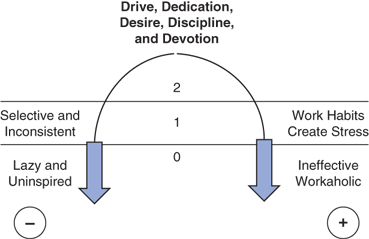

Work ethic is encompassed in some of the work personality factors already discussed. For example, the work ethic is fueled by drive and dedication on the part of healthcare workers who stick to a job until it is done and have a basic industriousness (Figure 7–5). Team members lacking this quality eventually will be identified by fellow workers as unreliable and excluded from the team equation. On the other hand, too much of a work ethic can define a workaholic, an unfortunately common figure in the high-stress healthcare arena.

The second category of the Quan-Com System for examining work personality is people skills. These skills fall into three general areas: communication, perceptiveness, and presence and bearing.

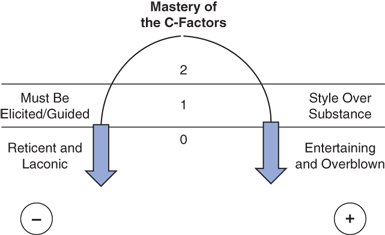

You may find it useful to analyze the communication abilities of all individuals in your department, including the ability to deliver a message clearly and with comprehension. Similarly, you may want to analyze members’ various energy levels (Figure 7–6). High-energy individuals are enthusiastic, enthralled by their work, convey a sense of electricity in their encouragement to others, and are eager to take on all new responsibilities and new challenges.

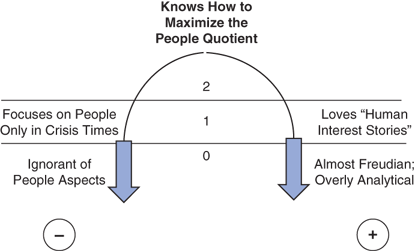

Perceptiveness relates to the insight individuals possess in dealing with others. Perceptive workers understand the people equation as it relates to the healthcare team process. Those lacking in this quality focus on people only after a problem surfaces, as they tend to be oblivious to the people aspect (Figure 7–7). At the other extreme are overly perceptive individuals, who focus on personalities and interpersonal problems at the expense of programs, processes, products, and objectives.

In weighing the concept of presence and bearing, simply ask yourself “What would I think of this individual if he or she was the first person I came in contact with upon coming to the hospital?” The answer will tell you what customers/patients and fellow workers perceive about this particular team member (Figure 7–8). Presence and bearing—overall demeanor—denote the positive or negative impression created in a business situation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree