Management of the Infected Femoral Graft

Matthew Mell

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The symptoms of an infected femoral graft can vary widely, from a chronically draining wound to sepsis and hemodynamic collapse.

Symptoms may have been present from hours to weeks.

Physical examination should include inspection of the surgical wounds and graft tunnels for induration, erythema, tenderness, open wounds, aneurysmal degeneration of the graft or anastomosis, or drainage.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

When possible, causative organisms should be identified prior to surgery to aid in choosing appropriate systemic antibiotics and the optimal surgical approach.

Prior to surgery, detailed imaging with computed tomographic angiography (CTA) can provide critical information for developing a cohesive plan for surgical exploration and graft removal and replacement.

Computed tomography (CT) can accurately identify anatomic signs of infection, including abscess or anastomotic aneurysm. CT can also provide clues to the extent of infection.

CTA provides high-resolution imaging of the aorta and runoff vessels, which will aid in determining the options for revascularization, including in situ reconstruction, obturator bypass, or ilioprofunda bypass.

Radionuclide scans may provide evidence for graft infection when other imaging studies are nondiagnostic.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Aggressive and wide debridement of devitalized or infected tissue must accompany graft excision and replacement in the setting of infection.

Partial or complete excision of infected prosthetic grafts is generally required to eliminate the infection.

Excision of infected autogenous graft infections may be necessary when associated with sepsis caused by Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, or Proteus spp.

Graft excision without reconstruction: Infected thrombosed grafts with adequate collateral circulation may require only excision without reconstruction.

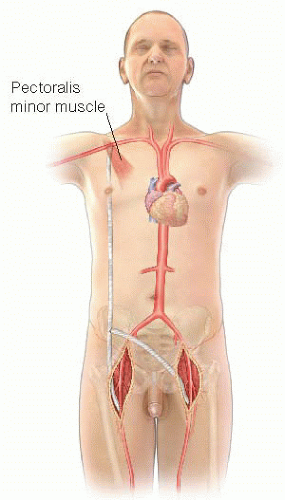

Excision and extraanatomic bypass is preferred with presence of severe sepsis and/or hemorrhage. Examples of extraanatomic bypasses include axillary-to-femoral bypass (FIG 1), obturator bypass, or cross-femoral bypass.

In situ replacement: Low-grade infections without sepsis or invasive infection and those with distal occlusive disease may be best treated with in situ graft replacement.

Graft replacement material

Graft material should be considered prior to surgery to ensure availability.

Potential options for graft material include the following:

Autogenous vein (saphenous vein, cephalic vein, basilic vein, superficial femoral vein [SFV])

Cryopreserved tissue (aorto-iliac-femoral artery, femoral vein, saphenous vein)

Prosthetic graft (rifampin-soaked Dacron™, polytetra-fluoroethylene [PTFE])

Consider the need for wound coverage:

Debridement of an infected groin wound may result in a large defect that either cannot be covered or closed. Muscle flaps can provide coverage of healthy well-vascularized tissue to protect the repair.

Small to medium defects can be covered with a sartorius muscle flap, which is divided from its attachment to the anterior superior iliac spine and mobilized medially to cover the wound.

A pedicled flap from the leg or abdominal wall may be required for larger wounds. These flaps include rectus femoris, rectus abdominis, tensor fasciae latae, or gracilis.

FIG 1 • Figure 1: Axillo-femoral bypass. Note that the proximal graft is placed behind the pectoralis minor muscle. |

TECHNIQUES

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

It is desirable when considering an extraanatomic reconstruction to revascularize before excising the infected graft. This can be accomplished with a bypass and tunnel performed across clean tissue planes. Once the bypass is completed and wounds closed, the groin can be explored and the infected graft removed. With this approach, the continuity between the superficial femoral and deep femoral arteries should be maintained by either oversewing the distal common femoral artery or anastomosing the profunda femoris artery (PFA) to the superficial femoral artery with proximal ligation (FIG 2).

Debridement of the infected site must include removal of infected or necrotic tissue and complete excision of the anastomosis. Dissection may be aided by lack of incorporation of the infected graft but also may prove challenging from extensive scarring in the reoperative field. Sharp dissection techniques are critical to minimizing the risk of inadvertent injury to vessels or adjacent structures.

It is important to send cultures of the perigraft fluid, tissue, and graft.1 Instructions should be given to the microbiology lab to perform sonication of the graft to separate biofilm from graft and maximize the bacteriology yield.