Laparoscopic Transverse Colectomy

Govind Nandakumar

Sang W. Lee

DEFINITION

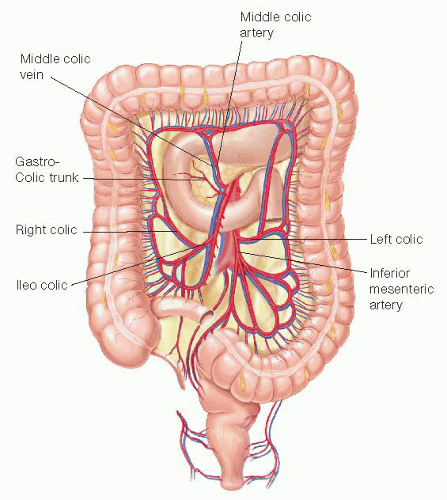

Transverse colectomy refers to removal of the portion of the colon between the hepatic flexure and the splenic flexure— the transverse colon. This portion of the colon derives its blood supply from the right and left branch of the middle colic vessels in addition to collateral flow from the ileocolic, right colic, and left colic vessels. Transverse colectomy is commonly performed for tumors and/or polyps of this region. An alternative approach to these tumors is to perform an extended right or extended left colectomy. This chapter focuses on laparoscopic transverse colectomy.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A complete history and physical focusing on the underlying pathology is essential. For patients with colon cancer and/or polyps, a detailed surgical history, personal cancer history, and family history is essential.

Preoperative genetic counseling and testing may be indicated based on age and family history.

Presence of an inherited cancer syndrome such as familial adenomatous polyposis or hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome may require a total colectomy rather than a transverse colectomy.

Prior abdominal surgery, distension, and obstruction are important to elicit in the history and physical examination prior to making a decision regarding open versus laparoscopic approach.

History or physical examination suggestive of focal abdominal pain and tenderness are suggestive of abdominal wall invasion and more extensive or open surgical approach may be needed.

History and physical examination should also evaluate the cardiovascular and respiratory systems to assess the ability to tolerate pneumoperitoneum.

Nutritional status and recent history of major weight loss should be considered in performing primary anastomosis.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

All patients with colon cancer and/or a polyp should have a complete extent of disease workup including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvic, chest X-ray, colonoscopy, and routine preoperative testing.

The CT should be reviewed carefully to assess adjacent organ involvement, metastatic disease, and obstructive disease.

Laparoscopic approach may not be feasible in the presence of massive distension and obstruction.

Large bulky tumors with a tethered mesentery or adjacent organ involvement may also preclude laparoscopy.

Colonoscopy and evaluation of the entire colon is important to ensure there are no synchronous lesions proximal or distal to the area of resection.

For small nonobstructing lesions, endoscopic tattoo marking should be performed prior to surgery.

Endoscopic tattooing should be performed just distal to the tumor and in three quadrants.

In general, tumors that are identified on CT scan can be readily identified laparoscopically and do not require a tattoo.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

The patient receives a mechanical bowel preparation to facilitate handling of the colon and to facilitate intraoperative colonoscopy if required. The need for bowel preparation is controversial. The consequences of a leak may be more significant without preparation. Laparoscopic handling of the colon is easier after mechanical bowel preparation.

The patient is seen and evaluated by the surgical and anesthesia teams in the preoperative area on the day of surgery.

Most patients are offered and elect to have an epidural or intravenous catheter for patient-controlled anesthesia.

A second- or third-generation cephalosporin or ertapenem is used for antibiotic prophylaxis within 1 hour of skin incision and redosed as needed. No antibiotics are administered postoperatively.

Venodyne boots and 5,000 units of subcutaneous heparin are used for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

Positioning

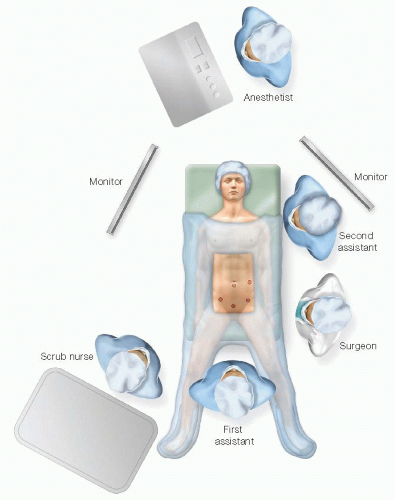

The patient is positioned in a modified lithotomy position with both arms tucked to the sides. It is essential to ensure that all pressure points, fingers, and calves are padded adequately.

Use of a beanbag and cloth tape allows extreme positioning with decrease in possibility of patient sliding.

Alternatively, use of gel pads commonly available in the operating room (OR) makes routine taping of patient not necessary.

Use of shoulder braces should be avoided as they can cause brachial plexus injury.

Prior to draping, the patient is placed in steep Trendelenburg and the table is rotated to ensure that the patient is secured well.

It is essential to ensure that both knees are in line with the torso in order to avoid collision of instruments to patient’s thighs when working in the upper quadrants of the abdomen. The abdomen is prepped from the nipples to the midthigh.

Access to the anus is always maintained for possible intraoperative colonoscopy.

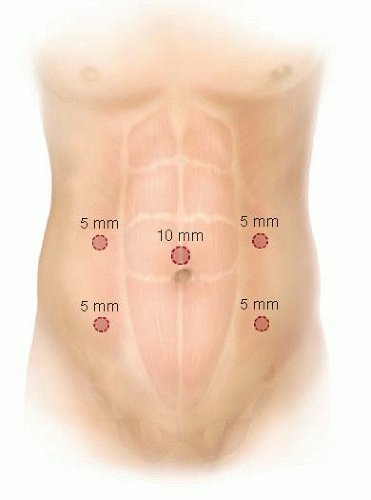

FIG 1 (laparoscopic setup) shows the OR setup for this procedure. Monitors are placed over the shoulders of the patient so that the surgeon, pathology, and monitors are situated in line.

FIG 1 • Illustrates the patient setup. A modified lithotomy position allows the surgeon or assistant to stand between the legs and to have access to the anus for intraoperative colonoscopy. |

TECHNIQUES

SKIN INCISIONS

A Hasson technique is used to achieve access to the abdomen at the umbilicus.

Four 5-mm trocars are placed—two on either side of the abdomen lateral to the rectus with one hand breadth between the trocars. An optional fifth trocar can be placed in the suprapubic area if required for retraction. FIG 2 (trocars) shows the typical trocar placement.

LAPAROSCOPIC EXPLORATION

The abdomen is systematically explored in all four quadrants to look for metastatic disease and/or unexpected pathology.

Knowledge of the mesenteric anatomy is essential for a successful laparoscopic approach.

FIG 3 (colon anatomy) shows the colon with its major vascular pedicles. Also depicted is the gastrocolic trunk of Henle that can be a source of bleeding if not recognized during the dissection.

The right colic vessels commonly originate from the ileocolics (85%).

The middle colic arteries commonly have more than two branches (55%).

PEDICLE LIGATION

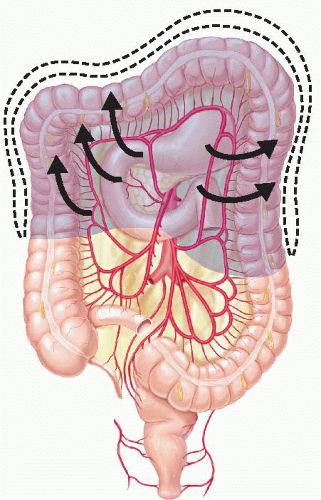

The ileocolic, middle colic, and left colic vessels are first identified (FIG 4). Identification of the vascular pedicles is facilitated by traction on the colon to tent the mesentery. Adequate exposure is achieved by grasping each flexure and retracting superiorly and laterally (FIG 5).

A window is created in the colon mesentery between the ileocolic and middle colic vessels. With appropriate traction and countertraction, the retromesenteric dissection is continued superiorly, medially, and laterally into the lesser sac (FIG 6).

Care is taken to protect the duodenum, head of the pancreas, and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and vein during the dissection.

The middle colic vessels can be divided at the common trunk or divided individually after bifurcation (FIG 7). There is significant variation in the anatomy of the middle colic trunk.

Our practice is to use a bipolar vessel-sealing device to divide the pedicles, but clips and staplers are also options to divide the pedicles. It is important to ensure that the SMA and vein are protected and that sufficient cuff of the vascular pedicle is retained to control bleeding should the vessel sealers fail.

Strong anterior traction on the transverse colon mesentery optimizes middle colic dissection and decreases the likelihood of inadvertent injury to SMA.

FIG 4 • Appropriate traction on the colon in the direction of the arrows exposes the mesentery and allows for identification of the major vascular pedicles. |

FIG 5 • Cephalad and lateral traction is used to visualize the middle colic vessels.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|