Mastectomy: Total (Simple), Modified, and Classic Radical

Total (sometimes called simple) mastectomy removes all the glandular tissue of the breast. It is sometimes required for treatment of extensive ductal carcinoma in situ. In combination with reconstructive surgery, bilateral total mastectomy is sometimes used for breast cancer prophylaxis in carefully selected patients.

Modified radical mastectomy adds the removal of the node-bearing tissue of the axilla while preserving the muscular contours of the upper chest wall. The operation was modified from the original or classic radical mastectomy to enhance the cosmetic result without compromising control of disease. Many modifications of the original classic radical mastectomy have been described. They differ in the extent of tissue removed and the completeness of axillary dissection. The modification described here combines a thorough axillary dissection with preservation of muscle contour. Other modified radical mastectomy techniques are detailed in the references.

Classic radical mastectomy is still used in those rare circumstances in which wider excision of the pectoral muscles might enhance local control. This is increasingly rare as better neoadjuvant chemotherapy has become available.

When mastectomy is performed for risk reduction (sometimes termed cancer prophylaxis) or for early disease, skin-sparing mastectomy with immediate reconstruction may be appropriate. Techniques applicable to that operation are mentioned throughout and references at the end give greater details on this evolving procedure. The procedure is also briefly discussed in Chapter 15.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (see Chapter 18) is frequently combined with mastectomy. It may be performed through the lateral aspect of the incision or, if a skin-sparing technique is employed, through a separate axillary incision.

Steps in Procedure

Total Mastectomy

Position patient with arm out; may drape arm free if desired

Ellipse of skin including nipple-areolar complex and skin over tumor

Develop flaps at level of fusion plane between subcutaneous fat and fatty envelop of breast to sternum medially, clavicle superiorly, rectus inferiorly, latissimus laterally

Elevate breast from pectoralis major muscle from superior medial to inferior lateral

Take pectoral fascia for cancer

Leave pectoral fascia for immediate reconstruction with implant

Identify and ligate perforating branches of internal thoracic (mammary) vessels

Obtain hemostasis and close wound over two closed suction drains

Modified Radical Mastectomy

Develop flaps and dissect breast from pectoralis major muscle as described above

Leave breast attached at lateral aspect and use weight of breast to enhance retraction

Incise pectoral fascia at lateral edge of pectoralis major and elevate muscle

Dissect under pectoralis major muscle, removing all fatty node-bearing tissue

Preserve median pectoral nerve

Sweep fatty tissue laterally and expose and protect long thoracic nerve

Identify axillary vein and sweep fatty tissue downward

Ligate and divide thoracodorsal vein and preserve thoracodorsal nerve and artery

Sweep all fatty tissue downward and terminate dissection

Obtain hemostasis and lymph stasis and close over two closed suction drains

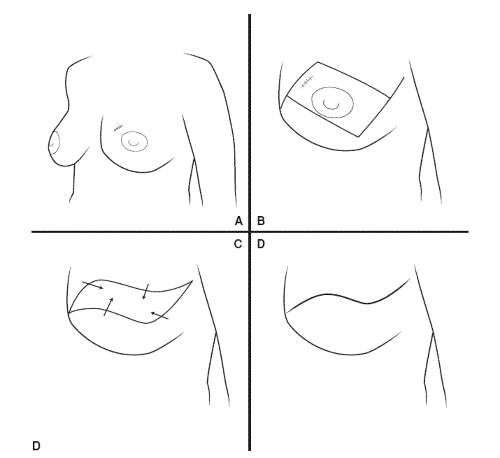

Dog Ear Correction by V-Y Flap Advancement

Close middle of incision

Elevate apex of dog ears to define pyramids of tissue

Excise triangles of redundant tissue

Suture the resulting reverse arrowheads in place

Record length of dog ear in operating note

Classical Radical Mastectomy

Position patient as noted, prep abdomen or thigh for possible skin graft

Develop flaps as previously outlined

Shave pectoralis major muscle (with overlying breast tissue) over chest wall from medial to lateral

Ligate perforating branches of internal thoracic (mammary) vessels as encountered

Similarly excise pectoralis minor muscle when exposed

Axillary dissection proceeds as previously outlined but includes level III nodes

Close as previously described, placing skin graft in midportion if required

Hallmark Anatomic Complications

Injury to long thoracic nerve

Injury to thoracodorsal nerve

Injury to intercostobrachial nerves

Injury to axillary vein

Seroma formation

List of Structures

Pectoralis major muscle

Pectoralis minor muscle

Subclavius muscle

Clavipectoral fascia

Coracoid process

Lateral pectoral nerve

Medial pectoral nerve

Thoracodorsal nerve

Long thoracic nerve

Axillary artery

Axillary vein

Thoracoacromial artery

Thoracodorsal vein

Internal thoracic (mammary) artery

Internal thoracic (mammary) vein

Axillary lymph nodes

Landmarks

Clavicle

Anterior rectus sheath

Latissimus dorsi muscle

Sternum

Total and Modified Radical Mastectomy

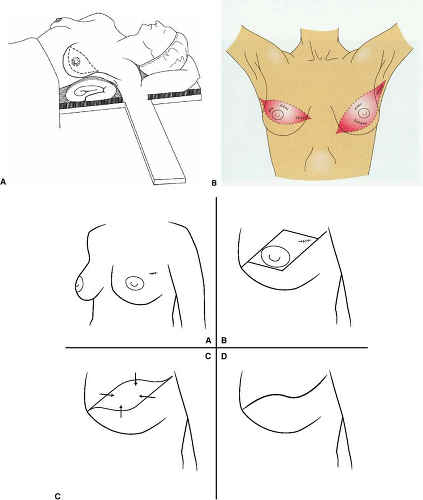

Position of the Patient and Choice of Skin Incision (Fig. 17.1)

Technical and Anatomic Points

The operation is performed under general anesthesia. After the initial intubation, muscle relaxants are avoided so that nerve function can be assessed. Position the patient supine, with the ipsilateral arm extended on an armboard. If necessary, place a small, folded sheet under the shoulder, to improve exposure. Avoid hyperextending the shoulder because this can cause neurapraxia. Drape the arm free so that it can be moved during the course of the dissection (Fig. 17.1A).

The choice of incision depends on several factors, including the location of the lesion, any prior biopsy incisions, and planned reconstruction. When immediate reconstruction is to be performed, design the skin incision in consultation with the plastic surgeon who will scrub in to do the reconstruction. In many cases, skin-sparing flaps can be created in such a manner as to be oncologically correct and yet provide an aesthetically pleasing outcome.

When delayed reconstruction is a possibility, a generally transverse incision is favored as it facilitates reconstruction. When reconstruction will not be performed, a generally oblique incision that is high at the axillary end and low medially provides excellent access. Flaps generally heal very well with this incision and the end result is a flat scar to which prostheses can easily be adapted.

The skin incision should include the nipple-areolar complex and the skin overlying the tumor, biopsy cavity, and any prior biopsy incision (Fig. 17.1B). The biopsy cavity is considered to be contaminated by tumor cells and frequently contains gross residual disease. It must be excised in its entirety as dissection progresses. Therefore, if the biopsy is performed through an incision located at some distance from the mass, a correspondingly larger amount of skin should be sacrificed. Alternatively, an ellipse of skin around the biopsy incision may be excised

separately. Do not compromise the skin incision because of fear of difficulty in closure. A skin graft will heal well over the underlying muscle and may be used if necessary. This is rarely necessary if flaps are designed properly.

separately. Do not compromise the skin incision because of fear of difficulty in closure. A skin graft will heal well over the underlying muscle and may be used if necessary. This is rarely necessary if flaps are designed properly.

Figures 17.1C and 17.1D show how a “lazy S” type incision provides flaps that can accommodate a variety of lesion locations, yet slide together to afford primary closure with minimal tension. The easiest way to create the lazy S is to first outline a diamond shape around the nipple areola and tumor location, then round the corners a bit. As the incision is closed, flaps are allowed to slide from side to side and from top to bottom as shown. The result is a flat scar that is hidden under clothing, even for some upper inner quadrant lesions.

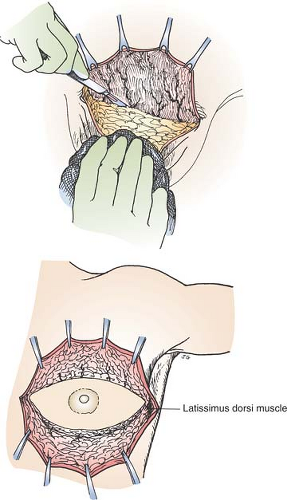

Development of Flaps (Fig. 17.2)

Technical Points

Incise the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Visualize the breast as lying encapsulated in a separate layer of subcutaneous fat that lies 0.5 to 1.0 cm below the skin. Often, this layer can be defined as the skin incision is made. Place Lahey clamps on the dermal side of the upper flap and have an assistant place these under strong upward traction (Fig. 17.2A). Apply countertraction by pulling the breast tissue down and toward you strongly with a lap sponge. Avoid manipulating the breast overlying the biopsy site. Develop flaps by sharp dissection using a shaving motion with a sharp knife or electrocautery. If a knife is used, change blades frequently. Dissection in the proper plane is surprisingly bloodless. A network of large subcutaneous veins is often visible on the underside of the flap and will be preserved if dissection progresses in the proper plane. Ligate occasional bleeders on the underside of the flap. (Use electrocautery with caution on the flap because it can burn through the thin flap to damage the overlying skin surface.) Confirm the thickness of the flap by palpation as the dissection progresses.

An alternative technique uses slightly opened Mayo scissors to develop the flaps by a push-cut technique. This is particularly useful when the skin incision is small, as during skin-sparing mastectomy.

In the axilla, the skin flap will be crossed by hair follicles and apocrine glands. Divide these sharply. Raise flaps to the level of the clavicle superiorly, the midline medially, the anterior rectus sheath inferiorly, and the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi muscle laterally (Fig. 17.2B). Of these, the lateral border of the latissimus dorsi is generally the most difficult to find.

Identify this muscle by palpation of a longitudinal ridge of muscle tissue. Dissect sharply down to confirm its identity by visualizing longitudinal muscle fibers. Trace the muscle up toward the axilla. Check the upper flap for hemostasis and place a moist laparotomy pad under the flap. Place Lahey clamps on the inferior skin incision and develop the inferior flap by the same technique. The plane between breast and subcutaneous tissue is frequently less well defined inferiorly, and unless care is taken, the inferior flap may be cut too thick. Guard against this by constant palpation of the thickness of the flap. If white fibrous tissue (breast or suspensory ligaments of the breast [Cooper’s ligaments]) is seen, the flap is too thick and must be cut thinner.

Identify this muscle by palpation of a longitudinal ridge of muscle tissue. Dissect sharply down to confirm its identity by visualizing longitudinal muscle fibers. Trace the muscle up toward the axilla. Check the upper flap for hemostasis and place a moist laparotomy pad under the flap. Place Lahey clamps on the inferior skin incision and develop the inferior flap by the same technique. The plane between breast and subcutaneous tissue is frequently less well defined inferiorly, and unless care is taken, the inferior flap may be cut too thick. Guard against this by constant palpation of the thickness of the flap. If white fibrous tissue (breast or suspensory ligaments of the breast [Cooper’s ligaments]) is seen, the flap is too thick and must be cut thinner.

Draw a line around the margins of the dissection by incising the fascia at the perimeter of the field with electrocautery. This will prevent your dissecting too far in any direction. Recheck both flaps for hemostasis and place warm moist lap pads under them. Take care throughout the operation not to allow the subcutaneous fat of the underside of the flaps to become exposed and desiccated.

Anatomic Points

The breast is a conical ectodermal derivative limited to superficial fascia. The base of the breast overlies the chest wall from the second rib to the sixth and from the edge of the sternum to the midaxillary line. A lateral tongue of breast tissue—the axillary tail of Spence—extends into each axilla from the otherwise conical breast. This tail sometimes passes through the deep fascia of the axilla and approaches the pectoral group of axillary lymph nodes. Superficial to the breast is the superficial layer of the superficial fascia, whereas deep to the breast is the deep layer of superficial fascia. The subcutaneous fat lobules are small and easy to differentiate from the larger fat lobules of the breast itself.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree