Inguinal Lymph Node Dissection (Inguinofemoral and Ilioinguinal) for Metastatic Melanoma

Amod A. Sarnaik

Vernon K. Sondak

DEFINITION

Inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (or superficial inguinal lymph node dissection) is defined as the en bloc removal of all lymphatic tissue contained within the femoral triangle, as well as the node-bearing tissue superior to the inguinal ligament but superficial to the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis, up to the level of the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS).

The procedure can be combined with a pelvic (also known as deep inguinal) node dissection, in which case it is designated as an ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy, that includes the separate removal of the obturator and external iliac lymph nodes at least up to the level of the iliac bifurcation.

The procedure has been used for the management of inguinal metastasis from penile and vulvar carcinoma as well as cutaneous malignancies such as squamous cell, basal cell, adnexal, and Merkel cell carcinoma, but it is most commonly used for metastatic melanoma, the focus of this chapter.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Patients who present with a palpable inguinal mass with a history of melanoma should be considered to have metastatic melanoma until proven otherwise.

Patients who present with a palpable inguinal mass without a known history of melanoma should be investigated for a primary malignancy with complete skin/mucosal surface physical examination including the vulva, penis and perianal skin/anal canal, and a digital rectal examination to evaluate for melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer (squamous cell, basal cell, Merkel cell, or adnexal carcinoma), vulvar, penile, and anal cancer.

For patients presenting with a palpable groin mass but without history or physical evidence of skin/mucosal surface cancers, the differential diagnoses include inguinal/femoral hernias, femoral aneurysm, reactive/infectious lymphadenopathy (catscratch fever or posttraumatic), lymphoma, or metastatic cancer of unknown primary origin (including melanoma).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Prompt diagnosis of inguinal metastasis by the least invasive means when possible is a good start to minimize the morbidity of subsequent inguinal node dissection.

Patients with clinically occult inguinal disease can be diagnosed with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy for microscopic nodal disease identified with sentinel lymph node biopsy appears to be associated with less morbidity compared to lymphadenectomy for macroscopic nodal disease.1

Patients with palpable groin masses not determined to be an aneurysm or hernia should be considered for a percutaneous fine needle or core needle biopsy to establish the diagnosis. If the mass is difficult to palpate or characterize, a diagnostic ultrasound with subsequent ultrasound-guided biopsy could be considered. Open biopsy should be reserved for when percutaneous biopsy is nondiagnostic, as the resulting scar and biopsy cavity from an open biopsy of a palpable mass render subsequent lymphadenectomy technically more difficult and can often result in wider skin flaps than what otherwise would be necessary.2

Although currently considered to be the standard of care, the role of completion inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy in patients with micrometastatic melanoma found on sentinel lymph node biopsy is under investigation. Nodal observation as a potential alternative to immediate completion lymphadenectomy in melanoma patients with a positive sentinel node is being evaluated in the ongoing Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial II. The trial randomizes patients with a positive sentinel lymph node to either immediate lymphadenectomy or observation with serial clinical examinations and ultrasonography. The patients randomized to observation may undergo a delayed completion lymphadenectomy if there is regional recurrence or may avoid the procedure and its associated morbidity if there is no evidence of regional disease during follow-up.

Ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy is typically warranted for patients with radiographic evidence of metastatic disease in the pelvis. Other indications for an ilioinguinal lymph node dissection have not been definitively established and therefore are controversial. The clinical benefit of ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy for clinically occult metastatic disease when the pelvic nodes appear to be radiographically normal has not been demonstrated in a randomized, prospective trial to date. However, there are indications that are generally considered but not yet established.

Relative indications for ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy include any palpable inguinofemoral disease or four or more micrometastatic lymph nodes found at the setting of prior sentinel lymph node biopsy.

A possible but not yet established indication is any positive inguinofemoral sentinel lymph node biopsy result where the lymphoscintigraphy indicated evidence of “hot” nodes in the pelvis that were not removed in the sentinel lymph node procedure.

Some surgeons advocate for the positive status of the socalled “Cloquet’s node” as an indication for ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy. However, there is a lack of uniform definition of Cloquet’s node, as well as known examples

of lymphoscintigraphy performed for sentinel node biopsy where there is direct drainage from low or mid-inguinal nodes to pelvic nodes, bypassing all high inguinal nodes that would include Cloquet’s node. Due to these factors, we do not rely on the status of Cloquet’s node in any way.2

Inguinofemoral or ilioinguinal lymph node dissections are performed under general anesthesia; therefore, the patient should be assessed for perioperative cardiac risk factors and referred for preoperative testing including cardiac stress test when clinically warranted.

Patients should be clinically assessed for any preoperative lymphedema and typically are referred for fitted gradient compression stocking measurements to be used in the postoperative period. Although proof of the value of compression therapy is lacking, it is thought that early institution of compression therapy might minimize the risk of lymphedema in the early postoperative period.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Prior to lymphadenectomy, patients who are diagnosed with palpable inguinal metastatic melanoma typically are recommended to undergo whole body imaging (positron emission tomography-computed tomography [PET/CT] plus brain magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or equivalent). Surgery is typically pursued in the absence of biopsy-proven distant disease, whereas systemic therapy is typically pursued if biopsy-proven distant disease is found.

Patients who are diagnosed with micrometastatic inguinal melanoma by sentinel lymph node biopsy are not routinely recommended to undergo imaging due to the relatively low frequency of findings that are truly positive.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative planning for a complete lymphadenectomy starts with careful consideration of the diagnostic procedures required to establish the diagnosis of metastatic disease. Percutaneous needle biopsy where feasible should be considered for palpable disease as discussed above. Orientation of the sentinel node incision should be planned to facilitate a potential inguinal lymph node dissection that will include resection of the sentinel node biopsy scar and cavity.

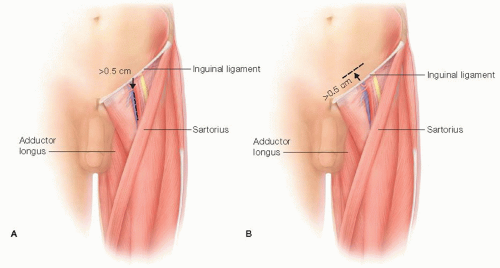

When the sentinel node is mapped below the inguinal ligament, the sentinel node incision should ideally be vertically oriented and at least 0.5 cm distal to the groin crease (FIG 1A).

When the sentinel node is mapped to above the inguinal ligament (typically with a flank primary melanoma), the sentinel node incision should ideally be obliquely or transversely oriented and at least 0.5 cm proximal to the groin crease (FIG 1B).

For planning the completion lymphadenectomy, the operative side and site should be identified with the agreement of the patient and/or the representative of the patient in the preoperative holding area.

Patients with a prior history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or known genetic predisposition to thrombosis are given a prophylactic dose of low-molecular-weight heparin preoperatively.

A first-generation cephalosporin such as cefazolin (or equivalent if allergic to cephalosporins or penicillin) are routinely given intravenously within 30-60 minutes of the creation of the skin incision.

Positioning

The patient is placed in the supine position on a standard operating table. A sequential compression device (SCD) (knee length ipsilateral and thigh length contralateral) should be placed for DVT prophylaxis prior to induction of anesthesia. General anesthesia is required using either a laryngeal mask or endotracheal tube for inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy, but endotracheal tube is preferred for ilioinguinal dissections. Long-acting paralytic agents at induction are often avoided to allow for motor nerve stimulation to be evident during the course of the procedure. A urinary catheter is inserted for ilioinguinal dissections but may potentially be omitted for inguinofemoral dissections at the discretion of the surgeon. The patient is placed in a slight frog-leg position with all pressure points padded. The operative field should be prepared from the abdominal wall at the level of the umbilicus to the level of the knee. A groin towel secured with a sterile adhesive drape can be used to cover and exclude the genitalia from the field.

TECHNIQUES

INGUINOFEMORAL (OR SUPERFICIAL) LYMPHADENECTOMY

Skin Incision and Raising of Flaps

As stated previously, a well-placed node biopsy incision, or avoiding the creation of a preexisting incision by percutaneous instead of open biopsy of palpable metastasis, is important to minimize the area of required skin flaps.

For a positive sentinel node where the sentinel node scar is below the inguinal crease, a curvilinear incision is made in a vertical orientation with an ellipse of skin to facilitate excision of the previous cavity of dissection (FIG 2A). For a positive sentinel node where the sentinel node scar is above the inguinal crease, a transversely or obliquely oriented incision is made to excise the previous cavity of dissection. A second counterincision can be made below the inguinal crease to reach the remaining femoral nodes (FIG 2B). In thin individuals, retraction can frequently allow for the extirpation of the femoral nodes distal to the inguinal crease without the need for the second incision.

For palpable disease without a pre-existing biopsy scar, a skin incision is configured in a lazy “S” fashion (FIG 2C). If the tumor is close to the skin, an ellipse of skin overlying the palpable tumor should be included. The incision should also include any scar from prior node biopsy procedure if applicable. This incision can be extended in a cranial direction if needed for an ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree