Management

Lower esophageal sphincter function in gastroesophageal reflux disease

When placed in the esophagus, more than 90% of acid is cleared into the stomach by a rapid peristalsis, but the other 10% is cleared more slowly by saliva and other host defenses. Most diseases of the esophagus, including GERD, do not cause a loss of peristalsis but do reduce the amplitude of the contractions of the fast peristaltic phase. A hiatus hernia may thus interfere with normal peristaltic waves and, therefore, prevent complete acid clearance, because acid can become trapped in the hiatal pouch. Experimentally, cisapride, a 5-HT4 agonist, has effects not only on the sphincter but also on increasing salivary volume, which have been proposed to be of benefit in facilitating the esophageal clearance of acid.

GERD may be due to an extremely hypotensive sphincter, and this was the rationale for the use of metoclopramide in the past. But it is now appreciated that this abnormality is rare and that most GERD is probably due to spontaneous but excessively prolonged (30 to 60 seconds) relaxation of the LES. The issue of transient LES relaxation (TLESR) and its role in GERD is an exciting area of pathophysiology and potentially important therapeutic development.

Current evidence indicates that TLESRs are mediated primarily via vagal pathways and that, although the basal rate for TLESRs is relatively low, gastric distention appears to be a major stimulus in initiating their occurrence. Presumably, pressure signals are transduced via mechanoreceptors in the proximal stomach (gastric cardia) that relay to the vagal sensory nucleus in the brainstem by way of vagal afferent pathways. Of particular interest is the consistent and complex nature of TLESRs, which suggests that they occur in a programmed manner, probably controlled by a pattern generator in the vagal nuclei. The currently accepted explanation as to the function of the system is that when afferent signals from the proximal stomach reach a given intensity, they excite the discharge of a pattern generator, thereby triggering LES relaxation and other complex elements (perhaps antral motility and pyloric tone) of this motility response. It is evident that the motor arm of this response resides in the vagus nerve and that it almost certainly shares common elements with swallow-induced LES relaxation. Clearly, however, so complex a system requires numerous parallel and interfaced circuits, of which few are at present defined. It is apparent, however, that pharyngeal stimulation and cholecystokinin influence TLESRs and that sleep, anesthesia, and the supine position are inhibited by them.

The stimulus for prolonged relaxations may be excessive distention of the fundus, for example, by large meals, and perhaps aberrant signals from the pharynx. Chronic reflux patients may have numerous episodes of these prolonged relaxations, even up to 12 per hour. It is also apparent that transient LES incompetence is more common with age. In this respect, the role of hiatus hernia, which had been out of vogue, has once again enjoyed an etiologic

renaissance as a component of the causation of GERD. Thus, the age-related increase in prevalence of hiatal hernias, which are capable of interfering with normal gastric mechanoreception in the fundus, may lead to delayed gastric emptying of solids and over-distention of the stomach. The debate concerning the association of a hiatus hernia and gastroesophageal reflux disease has gone back and forth for many decades. However, current beliefs are that a hiatus hernia is indeed contributory to GERD, and sophisticated analyses examining the effect of a hiatus hernia on the mechanics of gastroesophageal reflux and sphincter tone support this view.

renaissance as a component of the causation of GERD. Thus, the age-related increase in prevalence of hiatal hernias, which are capable of interfering with normal gastric mechanoreception in the fundus, may lead to delayed gastric emptying of solids and over-distention of the stomach. The debate concerning the association of a hiatus hernia and gastroesophageal reflux disease has gone back and forth for many decades. However, current beliefs are that a hiatus hernia is indeed contributory to GERD, and sophisticated analyses examining the effect of a hiatus hernia on the mechanics of gastroesophageal reflux and sphincter tone support this view.

The wide variety of surgical options available to improve the tone of an incompetent sphincter, both laparoscopic and open, suggests that none is perfect. Even different surgeons performing what they believe to be the same operation may not agree on the precise details, so it is often difficult to compare surgical results between centers and between individuals. Generally, the more the surgeon does, the more likely is the patient to be cured of reflux but also to develop dysphagia and the disabling symptoms of an inability to belch. Clearly, an experienced surgeon is the most important determinant of surgical success, and because of the potential problems of the surgery, a careful preoperative assessment of peristaltic function by a motility study is mandatory. The identification of individuals with poor motor function who will not do well with surgery is critical to avoid iatrogenically induced accentuation of the GERD. It is also necessary to make a positive diagnosis of GERD before surgery; either by endoscopy or 24-hour pH measurement. A trial of a PPI is a useful predictor of likely surgical success—if the patient’s symptoms are markedly improved by this drug, then they will probably also be helped by surgery.

Therapeutic targets

The lower esophageal sphincter

Although considerable attention has been directed to acid-pepsin refluxate in the genesis of GERD, it is the LES that remains one of the critical variables in the disease process. Unfortunately, current knowledge of sphincter physiology is limited, and in the case of the lower esophagus, this is particularly apparent. In most situations, the diagnosis of GERD is undertaken on a clinical basis, although endoscopy is used if alarm symptoms are present or a particular patient demands endoscopic confirmation of the diagnosis before institutional therapy. For the most part, however, study of the LES itself and the esophageal peristalsis is usually reserved for patients who fail acid-suppressive therapy, exhibit obvious symptoms consistent with motility problems, or are being contemplated for surgery. Documentation of the function of the LES and the motility status of the esophagus are important in the management of such individuals.

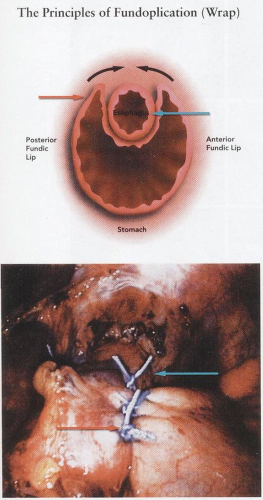

The LES in GERD appears to malfunction either by exerting a pressure zone, which is too low to prevent reflux from the stomach, or, alternatively, by producing transient episodes of relaxation that are either too frequent or prolonged. In the 1950s, surgical techniques were developed to wrap a mobilized portion of gastric fundus around the LES (Nissen, Belsey) in an attempt to increase LES pressure and obviate reflux. Innumerable modifications of this

procedure failed to provide a reliable high-pressure barrier zone to reflux, and the morbidity of the operation as an open procedure was substantial (12% to 18% complications). Furthermore, the inability to precisely calibrate the increase in lower esophageal pressure generated by the wrap led to failures due to either excessive wrapping or inadequate pressure increase. The subsequent development of prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide, designed to pharmacologically ameliorate motility disturbances associated with GERD met with limited success. This reflected the relative nonselectivity of the agent and a high incidence of adverse effects. It is, however, apparent that in certain circumstances the mechanical defects associated with GERD, which are principally located in the area of esophageal peristalsis, and particularly LES pressure, need to be addressed.

procedure failed to provide a reliable high-pressure barrier zone to reflux, and the morbidity of the operation as an open procedure was substantial (12% to 18% complications). Furthermore, the inability to precisely calibrate the increase in lower esophageal pressure generated by the wrap led to failures due to either excessive wrapping or inadequate pressure increase. The subsequent development of prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide, designed to pharmacologically ameliorate motility disturbances associated with GERD met with limited success. This reflected the relative nonselectivity of the agent and a high incidence of adverse effects. It is, however, apparent that in certain circumstances the mechanical defects associated with GERD, which are principally located in the area of esophageal peristalsis, and particularly LES pressure, need to be addressed.

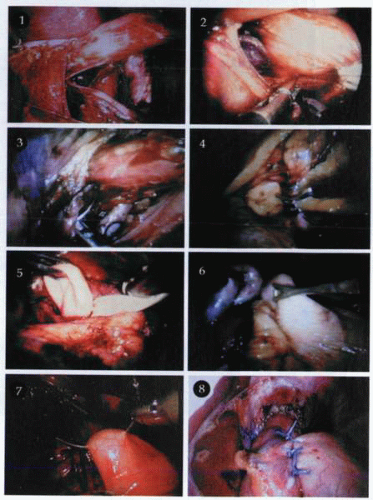

Fundoplication

In circumstances in which the patient is young, requires maintenance acid-suppression therapy, is fit for surgery, and desires an operation, manometric testing should be undertaken to confirm the absence of esophageal peristaltic abnormalities and define the function of the LES. If all the criteria for surgery are met, the most appropriate operation at this time appears to be a Nissen fundoplication undertaken by laparoscopic technique. In brief, this consists of the introduction of a number of ports into the upper abdomen whereby dissection and mobilization of the fundus of the stomach and the esophagus can be undertaken. A gastric wrap is performed, having mobilized the lower 4 to 5 cm of the esophagus and moved the stomach behind it before suturing it anteriorly in front of the esophagus through the residual portion of the gastric fundus, which has been mobilized but not moved behind the esophagus. Critical areas involve the need to avoid damage to the stomach and esophagus as well as to the vagus nerves.

The diameter of the esophagus embraced by the wrap is determined by insertion of a large bougie through the gastroesophageal junction from the mouth. Results using this technique have been reported as successful in up to 85% of patients with a morbidity level varying between 10% and 15%. The precise details of surgery and its advantages and disadvantages have been dealt with in the surgical section. Under some circumstances, however, both physicians and patients would prefer to avoid surgery, and in such cases, the use of prokinetic drugs in addition to antisecretory agents should be strongly considered.

Prokinetic agents

Given the fact that acid appears to be a major inciting event in esophagitis, initial attention was directed at neutralization or suppression of acid secretion. The issue of decreasing reflux by addressing sphincter function, esophageal clearance of acid, or gastric emptying has led to an interest in identifying pharmacotherapeutic targets and agents that have a motor rather than a secretory function. Although most successful therapies have decreased acid secretion and volume with H2 receptor antagonists and especially PPIs, the use of either mucosal protectants, such as sucralfate, or prokinetic agents, such as cisapride, has had minimal effect on the treatment of GERD except in occasional patients. Thus, in spite of serious consideration that GERD is a motility disorder, such promotility drugs as bethanechol, metoclopramide, and cisapride have had marginal efficacy in treating GERD patients except in patients with nonerosive disease or dyspepsia with associated delayed gastric emptying. Although a variety of mechanisms were proposed whereby such agents purportedly increased LES pressure and improved acid clearance, in retrospect, it is probable that they did little more than improve gastric emptying. Of particular relevance to current concepts of GERD etiology, it is apparent that none

of these putative promotility agents had any effect on the major motor mechanism underlying reflux episodes, TLESRs.

of these putative promotility agents had any effect on the major motor mechanism underlying reflux episodes, TLESRs.

Because TLESRs appear to be a key mechanism underlying most episodes of gastroesophageal reflux, the ability to regulate them pharmacologically is paramount to the success of therapy. It is now evident that TLESRs account for virtually all reflux episodes in healthy subjects and most (55% to 80%) reflux episodes in GERD patients. Although such patients usually exhibit no esophagitis (NERD) or only mild erosions, they collectively account for as much as 80% of all patients with reflux disease. Furthermore, it is apparent that individuals with severe esophagitis not only reflux via TLESRs but also have frequent reflux episodes during periods of prolonged absent basal LES pressure.

Prokinetic agents are those that are intended to restore, normalize, and facilitate motility in the gastrointestinal tract. The development of this group of pharmacologic agents is historically traceable to the appreciation of the role of dopaminergic receptors in gut smooth muscle. The recognition of their presence stimulated an investigation of agents that would even neutralize or antagonize the inhibitory effects of dopamine on gut motility. The first agent of this class was metoclopramide, which was useful in that it improved gastric emptying, accelerated transit through the small bowel, and provided for the first time an agent capable of modulating gut motility. Unfortunately, metoclopramide crosses the blood-brain barrier, resulting in CNS antidopaminergic effects, and up to 20% of individuals suffered from experimental side effects of varying degrees of intensity. Further problems related to the generation of hyperprolactinemia include breast enlargement, nipple tenderness, galactorrhea, and menstrual irregularities. To a certain extent, these disadvantages were overcome by the development of domperidone, which, although it had minimal experimental side effects, still caused hyperprolactinemia and its related symptomatology. Its effect on enhancing motility of the esophagus, stomach, and small bowel was useful, but its primary therapeutic usefulness was its antiemetic properties at the chemoreceptor trigger site.

The subsequent development of cisapride, an agonist of the serotonin receptor 5-HT4, was a significant improvement over both previous agents. This prokinetic agent facilitates the release of ACh from postganglionic cholinergic fibers within the myenteric plexus. The overall result of this biochemical effect has been to improve propulsive motor activity of the esophagus, stomach, small bowel, and large bowel. In addition to its motor effects, cisapride has been documented to enhance salivary secretion by stimulation of the esophagosalivary reflex, with the result that increased saliva flow as well as the protective agent within it (bicarbonate, glycoconjugate, EGF, and PGE2) are delivered in larger quantities to the LES area and are postulated to accentuate healing. Cisapride is a substituted piperidinyl benzamide, which is chemically related to metoclopramide but did not exhibit the major CNS effects. Nevertheless, somnolence and fatigue have been reported as well as some experimental effects.

The particular problem with cisapride has been its relative nonselectivity in terms of a target of smooth muscle function. In some individuals, serious diarrhea and abdominal pain have proved to be major drawbacks in its use. Nevertheless, cisapride has been demonstrated to significantly increase lower

esophageal pressure as well as to promote gastric emptying. Given its positive effects on promoting esophageal peristalsis, the sum of these pharmacologic events has been to produce a prokinetic agent of therapeutic benefit in patients with GERD. Indeed, in individuals in whom acid suppression may not adequately obviate relapse, the use of cisapride as an adjuvant agent has been met with some reasonable success.

esophageal pressure as well as to promote gastric emptying. Given its positive effects on promoting esophageal peristalsis, the sum of these pharmacologic events has been to produce a prokinetic agent of therapeutic benefit in patients with GERD. Indeed, in individuals in whom acid suppression may not adequately obviate relapse, the use of cisapride as an adjuvant agent has been met with some reasonable success.

A number of studies have demonstrated that cisapride alone is more effective than placebo in symptom relief and healing in patients with heartburn of the esophagitis grade 0 to 3 range. Similarly, it has been reported that episodes of gastroesophageal reflux are decreased in patients taking cisapride, and that in individuals using acid suppression in combination with cisapride, efficacy of symptom relief and healing are greater than when acid suppression alone is used. The widespread distribution of the 5-HT4 receptor has resulted in very serious side effects, particularly in children. This drug has thus been withdrawn from the market. Perhaps, also, the selectivity of this agonist is less than that required, and the side effects are due to actions on other receptors.

Tweaking transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations

In the 1990s, the ability to manipulate TLESRs pharmacologically became possible with the identification of several agents that substantially diminished this phenomenon. Although the magnitude of TLESR reduction required to achieve a clinically significant reduction in reflux symptoms has not been precisely defined, it has been suggested that a reduction of at least 50% is necessary to assure clinical efficacy. To date, a wide variety of agents, including CCK1 antagonists, anticholinergic agents, nitric oxide synthase inhibitors, morphine, and γ-aminobutyric acid β (GABAβ) agonists have been studied in humans.

Anticholinergic agents

After the observation in healthy volunteers that intravenous atropine reduced the rate of TLESRs by nearly 60%, a study in GERD patients produced similar findings. Current evidence suggests a central site of action, because selective peripheral anticholinergic agents, which do not cross the blood-brain barrier, fail to inhibit TLESRs. It is, however, unlikely that anticholinergic agents will be clinically effective because of their deleterious effects on supine acid clearance and worrisome side-effect profile.

Cholecystokinin

Given the well-accepted data reporting the presence of a variety of CCK receptor subtypes on neurons and the LES muscle and the demonstration that meals and/or gastric distention stimulate the release of CCK, it was predictable that the peptide would influence TLESRs. Furthermore, because animal studies showed that CCK infusion increased the rate of TLESRs triggered by gastric distention, the augmentation of TLESRs by food intake and gastric distention provided a logical potential treatment target. Thus, devazepide, a CCK1 but not a CCK2 antagonist, was demonstrated to be effective in decreasing gastric distention-induced TLESRs. Because devazepide was not effective when administered into the CNS, it

seemed likely that CCK was acting either via the proximal stomach or on the afferent nerves. Subsequent human studies demonstrated that the CCK1 antagonist loxiglumide inhibited the rate of TLESRs induced by meals and gastric distention by approximately 40%, further suggesting a potential therapeutic opportunity. Unfortunately, an orally effective CCK1 antagonist is not yet available, and the feasibility of TLESR management using intravenous preparations seems low.

seemed likely that CCK was acting either via the proximal stomach or on the afferent nerves. Subsequent human studies demonstrated that the CCK1 antagonist loxiglumide inhibited the rate of TLESRs induced by meals and gastric distention by approximately 40%, further suggesting a potential therapeutic opportunity. Unfortunately, an orally effective CCK1 antagonist is not yet available, and the feasibility of TLESR management using intravenous preparations seems low.

Nitric oxide

The role of nitric oxide in sphincter function remains an exciting area of debate, and, indeed, nitric oxide is the major postganglionic inhibitory neurotransmitter to the LES, and nitrergic neurons are present in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Its potential role in the modulation of LES pressure was confirmed by a series of animal studies that reported not only that the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-MNME inhibited the rate of TLESRs but also that the effect could be reversed by L-arginine. Of further interest were human volunteer studies that reported that L-NMMA inhibited TLESRs induced by gastric distention by more than 75%. Although the reduction in meal-induced TLESRs was only 25%, the potential of such compounds is indisputable. Unfortunately, no orally effective nitric oxide inhibitor is currently available, and the inhibition of nitric oxide is associated with widespread alterations in gastrointestinal motility and substantial changes in the cardiovascular, urinary, and respiratory systems.

Morphine

Because opioid nerves have been demonstrated in the myenteric plexus of the LES in humans, and morphine has been noted to inhibit LES relaxation caused by swallowing and balloon distention, a possible therapeutic role has been proposed. Thus, the demonstration that intravenous morphine given to GERD patients inhibited TLESRs by 50% while also decreasing the number of reflux episodes further supported the contention that a therapeutic role might exist. Because the effect of morphine is blocked completely by naloxone, it is likely that its activity is mediated through opioid receptors located in the CNS. The likelihood of a central effect is further substantiated by the fact that the peripherally active opioid—loperamide—does not effect TLESRs. At this time, the unacceptable side effects of the agent, including addiction and constipation, seriously preclude its consideration as a viable therapeutic strategy.

GABAB agonists

GABAB is one of the major inhibitory neurotransmitters of the CNS, and GABAB receptors are present at numerous sites within the CNS and peripheral nervous system. Baclofen, the prototype agent, acts through inhibition of transmitter release from muscle spindle afferents and is currently used clinically for the treatment of muscle spasticity but has been demonstrated to be a powerful inhibitor of TLESRs. Although the precise mechanism of its action has not been defined, animal studies suggest that baclofen exerts its effect by modulating the trigger sensitivity of gastric mechanoreceptor and the central pathway between vagal afferents and efferents.

In both healthy subjects and those with GERD, single oral doses (40 mg) of baclofen have been demonstrated to decrease the rate of TLESRs by more than 50%, with a concomitant 60% decrease in the rate of reflux episodes. Thus, in a field (sphincter function regulation) where there are few reasonable candidates, GABAB agonists currently appear to be the most promising new class of agents for controlling the rate of TLESRs. A subsequent encouraging preliminary study in healthy subjects and reflux patients found that oral baclofen (40 mg twice a day) decreased acid and nonacid reflux and symptoms associated with these refluxates. Of note is the fact that, compared with other available agents, baclofen is available as an oral agent and does not exhibit adverse effects on basal LES pressure or acid clearance. Unfortunately, side effects are common and include drowsiness, nausea, and the lowering of the threshold for seizures. Thus, although baclofen appears promising in principle, it is evident that novel agents with more precisely defined molecular targets are necessary before widespread clinical use is possible.

Gastric acidity

Gastric juice is harmful to esophageal squamous mucosa. In general, the secretion of acid, pepsin, and bile as measured by classic secretory studies using nasogastric tubes is no different in patients with or without GERD, suggesting that hypersecretion is not the cause of the disease. Indeed, most experimental models suggest that it is not acid alone that is injurious. The damage is due to the presence of other contents of the refluxate, including at least pepsin, bile, ingested material, and lysolecithin.

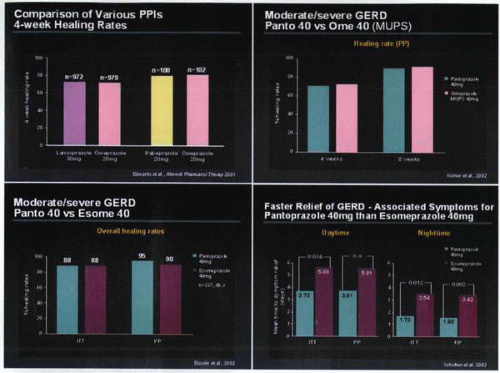

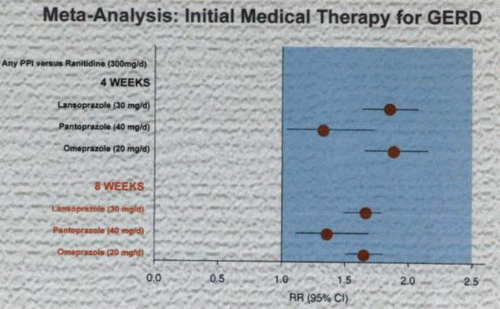

Although acid may have direct effects on the esophageal mucosa, including widening intercellular spaces and altering the esophageal potential difference, its main function may be to facilitate the damage initiated by pepsin and bile as well as activating pepsinogen to pepsin. Although acid may not be the only cause of the damage in GERD, acid suppression is a very effective treatment. In the evaluation of data acquired by metaanalysis, it is apparent that the greater the acid suppression, the better the healing of esophagitis and the more rapidly the symptoms are relieved. It is interesting that certain regulatory agencies have failed to accept this concept and still require head-to-head clinical studies between individual acid-suppression medications to prove efficacy. In general, the most effective acid suppression is achieved with PPIs, and there are currently several of these available, including pantoprazole, lansoprazole, and omeprazole. The latter agent was the initial pump inhibitor, shown to be far more effective than H2 receptor antagonists in the healing of GERD, but subsequently, many compounds of the PPI class of drugs have been shown to exhibit equivalent superiority.

More recently, esomeprazole, an (S)-isomer of omeprazole, has been developed. It is the first PPI to be developed as an optical isomer and appears to

have an improved pharmacokinetic profile that confers increased systemic exposure and less interindividual variability compared with omeprazole. It is proposed that this produces more effective suppression of gastric acid production compared with other PPIs. Of note are the observations that esomeprazole is well tolerated, with a spectrum and incidence of adverse events similar to those associated with omeprazole. Several large, double-blind, randomized trials have noted higher rates of endoscopically confirmed healing of erosive esophagitis and resolution of heartburn in patients with GERD receiving 8 weeks of esomeprazole, 40 mg o.d., compared with those receiving omeprazole, 20 mg o.d., or lansoprazole, 30 mg o.d. Similarly, esomeprazole, 10, 20, or 40 mg o.d., was significantly more effective than placebo in two 6-month, randomized, double-blind trials in the maintenance of healed erosive esophagitis. In a separate 6-month, randomized, double-blind trial, esomeprazole, 20 mg o.d., was more effective than lansoprazole, 15 mg, in the maintenance of healed erosive esophagitis, and healing of esophagitis was also effectively maintained by esomeprazole, 40 mg o.d., in a 12-month noncomparative trial. Esomeprazole, 20 or 40 mg o.d., effectively relieved heartburn in patients with GERD without esophagitis in two 4-week, placebo-controlled trials. Similarly, studies in endoscopy-negative patients, or in both esophagitis- and endoscopy-negative patients, have demonstrated good efficacy for esomeprazole, with high levels of symptom control achieved in the first 7 days of therapy. The greatest advantage for esomeprazole appears to be its improved healing rates in the more severe grades of esophagitis as compared to omeprazole, although recent studies suggest that there is no appreciable difference between it and pantoprazole, and that on a milligram-for-milligram basis, all PPIs appear to be equivalent.

have an improved pharmacokinetic profile that confers increased systemic exposure and less interindividual variability compared with omeprazole. It is proposed that this produces more effective suppression of gastric acid production compared with other PPIs. Of note are the observations that esomeprazole is well tolerated, with a spectrum and incidence of adverse events similar to those associated with omeprazole. Several large, double-blind, randomized trials have noted higher rates of endoscopically confirmed healing of erosive esophagitis and resolution of heartburn in patients with GERD receiving 8 weeks of esomeprazole, 40 mg o.d., compared with those receiving omeprazole, 20 mg o.d., or lansoprazole, 30 mg o.d. Similarly, esomeprazole, 10, 20, or 40 mg o.d., was significantly more effective than placebo in two 6-month, randomized, double-blind trials in the maintenance of healed erosive esophagitis. In a separate 6-month, randomized, double-blind trial, esomeprazole, 20 mg o.d., was more effective than lansoprazole, 15 mg, in the maintenance of healed erosive esophagitis, and healing of esophagitis was also effectively maintained by esomeprazole, 40 mg o.d., in a 12-month noncomparative trial. Esomeprazole, 20 or 40 mg o.d., effectively relieved heartburn in patients with GERD without esophagitis in two 4-week, placebo-controlled trials. Similarly, studies in endoscopy-negative patients, or in both esophagitis- and endoscopy-negative patients, have demonstrated good efficacy for esomeprazole, with high levels of symptom control achieved in the first 7 days of therapy. The greatest advantage for esomeprazole appears to be its improved healing rates in the more severe grades of esophagitis as compared to omeprazole, although recent studies suggest that there is no appreciable difference between it and pantoprazole, and that on a milligram-for-milligram basis, all PPIs appear to be equivalent.

There is little difference in the 1-month healing rates between any of these agents. Lansoprazole at a dose of 30 mg daily is claimed to be more effective than omeprazole, 20 mg daily, for symptom relief, perhaps just reflecting the higher dose or superior bioavailability of lansoprazole. There is also some person-to-person variability in the secretory response to omeprazole and, to a lesser degree, to lansoprazole. Pantoprazole appears to have the most advantageous pharmacokinetic profile and is negligible in its effects on the hepatic P450 cytochrome system. This latter factor may be of relevance in the context that the vast majority of older patients take other medications as well as PPIs.

Despite the efficacy of these medications, at least 10% of all patients continue to have symptoms after 2 months of PPI therapy. This reflects the fact that many patients present for treatment at a point well into the evolution of the disease process and exhibit an esophagus that is either scarred or so damaged that the healing process cannot maintain mucosal integrity in the presence of anything other than the presence of the most limited amounts of acid or pepsin. This further emphasizes the need not only to tailor treatment for GERD to the individual patient but also to ensure early institution of therapy with PPIs rather than observation of repeated recurrence of symptomatology and accentuation of damage during a trial of inadequate acid inhibitory therapy.

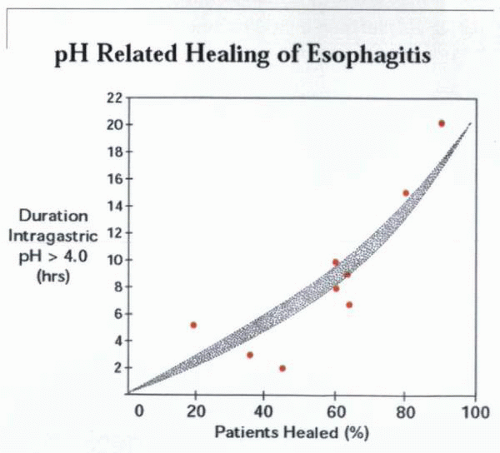

Gastroesophageal reflux disease and esophageal pH

There is a clear predictive relationship between intragastric pH and intraesophageal pH, as both correlate with the healing of esophagitis. The greater the severity of the esophagitis, the greater the requirement for acid suppression. The conventional pH threshold for aggressive versus nonaggressive reflux is regarded as a pH of 4.0, and this has been supported by pH measurements in patients with defined severities of GERD. Overall, it is apparent that the severity of mucosal injury in GERD is dependent on the pH of the reflux material and its dwell time in the esophagus. In this respect, 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring has proved to be the most effective measurement of gastroesophageal reflux, because it records both the pH of the reflux and the duration of the exposure. It is evident that the daily duration of time for which the intragastric pH is elevated to 4.0 or higher correlates closely with the healing of erosive reflux esophagitis. Nevertheless, esophageal pH monitoring studies reveal in some patients the presence of GERD despite normal or near normal acidic exposure values.

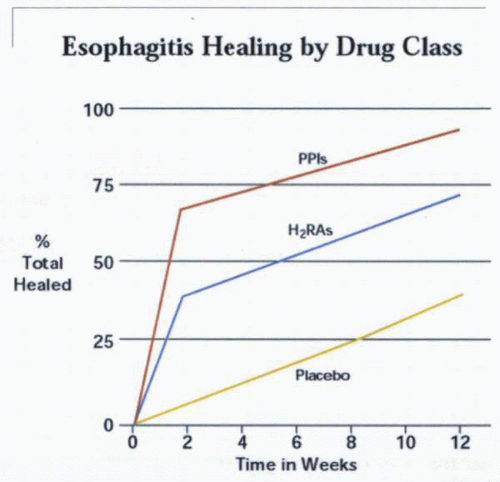

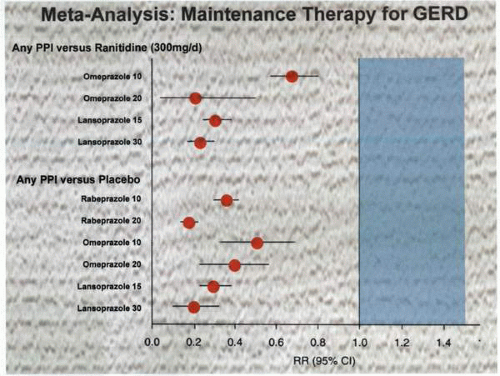

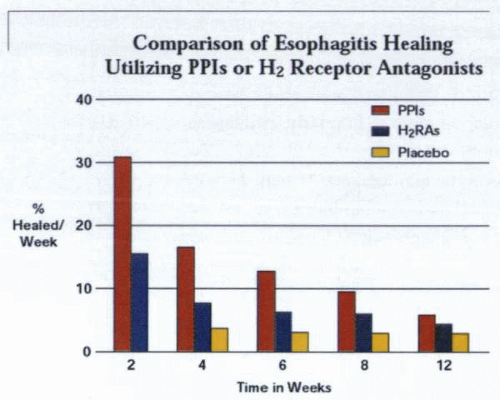

The percentage of patients with esophagitis that heal over time is dependent on the class of agent used for acid suppression. |

This paradox probably reflects alterations in reflux patterns that vary from day to day as well as variations in pH between different regions of the esophagus. Esophageal pH rises as the distance from the LES increases, and in addition, pH appears to be lower at the peaks of the esophageal folds, which are exposed to acid as opposed to the tufts, where there is a greater degree of protection afforded by bicarbonate and mucus. This variation in esophageal pH is presumably responsible for the linear distribution of erosive esophagitis evident at endoscopy in some patients. Overall, it does not appear that patients with GERD are acid hypersecretors. Nevertheless, repeated measurements of 24-hour intragastric acidity in individual patients reveal considerable variations.

In some patients, abnormal duodenal gastric reflux may make gastric juice especially aggressive to esophageal mucosa. In this respect, delayed gastric emptying may contribute significantly to pathologic gastroesophageal reflux. Similarly, abnormally frequent transient LES relaxation, as well as inappropriate esophageal clearance and the presence of a hiatal hernia, may contribute to the development of GERD. Twenty-four-hour esophageal pH monitoring in endoscopically negative or mild reflux disease has shown that most acid exposure occurs during the day in the postprandial state. Furthermore, several esophageal-monitoring studies have demonstrated that individuals with Barrett’s esophagus exhibit high levels of esophageal exposure to gastric reflux. Nevertheless, rigorous data supporting that Barrett’s esophagus is linearly related to the level of acid reflux are not available.

The key role of acids in the development of GERD is best exemplified in patients with gastrinoma disease, in which peptic esophagitis is directly related to the level of acid suppression achievable. It is likely that the marginal efficacy of H2 receptor antagonists in the management of GERD is related to their failure to control esophageal acid exposure. Other factors involved in the development of GERD that are pH related include the ability of the esophagus to clear acid and to deal

with activated pepsinogen. In up to 50% of patients with GERD, it has been demonstrated that the higher the acid concentration in the refluxate, the longer it requires for clearance. The reasons for the diminished rate of clearance are at this time unclear but may represent either abnormally low swallowing rates or ineffective primary or secondary peristalsis. Although salivary bicarbonate is of importance in determining esophageal acid clearance, little information is available on salivary gland function in GERD patients. The pH necessary to activate pepsinogen is an important variable in the sensitivity of the esophageal epithelium through acid peptic insult. The higher the pH, the further outside the optimum pH profile for pepsinogen activation and, hence, the less the likelihood of damage. A similar pathogenesis is probably involved in damage caused by bile acids, but this usually reflects a smaller subgroup of patients who have had previous gastric surgery or exhibit major motility disorders.

with activated pepsinogen. In up to 50% of patients with GERD, it has been demonstrated that the higher the acid concentration in the refluxate, the longer it requires for clearance. The reasons for the diminished rate of clearance are at this time unclear but may represent either abnormally low swallowing rates or ineffective primary or secondary peristalsis. Although salivary bicarbonate is of importance in determining esophageal acid clearance, little information is available on salivary gland function in GERD patients. The pH necessary to activate pepsinogen is an important variable in the sensitivity of the esophageal epithelium through acid peptic insult. The higher the pH, the further outside the optimum pH profile for pepsinogen activation and, hence, the less the likelihood of damage. A similar pathogenesis is probably involved in damage caused by bile acids, but this usually reflects a smaller subgroup of patients who have had previous gastric surgery or exhibit major motility disorders.

Given the fact that the degree of esophageal acid exposure correlates almost linearly with the severity of esophagitis, the primary aim of acid-suppression therapy is to raise the pH of the refluxate. In this respect, H2 receptor antagonists are not effective in anything other than the mildest of GERD situations due to their inability to maintain a pH greater than 4.0 for a sustained period. A number of metaanalytic studies have indicated that a threshold of pH 4.0 appears to be the critical determinant for ensuring esophageal healing. Thus, the longer the esophageal acid exposure to a pH greater than 4.0, the more likely it is that healing will occur. The rapid relapse of esophagitis on withdrawal of acid-suppressive therapy indicates that the duration of therapy is of critical relevance in determining complete healing. In this respect, agents such as the PPI class of drugs are clearly superior, given their ability to not only provide a higher degree of acid suppression but also to maintain pH levels elevated both during the daytime and the nighttime, regardless of stimulation by meals. It may well be that the efficacy of the prokinetic agents is to a certain extent provided by their effect on acid clearance. Relatively poor responses to prokinetic agents suggest that abnormally delayed gastric emptying may be a relatively minor factor in the pathogenesis of GERD. Because they do not result in a major decrease in the frequency of reflux episodes, it seems likely that, at this time, the suppression of gastric acid secretion will remain the primary means of GERD therapy.

Helicobacter pylori

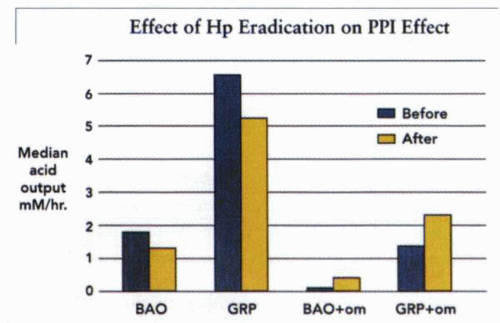

It is interesting to note that the increase in the reported prevalence of GERD has coincided over the last 50 years or so with a natural decline in H. pylori infection in the West. This has led to some speculation that the two may be causally related and that H. pylori may have been of some symbiotic benefit to humans. One possible mechanism by which H. pylori may influence GERD is through engendering an alteration in acid secretion.

Although H. pylori increases acid secretion in patients with duodenal ulcer disease, it may be responsible for decreasing acid secretion in those individuals infected early in life who develop gastritis of the gastric corpus. Several lines of evidence support this view. Thus, in Japan, the gastric cancer and H. pylori incidence rates have fallen dramatically over the last 20 years, and there has been an associated increase in gastric acid secretion in the population, as well as an increasing recognition of GERD. It has been reported that the eradication of H. pylori in a series of people with duodenal ulcer disease led to some of them developing GERD for the first time. Although this finding remains controversial, it raises interesting questions and cannot be ignored. The issue of whether harboring H. pylori in the stomach is associated with an unexpected beneficial effect of the bacterium by the protection afforded from GERD may be quixotic but requires examination.

Another observation of relevance is that lower doses of antisecretory medications appear effective in the management of GERD when H. pylori is

present. The generation of NH3 by H. pylori is likely able to neutralize a significant portion of nighttime acid secretion when this is already inhibited by PPIs. This would explain the observation that eradication of the organism decreases intragastric pH, particularly at night. Currently, the consensus appears to be that eradication of the pathogen has little effect on the incidence of GERD in the infected population. The potential benefit to the individual of retaining his or her H. pylori to lower the PPI dose when treating GERD is offset by the reports suggesting that the development of gastric atrophy, a preneoplastic change, is accelerated by the presence of H. pylori in patients taking omeprazole. This controversial finding initially provoked considerable skepticism but has more recently acquired further support in studies that addressed the same question. Given the considerable support for the use of maintenance PPI treatment in the management of GERD, this issue is of critical relevance and requires definitive resolution. At this time, the safest approach is eradication of H. pylori-positive GERD in patients taking PPIs on a chronic basis.

present. The generation of NH3 by H. pylori is likely able to neutralize a significant portion of nighttime acid secretion when this is already inhibited by PPIs. This would explain the observation that eradication of the organism decreases intragastric pH, particularly at night. Currently, the consensus appears to be that eradication of the pathogen has little effect on the incidence of GERD in the infected population. The potential benefit to the individual of retaining his or her H. pylori to lower the PPI dose when treating GERD is offset by the reports suggesting that the development of gastric atrophy, a preneoplastic change, is accelerated by the presence of H. pylori in patients taking omeprazole. This controversial finding initially provoked considerable skepticism but has more recently acquired further support in studies that addressed the same question. Given the considerable support for the use of maintenance PPI treatment in the management of GERD, this issue is of critical relevance and requires definitive resolution. At this time, the safest approach is eradication of H. pylori-positive GERD in patients taking PPIs on a chronic basis.

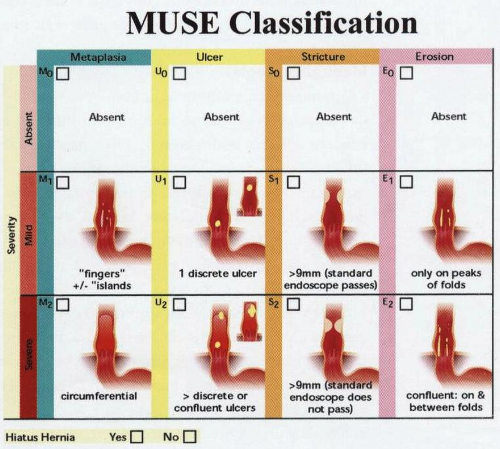

Determination of gastroesophageal reflux disease and management

In general practice, dyspepsia occurs in approximately half of the population, and even patients who have reflux symptoms often also have ulcer-like symptoms. The endoscopic evaluation of esophagitis remains an area of both controversy and difficulty. There is no completely satisfactory classification, and many schemes vie for widespread acceptance. Even within individual classifications, agreement between the classifiers is not uniform. Although agreement between observers is good for severe changes of esophagitis—stricture and erosions—there is often extremely poor agreement between observers for minor changes. Because the prevalence of endoscopy-negative reflux disease far outweighs those

who have positive endoscopic findings, the precise role of endoscopy in diagnosis needs serious consideration. Given its expense, invasiveness, and relative insensitivity as a diagnostic tool, initial enthusiasm has been replaced by a healthy degree of skepticism. A once-in-a-lifetime endoscopy, toward the beginning of treatment rather than later, is probably a useful maneuver, if only to rule out other unexpected lesions. However, repeat endoscopy in a patient with uncomplicated GERD is probably not indicated unless Barrett’s esophagus has been identified and verified. In such individuals, cost-effectiveness analyses have suggested that surveillance should be performed every 5 years, although given the current reduction in endoscopy costs in the United States, the financial equation may change in favor of more frequent evaluation.

who have positive endoscopic findings, the precise role of endoscopy in diagnosis needs serious consideration. Given its expense, invasiveness, and relative insensitivity as a diagnostic tool, initial enthusiasm has been replaced by a healthy degree of skepticism. A once-in-a-lifetime endoscopy, toward the beginning of treatment rather than later, is probably a useful maneuver, if only to rule out other unexpected lesions. However, repeat endoscopy in a patient with uncomplicated GERD is probably not indicated unless Barrett’s esophagus has been identified and verified. In such individuals, cost-effectiveness analyses have suggested that surveillance should be performed every 5 years, although given the current reduction in endoscopy costs in the United States, the financial equation may change in favor of more frequent evaluation.

Medical strategies

A number of algorithms have been developed for the management of erosive esophagitis. These tend to be somewhat different from country to country or between different health systems. Once the diagnosis of GERD has been established, an attempt at lifestyle modification, with or without antacids, mucosal protectant agents, or alginic acid, is usually undertaken as an initial step. If unsuccessful, an acid-inhibitory agent is then introduced into the therapeutic regimen. In patients with mild disease (grade 1 to 2), an H2 receptor antagonist is often used. If this fails (failure to relieve symptoms or relapse on cessation of therapy), a PPI is usually used. Because a significant number of patients fail to heal with the H2 receptor antagonist therapy or, alternatively, relapse, PPIs have increasingly been rightly considered as a first line of therapy. Within broad parameters, the general algorithm used includes initial evaluation by endoscopic examination with biopsy, followed by 24-hour pH monitoring and measurement of LES pressure, followed by an 8-week course of a PPI. If symptom relief and healing do not occur under these circumstances, a second course of PPI therapy

is usually undertaken (often at a higher or divided dosage). Depending on the age of the patient, severity of symptomatology, and the physician’s level of concern, a number of relapses may lead either to the introduction of a prokinetic agent or, alternatively, to the consideration of surgery. For the most part, the latter option now entails laparoscopic surgery. In those individuals who at initial diagnosis exhibit evidence of a complication of GERD, the use of short-term medical therapy before surgical intervention is usual. Using this general management strategy or reasonable variations thereof, it appears that between 85% and 95% of all patients can be adequately managed medically, and some 5% to 15% of patients either exhibit complications or are nonamenable to long-term acid-inhibitory therapy and thus require consideration for surgery.

is usually undertaken (often at a higher or divided dosage). Depending on the age of the patient, severity of symptomatology, and the physician’s level of concern, a number of relapses may lead either to the introduction of a prokinetic agent or, alternatively, to the consideration of surgery. For the most part, the latter option now entails laparoscopic surgery. In those individuals who at initial diagnosis exhibit evidence of a complication of GERD, the use of short-term medical therapy before surgical intervention is usual. Using this general management strategy or reasonable variations thereof, it appears that between 85% and 95% of all patients can be adequately managed medically, and some 5% to 15% of patients either exhibit complications or are nonamenable to long-term acid-inhibitory therapy and thus require consideration for surgery.

In a review of 31 randomized studies performed between 1986 and 1995, initial medical therapy over 8 to 12 weeks resulted in an overall healing rate with PPIs of 87.1% (n = 1,725 patients), H2 receptor antagonists of 57.2% (n = 2,262), prokinetic agents of 66.0% (n = 209), and placebo of 23.7% (n = 719). The prokinetic data are probably too small to enable reasonable comparison. In a further evaluation of 36 studies undertaken between 1989 and 1995, the relapse rate for H2 receptor antagonists was 77.3%, compared to an overall relapse rate of 26% for the PPI group of drugs. When analyzed individually on an agent-specific basis, the relapse rate after short-term treatment was 39.2% for omeprazole, 22.3% for lansoprazole, and 17.5% for pantoprazole.

In regard to the long-term outcome after maintenance therapy with omeprazole or lansoprazole, a remission rate of 79% to 90% can be achieved over a 12-month period. The issue of adverse events using medical therapy was evaluated in 16,816 patients, comprising nine studies performed between 1989 and 1995. The majority of these events were minor and rarely required cessation of the therapy. They included headache, diarrhea, abdominal pain, skin rash, and drowsiness. When summated, treatment-related incidents occurred in the H2 receptor antagonist group in approximately 23%, whereas use of the PPI class of agent was associated with reportable events in approximately 18%. This difference was not statistically significant. Individually adverse effects were reported with pantoprazole in 13.0%, lansoprazole in 18.0%, and omeprazole in 22.3% of patients. These are no different from placebo events.

In regard to the long-term outcome after maintenance therapy with omeprazole or lansoprazole, a remission rate of 79% to 90% can be achieved over a 12-month period. The issue of adverse events using medical therapy was evaluated in 16,816 patients, comprising nine studies performed between 1989 and 1995. The majority of these events were minor and rarely required cessation of the therapy. They included headache, diarrhea, abdominal pain, skin rash, and drowsiness. When summated, treatment-related incidents occurred in the H2 receptor antagonist group in approximately 23%, whereas use of the PPI class of agent was associated with reportable events in approximately 18%. This difference was not statistically significant. Individually adverse effects were reported with pantoprazole in 13.0%, lansoprazole in 18.0%, and omeprazole in 22.3% of patients. These are no different from placebo events.

Surgical and endoscopic strategies

Endoscopic antireflux therapies

There has been widespread enthusiasm to find less invasive strategies for dealing with reflux than surgery and to decrease life-long exposure to acid-suppressive medications. As a consequence, luminally delivered physical antireflux therapies are being explored to obviate some of the limitations or disadvantages of medical therapy or conventional laparoscopic antireflux surgery. This has led to the introduction of a variety of procedures that are minimally invasive; intended to be undertaken as a same-day, outpatient procedure; and suitable for retreatment, reversal, or both, although absolving patients from the necessity of daily medication. Over the last decade, a diverse spectrum of such candidate therapies has emerged. Unfortunately, most focus on the relatively simplistic notion of augmenting or bolstering the LES. Furthermore, few techniques have been subjected to rigorous scrutiny or evaluated in prospective randomized studies; hence, the data on their efficacy are less than assured. An additional problem with most of these novel strategies is that patients with less severe levels of esophagitis have been treated; hence, results may be optimistically unrealistic. The notion that the therapy is luminally delivered has led to a false perception that it may, therefore, be deemed safe; such is clearly not the case.

Radiofrequency energy delivery

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree