Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, Common Bile Duct Exploration, and Liver Biopsy

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy introduced operative laparoscopy to most general surgeons, and is often the first laparoscopic procedure performed by surgical residents. Although the anatomy is identical to that described in Chapter 63, the significance of some biliary anomalies is greater for the laparoscopic procedure. Accordingly, this chapter stresses not only surgical technique but also ways in which specific anatomic pitfalls can be avoided. It should be read in conjunction with Chapter 63.

Steps in Procedures—Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Obtain laparoscopic access and inspect abdomen

Place grasper on fundus of gallbladder and pull up and over the liver

Lyse any adhesions to omentum

Place second grasper on gallbladder infundibulum (Hartmann’s pouch)

Expose cystohepatic triangle

Incise peritoneum over distal gallbladder

Identify cystic duct and cystic artery

If cholangiogram is desired, insert catheter into cystic duct and secure it

Divide cystic duct and cystic artery

Dissect gallbladder from bed of liver, working in submucosal plane

Place gallbladder into retrieval bag and remove

Close trocar sites greater than 5 mm

Hallmark Anatomic Complications—Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Bile duct injury

Injury to duodenum

Injury to other surrounding viscera

Retained bile duct stone

List of Structures

Liver

Left lobe

Segments I, II, III, and IV

Right lobe

Segments V, VI, VII, and VIII

Falciform ligament

Ligamentum teres

Bile Duct

Common hepatic duct

Right and left hepatic ducts

Cystic duct

Left and right subphrenic spaces

Subhepatic space

Lesser sac

Duodenum

Greater omentum

Hepatic artery

Cystic artery

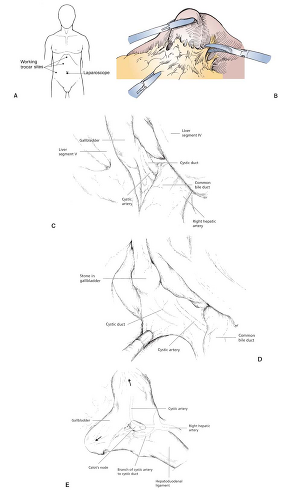

Initial Exposure (Fig. 64.1)

Technical Points

Introduce the laparoscope through an umbilical portal. Place a 10-mm port in the epigastric region and two 5-mm ports in the right midclavicular line and right anterior axillary line (Fig. 64.1A). Explore the abdomen. Cautiously lyse any adhesions of gallbladder to colon, omentum, or duodenum (Fig. 64.1B). Pass a grasping forceps through the anterior axillary line port and grasp the fundus of the gallbladder, pulling it up and over the liver. This will expose the subhepatic space (Fig. 64.1C). If the stomach and duodenum are distended, have suction placed on an orogastric or nasogastric tube. Reverse Trendelenburg positioning and tilting the operating table right side up will help increase the working space by allowing the viscera to move caudad and to the left.

Place a second grasping forceps through the midclavicular line port and grasp Hartmann’s pouch. Pull out, away from the liver. This maneuver will open Calot’s triangle and create a safe working space (Fig. 64.1D).

Take a moment to orient yourself. Frequently, there is an obvious color difference between the pale blue or green of the

gallbladder (unless severely diseased) and the yellow fat of Calot’s triangle. This blue-yellow junction is a good place to begin dissection. A few filmy adhesions of omentum, transverse colon, or duodenum may need to be cautiously lysed to provide optimum visualization of the region. Calot’s node, often enlarged in acute or resolving acute cholecystitis, nestles in Calot’s triangle (Fig. 64.1E).

gallbladder (unless severely diseased) and the yellow fat of Calot’s triangle. This blue-yellow junction is a good place to begin dissection. A few filmy adhesions of omentum, transverse colon, or duodenum may need to be cautiously lysed to provide optimum visualization of the region. Calot’s node, often enlarged in acute or resolving acute cholecystitis, nestles in Calot’s triangle (Fig. 64.1E).

|

Another good landmark is the hepatic artery, which should be visible as a large pulsating vessel well to the left of the surgical field. This is a marker for the bile duct, which generally lies just to the right.

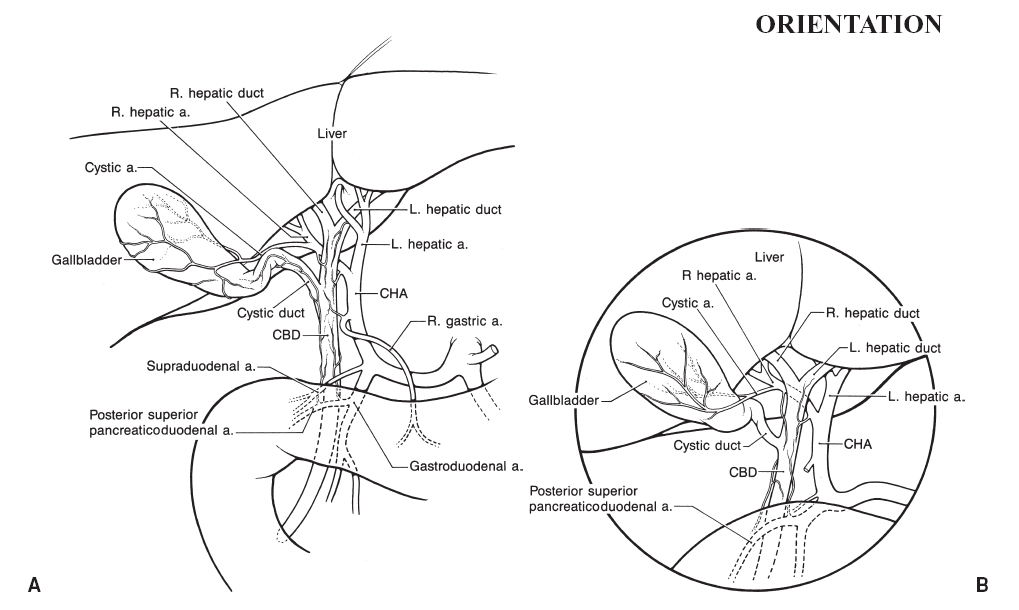

Anatomic Points

The cystic artery arises from the right hepatic artery in Calot’s triangle and ascends on the left side of the gallbladder in approximately 80% of individuals. A fatty stripe or slight tenting of the peritoneum overlying the gallbladder may serve as a clue to its probable location. In a significant minority of

individuals, the cystic artery arises directly from the hepatic artery. Other anomalies of the cystic artery of laparoscopic significance are described in Fig. 64.2.

individuals, the cystic artery arises directly from the hepatic artery. Other anomalies of the cystic artery of laparoscopic significance are described in Fig. 64.2.

Calot’s node is one of two fairly constant nodes in this region. The second node, termed the node of the anterior border of the epiploic foramen, lies along the upper part of the bile duct. Thus, simply noting the presence of a node in proximity to the bile duct does not guarantee a safe working distance from the bile duct.

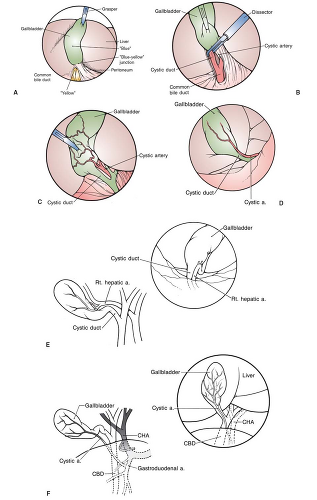

Initial Dissection (Fig. 64.2)

Technical Points

Incise the peritoneum overlying the blue-yellow junction (Fig. 64.2A). The cystic duct should become evident as a tubular structure which runs into the gallbladder. It is generally the closest structure to the laparoscope, and hence the first structure which is encountered. Develop a window behind the gallbladder by incising the gallbladder peritoneum on the left and right sides and blunt-dissecting behind cystic duct and gallbladder (Fig. 64.2B). The cystic artery should be visible to the left of the cystic duct (Fig. 64.2C).

Anatomic Points

The normal laparoscopic appearance is shown in Fig. 64.2D. As previously mentioned, this textbook pattern is present in approximately 80% of individuals. In 6% to 16% of normal individuals, the right hepatic artery passes close to the gallbladder (Fig. 64.2E). In such cases, the artery may assume a tortuous or “caterpillar hump”; this redundancy, combined with small arterial twigs to the gallbladder rather than a single cystic artery, renders the right hepatic artery susceptible to injury. The artery may be mistaken for the cystic artery and ligated, or may be damaged when these small twigs are controlled. Suspect this abnormality when the “cystic artery”

appears larger than normal. In up to 8% of normals, an accessory right hepatic artery may arise from the superior mesenteric artery or another vessel in the region pass in close proximity to Hartmann’s pouch as it ascends to the liver. More commonly, the cystic artery arises from the gastroduodenal artery or superior mesenteric artery and ascends to the gallbladder. This “low-lying” cystic artery will be encountered closer to the laparoscope than the cystic duct and may be mistaken for it.

appears larger than normal. In up to 8% of normals, an accessory right hepatic artery may arise from the superior mesenteric artery or another vessel in the region pass in close proximity to Hartmann’s pouch as it ascends to the liver. More commonly, the cystic artery arises from the gastroduodenal artery or superior mesenteric artery and ascends to the gallbladder. This “low-lying” cystic artery will be encountered closer to the laparoscope than the cystic duct and may be mistaken for it.

Figure 64-2 Initial Dissection (A–C from Scott-Conner CEH, Brunson CD. Surgery and anesthesia. In: Embury SH, Hebbel RP, eds. Sickle Cell Disease: Basic Principles and Clinical Practice. New York: Raven; 1994:809–827; D,E from Scott-Conner CEH, Hall TJ. Variant arterial anatomy in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1992;163:590, with permission; F from Cullen JJ, Scott-Conner CEH. Surgical anatomy of laparoscopic common duct exploration. In: Berci G, Cuschieri A, eds. Bile Ducts and Bile Duct Stones. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997:20–25, with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|