Joint Medical and Marketing Activities

Fundamentally, there are only two ways of coordinating the economic activities of millions. One is central direction involving the use of coercion—the technique of the army and of the modern totalitarian state. The other is voluntary cooperation of individuals—the technique of the marketplace.

–Milton Friedman

Some people say that cats are sneaky, evil, and cruel. True, and they have many other fine qualities as well.

–Missy Dizick

Agreat portion of this book deals with strategic issues, and medical as well as marketing strategies often benefit by input from the other group. However, this chapter differs because it discusses various areas where the development of the plans and strategies of a new drug is viewed as a joint activity. Many medical activities benefit from joint planning and coordination with marketing, and the opposite is also true. Just like the quote above on cats, each group is often full of surprises for the other.

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN MARKETING AND MEDICAL GROUPS

Informal Interactions between Marketing and Medical Groups

There is a wide spectrum of informal professional interactions that occur between marketing and medical people within a company or between internal staff and external people. These interactions include spontaneous meetings and discussions, ad hoc meetings, preplanned brainstorming sessions, information presentations, and advice-seeking meetings. Requests for an informal review of plans, promotions, protocols, or reports that are not part of a standard operating procedure are also considered informal interactions.

Formal Interactions between Marketing and Medical Groups

Common types of formal interactions are considered under the following four broad headings.

Reviews without sign-off. Requests are often made from marketing to medical for reviews of specific information. This type of request is also made from medical to marketing groups. Reviews may be requested of ideas, documents, plans, protocols, reports, advertisements, or other types of information. The output may be either verbal or written. These may be discussed at small and/or large joint meetings.

Reviews with sign-off. The activities previously described may require a written sign-off to ensure that the other group is in agreement. The traditions and formality of the company determine the degree to which this is necessary. The standard operating procedures should indicate whether special forms, a memorandum, or a note on the document constitutes a sign-off.

Requests for activities to be performed. This usually involves marketing requesting medical groups to conduct one or more clinical trials. Other marketing requests for medical activities include conducting scientific symposia, preparing articles for publication, and helping to staff scientific exhibits at a medical convention. Medical may request marketing to participate in specific medical meetings (e.g., to present a marketing perspective), to provide marketing advice or data at any of many meetings, or to provide advice on protocols. Medical personnel who are astute about marketing issues may initiate a request for market research to be conducted.

Committees. Representatives of both groups may be asked to serve on any of several types of committees within the company. These include:

Marketing (or medical) committees, to which one or more members of the other group are invited as members or as observers in a more informal capacity

Committees of a nonmedical and nonmarketing group (e.g., finance, business development, licensing) on which both medical and marketing representatives sit

Corporate committees (e.g., board of directors) on which both medical and marketing representatives sit

Achieving a Spirit of Partnership that Facilitates Productive Relationships

Positive relationships between marketing and medical groups are most likely to occur when there are positive relationships among the most senior managers. Their feelings about the other group are unintentionally communicated (as well as intentionally) and rapidly spread throughout their own group. A desire for a true partnership is an important prerequisite to a positive relationship between groups. It is extraordinarily difficult to have a productive relationship when one or both people do not want the relationship to succeed or do not care if a successful relationship is created.

Companies with organizations and management systems that facilitate these relationships have a better chance at creating productive relationships. No single organization or management style is best or is required for success, but the strong desire to achieve success of a shared goal is necessary. If everyone in a company is focused on getting an important drug to the market that will save many lives or is at least aware of these efforts, this will help staff overlook the many annoyances that arise as part of day-to-day development issues. It is management’s obligation to ensure that this important goal is widely disseminated and heard within the organization.

It is sometimes a moving experience to see two people communicate effectively even though each speaks a different language and may not even understand much of what the other is saying. In contrast, two people who share the same culture, language, and even training often cannot agree or communicate effectively, despite attempts to do so. Such failure is often the result of unconscious (or conscious) desires not to communicate and agree.

Joint Planning Activities between Medical and Marketing Groups

Joint planning activities should be (a) focused on the accomplishment of the shared goal, (b) nonrigid, (c) initially broad in concept, and (d) sensitive to the need for modifications based on regulatory change or changes in medical practice resulting from a new drug that is introduced.

The broad concepts in the following list involve medical and marketing groups and are intended as guides to help create meaningful plans with the least number of problems.

Identify the goal and ensure it is realistic (e.g., new indication, new label claim).

Identify the time frame and priority of marketing studies to be conducted by medical groups.

Review the contents of medical protocols that are written for marketing-oriented studies or that contain aspects of particular interest to marketing.

Review all market research protocols to ensure they are designed well to address the objective(s).

Choose appropriate indications to develop a new (or older) drug.

Review a new drug’s development plan.

Identify areas where both groups have major interests (e.g., pharmacoeconomic and quality-of-life studies).

Developing a Single, Clear Marketing Message

It is extremely important to create a single, clear marketing message for every drug. Multiple messages, particularly for a new drug, tend to be confusing to physicians and others. Moreover, the messages are not remembered and can be counterproductive in that physicians will not prescribe a drug whose use and benefits are vague, complex, or confusing. Although it is the responsibility of marketing personnel to develop this message, it is desirable for the medical group to play a major role in its creation and in its review. These are the “key communication messages” that usually become the hallmark of the branding.

To develop this central message, marketing people traditionally ask medical staff the following questions:

What about this drug is important to patients?

What features of this drug are most unique?

Why would a physician choose this drug over other therapies to treat his or her patients?

What role would this drug be expected to have in the treatment of disease X?

What types of patients would you treat with this drug, in terms of disease type, severity, and other characteristics?

If everything went as well as you hoped in the clinical trials, what important benefits would this drug offer?

If everything went as you thought it would in the clinical trials, what important benefits would this drug offer?

What advantages does this drug have over other treatments (both on the market and known to be in development) for the same disease?

Although the answers to each of these questions could be almost identical, subtle differences might be elicited that would help the marketer develop a single marketing message. This concept should initially be discussed within the medical group. If the group is not in favor of the proposed message, then the basis of their objections must be determined (e.g., accuracy, ethics, or other reasons). It might be possible for medical to suggest a revised message that would be acceptable to marketing. Alternatively, marketing should always field test their message among an external group of physicians. At this stage, it is quite possible that marketing would have a number of messages it would want to compare. Market research could evaluate a number of messages with physicians who would be expected to prescribe that drug to determine which are meaningful and relevant to the target audience.

Converting a Prescription Drug to Over-the-counter Status

A company that desires to take a prescription drug to over-the-counter status (or to pharmacy status in some countries) must involve both marketing and medical personnel for this activity to be successful. Although this is the reason why this topic is briefly mentioned in this chapter, it is more thoroughly explored in Chapter 97.

The following comments only deal with the initial step of developing a comprehensive strategy to achieve this goal after a decision is reached to adopt this approach. This strategy should consider the following:

Market (customer) need

Synopsis and interpretation of efficacy data in humans

Synopsis and interpretation of safety data in humans (both during the investigational period and during marketing)

Synopsis and interpretation of the overall benefit-to-risk analysis

Synopsis and interpretation of safety data in animals

Preparation of a scientific review of the public health rationale to take the drug over the counter

Presentation of the previously mentioned material to experts and opinion leaders in the field and a subsequent assessment of their comments and recommendations; this meeting should also learn whether they agree with the over-the-counter concept

Market research conducted to determine the reasons why patients who use the drug will be able to use it safely and wisely as an over-the-counter product and are not likely to either overdose or underdose their condition

Other marketing research questions to explore are mentioned in Chapter 97.

After the meeting with experts and the market research with patients, the strategy should be reviewed by the company and revised as necessary. A meeting with regulatory authorities is desirable if it can be arranged. Further meetings with other important groups, particularly those affected by the proposed change (e.g., pharmacists), may be important to conduct. It is likely that the strategy will evolve as the project progresses.

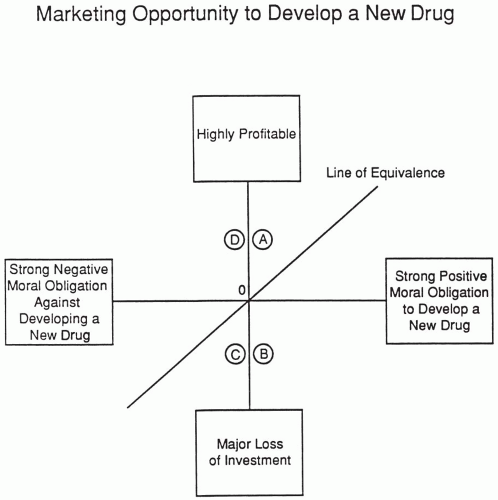

Moral Obligation to Develop a New Drug versus the Marketing Opportunity It Offers

One difficulty with using the particular scale of moral obligation is that the moral obligation for one person (or company) who is judging a compound could be the exact opposite of another person’s moral obligation. For example, an abortifacient that is safer and more effective than previous therapy could be viewed either as a major medical advance or as a major sin. A new drug that falls on the line of equivalence in Fig. 96.1 has relatively the same strength for both the extent of moral obligation to develop and the marketing opportunity. The further a drug is located from the line, the greater the potential for dissension and problems in a company. Some companies might choose not to develop a new drug of great profit if the moral obligation and public reactions are strongly negative. For example, it is well known that RU-486 (Mifepristone) was turned down for marketing by many companies that felt the public reactions to its use as a therapeutic abortion agent would be too great a risk for the company’s image and stock price to bear, making it difficult for a publicly traded company to develop this drug. Ultimately, the development was achieved by an independent organization.

Negative moral reasons against developing a drug could include that the drug has less safety or efficacy than existing therapy, the purpose of the drug is considered immoral (e.g., an abortifacient), or abuse of the drug might harm people [e.g., a date rape drug such as gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB)]. When Orphan Medical decided to develop GHB to treat cataplexy and daytime sleepiness associated with narcolepsy, it became necessary to differentiate between its legal and illegal uses, which was achieved by their working with the Food and

Drug Administration and a patient association to help pass a Congressional law making illegal uses a Drug Enforcement Administration Schedule I and legal uses a Drug Enforcement Administration Schedule III. If you are able to develop a drug that provides important medical value for patients and they agree with your assessments and with developing the drug, then there should be a company or organization willing to do the right thing and pursue development.

Drug Administration and a patient association to help pass a Congressional law making illegal uses a Drug Enforcement Administration Schedule I and legal uses a Drug Enforcement Administration Schedule III. If you are able to develop a drug that provides important medical value for patients and they agree with your assessments and with developing the drug, then there should be a company or organization willing to do the right thing and pursue development.

COLLABORATIVE APPROACHES TO VARIOUS ACTIVITIES

Preparing and Using Drug Labeling

How and when should a company prepare draft labeling for new drugs? At some stage, it is necessary to prepare a proposed package label for new investigational drugs. The copy submitted to the Food and Drug Administration in the United States must be fully annotated. This means that each statement in the draft label must reference a specific item, volume, and page in the New Drug Application or other appropriate place (e.g., Federal Register) that supports the statement.

The contents of the label may be driven by requirements for class labeling or by a particular style that the regulatory authority desires. A committee may be formed about a year prior to the anticipated submission to develop the label. One person may prepare an early draft, and after committee review, the draft could be circulated to the company’s experts within medical, marketing, legal, regulatory affairs, and other relevant groups for further comment and revision.

Using the Label to Forecast Drug Sales and Manufacturing Requirements

Marketing forecasts are based on the drug’s labeling. While tentative sales forecasts are made throughout a drug’s development, the most critical one (i.e., the one that influences the amount of drug manufactured) is the one completed between a few months and approximately a year before the final approval is expected. If the labeling submitted to a regulatory authority is unrealistic, then the marketing forecast based on that label will be unrealistic as well. This may cause a major problem if the company believes its own forecast, which may be a fantasy or a simple error, and manufactures an excessive quantity of drug. The company may create an excessively high inventory, even if the drug is approved at the predicted time.

Use of the Label for Establishing Promotional Boundaries

The critical importance of a drug’s labeling may also be demonstrated by the fact that the labeling establishes the bounds within

which a drug may be promoted; the major purpose of a New Drug Application document may be viewed as providing the evidence that supports the labeling. In the event that a critical aspect of proposed labeling is rejected by a regulatory authority, the company should have a fall-back position that can be more strongly defended.

which a drug may be promoted; the major purpose of a New Drug Application document may be viewed as providing the evidence that supports the labeling. In the event that a critical aspect of proposed labeling is rejected by a regulatory authority, the company should have a fall-back position that can be more strongly defended.

Modifying a Drug’s Label

When should a company modify its package insert of a marketed product? Some companies are much more reluctant than others to request that regulatory authorities allow modifications to their package inserts (e.g., to include additional adverse events). The initial suggestion to consider this possibility may come from various sources in a company, such as legal, medical, regulatory affairs, or marketing, and it often necessitates a meeting in which the company’s position on such a proposal can be constructed. The company’s decision about whether or not to request relabeling often depends on whose perspective is considered most influential [i.e., the representative from one of the previous areas may be the most important (or persuasive) in a specific company or on a specific topic].

Reimbursement of Drug Costs and Prices

The reimbursement of drugs is a huge topic including many issues that may be arbitrarily divided into four periods:

During drug development [Treatment Investigational New Drug Application (IND)]

During the drug approval process when reimbursement is being determined by a regulatory or other government agency

Postapproval, when the drug is (or is not) placed onto various formularies

At a later period when the level of reimbursement (in some countries) changes by government mandate

This brief section focuses on just the drug development and approval periods and involves both marketing input and pharmacoeconomic studies planned and carried out by company staff.

Reimbursement of drug costs refers to the investigational period, and reimbursement of drug prices refers to the other three periods mentioned earlier.

Components of Reimbursement

Reimbursement of patient costs for marketed products consists of three main parts: coverage, coding, and payment.

Coverage. This determines the drugs and services that are eligible for payment under the specific plan that the patient is enrolled in.

Coding. This refers to the nomenclature that is used to classify the specific disease (e.g., International Classification of Diseases-10) or problem encountered by the patient plus services received by the patient and any supplies that were used in treating the patient.

Payment. This defines the amount of money to be paid to the healthcare provider, hospital, or other facility, as well as any balance due from the patient and the procedures that must be followed for payment to be made.

In the United States, the payers include both government and private insurers, Health Maintenance Organizations, and other organizations, whereas in some European Union and other countries, it is the government that pays for most healthcare, including the drugs used in the provision of service.

Placing Products on Formularies

Formularies want to evaluate pharmacoeconomic data on a new product to evaluate its cost effectiveness. However, they also want comparative efficacy and safety data with one or more standard therapies used to treat the disease or problem. Ideally, this would involve effectiveness data in real-world settings as opposed to the artificial clinical trial setting, but (with few exceptions) those studies take time to conduct and usually only begin after the product is approved for marketing. Formularies also want to identify the portion of their population base that is likely to use a particular drug so that they can quantify their financial risk. They will examine the label, the indication, and possible off-label uses in addition to other issues to make these assessments.

The collection of pharmacoeconomic data in clinical trials is discussed in Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials (Spilker 1996) and briefly in Chapter 65.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

In the United States, the primary regulatory body for reimbursement is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). They established guidelines in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 that guide insurance companies and payers on formulary requirements. Most private and commercial insurers look to CMS and the Medicare reimbursement policy as the “gold standard” and use it as the basis for their respective policies. Pharmaceutical companies work closely with insurers and CMS to ensure that their products are included in the respective therapeutic classes.

Planning a Reimbursement Strategy during the Premarketing Period

It is essential to plan the postmarketing reimbursement strategy during Phases 2 and 3, and a reimbursement specialist should be part of the marketing team to ensure that the necessary data are collected to achieve reimbursement that the company seeks, including Medicare approval in the United States. The reimbursement strategy is often viewed as a road map to avoid costly duplicative studies and to ensure that data collected are able to achieve reimbursement. Some of the initial studies that are undertaken are done to understand the decision-making practices and procedures for US (government and nongovernment) bodies (e.g., Medicaid, Medicare) as well as those countries where the drug is expected to be marketed. In addition, the regulatory importance of reimbursement decisions is of enormous consequence in those countries where reimbursement is set by regulatory authorities or with their input.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree