Kugel Technique of Groin Hernia Repair

Robert D. Kugel

John T. Moore

Hernia repair constitutes a major part of the typical general surgical practice. Expansive literature has been produced demonstrating benefits associated with a large number of repairs. Most of these repairs have focused on tension-free techniques. Tension-free repairs, when performed properly, reduce the risk of recurrence to low levels. These repairs also reduce postoperative pain and accelerate return to normal activity. Surgeons have been exposed to many mesh-designed tension-free repairs. In order to achieve the published results of these repairs, proper performance of the technique selected is the key element. These techniques require a thorough understanding of the procedures used as well as groin anatomy.

Indications

The Kugel technique for groin hernia repair is a tension-free, minimally invasive, yet open, preperitoneal or posterior abdominal wall groin hernia repair. It is applicable to the treatment of indirect and direct inguinal hernias as well as femoral hernias. It is particularly useful for the treatment of recurrent groin hernias after previously failed anterior repair. It can be used selectively in the patients having undergone prior radical prostatectomy or pelvic radiation, but should be avoided in the patients with recurrence after a failed laparoscopic groin hernia repair. This technique allows for rapid return to regular work and other activities without restriction. It further minimizes the risk of nerve injury and associated burdensome chronic pain syndromes because the inherent nature of this repair is to avoid direct nerve injury and avoid exposure of the groin nerves to the mesh.

Patient’s Selection

The key elements in successful hernia surgery are proper patient selection and proper performance of the repair. However, not all patients with hernias need to be repaired. Elderly, debilitated, and inactive patients with asymptomatic hernias where the hernia is easily reduced may be best left alone with rare exceptions. Symptomatic patients should all be repaired promptly. Even here, postponement of the repair may be considered if the symptoms are minimal and the hernia is easily reduced. Factors to consider are cost (immediate and delayed), age, patient health, and type of work. There is no question delaying a repair may create a much more different repair later with more complications. Incarceration also is a rare threat.

Not every patient with groin pain needs surgery. The groin area is particularly susceptible to injury. Muscle and ligamentous tears and strains can cause groin pain and even result in chronic pain, which will not improve with the hernia operation. Very small and occult hernias exist and can be particularly difficult to diagnose, especially femoral hernias. These can cause pain in patients, but in the absence of clear physical findings for a hernia, observation seems to be the best initial course. Special caution in patients is also warranted with a very short history of symptoms or a very long history of symptoms, who do not demonstrate positive physical findings of a hernia. Ultrasound in these patients is sometimes helpful, but frequently overstates the presence of a hernia. The ultrasound also does not correlate well with the symptomatology. A wait-and-see approach is advised in these patients if the surgeon is to avoid the not uncommon patient complaint after surgery that “the pain is worse now than before the surgery” or even “the mesh must be causing the pain.”

Though the bias of this presentation is that the Kugel technique is useful for the majority of groin hernias, there are incidences where it would be inappropriate (see indications) and even might not be the best technique. Although Kugel technique is great for bilateral hernias and for obese patients, it might be easier to treat the morbidly obese patient with a different technique.

The Mesh Patch

The Bard Kugel patch (Davol, Cranston, Rhode Island) was developed to facilitate performance of the Kugel hernia repair. Although it is started out as a simple single-layer mesh, it became progressively more intricate in order to make the performance of the procedure easier and the repair more secure.

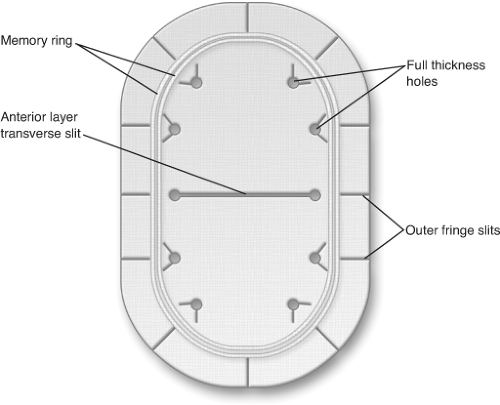

Fig. 1. Memory ring, anterior layer transverse slit, outer fringe slits, and full thickness holes are illustrated. |

The patch is composed of two overlapping layers of knitted monofilament polypropylene mesh material that are ultrasonically welded together (Fig. 1). A pocket of polypropylene is constructed on the outer

edge of the patch which contains a single polyester fiber spring or stiffener that helps the patch unfold after placement and maintain its configuration. One centimeter of mesh material extends beyond the outermost welds into which have been cut multiple radial slits. This outer fringe allows the patch to conform and fill more perfectly in the preperitoneal space, particularly when the patch folds back over the iliac vessels. A transverse slit is made in the center anterior patch, which is utilized for insertion of a finger which helps in positioning the patch in the preperitoneal space. Just beyond the anterior slit and inside of the mesh ring are multiple 3 mm holes through both layers of the patch. These serve to allow tissue-to-tissue contact through the patch to prevent movement of the patch after placement. This movement prevention is further augmented by several small V-shaped cuts associated with all of these holes in the anterior layer only. These cuts create a triangle of mesh which tends to pop-up when the patch is placed, and these act as sutureless anchors for the patch.

edge of the patch which contains a single polyester fiber spring or stiffener that helps the patch unfold after placement and maintain its configuration. One centimeter of mesh material extends beyond the outermost welds into which have been cut multiple radial slits. This outer fringe allows the patch to conform and fill more perfectly in the preperitoneal space, particularly when the patch folds back over the iliac vessels. A transverse slit is made in the center anterior patch, which is utilized for insertion of a finger which helps in positioning the patch in the preperitoneal space. Just beyond the anterior slit and inside of the mesh ring are multiple 3 mm holes through both layers of the patch. These serve to allow tissue-to-tissue contact through the patch to prevent movement of the patch after placement. This movement prevention is further augmented by several small V-shaped cuts associated with all of these holes in the anterior layer only. These cuts create a triangle of mesh which tends to pop-up when the patch is placed, and these act as sutureless anchors for the patch.

There are two mesh sizes used for groin hernias. The small patch is 8 × 12 cm and the medium patch is 11 × 14 cm. The small patch is adequate in most patients; however, the medium patch does provide greater margin for error and is preferred in very large hernias. It is up to the surgeon to decide the appropriate size of the mesh patch to be used, recognizing that the greater amount of underlay will probably result in fewer recurrences.

Operative Procedure

Anesthesia

General Anesthesia: This is the author’s anesthetic of choice for this operation. The primary disadvantage of a general anesthesia is the limitation of the ability to test the repair at the completion of the operation.

Regional Anesthesia: This is the preferred choice for some patients with epidural anesthesia being preferred over spinal anesthesia. The epidural anesthetic has the advantage for re-dosing when the catheter is left in place during the procedure. This not only allows for minimal initial dose, but also for the administration of additional doses as needed if the operation takes longer, which may happen with bilateral hernias. Furthermore, epidural anesthesia results in less muscle paralysis, enabling the patient to respond more forcefully when testing the repair following the operation.

Local Anesthesia: The author has preformed this procedure using local anesthesia and has monitored anesthesia care provided by an anesthesiologist, but maintenance of a relaxed patient is imperative to be able to enter and maintain appropriate visualization of the preperitoneal space through the incision. If the patient experiences pain and begins to bear down in response, it can make the procedure very difficult. Very obese patients with recurrent hernias or the patients who do not tolerate monitored anesthesia care should not be done under local anesthesia because of the loss of visualization associated with muscle contraction and discomfort.

Patient Preparation

Appropriate laboratory and radiographic evaluation of patients preoperatively depends on the surgeon and the policies and procedures of the facilities in which they practice. Because of the risk of bleeding into the preperitoneal space, it is recommended that Coumadin be stopped 3 to 5 days prior to the surgery. Use of prophylactic antibiotics is recommended due to the implantation of the foreign body into the wound. Although infection reduction is not clearly substantiated in controlled studies, antibiotics add little risk and may reduce graft infections.

Clipping of hair in the operative area is recommended over shaving at the time of the procedure, followed by an appropriate skin preparation.

The patient is positioned in a supine manner. During the operation, exposure is improved by placing the patient in a Trendelenburg position with slight rotation away from the site of the procedure.

Regardless of the type of the hernia to be repaired, the mesh patch is placed in the same fashion into the preperitoneal space in every patient. The repair can be more difficult to achieve because of the lack of familiarity with the anatomy in the posterior space and the angle in which the repair is approached. Understanding the unique approach is the key to the successful performance of this procedure. Ideal first patients are of average size or thin where the anatomy should be clearly visible. Avoid recurrent hernias or large scrotal hernias initially. One of the advantages of this repair is the ease with which it can be converted into an anterior repair. The surgeon needs to back out of the preperitoneal space, allow the internal oblique muscle to re-approximate, and extend the skin and external oblique incision through the external ring and perform an anterior repair.

Incision

The author thinks it is critical to utilize a headlight during the performance of this operation. Because of the angle in which the repair is approached, the headlight helps illuminate extremely well the area of the preperitoneal space and allows for accurate placement and deployment of the mesh patch. In addition, use of a dedicated assistant is also extremely helpful. The operation can be performed with the surgical scrub functioning as the assistant. A dedicated assistant, particularly in larger patients, allows for continued visualization of the preperitoneal space through continuous retraction.

Incision placement is important and can have a bearing on how easy it is to perform the operation (Fig. 2). The most important thing is to avoid making the incision too low. The ideal is to pass directly through the skin, muscle, and fascia into the preperitoneal space. This approach is superior to the internal ring and lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. It avoids the inguinal canal. Marking the anatomic landmarks on the surface of the patient will insure the correct placement of the incision. Identify the anterior superior iliac crest and the pubic tubercle. Measure the distance between these two points and mark the halfway point. This identifies the location of the internal ring. Measure directly superior to this point identified as the internal ring 2 cm and mark the site of the incision. This appropriately positions the incision in the high position to avoid entering into the inguinal canal. A 4-cm oblique incision is made with two-thirds of the incision being made medial to the point marked on the skin and one-third of the incision lateral. Four centimeters is an arbitrary measurement. In the initial performance of this operation, the surgeon may want to make a slightly larger incision as it does not affect the overall outcomes of this operation and may give better visualization.

The skin incisions can be made either transversely or obliquely, but oblique incisions enable the surgeon to move into a more conventional anterior repair, if needed, with less difficulty. The author prefers to make an oblique incision. The incision is made straight down through the skin and subcutaneous tissue on to the external oblique fascia. The external oblique fascia is then opened a short distance in the direction

of its fibers, but not through the external ring. This exposes the underlying internal oblique muscle. Frequently, the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves can be visualized on the surface of the internal oblique muscle when the external oblique fascia is split. Great care should be taken to avoid traumatizing a sensory nerve when splitting the internal oblique muscle, otherwise there is no need to directly visualize the ilioinguinal or the iliohypogastric nerves at this point. The internal oblique muscle is bluntly split in the direction of its fibers to expose the transversalis fascia. The muscle splitting of the internal oblique musculature when placed in the proper position frequently lies inferior to the iliohypogastric nerve and medial to the ilioinguinal nerve. Transversus abdominis muscles fibers that are occasionally encountered superficial to the transversalis fascia may need to be split as well. The transversalis fascia at this level is frequently a very thin and fragile structure. It can usually be penetrated by gentle blunt dissection. On occasion when it is more tenacious, a cutting of the fascia may be necessary. It is recommended that this is done in a vertical manner to avoid injury to the inferior epigastric vessels which lie in the medial aspect of the incision. Identification of the preperitoneal space is made by the characteristic appearance of the fat of the preperitoneal space and the identification of the inferior epigastric vessels in the medial aspect of the incision. A crucial aspect of the operation is to ensure that the surgeon dissects within the preperitoneal space. Identification of the inferior epigastric vessels, which lie in the medial portion of the incision within the preperitoneal fat keeping the dissection posterior to these vessels, will assure the surgeon will complete the operation in the correct compartment.

of its fibers, but not through the external ring. This exposes the underlying internal oblique muscle. Frequently, the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves can be visualized on the surface of the internal oblique muscle when the external oblique fascia is split. Great care should be taken to avoid traumatizing a sensory nerve when splitting the internal oblique muscle, otherwise there is no need to directly visualize the ilioinguinal or the iliohypogastric nerves at this point. The internal oblique muscle is bluntly split in the direction of its fibers to expose the transversalis fascia. The muscle splitting of the internal oblique musculature when placed in the proper position frequently lies inferior to the iliohypogastric nerve and medial to the ilioinguinal nerve. Transversus abdominis muscles fibers that are occasionally encountered superficial to the transversalis fascia may need to be split as well. The transversalis fascia at this level is frequently a very thin and fragile structure. It can usually be penetrated by gentle blunt dissection. On occasion when it is more tenacious, a cutting of the fascia may be necessary. It is recommended that this is done in a vertical manner to avoid injury to the inferior epigastric vessels which lie in the medial aspect of the incision. Identification of the preperitoneal space is made by the characteristic appearance of the fat of the preperitoneal space and the identification of the inferior epigastric vessels in the medial aspect of the incision. A crucial aspect of the operation is to ensure that the surgeon dissects within the preperitoneal space. Identification of the inferior epigastric vessels, which lie in the medial portion of the incision within the preperitoneal fat keeping the dissection posterior to these vessels, will assure the surgeon will complete the operation in the correct compartment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree