Introduction

This chapter will start with identifying the biggest contrasts between physician and physician leaders. In understanding both the contrast and comparative elements of each role, you can prepare to make a progressive, positive transition into your new role as a healthcare or physician leader. We will then move to some initial practical perspectives and strategies which will help you undertake this critical transition effectively and employ this handbook as a readily useful reference for undertaking your new role.

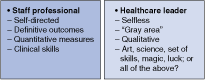

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN PROFESSIONAL AND MANAGERIAL ROLES

As a healthcare professional, you are in a position that is more self-directed. Your job description reflects a range of activities that you pretty much control and that require mastery of some technical discipline. (Here, technical discipline includes specific medical skills, as well as acumen in accounting, information technology, customer care, and a host of other specific skills.) In your daily work, you make technical judgments without undue reliance on others, and external and internal organizational dynamics have little impact on your daily activities.

In essence, professionals are responsible first and foremost for their own performance: you are the key factor in determining the level of success you experience and what contribution you make to your organization.

As a physician leader, by contrast, you are in an area of selfless service (Figure 1–1), which depicts the applicable of The Peter Principle to health care. Rather than focusing on self-performance, healthcare managers supervise the activities of others. You have a great degree of control over and responsibility for others’ activities. Your time is governed by the work activities and needs of your reporting staff, as well as the needs of your organization. Your work is constantly interrupted by people problems, organizational mandates, and change in work direction generated by upper management. Furthermore, your first responsibility is to the individuals you supervise, not to yourself. This means that your priorities and interests often take a backseat.

As a healthcare professional, you have autonomous control over your work responsibilities. In many cases, your work activity is primarily governed by a job description, and you perform your tasks based on deadlines, processes, and procedures. Unless an emergency arises, you can work at your own pace and accomplish the goals you desire, based on your own performance and motivation.

As a manager, circumstances and situations control your action flow. The organizational contribution your department makes is the main factor in determining your workflow and your daily responsibilities. As emergencies arise, you must mobilize your entire department and determine who will work to attain specific objectives. Flexibility is a key factor in your success; you must be positively reactive, adaptable, and versatile in undertaking your management responsibilities.

The roles of most healthcare professionals usually lead to a variety of quantitative outcomes. In general, performance as a professional is assessed based on meeting quantitative outcomes on a regular basis.

For example:

A laboratory technician conducts analysis and assays, which produces numerical (quantitative) outcomes.

A staff pharmacist is responsible for filling a set amount of prescriptions on a daily basis.

A staff nurse has a certain number of procedures and activities that, if successfully undertaken, indicates that you had a good day.

In a similar manner, as a physician you deal largely in quantitative outcomes as well; however, moving to the management billet of a physician leader, measuring your success will be more difficult, as you will begin to work with personalities and perceptions rather than measurable results. Consider that even the most important indicator of successful healthcare management performance—patient satisfaction—is very difficult to measure numerically and is definitely qualitative in scope.

Healthcare professionals deal with definite outcomes. For example, you either complete a laboratory analysis or not; fill a prescription correctly, or fail to note contraindications. Having clear-cut criteria provides a degree of satisfaction: You can recognize clearly the contribution you make toward providing stellar health care. Furthermore, this clarity of outcome provides a building block–like sequence, whereby you can improve your performance each day and compare it with a previous goal.

Healthcare management offers few black-and-white performance criteria. Given all the dynamics of change and expectations mentioned earlier in this chapter, it is very difficult to measure performance, clearly identify key performance criteria, and establish reliable goals for optimum performance. As a result, you must adapt your thinking to look at the breadth of activity, as opposed to the depth of activity. This means looking at the big picture as it relates to all of your department’s activities, establishing overall, comprehensive goals, and closely monitoring performance with an open mind—all without ever losing sight of the objective of providing excellent health care.

Certainly, this dimension of professional responsibility is not a new factor to your work life, as it is the guiding beacon for physician action. Accordingly, the initial decisions required in your role as a physician leader will be made with an already established frame of reference based on your professional experience to date. Numerous guidelines for making ethical decisions exist, but the following 7-step process offers a convenient, concise method for confronting ethical dilemmas.

In particular, the following process serves as a reminder that good decision making typically involves double checking before taking action. For example, the key issue in the checklist may well be Step 6, which requires you (and the organization you’re making decisions for) to essentially look in the mirror and evaluate the risk of public disclosure of your action and your willingness to bear it.

Step 1: Recognize the ethical dilemma.

Step 2: Get the facts.

Step 3: Identify your options.

Step 4: Test each option: Is it legal? Is it right? Is it beneficial?

Step 5: Decide which option to follow.

Step 6: Double-check your decision by asking two basic questions:

“How would I feel if my family found out about my decision?”

“How would I feel about this if my decision were printed in the local newspaper?”

Step 7: Take action.

Understanding Common Organizational Structures

Formally defined, organizing is the process of arranging people and other resources to work together to accomplish a goal. Organizing involves both dividing up the tasks to be performed and coordinating results to achieve a common purpose.

Figure 1–2 shows the role that planning and organizing, leading and managing, and command and control play in the management process. As the figure shows, managers are responsible for carrying out plans. Planning activities often precede organizing tasks, but the sequence varies based on the needs and culture of each healthcare organization (Chapter 5 covers the planning process in detail). Many beginning physician leaders will likely first follow long-standing plans and procedures that upper managers or former managers created before creating new plans of their own. Whatever the specifics of your situation, organizing and planning tasks often happen in close conjunction; be flexible and adjust your management duties to suit the situation.

At the most basic level, organizing includes

Implementing a clear mission, core values, objectives, and strategy

Identifying who is to do what, who is in charge of whom, and how different people and parts of the organization relate to one another

The challenge of organizing effectively is to choose the best form or structure to fit the demands of a given situation.

The organization structure is the system of tasks, workflow, reporting relationships, and communication channels that links the diverse parts of an organization. The specific structures vary greatly between healthcare organizations, but generally, any structure must both allocate or assign tasks and provide for the coordination of performance results.

Unfortunately, talking about good structures is easier than actually creating them. This is why you often read and hear about restructuring, the process of changing an organization’s structure in an attempt to improve performance.

Organization structures can be described and classified in several ways based on formality, function, divisions, and more.

You may know the concept of structure best in the form of an organization chart. A typical organization chart identifies, by diagram, key positions and job titles within an organization. It shows the lines of authority and communication between them.

An organizational chart shows the formal structure, the intended or official structure. The diagram depicts the way the organization is intended to function. Organizational charts can tell much about an organization, including

The division of work: Positions and titles show how work responsibilities are assigned.

Supervisory relationships: Lines among positions show who reports to whom.

Communication channels: Lines among positions show formal communication channels.

Major subunits: Positions reporting to a common manager are identified as a group.

Levels of management: Layers of management from top to bottom are shown.

However, behind every formal structure typically lies an informal structure. This is a shadow organization made up of the unofficial, but often critical, working relationships among organizational members. If you drew an organization’s informal structure, it would show who talks to and interacts regularly with whom, regardless of their formal titles and relationships. Informal structures include people meeting for coffee, exercise groups, friendship cliques, and many other possibilities. The lines of informal structures often cut across levels and move from side to side, rather than solely up and down.

Because of the complex nature of organizations and constantly shifting performance demands, informal structures can be very helpful in accomplishing large and small tasks. Through the emergent and spontaneous relationships of informal structures, people gain access to interpersonal networks of emotional support and friendship that satisfy important social needs. They also benefit from contacts with others who can help them better perform their jobs and tasks. Valuable learning and knowledge sharing take place as people interact informally throughout the workday and in a variety of unstructured situations.

Savvy organizations identify and capitalize on their informal structures. For example, a study by the Center for Workforce Development found that the cafeteria can be a “hotbed for informal learning,” as workers at a variety of levels tend to share ideas, problems, and solutions with one another over snacks and meals. Dynamic healthcare managers can mobilize these types of informal learning opportunities as resources for organizational improvement.

Of course, informal structures also have potential disadvantages. They can be susceptible to rumor, carry inaccurate information, breed resistance to change, and even divert work efforts from important objectives. People who feel left out of informal groupings may become dissatisfied.

Dividing Work Among Teams

Formally defined, a team is a small group of people with complementary skills who work together to achieve a shared purpose and who hold themselves mutually accountable for its accomplishment.

Teamwork is the process of people working together to accomplish these goals. The ability to lead through teamwork requires a special understanding of how teams operate and the commitment to use that understanding to help them achieve high levels of task performance and membership satisfaction. One of the biggest benefits of teamwork is synergy—the creation of a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. Synergy occurs when teams use their resources to the fullest and achieve through collective performance far more than is otherwise possible.

An important part of a manager’s job is to know when a team is the best organizing choice for a task. The second is to know how to work with and lead the team to best accomplish that task. The following section discusses the first task, using teams as an organizing tool for dividing work responsibilities.

While synergy is an important advantage, teams are useful in other ways. Being part of a team can have a strong influence on individual attitudes and behaviors. Working in and being part of a team can satisfy important individual needs and also improve performance. Teams, simply put, can be very good for both organizations and their members. Teams can be useful for a variety of reasons, including the following:

Increasing resources for problem solving

Fostering creativity and innovation

Improving the quality of decision making

Enhancing members’ commitments to tasks

Raising motivation through collective action

Helping control and discipline members

Satisfying individual needs as organizations grow in size

Of course, organizing based on a team approach is never a guaranteed success. Who hasn’t been part of a team that included members who slacked off because responsibility was diffused among several people and the rest of team would take care of the work? And who hasn’t heard people complain about having to attend what they consider to be another time-wasting meeting?

Fortunately, things don’t have to be this way. In fact, they must not be if teams are to make their best contributions to organizations. The following sections explore some of the most common types of teams in today’s workplace and recommends when each type of team is most appropriate.

Identifying Characteristics of Strong Teams

As a healthcare manager, establishing a team orientation is important in order to build a progressive work environment.

As a new healthcare manager, you are most likely inheriting a ready-made team. Your department may have been working together under the leadership of your predecessor. Even if you are forming a brand-new team, the following guidelines can help establish the standards you wish to incorporate into your team-building and team-orientation efforts. The following are key qualities consistent in all winning teams:

A motivated team attains its stated mission successfully and effectively. Motivation can come from a variety of sources, the first of which should be the department manager. Motivation can be positive, emphasizing encouragement, and progressive action, or negative, emphasizing less-than-satisfactory consequences due to failure to meet team objectives. Motivation also must come from the work group itself. Individuals must inspire one another to greater performance and support the efforts of all team members. Also, each team member must be self-motivated. Chapter 6 will provide more information on motivation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree