Laryngoscopy and Endotracheal Intubation

Laura A. Adam

Kent Choi

Laryngoscopy, or visualization of the larynx, is performed for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. In this chapter, indirect (or mirror) laryngoscopy and the direct laryngoscopy for the purpose of endotracheal intubation are discussed. The use of the fiberoptic laryngoscope is described as part of fiberoptic bronchoscopy (see Chapter 25).

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified endotracheal intubation as an “ESSENTIAL COMMON” procedure.

STEPS IN INDIRECT LARYNGOSCOPY

Obtain adequate topical anesthesia

Warm the mirror to avoid fogging

Introduce the mirror into back of oropharynx

STEPS IN ENDOTRACHEAL INTUBATION

Positioning the patient

Placing the patient in the sniffing position when possible

Providing cervical spine stabilization when necessary

Inducing appropriate sedation and relaxation

Introducing the laryngoscope blade

Advancing a straight (Miller) blade over the epiglottis

Advancing a curved (Macintosh) blade in front of the epiglottis

Lifting the larynx gently in the anterior caudal direction

Visualizing the laryngeal aperture

Passing the endotracheal tube through cords

Confirming endotracheal placement of tube

Securing in place

Obtaining a chest x-ray to verify appropriate positioning

ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Oral trauma

Tracheal stenosis

Esophageal intubation

Right mainstem bronchial intubation

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Tongue

Uvula

Pharynx

Nasopharynx

Oropharynx

Laryngopharynx (hypopharynx)

Palatoglossal arch

Hyoid bone

Hyoepiglottic ligament

Larynx

Laryngeal inlet

Epiglottis

True vocal cords

Vestibular folds (false vocal cords)

Rima glottidis, glottis

Arytenoid cartilages

Cuneiform and corniculate cartilages

Interarytenoid notch

Hyoepiglottic ligament

Trachea

Cricoid cartilage

Thyroid cartilage

Carina

Indirect Laryngoscopy

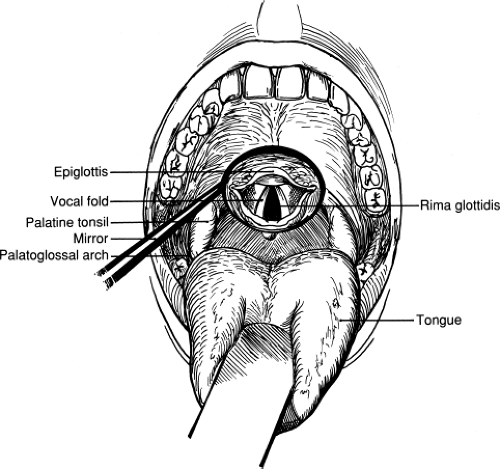

Mirror Laryngoscopy (Fig. 2.1)

Technical Points

The patient should be seated facing the examiner for this procedure. Adequate topical anesthesia of the posterior pharynx is essential. Ask the patient to open the mouth and stick out the tongue. Spray a topical anesthetic over the tongue, soft palate, uvula, and posterior pharynx. Gently grasp the tongue with a dry sponge or deflect it down with a tongue blade to improve visibility. Use a headlamp to provide illumination. Warm a dental mirror by holding it under hot running water so that it does not fog when placed in the warm, moist environment of the posterior pharynx. Use your nondominant hand to apply posterior pressure to the thyroid cartilage to increase visualization.

Place the mirror in the oropharynx, just anterior to the uvula. Push back gently on the uvula and visualize the larynx by adjusting the angle of the mirror slightly (Fig. 2.1). Observe the vocal cords for color, symmetry, abnormal growths, and mobility during phonation. The mirror can also be used to inspect the lateral pharyngeal wall and can be reversed to view the posterior nasopharynx.

Recognize that the mirror produces an apparent reversal of anterior and posterior regions. Visualization of the anterior commissure and base of the epiglottis and the subglottic regions is limited by overhanging structures.

Anatomic Points

The upper aerodigestive tract is divided into the oral cavity proper and the pharynx on the basis of embryologic origin. The oral cavity is lined by epithelium of ectodermal origin. It ends at about the level of the palatoglossal arch. The pharynx is lined with epithelium that is endodermally derived. It is divided into the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx. The nasopharynx is posterior to the nose and superior to the soft palate. The oropharynx extends from the soft palate to the hyoid bone. The laryngopharynx extends from the hyoid bone to the cricoid cartilage and is also known as the hypopharynx.

The larynx is made of a combination of skeletal structures, muscles, and connective tissues, and is responsible for phonation, assistance with respiration, and protection against aspiration. At the superior aspect of the larynx is the hyoid bone which during swallowing elevates the larynx via the hyoepiglottic ligament to prevent aspiration. The epiglottis along with the thyroid, cricoid, and arytenoid cartilages make up the skeletal portion of the larynx. The thyroid cartilage is attached to the epiglottis and forms the externally prominent Adam’s apple. The cricoid cartilage is also a single cartilage and is the only complete cartilage. The posterior cartilages are paired and consistent of the arytenoid, the cuneiform, and corniculate cartilages. During laryngoscopy, the vocal cords are encircled posteriorly from lateral to medial by the paired structures of the aryepiglottic folds, cuneiform cartilages, and corniculate cartilages where they fuse at the interarytenoid notch. This is the most posterior portion of the laryngeal inlet and must be viewed for endotracheal intubation. The lateral mucosal folds known as the vestibular folds (false vocal cords) are covered by respiratory epithelium and are responsible for resonance. The true vocal cords via posterior attachments to the arytenoids and anterior attachments to the thyroid and cricoid cartilages are

responsible for phonation. The opening that is viewed between them is known as the rima glottidis whereas the glottis is the vocal cords and the space between them.

responsible for phonation. The opening that is viewed between them is known as the rima glottidis whereas the glottis is the vocal cords and the space between them.

Endotracheal Intubation

Positioning the Patient (Fig. 2.2)

Technical Points

Position the patient supine with the neck slightly flexed and a small roll under the head. Stand at the head of the operating table or bed. If you are intubating a patient in bed, remove the headboard whenever possible to gain better access to the patient.

The “sniffing position” (Fig. 2.2A) decreases the distance from the teeth to the larynx and facilitates visualization of the larynx. Hyperextension of the neck (Fig. 2.2B) increases the distance from the teeth to the larynx and makes intubation more difficult. Flexion of the head on the neck compresses the airway, again making intubation more difficult. Achieve the correct position by placing a small pillow or folded sheet under the head.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree