Insulinomas

Douglas L. Fraker

DEFINITION

Insulinomas are neoplasms arising from the beta cells of the pancreas. The vast majority are benign, sporadic, and unifocal.1,2 These neoplasms release insulin in a dysregulated manner and therefore cause decreased blood sugar, resulting in neuroglycopenic symptoms. Surgical excision uniformly provides long-term cure for the majority of benign insulinomas and corrects all of the associated symptoms.

ANATOMY

The beta cells of the pancreas are distributed amongst the pancreatic islets uniformly throughout the pancreas. For this reason, insulinomas can occur in all areas of the pancreas. Virtually all large series of insulinomas demonstrate that there is a uniform distribution related to the volume of pancreatic tissue.3, 4, 5 Half of insulinomas occur in the pancreatic head, neck, and uncinate process and the other half are distributed across the body and tail of the pancreas. Most series report insulinomas only occurring within the parenchyma of the pancreas. They can be exophytic and extend off the surface and these exophytic lesions may not be appreciated by standard cross-sectional imaging. There are reports of less than 2% of insulinomas being located outside of the pancreas parenchyma.1 Virtually all of these lesions are found in the wall of the duodenum and presumably, they occur within embryologic pancreatic rest tissue that is physically separate from the pancreatic parenchyma, such that the insulinoma occurs within the duodenal wall with a similar appearance to duodenal gastrinomas.

In most surgical series, insulinomas are small, measuring under 2 cm in cross-sectional diameter. Because symptomatology is caused by release of hormone and not by direct effects of tumor mass, lesions as small as 5 to 6 mm may present with significant clinical symptoms. In most series, 90% to 97% of insulinomas are benign. The average size of malignant insulinomas is over 6 cm and the majority of those present with concurrent regional lymph node or hepatic metastases.1,2

NATURAL HISTORY

Insulinomas cause virtually all of their symptoms due to excess circulation of insulin and the subsequent hypoglycemic effects. The first clinical case of insulinoma was described in 1927 when a patient who had severe hypoglycemic episodes had an abdominal operation with a large tumor of the pancreas and lymph node and liver metastases.2 Extracts of this tumor actually were injected into animals and caused hypoglycemia. Allen Whipple described the triad carrying his name that is known to define the symptoms of insulinoma in 1938. Whipple’s triad consists of hypoglycemia, documentation of hypoglycemia during periods of fasting, and relief of symptoms with administration of glucose. On analysis, this constellation of signs and symptoms is not truly a distinct triad but rather makes a single point of symptoms related to low blood sugar.6

The majority of symptoms experienced by patients relate to lack of blood glucose to the central nervous system. These are called neuroglycopenic symptoms and can range from mild confusion to coma. Patients may experience visual disturbances and there are numerous reports in the literature of insulinoma being misdiagnosed as an epileptic seizure. A second set of symptoms relate to the sympathetic nervous system release of adrenaline due to the effects of the hypoglycemia. This catecholamine release leads to palpitations, diaphoresis, and tremors. In most series, the onset of symptoms initially noted by the patient may be years before the specific time of diagnosis of the insulinoma. The average interval from onset of symptoms to diagnosis is between 2 to 3 years but sometimes may exist for over 10 years. Patients adapt and know that when they experience their symptoms, intake of food, particularly carbohydrates, provide rapid relief; however, this practice of glucose intake may not be elicited when taking a clinical history. Although the majority of patients exhibit weight gain in the anabolic state of hyperinsulinemia, some patients maintain a normal weight.

The vast majority of patients with insulinoma have sporadic tumors with no family history. A small proportion is associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1).5 The most common functional neuroendocrine tumor in MEN-1 is gastrinoma; outnumbering insulinoma by threeor fourfold. Insulinoma is the second most common pancreatic tumor in this syndrome. Because patients with MEN-1 may have multifocal nonfunctional neuroendocrine tumors throughout the pancreas, it may be difficult to distinguish the lesion making insulin versus other tumors. Typically, the dominant neuroendocrine tumor is the insulinoma but occasionally, patients will have multiple large lesions. Intraoperative measurement of insulin from direct tumor aspiration has been reported as an adjunct to insulinoma identification in this unusual situation.

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS

The key to diagnosis of insulinoma is not with imaging but rather with biochemical testing. The cornerstone of diagnosing hypoglycemia is detecting glucose levels typically below 40 mg/dL. Additional blood tests that should be obtained are insulin levels, proinsulin levels, and C-peptide levels.7 Virtually all patients will have a plasma insulin concentration greater than 5 µU/mL at the time of low blood glucose. The vast majority of patients have insulin levels greater than 10 µU/mL. The insulin to glucose ratio can define hypoglycemia due to insulinoma as opposed to other causes with high specificity and sensitivity.8 The measurements of proinsulin levels and C peptide are helpful in eliminating the diagnosis of surreptitious insulin abuse. The majority of patients have a proinsulin to insulin ratio greater than 25% and a C-peptide concentration greater than 1.7 ng/mL.

The gold standard for confirming the diagnosis of an insulinoma is a monitored 48-hour or 72-hour fast.9,10 Patients are typically in the inpatient setting given intravenous normal saline without glucose or allowed to drink noncaloric compounds while monitored for clinical symptoms and sequential blood analysis. The vast majority of patients who truly have an insulinoma causing hypoglycemia become symptomatic within the first 24 hours of the fast and virtually 100% of patients will become symptomatic by 72 hours. As time progresses, patients’ symptoms include decreased mental acuity, confusion, or other neuroglycopenic symptoms, which are documented by the nursing staff and physicians during the monitored fast. When symptoms reach a significant level, blood is drawn for glucose, insulin, and proinsulin before administering glucose to relieve the neurologic symptoms.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of hypoglycemia includes surreptitious use of either insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents and noninsulinoma pancreatogenous hypoglycemia syndrome (NIPHS).7,11 In general, blood tests for proinsulin, C peptide, as well as specific tests for sulfonylureas can eliminate the use of surreptitious agents. NIPHS is distinguished from insulinoma by the timing of hypoglycemia. These patients often do not become symptomatic during a 72-hour monitored fast but will become profoundly hypoglycemic after ingesting glucose orally.7 Pathology often shows significant beta cell hypertrophy but does not show a mass on imaging.

IMAGING

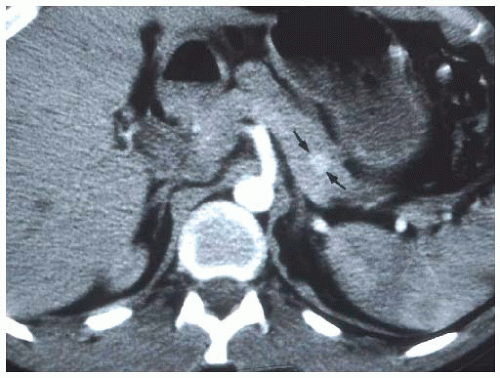

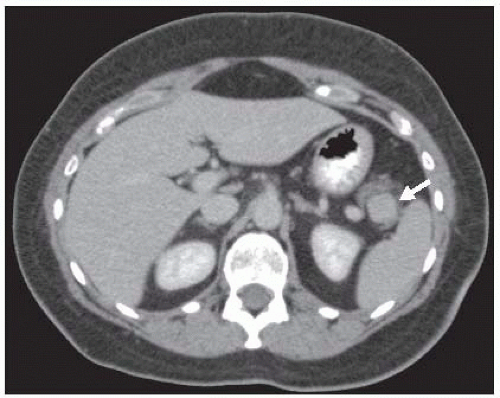

The vast majority of insulinomas are small and are located within the substance of the pancreatic parenchyma. The three choices of imaging that have been highly specific for identifying the insulinoma are contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, or endoscopic ultrasound.12,13 Insulinomas are hypervascular with very well-defined margins and have a classic appearance on enhanced CT and MRI scans (FIGS 1 and 2). They are oval-shaped, well-marginated, and show a characteristic vascular blush.12 The limitations of imaging relate to the size of the lesions. Again, insulinomas may cause symptoms that mandate surgical resection for correction with sizes smaller than 5 to 6 mm. Small insulinomas are ones that would be potentially missed on cross-sectional imaging studies. Also, exophytic lesions which may not be surrounded by pancreatic parenchyma may be a challenge to identify on CT or MRI, particularly if they are small. Insulinomas located near the tip of the pancreatic tail are the most common location for falsenegative imaging; insulinomas may be incorrectly identified as lymph nodes, accessory spleens, and splenic vessels.

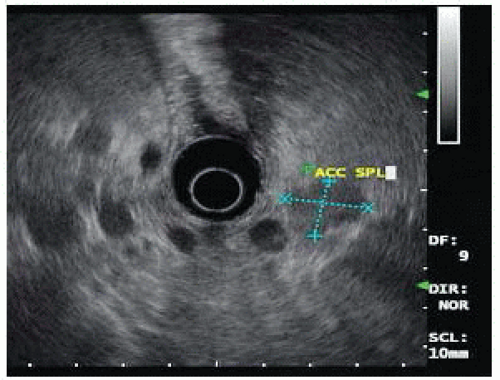

FIG 3 • Endoscopic ultrasound image of the same patient in FIG 2. The insulinoma is oval shaped and hypoechoic. The gastroenterologist has incorrectly labeled the insulinoma as accessory spleen.

Since the early 1990s, a variety of institutions with large experience in insulinoma have used endoscopic ultrasound as the primary imaging technique.12,13 Endoscopic ultrasound allows for direct imaging in three dimensions with very close field ultrasonography of the head, neck, and uncinate process. The pancreatic body is less well imaged as it can only be seen from the placement of the ultrasound probe within the stomach and depending on the patient’s body habitus, the tail may be a blind zone for endoscopic ultrasound. The ultrasound appearance of insulinoma is an oval hypoechoic mass with well-defined margins (FIG 3). Endoscopic ultrasound also allows a relatively straightforward fine needle

aspiration biopsy, which would produce neuroendocrine cells on cytology to confirm the diagnosis. Positive imaging may occur with identification of peripancreatic lymph nodes that are often embedded on the surface of the pancreas or accessory spleen, which can be found on the surface or actually within the parenchyma of the pancreas primarily in the tail region. Standard fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans have been shown to be of limited value in insulinomas as these may not be particularly hypermetabolic lesions.14 A recent report showed a specific targeting agent of indium-labeled glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor that was sensitive for insulinomas and also could allow the use of a handheld intraoperative probe to detect these lesions.15 This technique is being developed in Switzerland and has not been widely adapted elsewhere.

Despite the high sensitivity of cross-sectional imaging and endoscopic ultrasound, a portion of patients with well-documented biochemical insulinoma may have no lesions imaged.16,17 Historically, an interventional radiology invasive procedure called portal venous sampling was used in which a transhepatic portal vein cannulation was performed and blood was drawn from various regions and tributaries from the portal vein and assayed for insulin.18,19 Portal venous sampling has now been replaced by intraarterial calcium stimulation with hepatic vein sampling. In this technique, two catheters are placed: one in the right hepatic vein and a second standard arterial angiogram catheter advanced into arterial branches feeding the pancreas. Calcium is injected into branches of the splenic artery supplying the body or tail or branches of the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery off the gastroduodenal artery or the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery off the superior mesenteric artery. Blood is drawn from the right hepatic vein at 0 second, 30 seconds, and 60 seconds after calcium infusion and an increased gradient of greater than twofold in the hepatic vein insulin levels is significant.18 This procedure does not image insulinoma but rather identifies the region of production of insulin. It is a highly specific test and may be helpful in focusing efforts in the operating room to one area or the other. It may justify performance of a blind distal pancreatectomy for patients without imaged lesions that have gradient in the body and tail, but a blind pancreaticoduodenectomy is virtually never indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree