Intravenous Anti-Secretory Therapy

Introduction

The concept of medication has been refined over thousands of years as physicians moved from rough herbal mixtures to crude chemicals and then to specific, albeit often impure, therapeutic agents. The subsequent development of more specific agents with defined targets led to the introduction of pharmacologic agents with distinct cellular and molecular destinations. In this respect, H2 receptor antagonists and PPIs represent the acme of such pharmacologic developmental strategies. An essential issue, however, remains the determination of the appropriate mode of delivery of such agents, since the route of administration is critical in determining not only the rate of onset of action, but also the duration of effect. In this respect, the issue of acid suppression in situations of critical illness such as encountered in intensive care units and postoperative patients in whom oral administration may not be possible has become a matter of considerable clinical relevance. In order to consider the potential clinical implications of the use of intravenous acid suppressants, it is worthwhile to consider the evolution of the concept of systemic pharmacotherapy as an adjunct to disease management. Clearly, the utility of an agent capable of bypassing the lengthy process of intestinal absorption and targeting the cell of interest (parietal) within seconds, if not minutes, is of considerable therapeutic interest and clinical relevance. Nevertheless, issues of stability, pharmacokinetics, and safety remain considerations that need careful evaluation.

Evolution of intravenous access

In early times, most medication was administered by local ointment application or orally or rectally. In the last instance, either the condition of the patient or the vile taste of the concoction precluded oral ingestion, and elaborate clysters were developed as well as elegant enema syringes. The effect of oral medication was fraught with unpredictable absorption or even emesis, while rectal administration sometimes encountered difficulties with retention as well as noxious local effects. As a result of this parlous state of affairs, physicians of the seventeenth century considered alternative methods of delivering therapy. There is little doubt that the discovery by William Harvey of the circulation of blood represented one of the most significant events in the history of medicine. The publication of the text De Motu Cordis in Frankfurt in 1628 laid the basis for the consideration of intravenous medication, although almost 30 years would pass before the first substantive studies were undertaken. Nevertheless, it was soon apparent that use of the venous system as a therapeutic conduit was clearly of great medical import, and by 1664, the procedures of infusion and transfusion were considered of such magnitude that a serious dispute arose between John Daniel Major, professor of physics at Kiel, and Elshotz, the King of Prussia’s physician at Berlin, as to their legitimate primacy in establishing this therapy.

Although the acrimonious dispute was widely aired in the medical periodicals for 3 years, their respective claims were to no avail, since the primary inventor was Christopher Wren, the mathematical professor at Oxford. Michael Ettmuller, a distinguished German physician practicing in Leipzig in 1668, stated categorically that primacy was the due of Wren and that following his contributions, the technique and concepts had been improved by Clarke, physician-in-ordinary to the King of England. Thereafter, Major had begun to use it, followed shortly by Charles Fracassatus, professor at Pisa, and last of all by Elshotz and Hoffmann, Professor at Altdorf.

Although the acrimonious dispute was widely aired in the medical periodicals for 3 years, their respective claims were to no avail, since the primary inventor was Christopher Wren, the mathematical professor at Oxford. Michael Ettmuller, a distinguished German physician practicing in Leipzig in 1668, stated categorically that primacy was the due of Wren and that following his contributions, the technique and concepts had been improved by Clarke, physician-in-ordinary to the King of England. Thereafter, Major had begun to use it, followed shortly by Charles Fracassatus, professor at Pisa, and last of all by Elshotz and Hoffmann, Professor at Altdorf.

Although it is not well known, Wren was none other than the eminent architect Sir Christopher Wren, who built St. Paul’s cathedral and the numerous other magnificent edifices that grace the cities of London and Oxford. Wren, in the words of the historian of the Royal Society, “became the first author of the noble and anatomical experiment of injecting liquors into the veins of animals; an experiment now vulgarly known but long since exhibited at meetings at Oxford and thence carried by some Germans and published abroad. By this operation diverse creatures were immediately purged, vomited, intoxicated, killed or revived according to the liquors injected. Hence arose many new experiments and chiefly those of transfusing blood, which the Society has prosecuted in sundry instances, that will probably end in extraordinary success.”

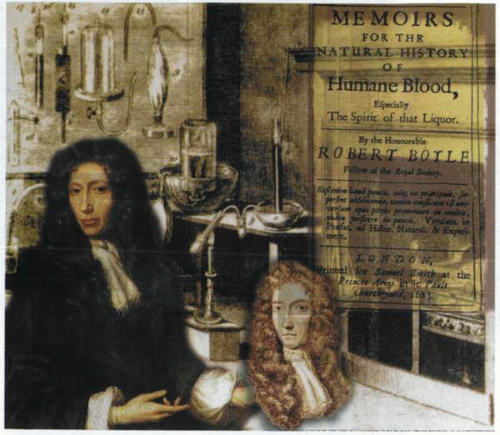

The events that led to the investigation of accessing the blood stream were detailed by Robert Boyle, who himself was a scholar of considerable repute. Since Wren had indicated to Boyle that he thought he could easily contrive a way of conveying any liquid immediately into the blood stream, Boyle, being interested, provided a large dog, and the demonstration was carried out in the presence of some eminent physicians and other learned men.

“Wren exposed the large vein in the hind leg and applied a small brass plate, half an inch long, a quarter of an inch broad, the sides being bent inwards. This plate had four little holes in the sides near the corners through which threads could be passed, allowing it to be fastened to the vein. In the middle of the plate there was a large slit parallel to the sides and almost as long as the plate. This allowed the vein to be exposed to the lancet and kept it from starting aside. The vein was ligatured below the plate and then opened through the slit sufficient to allow of the introduction of the slender pipe of a syringe. A small quantity of a warm solution of opium in sack was injected. The effect was dramatic. No sooner had the dog’s leg been untied than the opium began to show its narcotic qualities. Almost before the dog had scrambled to its feet its head began to nod, it faltered and reeled and became so stupid that wagers were offered that its life

could not be saved. Boyle, however, took the dog into the garden and caused it to be whipped up and down, thereby keeping it awake and in motion, whereby it gradually came round and, being carefully tended [for a change], it not only recovered fully but grew so fat so manifestly that ‘twas admired.’

could not be saved. Boyle, however, took the dog into the garden and caused it to be whipped up and down, thereby keeping it awake and in motion, whereby it gradually came round and, being carefully tended [for a change], it not only recovered fully but grew so fat so manifestly that ‘twas admired.’

Thus is recorded for posterity the initiation of intravenous access! Subsequent to these studies, Wren’s intellectual interest turned more toward astronomy and mathematics, and although he maintained a medical interest, he pursued physical science with considerable effect at Gresham College in London (1657) and subsequently as a professor at Oxford in 1661. While holding these posts, he not only continued to participate in medical discussions but actually illustrated Willis’s classic treatise on the anatomy of the brain, published in 1664. His subsequent ventures into architecture and the magnificent contributions of his genius to that area are a subject of a separate discussion. In these early experimental years, Boyle recorded that he was informed by an “ingenious anatomist and physician” that he had obtained very good success with diuretics. Boyle therefore proposed that if it could be done without too much danger or cruelty, trial might be made on some human bodies, especially those of malefactors. This was arranged in 1657, in the house of a foreign ambassador, “a curious person” residing in London at the time.

“Infusion of crocus metallorum was injected into the veins of an unruly domestic servant who, it was recorded, deserved to be hanged. The man, as soon as the injection was given, did either really or craftily fall in’to a swoon whereby, being unwilling to prosecute so hazardous an experiment, the ambassador desisted. The only other effect was that it wrought once downward with him which yet might be occasioned by fear or anguish.”

Timothy Clarke, physician-in-ordinary to King Charles the Second, recorded in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1668 that during the previous 10 years he had “diligently labored at mixing various fluids with blood drawn from living animals and had not only caused fluids of various kinds to be infused into the living body but had also demonstrated the effects of emetics, cathartics, diuretics, cardiacs and opiates in that way.” After examining the subject of “injections” (water, beer, milk, broth, wine, and spirits of wine) in both animals and humans for almost 5 years, he expressed doubt as to whether the technique would ever be of benefit in the cure of disease but thought it might have potential in the study of anatomy or for the better demonstration of the nature of blood. Unfortunately, Clarke failed to document the results of his experiments—possibly because of disappointment at the poor results—and stated that he did not consider the observations sufficiently worthy to enter into controversy regarding primacy. In consequence, others recorded Clarke’s experiments and subsequently claimed them as their own.

Among these, the first was John Sigismond Elshotz, who published an interesting little book entitled Clysmatica Nova, or the new clyster art, which described the method by which a medicine could be administered via an open blood vessel “so that it has the same effect as if it had been taken orally.”

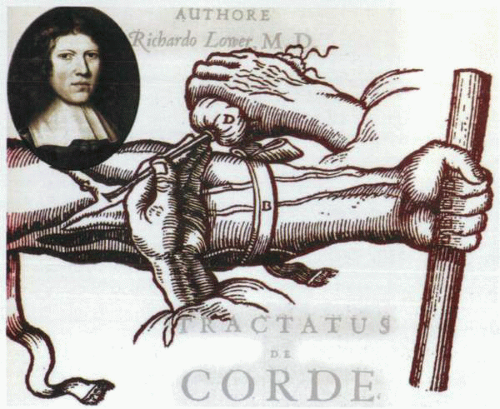

Richard Lower, a physician practicing in Oxford, was an early pioneer in developing the concepts and techniques of blood transfusion. Initially he used simple goose quills for uniting the blood vessels, but soon progressed to the use of silver-flanged (to facilitate a ligature) tubes connected by a piece of ox cervical artery that could be more securely fixed to the emitting and receiving blood vessels. At almost the same time in 1667, John Daniel Major, professor of physics at Kiel, published his book Chirurgia Infusoria, asserting angrily that the work confirmed his contributions as foremost in the new field and repudiated others who falsely claimed the credit! It is uncertain whether Major undertook any experimentation himself, and although the book resembles a compilation of the studies and opinions of others, it contains useful descriptions of the procedures as well as the earliest illustration known of an intravenous injection.

The next paper of importance was published in 1623 by a professor of anatomy at Pisa who injected into the vein of a dog some diluted aqua fortis. Unfortunately, the animal perished almost immediately, and on autopsy the blood in the vessels was found to be coagulated, and some of the greatest blood vessels had burst in a fashion reminiscent of those who had perished of apoplexy. An editorial in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society referring to experimental work on intravenous injection and blood transfusion taking place on the continent explained the cultural differences in experiments as follows: “why the curious in England make a demure in practicing this experiment upon men. The philosophers of England would have practiced it long ago if they had not been so tender in hazarding the life of men (which they take such pains to preserve and relieve) nor so scrupulous to incur the penalties of the law which in England is

more strict and nice in cases of this concernment than those of other nations are.”

more strict and nice in cases of this concernment than those of other nations are.”

Purmann, writing on the same subject almost a decade later in 1679, provided a more balanced analysis of the subject and a more thoughtful commentary: “That this Chirurgia Infusoria is beneficial in dangerous disease where the patient must be speedily helped, or all is lost, is very reasonable to believe; because the injected liquors speedily mix with the blood and are quickly conveyed to the heart and so through the whole body without suffering any alteration by the stomach or the several fermentative juices, but work immediately upon the diseases against which they are leveled.”

Purmann then documented some of the agents that he considered to be of particular benefit. These included Spirit salis ammoniaci, because it contained a volatile alkali without any oily material, Spirit of hartshorn and spirit of

human blood mixed with spirit of camphor, since these were capable of reviving the almost extinguished natural heat and bringing the patient to a sweat, particularly if mixed with two or three drachms of clear water.

human blood mixed with spirit of camphor, since these were capable of reviving the almost extinguished natural heat and bringing the patient to a sweat, particularly if mixed with two or three drachms of clear water.

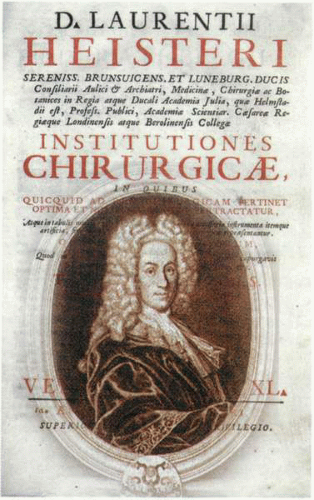

Heister in 1750 produced the best overall evaluation of the situation and commented that he believed that intravenous medication was in theory likely to be most useful in patients who could not swallow. Overall, the results were not only disappointing but even dangerous, with the therapy often worse than the disease. He noted “almost all the patients who have been this way treated have degenerated into a stupidity, foolishness or a raving or melancholy madness or else have been taken off with a sudden death either in or not long after the operation. These lamentable and fatal consequences have brought the art of injections and transfusions into neglect at present so that being suspected and condemned by proper judges at Paris, where they most flourished, we are told they were in a little time prohibited by public edict of that Government.”

Therapeutic infusion of fluid

James Blundell, lecturer in physiology and midwifery at Guy’s Hospital in 1818, had been interested for some years in the possibilities of successful blood transfusion in cases of postpartum hemorrhage. To this effect, he had undertaken numerous animal experiments and, having perfected the technique, wished to attempt a blood transfusion on a suitable human being. Fortuitously at this time, “a poor fellow named Brazier” between 30 and 40 years of age was admitted to Guy’s Hospital with what was subsequently proved to be “a scirrhosity of the pylorus.” Vomiting had reduced him to a helpless and hopeless appearance, and Blundell considered that transfusion alone might restore the quality of his life and enable his survival. The patient was agreeable! Three physicians, five surgeons, and several other gentlemen were present at the operation and supplied the blood. An ounce and a half was taken by syringe and immediately injected into the median vein, which had been opened by a lancet and into which a cannula had been placed and held in position by a finger. The operation began at two o’clock in the afternoon of 27 September 1818, and the procedure was repeated 10 times in the course of 30 to 40 minutes. Although no obvious change in the condition of the patient was evident during the transfusion, it was thought there were slight signs of improvement by the evening. Unfortunately, there was a dramatic deterioration in his condition the next day, and he died 56 hours after the start of the experiment. Blundell tried again without success on several occasions, but it was not until 7 December 1828 that he managed to produce a successful blood transfusion. The patient, a woman aged 25 years, was suffering from the results of a postpartum hemorrhage. Eight ounces of blood was injected during a period of 3 hours, and the patient expressed herself very strongly on the benefits of the transfusion, saying that she felt as if “life was being infused into her whole body.”

During studies performed in the early 1820s, François Magendie of Paris had found on frequent occasions that the injection of warm water into the veins of a mad dog would make it quiet. Thus, in October 1823, when asked to see a man in the Hotel Dieu suffering from hydrophobia who, despite copious

venesection, still had violent paroxysms and was clearly dying, Magendie elected to give an intravenous injection of water. The recovery of the patient was dramatic but, unfortunately, complications supervened, and he died 9 days later of septicemia, probably caused by the two lancets that had broken off and remained in his body after the process of blood-letting. Nevertheless, such was the reputation of Magendie in America that it prompted a dramatic medical experiment in intravenous medication in Boston. In 1824, a young physician named Hale allowed half an ounce of castor oil at a temperature of 70°F to be injected into the vein of his left arm by a friend who did not do the job very skillfully and engendered the loss of eight ounces of blood. Hale initially noted an oily taste in his mouth, which was followed by nausea and belching, trismus and dizziness, and then a major bowel evacuation. Although the experiment resulted in a month of illness, the arm in particular being swollen and inflamed, his strong constitution permitted recovery, and he was rewarded for his courage with a prize.

venesection, still had violent paroxysms and was clearly dying, Magendie elected to give an intravenous injection of water. The recovery of the patient was dramatic but, unfortunately, complications supervened, and he died 9 days later of septicemia, probably caused by the two lancets that had broken off and remained in his body after the process of blood-letting. Nevertheless, such was the reputation of Magendie in America that it prompted a dramatic medical experiment in intravenous medication in Boston. In 1824, a young physician named Hale allowed half an ounce of castor oil at a temperature of 70°F to be injected into the vein of his left arm by a friend who did not do the job very skillfully and engendered the loss of eight ounces of blood. Hale initially noted an oily taste in his mouth, which was followed by nausea and belching, trismus and dizziness, and then a major bowel evacuation. Although the experiment resulted in a month of illness, the arm in particular being swollen and inflamed, his strong constitution permitted recovery, and he was rewarded for his courage with a prize.

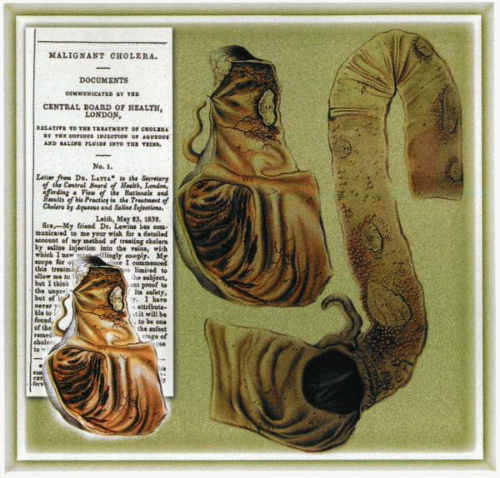

In 1832, during the cholera epidemic, an Edinburgh surgeon, Thomas Latta, had been impressed by an article on the postmortem findings in that disease. It was recorded “that there was a very great deficiency of the water and saline matter of the blood, on which deficiency the thick, black, cold state of the vital fluid depends, which evidently produces most of the distressing symptoms of that fearful complaint and is doubtless often the cause of death.” Latta attempted to replace the fluid loss by means of copious enemata of warm water with the requisite salts and by administering fluids by mouth. Finding these methods useless, and even harmful, he decided “to throw fluid immediately into the circulation.” His first patient was an old woman on whom all the usual remedies for cholera had been tried without effect with the result that she was almost moribund and even a dangerous experimental treatment could not be deemed to harm her further. Latta inserted a tube into the median basilic vein and slowly injected 6 pints of water containing 2 or 3 drachms muriate (or chloride of soda and 2 scruples of subcarbonate of soda at a temperature of 112°F). The injection took half an hour, at the end of which time she expressed in a firm voice that she was free from all uneasiness, actually became jocular, and fancied all she needed was a little sleep. Her extremities were warm, and every feature bore the aspect of comfort and health. Delighted with the outcome, Latta departed, but soon thereafter, the vomiting and diarrhea recurred and she died 6 hours later. As a result of this sad event, Latta realized that, despite any degree of improvement, the patient should never be left, and everything held in readiness

for a second or a third injection. As a result of this continuous therapy, a “very destitute woman of fifty” was given 16 and a half pints of fluid in 12 hours, and her life was saved. In yet another case, 19 pints were injected in 53 hours with a similar success, and Latta was able to present a convincing argument in favor of the early use of intravenous injections of saline in cases of cholera. Indeed, the principles of his therapy instituted in 1832 still remain in contemporary use.

for a second or a third injection. As a result of this continuous therapy, a “very destitute woman of fifty” was given 16 and a half pints of fluid in 12 hours, and her life was saved. In yet another case, 19 pints were injected in 53 hours with a similar success, and Latta was able to present a convincing argument in favor of the early use of intravenous injections of saline in cases of cholera. Indeed, the principles of his therapy instituted in 1832 still remain in contemporary use.

Blood as intravenous therapy

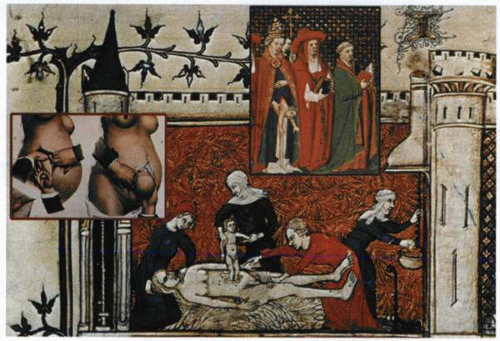

The use of blood in the treatment of disease dates back to the time of primitive man. The history of this phase of human thought is very extensive and complicated, involving such apparently diverse notions as vampirism and the bloody lintel of Passover. There is a certain amount of evidence to indicate that the practice of phlebotomy itself grew directly out of magical beliefs. Blood, as far as the primitive was concerned, was the seat of life and was used in magical practices. It is a common practice of some of the tribes of Africa and the Australian aboriginals to give human blood to the sick and aged for the purpose of strengthening them.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree