Left Hemicolectomy: Hand-Assisted Laparoscopic Technique

Steven A. Lee-Kong

Daniel L. Feingold

DEFINITION

Left hemicolectomy is typically defined as resection of the splenic flexure of the colon with its mesentery including the left colic artery and the left branch of the middle colic artery. This operation is most commonly performed for neoplasia and is, in general terms, a mirror image of a right colectomy whereby the colon is mobilized and the mesentery is dissected out and transected, allowing exteriorization of the loop of colon. During left colectomy for cancer, the left side of the greater omentum is usually resected en bloc with the colon. The straight laparoscopic approach to splenic flexure lesions can be challenging, especially in cases with a large neoplasm, colonic obstruction, or difficult splenic flexure (“extreme” flexure). In these circumstances, the hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) approach to left colectomy may prove advantageous over a pure laparoscopic approach as it restores tactile sensation and improves retraction and exposure.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Prior surgical history can influence the approach to left colectomy

Prior colon resection

May affect remaining colonic blood supply and can influence the operative plan regarding what bowel segment will be used for the anastomosis

Extensive intraabdominal surgery

Extensive or dense adhesions may prohibit a minimally invasive approach.

Prior gastric or bariatric surgery can distort the anatomy and make for challenging dissection for left colectomy.

Abdominoplasty

May limit intraabdominal domain afforded by the pneumoperitoneum

Morbid obesity or an abundance of intraabdominal adipose tissue may hinder a minimally invasive approach.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging of the abdomen and pelvis is useful for planning the surgery in terms of accurate localization and in determining the site of the hand port. Imaging can also alert the surgeon of a potentially difficult splenic flexure takedown (extreme flexure, significant colon looping, bulky colon neoplasia adjacent to the spleen, etc.).

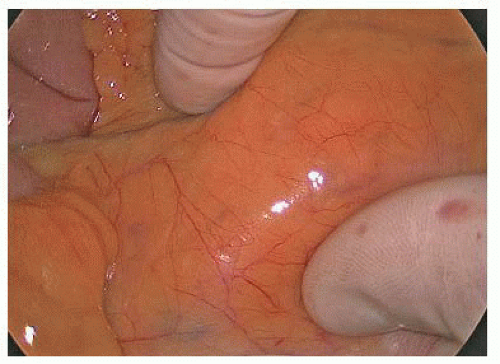

Colonoscopy to evaluate the remaining colon. In addition, it allows to localize the target lesion with tattoos which is useful and facilitates a laparoscopic approach.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Colonoscopy and pathology reports and relevant crosssectional imaging should be reviewed.

Intraoperative carbon dioxide (CO2) colonoscopy should be available in the operating room for localization purposes (if necessary) as well as for assessment of the anastomosis, if needed.

Mechanical bowel preparation facilitates intraoperative colonoscopy in cases where preoperative localization fails.

In cases of neoplasia, the operative plan should be to perform a cancer operation regardless if the colonoscopy biopsies fail to demonstrate malignancy.

Positioning

For HALS left colectomy, the authors prefer to use padded split-leg position with Ace wraps, securing the patient’s legs to the operating room table (FIG 1). This allows the surgeon to stand between the patient’s legs during the procedure. Split-leg positioning may be preferable to stirrups as the legs are maintained in a neutral position and pressure-related nerve injuries are minimized.

The patient should be secured to the operating room table with a chest strap, as extreme positioning is often necessary.

The right arm should be padded and tucked in a neutral position.

FIG 1 • Patient positioning. We prefer a split-leg position to allow the surgeon to operate from between the legs and to minimize potential leg injuries. |

TECHNIQUES

ENTERING THE ABDOMEN AND INITIAL EXPOSURE

A Pfannenstiel or lower midline incision is created for hand-port placement (FIG 2). A 5-mm camera port is placed in the supraumbilical midline and 5-mm working ports are placed in the right lower quadrant and left lower quadrant positions.

In patients with prior abdominal surgery, laparoscopic access can be created by cut-down or Veress needle technique in a presumed safe location. This allows laparoscopic evaluation of abdominal wall adhesions, which can be lysed prior to creating the hand-port access. Alternatively, adhesions can be lysed in an open fashion through the hand-port incision; the surgeon’s ability to perform adhesiolysis in this fashion may be limited. Inability to lyse these adhesions can jeopardize the laparoscopic approach.

The patient is placed in steep Trendelenburg with the table tilted right side down.

The greater omentum is draped over the transverse colon and liver. The small bowel is retracted out of the pelvis and toward the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, exposing the sigmoid and left colon mesentery (FIG 3).

A laparotomy pad placed intraabdominally through the hand port aides in the retraction of the small bowel and in maintaining exposure. This also facilitates cleaning the scope without having to remove the scope from the abdomen. To reduce the chance of a retained pad, a hemostat is placed on the surgeon’s gown, signifying that a pad is in the belly. When the pad is removed (typically just prior to extraction), the hemostat is removed from the gown. If the surgeon goes to remove his or her gown with the hemostat still in place, the team is alerted that there may be a retained foreign body in the patient.

A 30-degree angled scope is used at the discretion of the surgeon. Angled scopes enable the surgeon to look over the horizon (particularly useful in splenic flexure takedown) and improves laparoscopic access to the field by allowing the scope to be held away from the dissection.

MESENTERIC DISSECTION, MEDIAL TO LATERAL

Commonly, the sigmoid and its mesentery are mobilized in order to permit extraction and the creation of a tension-free anastomosis. In cases where this degree of mobilization is not required, these steps may be omitted.

The surgeon stands at the patient’s right hip and the assistant stands at the right shoulder holding the camera at the umbilicus. The inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) pedicle is elevated with the surgeon’s right thumb and index finger (FIG 4) and is retracted toward the patient’s left hip. The surgeon uses an energy device through the right lower quadrant port to dissect dorsal to the IMA and its superior hemorrhoidal terminal branch (FIG 5). The aortic bifurcation and common iliac arteries are appreciated prior to starting the dissection. The peritoneum beneath the pedicle is scored to the level of the sacral promontory.

Palpating the right and left common iliac arteries located underneath the mesosigmoid and over the sacral promontory orients the surgeon (FIG 6).

Care is taken to preserve the hypogastric nerves located dorsal to the superior hemorrhoidal vessels.

The retromesenteric plane is developed by sweeping the retroperitoneum down (dorsally) and elevating the mesentery (FIG 6). The plane is developed laterally toward the side wall, superiorly over Gerota’s fascia and caudally toward the presacral space. As this is a relatively bloodless plane of dissection, bleeding is usually caused by injury to the overlaying mesentery or dissection into the floor of the space that is the retroperitoneum. Recognizing that you are not in the actual embryonic fusion plane allows you to adjust the dissection and reenter the correct plane.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree