|

Typical Clinical Features |

Microscopic Features |

Ancillary Investigations |

Fat necrosis |

No typical features

Can be encountered in normal fat and in neoplasms with fat |

Fat with necrosis and many foamy macrophages, some multinucleated |

CD68+ in macrophages |

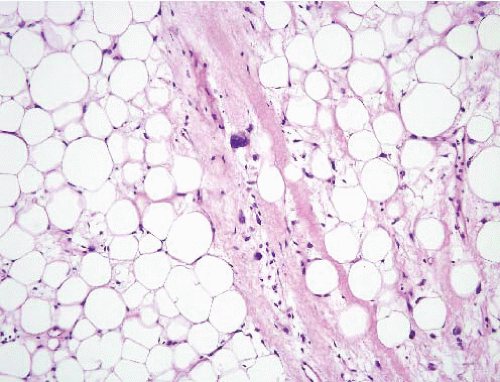

Fat atrophy |

Cachexia either from dieting, malignancy, or treatment for malignancy |

Lobulated fat with adipocyte shrinkage, capillaries appear more prominent |

Tumefactive extramedullary hematopoiesis |

Mass in patient with a myeloproliferative disorder, benign |

Trilinear hematopoiesis with erythroid hyperplasia and fat |

Lipoma with fat necrosis |

Usually superficial wellcircumscribed masses in adults (some intramuscular, rarely retroperitoneal) |

Has the appearance of mature fat

No hyperchomatic enlarged cells

Multinucleated histiocytes |

MDM2−, CDK4−, no MDM2 amplification, HMGA2 fusions |

Well-differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumor |

Deep tumors of adults >50 years |

Adipose tissue with scattered enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, often found in fibrous septa |

MDM2+, CDK4+−, MDM2 amplification |

Spindle cell liposarcoma/fibrosarcoma-like lipomatous neoplasm |

Deep or superficial axial tissues of adults, possibly slight male predominance, favorable prognosis |

Spindle cells, primitive fat cells |

Lack of MDM2 amplification, lack of DDIT3 rearrangements, controversy concerning loss of RB protein |

Lymphedema in the morbidly obese |

Large subcutaneous-based mass in obese individuals, often with overlying skin changes |

Dilated lymphatic channels, edema, mildly atypical fibroblasts |

MDM2−, CDK4−, no MDM2 amplification, HMGA2 fusions |

Myxoid liposarcoma, low- and high-grade |

Deep soft tissues of extremities of young adults

Often metastasizes to other soft tissue sites as well as to lungs |

Monotonous small uniform rounded cells with abundant (low-grade) or minimal (highgrade) myxoid matrix

Rich network of delicate vessels becomes inconspicuous in high grade form

Lipoblasts |

S100 protein+ in some cases, DDIT3-TLS or DDIT3-EWS rearrangements |

Pleomorphic lipoma |

Superficial lesion of shoulder girdle, neck of middle-aged adults, M > F |

Same features as spindle cell lipoma with the addition of enlarged atypical multinucleated cells (“fleurette” cells) and lipoblasts |

CD34+, S100 protein+ in fat, abnormalities of 13q and 16q, MDM2−, CDK4−, no MDM2 amplification |

Chondroid lipoma |

Multiple anatomic sites, adults |

Lobulated lesion with fat, “bubbly” cells, chondroid matrix, lipoblasts, hypovascular |

S100 protein+, balanced translocation t(11;16)(q13;p12-13), C11orf95-MLK2 fusion |

Silicone granuloma |

Often in breast associated with ruptured implant |

Infiltrates between lobules and ducts, macrophages |

CD68+ |

Myelolipoma |

Usually in the adrenal gland of adults, F > M, association with obesity, hypertension, and diabetes |

Mixture of fat and trilinear hematopoiesis without erythroid hyperplasia |

t(3;21)(q25;p11) shown in one case |

Hibernoma |

Adults usually younger than 40 years (younger than patients with ordinary lipomas), thigh |

Lobulated lesion with prominent capillaries, varying amounts of mature fat cells, cells with fine vacuoles and cells with granular eosinophilic cytoplasm |

Abnormalities of chromosome 11q13 |

Lipoblastoma |

Proximal extremities of infants, benign |

Lobulated with mature fat and areas with lipoblasts and numerous capillaries (that can be indistinguishable from myxoid liposarcoma) |

Variable S100 protein+, amplification of PLAG1, rearrangements of HAS2 or COL1A2 |

Myxofibrosarcoma |

Superficial lesions in elderly adults |

Richly vascular myxoid lesion with pleomorphic cells |

None useful in differential diagnosis

Often CD34+, actin+ |

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma |

Deep soft tissues of extremities, slight male predominance |

Uniform rounded cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm in hypovascular myxoid background |

S100 protein+, synaptophysin+, EWS-NR4A3 rearrangement |

Pleomorphic liposarcoma |

Deep soft tissue lesions in adults >50 years |

Pleomorphic lipoblasts in background that is either undifferentiated, epithelioid, or myxoid |

Can be CD34+, actin+, desmin+, focal S100 protein+

MDM2−, CDK4− |

Dedifferentiated liposarcoma |

Deep tumors of adults >50 years, typically retroperitoneal |

Areas of atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma and juxtaposed zones of pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma |

MDM2+, CDK4+/−, MDM2 amplification |

Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma |

Deep neoplasms in adults >50 years, usually proximal thigh |

Pleomorphic spindle cell neoplasm with cells with markedly eosinophilic cytoplasm |

Desmin+, myogenin+ (nuclear), MyoD1+ (nuclear) |

Pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma (malignant fibrous histiocytoma) |

Deep neoplasms in adults >50 years, usually proximal thigh |

Pleomorphic spindle cell neoplasm, often with storiform pattern |

Variable actin, desmin, MyoD1−, MDM2−, CDK4− |

Pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma |

Adults >50 years, deep extremities |

Defined as pleomorphic zones comprising two-thirds of the tumor, typical leiomyosarcoma in the remainder with fascicles of brightly eosinophilic cells with blunt-ended nuclei and paranuclear vacuoles |

Actin+, desmin+, calponin+, caldesmon+, myogenin−, MyoD1−, focal keratin in some cases |