Low Anterior Resection and Total Mesorectal Excision/Coloanal Anastomosis: Open Technique

Konstantinos I. Votanopoulos

Jaime L. Bohl

DEFINITION

Low anterior rectal resection (LAR) with total mesorectal excision (TME) is defined as the removal of the rectum en bloc with an intact perirectal fascial envelope distal to the cancer-bearing rectal wall. The visceral endopelvic fascia, also known as fascia propria or investing fascia of the mesorectum, is identified by a thin, loose areolar tissue that circumferentially separates the rectum and mesorectum from surrounding pelvic structures. Removal of the rectum with an intact mesorectum ensures complete removal of all lymph nodes and lymphatics that drain the diseased rectum without oncologic contamination of the pelvis at the time of surgery.

Coloanal anastomosis is the attachment of a mobilized proximal colon segment to the anal canal while preserving the anal sphincter musculature with a negative distal margin.

This operation is performed primarily for distal rectal cancer, when tumor location mandates rectal transection at the level of the pelvic floor (levator ani and puborectalis).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A detailed history should identify locally advanced rectal lesions that are causing bowel obstruction, bleeding, pseudodiarrhea, fecal incontinence, or excessive pelvic or anal pain. Nearly obstructed patients may require a temporary laparoscopic loop sigmoid colostomy prior to neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Patients with pain due to fixed tumors in the anal canal and sphincter are not candidates for coloanal anastomosis.

Prior colon and anorectal surgery, vascular surgery, or sphincter trauma during childbirth may have compromised the vascular supply to the planned colonic conduit or reduce the anal sphincter function.

Patients with poor functional status or poor fecal control prior to surgery are likely to have reduced quality of life and fecal soiling after surgery. These patients may be best served with a permanent colostomy rather than a sphincter-sparing coloanal anastomosis.

Digital rectal exam and rigid proctoscopy should be performed by the lead surgeon prior to the administration of neoadjuvant therapy. Anal sphincter, pelvic floor function, topography of rectal wall involvement, and distance of the distal aspect of the tumor from the dentate line determine the likelihood of sphincter salvage and method of reanastomosis. Submucosal tattooing distal to the rectal tumor identifies the location of clinically regressed tumors after neoadjuvant chemoradiation and is helpful for determining tumor clearance during pelvic dissection.

A detailed family history is necessary to identify risk of an inherited colon and rectal cancer syndrome as well as risk for metachronous colorectal cancer. We currently screen all young patients (<60 years of age) for Lynch syndrome and refer patients to genetic counseling when they have a positive screen or if they have multiple affected relatives.

Past medical history should identify patients with cardiopulmonary, liver, or kidney disease not medically suitable for a physiologically demanding operation.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A complete colonoscopy is obtained.

Preoperative staging with endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) determines the need for neoadjuvant chemoradiation. ERUS has a higher sensitivity and specificity for tumor depth rather than lymph node involvement as compared to MRI. MRI allows for assessment of the circumferential margin at the mesorectal envelope.1

Tumors located at the distal two-thirds of the rectum with greater than or equal to T3 wall invasion or greater than or equal to N1 nodal status will be referred for neoadjuvant treatment to decrease the risk of locoregional recurrence.2 Additionally, neoadjuvant therapy may lead to tumor shrinkage, increasing the likelihood of sphincter preservation while avoiding exposure of the small bowel, colonic conduit, and anastomosis to postoperative radiation. Postoperative radiation is associated with increased risk of anastomotic stricture and radiation enteritis.3

We routinely order a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis to evaluate for distant metastatic disease. Selected patients with liver metastases will be treated with a combination of staged resections and chemotherapy, whereas patients with synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis will be evaluated for cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Positron emission tomography (PET) for the initial staging of rectal cancer rarely alters disease management.4

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels are checked prior to the initiation of neoadjuvant chemoradiation, prior to resection and prior to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Patients undergo preoperative counseling and stoma marking by an enterostomal therapist. Counseling allows the patient to understand ostomy care, optimizes stoma placement, and reduces stoma-related complications.5

Placement of ureteral stents can facilitate ureteral identification in the setting of large rectal tumors, inflammation, previous surgery and pelvic radiation, and also contributes to intraoperative identification of ureteral injuries.

Bowel preparation or enema removes the mechanical obstacle of bowel contents in a narrow pelvis and reduces the tension on an infraperitoneal anastomosis.

Parenteral antibiotic prophylaxis covering bowel flora is given prior to surgical incision.

Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis via sequential compression devices (SCDs) and subcutaneous (SC) heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) prior to surgical incision is administered.

The surgical tray should include a lighted St. Mark’s retractor with the longest available blades, a big bite surgical energy device, and laparoscopic cautery and suction.

Positioning

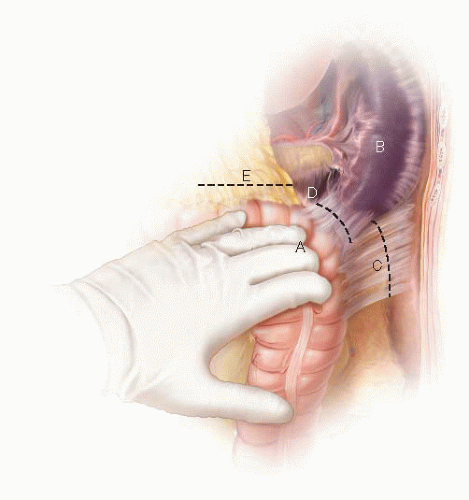

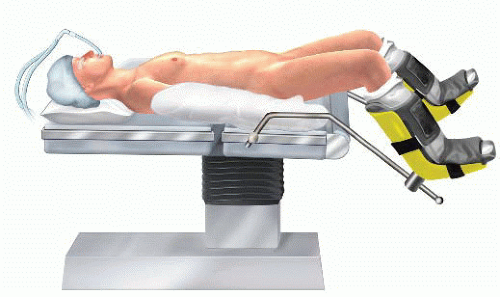

LAR with coloanal anastomosis requires access to both the pelvis and the perineum. Therefore, patients are placed in a lithotomy position with the hips slightly flexed and the knees completely flexed in Yellofin stirrups. Extra padding is applied on the fibular head and heels to prevent nerve injury and pressure ulcers. The buttocks are at the edge of the table with the tip of the coccyx accessible. The legs remain adducted during the pelvic dissection but will need to be abducted to allow perineal access during creation of the coloanal anastomosis (FIG 1).

FIG 1 • The patient is on a lithotomy position with the patient’s hips slightly flexed and the legs completely flexed in Yellofin stirrups. |

TECHNIQUES

LOW ANTERIOR RECTAL RESECTION WITH TOTAL MESORECTAL EXCISION

Incision, Abdominal Exploration, and Retraction of the Small Bowel

A laparotomy incision is made from the supraumbilical midline to the pubic bone. The fascia is opened between the rectus muscles. As the incision is opened to the level of the pubic bone, the bladder is mobilized to the left of the incision.

A careful exploration of the abdominal and pelvic cavity is undertaken to assess for distant metastatic disease and/or unresectable local disease. Attention should be given to the liver, retroperitoneum, aortic and external iliac lymph nodes, as well as peritoneal surfaces. Locally advanced disease may require a diverting colostomy followed by chemotherapy and radiation prior to resection.

A fixed abdominal retractor, such as a Bookwalter or Thompson retractor, is used for exposure. A laparotomy pad wrapped around the small intestine from the ligament of Treitz to the terminal ileum will prevent loops of small intestine from migrating into the operative field. A midline incision that barely extends above the umbilicus allows for tacking the small bowel under the right abdominal wall.

Mobilization of the Left and Sigmoid Colon, Colonic Mesentery, and Splenic Flexure

The left colon lateral attachments are incised with a cephalad direction. The areolar plane between the left colonic mesentery and the retroperitoneum is identified and opened. This plane is a few millimeters medial from the peritoneal reflection or white line of Toldt. Developing a plane at the exact edge of the white line of Toldt has the potential of lifting the retroperitoneal structures with subsequent ureteral and nerve injury.

The splenocolic, phrenocolic, and renocolic attachments are divided at the splenic flexure. In patients with difficult visualization, the transverse colon is retracted downward and the lesser sac is entered over the midtransverse colon by incising the gastrocolic ligament. Development of this plane in a medial to left lateral direction detaches the omentum from the distal transverse colon so that the medial and lateral planes of dissection can be joined to complete the splenic flexure mobilization (FIG 2).

The splenic flexure and proximal left colon mesentery are separated from the Gerota’s fascia. Incomplete mobilization of the splenic flexure results in a short colonic conduit and tension on the colorectal anastomosis, which could then lead to a postoperative anastomotic leak.

Vessel Ligation and Left Ureter Identification

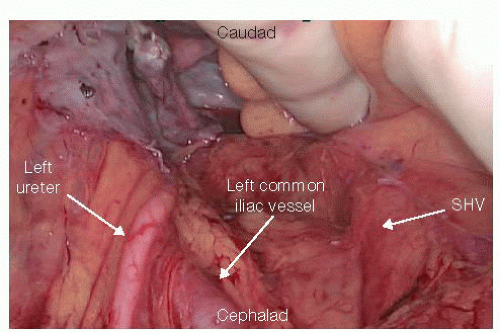

The separation of the left and sigmoid colon from the retroperitoneum is continued by reversing direction toward the pelvis. The left ureter is identified as it crosses over the left iliac artery and into the pelvis in a way that preserves the retroperitoneal location of the ureter but also identifies the areolar plane that medially extends to the superior hemorrhoidal vessels (SHV) arch (FIG 3). Lifting the mesosigmoid and placing the index finger behind the SHV arch allows the surgeon to incise with electrocautery the right surface of the peritoneum just under the dorsal surface of the SHV. This plane of dissection along the dorsal aspect of the SHV, as it is carried over the promontory, leads into the presacral tissue plane that will be later developed during the TME. At this

point, the mesentery is divided in between the sigmoid and descending colon, starting from the antimesenteric border. The SHV are ligated at the level of their origin from the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) in order to preserve the left colic pedicle intact. The colon itself is not divided. This prevents the colon from dropping into the dissection field during the operation and also allowing for any blood supply deficiencies in the proximal colon to manifest by the end of the dissection and prior to the anastomosis.

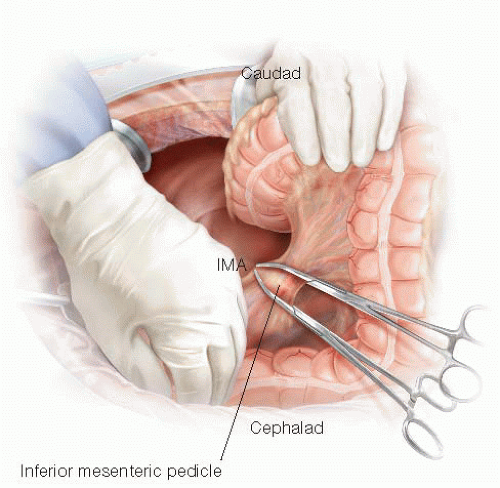

In cases of coloanal anastomosis, a high IMA transection at its takeoff from the aorta is usually performed, in an effort to prevent anastomotic tension (FIG 4). The collateral marginal artery that connects the middle colic artery and the IMA and runs close to the colon provides blood supply to the distal descending colon in these cases.

Reidentification of the ureter prior to IMA or SHV pedicle ligation ensures the left ureter is safe from injury.

Additional length of the colonic conduit can be achieved by ligating the inferior mesenteric vein just lateral to the ligament of Treitz.

FIG 4 • High IMA transection. In coloanal anastomosis cases, the IMA is transected at its origin between clamps in order to obtain maximal mobilization of the colonic conduit.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|