Laryngoscopy and Endotracheal Intubation

Laryngoscopy, or visualization of the larynx, is performed for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. In this chapter, indirect (or mirror) laryngoscopy and the visualization of the larynx for the purpose of endotracheal intubation are discussed. The use of the fiberoptic laryngoscope is not presented here because visualization of the upper airway using this instrument is similar to that described for fiberoptic bronchoscopy (see Chapter 24).

Steps in Indirect Laryngoscopy

Adequate topical anesthesia

Warm the mirror to avoid fogging

Gently introduce into back of oropharyns

Steps in Endotracheal Intubation

Sniffing position

C-spine stabilization if trauma

Adequate relaxation

Straight blade goes over the epiglottis

Curved blade goes in front of the epiglottis

Gentle pressure toward the spine may be needed

Pass Tube through Cords under Direct Visualization

Presence of CO2 confirms position in trachea

Secure in place

Chest x-ray to verify position

Anatomic Complications

Esophageal intubation

Right mainstem bronchus intubation

List of Structures

Larynx

Laryngeal inlet

Rima glottides

Thyroid cartilage

Vestibular folds

Tongue

Uvula

Epiglottis

Hyoid bone

Hyoglossus muscle

Hyoepiglottic ligament

Trachea

Cricoid cartilage

Carina

Pharynx

Nasopharynx

Oropharynx

Laryngopharynx

Palatine tonsil

Palatoglossal arch

Indirect Laryngoscopy

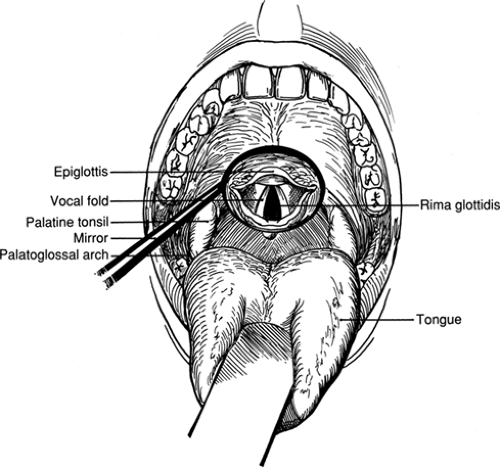

Mirror Laryngoscopy (Fig. 2.1)

Technical Points

The patient should be seated facing the examiner for this procedure. Adequate topical anesthesia of the posterior pharynx is essential. Ask the patient to open the mouth and stick out the tongue. Spray a topical anesthetic over the tongue, soft palate, uvula, and posterior pharynx. Gently grasp the tongue with a dry sponge or deflect it down with a tongue blade to improve visibility. Use a headlamp to provide illumination. Warm a dental mirror by holding it under hot running water so that it does not fog when placed in the warm, moist environment of the posterior pharynx.

Place the mirror in the oropharynx, just anterior to the uvula. Push back gently on the uvula and visualize the larynx

by adjusting the angle of the mirror slightly (Fig. 2.1). Observe the vocal cords for color, symmetry, abnormal growths, and mobility during phonation. The mirror can also be used to inspect the lateral pharyngeal wall and can be reversed to view the posterior nasopharynx.

by adjusting the angle of the mirror slightly (Fig. 2.1). Observe the vocal cords for color, symmetry, abnormal growths, and mobility during phonation. The mirror can also be used to inspect the lateral pharyngeal wall and can be reversed to view the posterior nasopharynx.

Recognize that the mirror produces an apparent reversal of anterior and posterior regions. Visualization of the anterior commissure and base of the epiglottis, the ventricles, and the subglottic regions is limited by overhanging structures.

Anatomic Points

The upper aerodigestive tract is divided into the oral cavity proper and the pharynx on the basis of embryologic origin. The oral cavity is lined by epithelium of ectodermal origin. It ends at about the level of the palatoglossal arch. The pharynx is lined with epithelium that is endodermally derived. It is divided into the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx. The nasopharynx is posterior to the nose and superior to the soft palate. The oropharynx extends from the soft palate to the hyoid bone. The laryngopharynx extends from the hyoid bone to the cricoid cartilage.

Endotracheal Intubation

Positioning the Patient to Straighten and Shorten the Airway before Intubation (Fig. 2.2)

Technical Points

Position the patient supine with the neck slightly flexed and a small roll under the head. Stand at the head of the operating table or bed. If you are intubating a patient in bed, remove the headboard whenever possible to gain better access to the patient.

The “sniffing position” (Fig. 2.2A) decreases the distance from the teeth to the larynx and facilitates visualization of the larynx. Hyperextension of the neck (Fig. 2.2B) increases the distance from the teeth to the larynx and makes intubation more difficult. Flexion of the head on the neck compresses the airway, again making intubation more difficult. Achieve the correct position by placing a small pillow or folded sheet under the head.

Do not manipulate the head and neck in a patient with a known or possible cervical spine injury. Displacement of vertebrae can cause irreversible damage to the spinal cord. In the situation of known or suspected injury to the cervical spine, fiberoptic laryngoscopy, blind nasotracheal intubation (generally only successful in breathing patients), or cricothyroidotomy is safer than orotracheal intubation. These difficult airway problems are discussed in the references.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree