Laparoscopic Retroperitoneal Adrenalectomy

Michael G. Johnston

James A. Lee

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this presentation are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States government. Michael G. Johnston is a military service member (or employee of the U.S. Government). This work was prepared as part of his official duties. Title 17, USC, §105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government.” Title 17, USC, §101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties.

INDICATIONS

Adrenalectomy is indicated for a variety of different clinical scenarios, including patients with (1) a functional tumor; (2) a solid adrenal mass larger than 3 to 4 cm, due to increasing risk of adrenocortical carcinoma; (3) growth of 0.5 cm or greater in 6 months based on serial cross-sectional imaging, again due to a risk of adrenocortical carcinoma; and (4) isolated metastasis from a remote primary malignancy.

Laparoscopic adrenalectomy is now considered standard practice due to its shorter duration of postoperative pain, shorter hospitalization, and faster return to work compared to an open procedure.

Contraindications to the transabdominal laparoscopic approach include severe cardiopulmonary disease and coagulopathy. Relative contraindications include prior intraabdominal surgery and very large tumor size.

The laparoscopic retroperitoneal approach is based on the historical open posterior approach. This approach is gaining popularity as it offers advantages over a laparoscopic transabdominal approach. These advantages include faster operating times, potentially less postoperative pain, a lower risk of complications (especially of incisional hernia), and improved intraoperative hemostasis as the surgeon has the ability to increase the insufflation pressure to 30 mmHg (a maneuver not feasible in a laparoscopic transabdominal approach given the negative impact on central venous return and renal perfusion).

The laparoscopic retroperitoneal approach does have some potential drawbacks. There is a slightly longer learning curve associated with the nontraditional “back-door” anatomic view. This approach may also be more difficult in patients with large tumors or who are morbidly obese.

The posterior approach is the ideal approach for bilateral procedures because it eliminates the need for patient repositioning. It is also preferable for patients who have had previous transabdominal operations.

Absolute contraindications to the laparoscopic retroperitoneal approach include the need to explore the rest of the abdomen and coagulopathy.

Relative contraindications include an adrenal mass greater than 8 cm due to the smaller working space, patient body mass index greater than 45 due to the patient’s pannus and visceral fat compressing the retroperitoneal working space. Severe cardiopulmonary disease is also a relative contraindication but may be less of an issue than for the transabdominal laparoscopic approach, as the diaphragm is not compressed to the same extent. Theoretically, increased ocular pressures are also a relative contraindication, as an extended time in a prone position would put the optic nerve at risk. This is usually only a problem for very long operations, however, and the vast majority of laparoscopic retroperitoneal adrenalectomies should not threaten the optic nerve.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

As with any endocrine disease, the workup of adrenal disease typically follows a logical progression, from making a biochemical diagnosis to localizing the lesion to determining the indications for an operation. In deciding if an operation is indicated, the two principal questions to be answered are (1) “Is the mass functional?” and (2) “What is the risk for cancer (either primary or metastatic disease)?” Most functional tumors and most malignant lesions should be considered for resection, taking into account the patient’s overall health, prognosis, and preferences.

Aldosteronoma. Ideally, the potassium level should be normalized preoperatively. Potassium supplements and/or aldosterone antagonists may be employed to achieve this goal. Maintain or optimize the antihypertensive regimen preoperatively.

Pheochromocytoma. Give the patient an α-blocker such as phenoxybenzamine. Start at 10 mg twice daily and increase the frequency and dose as tolerated until the patient becomes slightly symptomatic (including mild orthostasis and stuffy nose). A selective α-blocker is a good alternative in an older male patient due to less reflex tachycardia and potential prostatism benefits. In addition, some patients may be candidates for calcium channel therapy instead. As α-blockade proceeds, it is critical to replete the intravascular space with liberal fluid and some additional salt intake preoperatively. β-Blockade may be started a few days prior to the operation if the patient becomes tachycardic. Do not start β-blockade prior to adequate α-blockade or the resulting unopposed α-mediated vasoconstriction may cause stroke, myocardial infarction, and even death. Close communication with the anesthesia team is critical throughout the operation as manipulation of the tumor may cause wide swings in hemodynamics. Ensure that the anesthesia team is equipped with short-acting vasoactive agents to control or support intraoperative blood pressure as needed.

Cortisol-producing tumor. Give stress-dose steroids prior to induction. The patient will require a careful steroid taper postoperatively and endocrinology consultation is recommended. Although no level I data is available, perioperative antibiotics should be considered due to the relative immunosuppressed state in a patient with cortisol excess.

Adrenocortical carcinoma. Primary adrenal cancers may manifest any or all of the biochemical irregularities found in the aforementioned tumors and should be addressed as appropriate. It is important to assess the vasculature for evidence of venous invasion and tumor thrombus, ideally with a magnetic resonance venogram or formal venogram. The

laparoscopic retroperitoneal approach should not be used in cases of very large or locally invasive adrenal tumors.

ANATOMY

The retroperitoneal space is bounded by the peritoneum laterally, the paraspinous muscle medially, the rib cage posteriorly (i.e., away from table), the kidney/adrenal gland/peritoneum anteriorly (i.e., toward the table), and the diaphragm superiorly.

The superior pole of the kidney and the paraspinous muscle serve as the major landmarks.

TECHNIQUES

PATIENT POSITIONING

A modification of the “Walz position”

Intubate, obtain intravenous/arterial access as indicated, and place a urinary catheter while patient is still on stretcher. Administer stress-dose steroids and perioperative antibiotics if indicated.

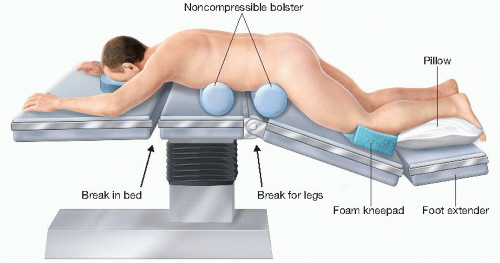

Place patient prone on two noncompressible bolsters with the lower bolster positioned at the break in the operating room (OR) table. The hips rest on the lower bolster. The lower ribcage rests on the upper bolster. The pannus should hang freely in between the bolsters to allow for the greatest amount of retroperitoneal working space. Place the operative side of the patient flush with that side of the table so that the table will not hinder the full range of motion of instruments, especially in the lateral-most port. If performing a bilateral adrenalectomy, the only patient repositioning necessary will be to shift the patient to the other edge of the bed (FIG 1).

FIG 1 • Patient positioning for a laparoscopic retroperitoneal adrenalectomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access