Information Technology and Clinical Research

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, concern grew among scientists, clinicians, and public policymakers regarding the direction of clinical research. Over the previous five decades, the scientific community had benefited from significant progress in the realm of basic science research, backed by the public’s long-term investment in it. The concern over clinical research stemmed from the idea that scientific discoveries of these past generations were not being appropriately translated. This was addressed with numerous targeted initiatives, including the Clinical Research Roundtable at the Institute of Medicine in June 2000. This initiative identified four major challenges to the progress of clinical research: (1) enhancing public participation in clinical research, (2) funding, (3) an adequately trained workforce, and (4) developing information systems (1). The last challenge mentioned, and the focus of this section, highlights the idea that the use of information technology (IT) and standards not only improves healthcare delivery, accuracy, and patient safety (2) but also advances clinical research.

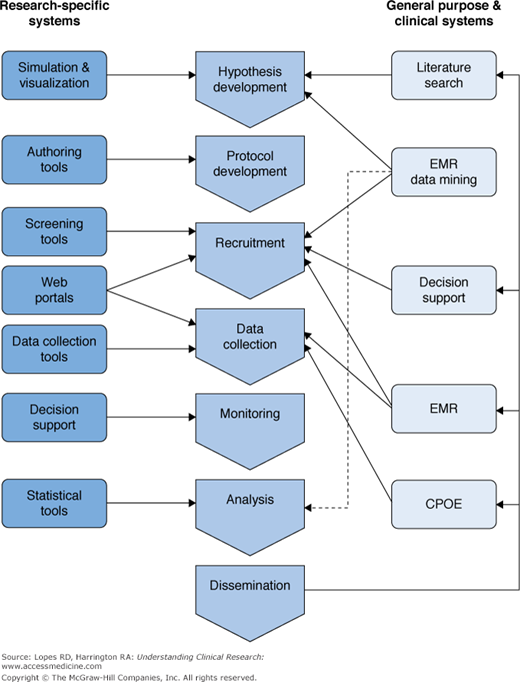

Information technology has now been integrated into every phase of clinical research. Physician–investigators use IT to assist in designing of hypotheses and protocols, identifying and recruiting research subjects, implementing data collection instruments, training research staff, ensuring regulatory compliance, and generating timely reports (1,3). IT applications have been tailored to both research and clinical systems; both have influenced the world of clinical research with considerable overlap (Figure 2–1) (4).

Figure 2–1.

Information technology systems supporting the translational research enterprise. CPOE, computerized physician order entry; EMR, electronic medical record. Reproduced, with permission, from Payne PRO, Johnson SB, Starren JB, Tilson HH, Dowdy D. Breaking the translational barriers: The value of integrating biomedical informatics and translational research. J Investig Med. 2005;53(4):192-200.

Clinical IT systems have made an enormous impact on clinical research and study design (5). Specifically, hypothesis development and study preparation have been enhanced by the ability to perform literature searches using tools such as PubMed (6). Cohort identification and study recruitment have been enhanced by data-mining tools, and decision support systems, including clinical trial alert systems, have helped identify study candidates (7,8). The electronic medical record has streamlined clinical data collection from research participants, reduced redundant data entry, and helped identify patients who qualify for clinical investigations; in addition, computerized physician order entry has allowed accurate tracking of therapies prescribed and delivered to study patients (9,10).

In addition to clinical IT systems, several research-specific IT systems have been developed that have led to increases in data and research quality. These are now being implemented in clinical research studies at growing rates (6,11). Table 2–1 outlines some of the research-specific IT systems and their utility in clinical research (12–16).

IT system | Application in clinical research |

|---|---|

Simulation and visualization tools | Streamline the preclinical research process (e.g., disease models) and assist in the analysis of complex datasets |

Protocol authorizing tools | Allow collaborating authors to work on complex protocols regardless of geographic location |

Research-specific Web portals | Allow researchers a single point of access for research information and collaboration |

Electronic data collection/capture tools | Organize research-specific data in a structured form, reduce redundancies and errors occurring with paper-based data collection |

IT systems and their application in clinical research have continued to evolve; Embi and colleagues proposed in 2009 that a new domain had emerged in medical informatics, referred to as clinical research informatics (17). They defined this new domain as:

… the subdomain of biomedical informatics concerned with the development, application, and evaluation of theories, methods, and systems to optimize the design and conduct of clinical research and the analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of the information generated.

Naturally, with the evolution of clinical research informatics and the development of large, integrated datasets, it became easier to pursue the idea of clinical trial registries, in which data from human trials could be available for mass consumption. Previously, the idea of clinical trial registries was met with many barriers and challenges, including the extensive resources needed to create and maintain the registries, the need to agree on standard data elements, the ability to manage data from multiple sources, the ability to regularly update and keep data accurate and complete, and proprietary/technical concerns (18). These challenges were addressed by the ever-changing idea of clinical research informatics, which led to next great debate in clinical research: To register or not to register?

Access to Clinical Research and ClinicalTrials.gov

The emergence of IT led to the rapid progression of clinical research and generation of massive amounts of data from human research subjects. While this was happening, concern developed in the medical and scientific communities that although clinical trials now had the potential to improve medical practice, significant access barriers persisted that created a gap between research and practice. This was eloquently suggested by Haynes and colleagues in 1998, who pointed to the volume and complexity of research being conducted and poor access to it as a significant barrier to practicing evidence-based medicine (19). The idea of registering clinical trials was picking up steam and supported by investigators such as Smith and colleagues, who in 1997 actually called for an “amnesty” for unpublished trials. Not surprisingly, they received a disappointing response (20).

Individual registries of small data did exist before 1998. A survey conducted by Easterbrook and colleagues in 1989 revealed 24 registries, including the internal registry of thrombosis and hemostasis trials and the Oxford Perinatal Trial Registry (21); there were also government-supported systems, including the AIDS Clinical Trials Information Service (ACTIS) and CancerNet (18). Over the next 10 years, more fragmented registries would develop, but they would continue to be limited by variance in recorded details and nonadherence to a standard of accuracy and comprehensiveness.

Several patient advocacy groups began to argue that clinical trials and their results should be made available to the public. This movement led to passage of the 1997 Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA), in which Section 113 required creation of a database of information about clinical trials. Specifically, it called for: