Laparoscopy: Principles of Access and Exposure

Laparoscopic surgery requires intense attention to the details of the equipment used. Become familiar with the equipment used in your operating room. Ensure that it is in working order and that the supplies that you will need for the procedure are at hand or readily available. An equipment troubleshooting chart, such as that produced by Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) (referenced at the end), can be invaluable when problems arise.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified diagnostic laparoscopy as an “ESSENTIAL COMMON” procedure.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE

Position patient and monitor

Surgeon should stand opposite site of pathology (operative field)

Primary monitor is placed directly across from surgeon

Choose entry site

Closed entry

Make a small incision at entry site

Lift fascia

Pop Veress needle into peritoneal space (usually two pops are felt)

Aspirate and confirm absence of blood or succus

Saline should flow freely

Drop of saline in hub of needle should be sucked into peritoneum

Insufflate to desired pressure

Open entry with Hasson cannula

Make minilaparotomy incision and enter peritoneum

Place sutures on each side of peritoneal/fascia incision

Insert trocar and laparoscope

Inspect abdomen

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Injury to bowel during initial entry

Injury to retroperitoneal vessels during entry

Poor choice of trocar sites, room setup, causing difficulty with subsequent procedure

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Linea alba

Rectus abdominis muscle

Umbilicus

Median umbilical fold (urachus)

Falciform ligament

Inferior epigastric artery and vein

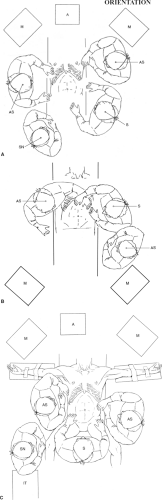

Patient positioning and layout of equipment can facilitate a laparoscopic procedure or immensely complicate it. Locate the primary monitor directly opposite the surgeon in a straight line of sight. Figure 46.1A shows the typical setup for surgery in the right upper quadrant (laparoscopic cholecystectomy, plication of perforated ulcer, liver biopsy or similar procedures). A secondary monitor may be located across from the first assistant, who will generally stand on the opposite side of the table. Arrange the insufflator, light source, cautery and other energy sources, suction irrigator, and so on, and the associated cords in such a fashion that you are free to move from one side of the table to the other if necessary.

For lower abdominal procedures, such as laparoscopic appendectomy (Chapter 95), it is best to tuck the arms at the side. This allows the surgeon and first assistant to move as far cephalad as needed without being cramped by the arm boards (Fig. 46.1B). Gynecologic laparoscopists will generally place the patient in stirrups to allow manipulations from below, for example, elevating the cervix to enhance visualization of the pelvic organs (see Figure 104.2A in Chapter 104).

Advanced laparoscopic procedures performed around the esophageal hiatus, such as laparoscopic fundoplication (Chapter 53) or esophagomyotomy (Chapter 55) are also best performed with the patient’s legs spread to enable the surgeon to stand between the legs (Fig. 46.1C). This provides the straightest possible line of sight to the operative field and enables two assistants to stand comfortably, one on each side. Further information is given in the chapters for specific procedures.

References at the end give additional information about equipment setup and troubleshooting.

References at the end give additional information about equipment setup and troubleshooting.

Access to the Abdomen—Closed, with Veress Needle (Fig. 46.2)

Technical Points

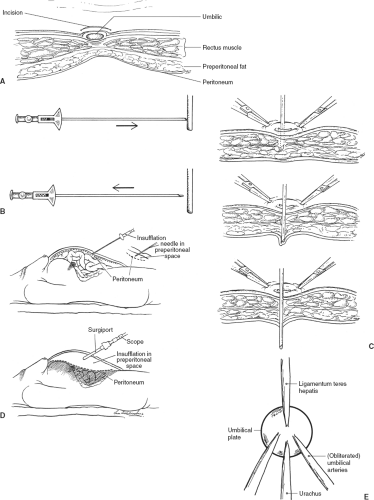

The umbilicus is the usual site of initial entry. An infraumbilical “smile” or supraumbilical “frown” incision made in a natural skin crease is virtually invisible when healed (Fig. 46.2A). If conversion to open laparotomy is a strong possibility, a vertically oriented circumumbilical incision gives equally good access and is easily incorporated into a vertical midline incision.

Visualize the probable site of the pathology within the abdomen and consider the location of the umbilicus relative to this site. The level of the umbilicus varies considerably from individual to individual—do not hesitate to make the entry site slightly above or below the umbilicus, if necessary. If the umbilicus is low on the abdomen and the target site is in the upper abdomen, an incision above the umbilicus may be necessary. Conversely, an incision below the umbilicus may provide the best visualization for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a small patient. If all other things are equal, it is a bit easier to enter the abdomen through a smile incision because this avoids the falciform ligament. Make the incision a millimeter or two longer than the diameter of the trocar you plan to use. Deepen the incision through skin and subcutaneous tissue until the fascia at the base of the umbilicus is encountered. If the patient is obese, place a Kocher clamp on the underside of the umbilicus and pull up. Because skin is adherent to fascia at the umbilicus, this will elevate the fascia. Place Kocher clamps side by side on the fascia. Hold one in your nondominant hand and have your first assistant hold the other.

Test the Veress needle and confirm that the tip retracts easily (Fig. 46.2B). Introduce the Veress needle with steady controlled pressure, attentive to the popping sensations as it passes through the fascia and then the peritoneum (Fig. 46.2C). When the Veress needle is properly positioned, the tip should move freely from side to side as the hub is gently moved back and forth.

Attach a syringe filled with saline. Aspirate, observing for gas, blood, or succus entericus. If the needle is properly positioned, a vacuum will be created. Inject saline; there should be no resistance to injection. Leave a meniscus of saline within the hub of the needle when you remove the syringe. Elevate both Kocher clamps while observing the meniscus. The saline should be drawn into the abdomen by the negative pressure thus created, confirming proper intraperitoneal positioning of the needle. Insufflate the abdomen. It is extremely important to take the time to ascertain proper placement to avoid visceral injury. On the other hand, if the Veress needle is not deep enough, the preperitoneal space can absorb an amazing amount of CO2, making subsequent entry into the abdomen more difficult (Fig. 46.2D).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree