Low Anterior Resection: Hand-Assisted Laparoscopic Surgery Technique

Matthew G. Mutch

DEFINITION

The hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) technique uses a hand-assist device that allows the surgeon to insert his or her hand into the peritoneal cavity while maintaining pneumoperitoneum. The location of the hand port is variable and is placed at the expected site of specimen extraction.

HALS maintains all the short-term advantages of conventional surgery over open surgery.

By reintroducing tactile feedback into the field, HALS results in higher usage rates, lower conversion rates, and shorter operative times, when compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The main indication for a HALS low anterior resection is rectal cancer. Patients with diverticulitis with inflammation extending into the mesorectum may also require a low anterior resection.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history and physical examination are necessary prior to initiation of therapy for patients with rectal cancer.

It is important to identify the distance of the tumor from the anal verge. Digital rectal exam and rigid proctoscopy are used for this purpose and to determine whether the tumor is mobile, tethered, fixed, or involving the sphincter complex.

Prior abdominal surgery is not a contraindication to HALS approach. If the patient has had prior surgery, an incision can be made at the site of the hand port and if there are no or minimal adhesion, the hand port can be inserted. If the adhesions are prohibitive of the laparoscopic approach, the hand port incision can be extended into a full laparotomy incision.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

All patients with rectal cancer should have a complete colonoscopy prior to surgery. If the patient has an endoscopically obstructing lesion, a computed tomography (CT) colonography and contrast enema study are acceptable alternatives.

Preoperative staging of the tumor is paramount so the appropriate use of neoadjuvant therapy can be prescribed. This can be accomplished with either transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) or a rectal protocol magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Both studies have equivalent accuracy for determining the T and N stages, which are 80% and 60%, respectively. The TRUS is operator dependent and is limited to examining only those nodes adjacent to the tumor. MRI has the advantage of assessing the tumor encroachment of the mesorectal fascia.

Based on the preoperative T and N staging, the need for neoadjuvant radiation or chemoradiation therapy is determined. Typically, T3, T4, or N+ tumors receive neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy. Surgical resection then occurs 8 weeks after completion of neoadjuvant therapy.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Prior to taking the patient to the operating room, they should be marked for a possible diverting ileostomy. The patient needs to be assessed in the supine, sitting, and standing positions. The stoma should rest on the apex of skin fold and adequate distance from bony prominences, skin creases, and the waistline of their pants. The stoma should be brought through the rectus muscle to minimize the risk of developing a parastomal hernia.

The use of ureteral stents is left to the discretion of the surgeon.

Positioning

The use of a mechanical bed that is able to place the patient in the extremes of position is necessary.

There are many methods by which a patient can be secured to the bed. A beanbag, a nonslip pad, shoulder braces, or foam pads can be used for this purpose.

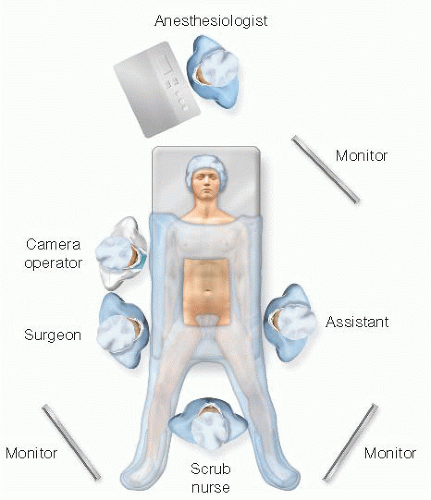

The patient should be placed in a modified lithotomy position with Allen or Yellofin stirrups (FIG 1). This allows access between the legs to assist with mobilization of the left colon and to the perineum for the anastomosis. The thighs

are placed parallel to the ground to avoid conflict with the surgeon’s elbows.

Both arms are tucked to the patient’s side with the thumbs facing up. This allows the surgeon, assistant, and camera driver plenty of room to maneuver during the case.

A monitor should be placed off the patient’s left shoulder during the mobilization of the left colon and splenic flexure. During the pelvic dissection, a monitor should be placed off the patient’s left foot for the surgeon and another should be placed off the patient’s right foot for the assistant.

TECHNIQUES

PORT PLACEMENT AND OPERATIVE TEAM SETUP

There are several options for the position of the hand port:

The hand port can be placed through either a Pfannenstiel or a midline incision. The suprapubic position allows for direct visualization into the pelvis. The hand port can then be used to facilitate the rectal dissection, for division of the distal rectum, for the performance of the anastomosis, and to address any pelvic complications such as bleeding or anastomotic failure.

The periumbilical position allows the surgeon to put his or her nondominant hand through the hand port.

A left lower quadrant (LLQ) position uses a musclesplitting incision and allows for the right hand to be placed into the abdomen to facilitate the lateral and splenic flexure mobilizations of the left colon.

For the purposes of this chapter, the suprapubic hand port position is discussed (FIG 2).

The 5-mm or 12-mm camera port is placed in the supraumbilical position. The camera needs to be above the umbilicus, as the wound protector portion of the hand port extends several centimeters beyond the edges of the incision.

The primary laparoscopic working port (12-mm port) is placed in the right lower quadrant (RLQ), at an equal distance between the hand port and the camera port and lateral to the rectus muscle.

A 5-mm working port for the first assistant is placed in the LLQ. This will allow the assistant to help with the lateral and splenic flexure mobilization and the pelvic dissection. The lower the port is placed, the less time the assistant works in a reverse motion to the camera during the lateral and splenic flexure mobilization.

The surgeon stands by the patient’s right side with his or her right hand placed in the hand port. The camera operator stands to the left side of the surgeon. The assistant stands by the patient’s left side (FIG 3).

TRANSECTION OF THE INFERIOR MESENTERIC ARTERY

The patient is placed in a steep Trendelenburg position and in airplane position with the left side up to use gravity to place the small bowel in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) and the omentum in the upper abdomen to expose the transverse colon and splenic flexure. This helps to expose the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) at its origin off the aorta and the inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) at the level of the ligament of Treitz.

The surgeon’s right hand is placed through the hand port and an energy source is placed through the RLQ working port.

The retroperitoneum is accessed at the level of the sacral promontory. The superior rectal artery is grasped and elevated (FIG 4). A wide incision is made in the peritoneum dorsal to this artery; the wider the incision, the more the artery can be more elevated to obtain better exposure. Because of the curve of the pelvis at this point, the sigmoid mesentery curves up and away from the visual field. Therefore, the retroperitoneal plane is higher than expected, so the more mobile the arterial pedicle is, the easier it is to visualize the correct plane.

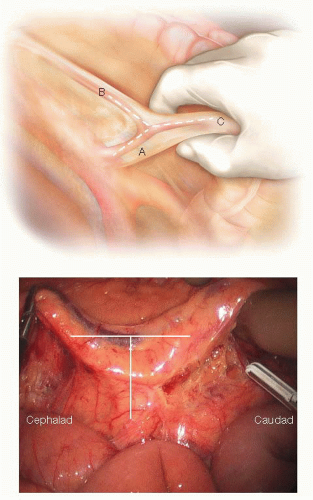

Identification of the left ureter is necessary before the IMA can be ligated (FIG 5). The following text is a fourstep algorithm to identify the left ureter.

Mobilization of the superior rectal artery is as described earlier and the ureter is identified.

At the level of the IMV: The IMV is grasped and elevated. The peritoneum is incised dorsal to the IMV and the retroperitoneum is accessed. The retroperitoneum is flat in this area and is often more easily accessed. Once in the correct plane, the dissection is carried in a caudad fashion to meet up with the initial plane under the superior rectal artery.

If the ureter is still not identified, the sigmoid and left colon is mobilized in a lateral to medial fashion.

Finally, the top of the hand port can be removed and the left ureter can be located via an open fashion.

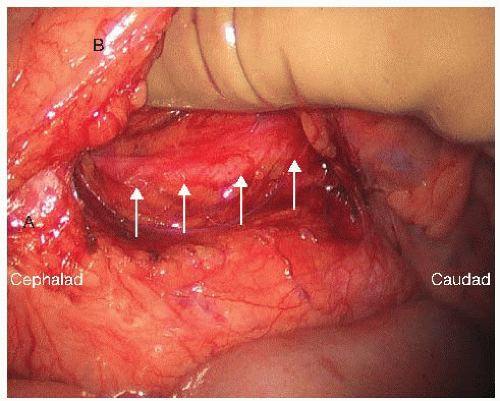

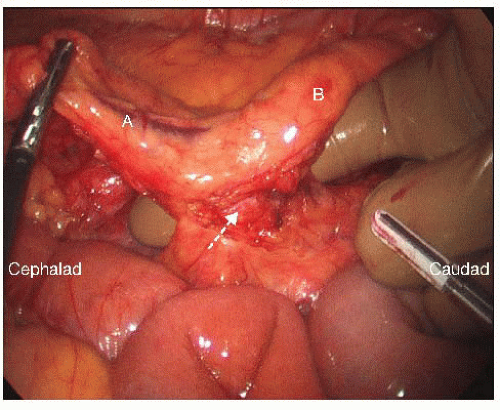

After the left ureter is identified and swept into the retroperitoneum, the IMA can be isolated at its origin (FIG 6). The index finger elevates the superior rectal artery and the middle finger is used to sweep down the retroperitoneum along the course of the IMA. This motion continues until the bare area is exposed cephalad to the IMA and medial to the IMV.

It is important to sweep down the retroperitoneal tissue in this area to help preserve the sympathetic plexus around the IMA. Once the IMA is safely isolated and the left ureter is clearly out of harm’s way, the vascular pedicle can be ligated at its origin from the aorta with the surgeon’s energy source of choice or with a linear stapler with a vascular cartridge (FIG 7).

FIG 6 • Circumferential dissection of the IMA. After the left ureter has been identified, the IMA (arrow) is circumferentially dissected at its origin of the aorta. Again, the “letter T” formed between the IMA and its terminal branches, the left colic artery (A) and the superior hemorrhoidal artery (SHA) (B) can be clearly identified.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|