TABLE 8.1 Some Tests That Determine Antigen-Antibody Reactions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 8.2 Sensitivity of Commonly Used Serologic Tests for Syphilis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 8.3 Nonsyphilitic Conditions Giving Biologic False-Positive Results (BFPs) Using VDRL and RPR Tests | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PROCEDURAL ALERT

PROCEDURAL ALERT

Excess chyle released into the blood during digestion interferes with test results; therefore, the patient should fast for 8 hours.

Alcohol decreases reaction intensity in tests that detect reagin; therefore, alcohol ingestion should be avoided for at least 24 hours before blood is drawn.

Diagnosis of syphilis requires correlation of patient history, physical findings, and results of syphilis antibody tests. T. pallidum is diagnosed when both the screening and the confirmatory tests are reactive.

Treatment of syphilis may alter both the clinical course and the serologic pattern of the disease. Treatment related to tests that measure reagin (RPR and VDRL) includes the following measures:

If the patient is treated at the seronegative primary stage (e.g., after the appearance of the syphilitic chancre but before the appearance of reaction or reagin), the VDRL remains nonreactive.

If the patient is treated in the seropositive primary stage (e.g., after the appearance of a reaction), the VDRL usually becomes nonreactive within 6 months of treatment.

If the patient is treated during the secondary stage, the VDRL usually becomes nonreactive within 12 to 18 months.

If the patient is treated >10 years after the disease onset, the VDRL usually remains unchanged.

A negative serologic test may indicate one of the following circumstances:

The patient does not have syphilis.

The infection is too recent for antibodies to be produced. Repeat tests should be performed at 1-week, 1-month, and 3-month intervals to establish the presence or absence of disease.

The syphilis is in a latent or inactive phase.

The patient has a faulty immunodefense mechanism.

Laboratory techniques were faulty.

Hemolysis can cause false-positive results.

Hepatitis can result in a false-positive test.

Testing too soon after exposure can result in a false-negative test.

Explain test purpose and procedure. Assess for interfering factors. Instruct the patient to abstain from alcohol for at least 24 hours before the blood sample is drawn.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test results and counsel appropriately. Explain biologic false-positive or false-negative reactions. Advise that repeat testing may be necessary.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Sexual partners of patients with syphilis should be evaluated for the disease.

After treatment, patients with early-stage syphilis should be tested at 3-month intervals for 1 year to monitor for declining reactivity.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. CSF may also be used for the test.

Observe standard precautions.

Place specimen in a biohazard bag.

Ten proteins are useful in the serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. Positive blots are:

IgM: two of three of the following bands: 21/25, 39, and 41

IgG: five of the following bands: 18, 21/25, 28, 30, 39, 41, 45, 58, 66, and 93

Serologic tests lack the degree of sensitivity, specificity, and standardization necessary for diagnosis in the absence of clinical history. The antigen detection assay for bacterial proteins is of limited value in early stages of disease.

In patients presenting with a clinical picture of Lyme disease, negative serologic tests are inconclusive during the first month of infection.

Repeat paired testing should be performed if borderline values are reported.

The CDC states that the best clinical marker for Lyme disease is the initial skin lesion erythema migrans (EM), which occurs in 60% to 80% of patients.

CDC laboratory criteria for the diagnosis of Lyme disease include the following factors:

Isolation of B. burgdorferi from a clinical specimen

IgM and IgG antibodies in blood or CSF

Paired acute and convalescent blood samples showing significant antibody response to B. burgdorferi

False-positive results may occur with high levels of rheumatoid factors or in the presence of other spirochete infections, such as syphilis (cross-reactivity).

Asymptomatic individuals who spend time in endemic areas may have already produced antibodies to B. burgdorferi.

Assess patient’s clinical history, exposure risk, and knowledge regarding the test. Explain test purpose and procedure as well as possible follow-up testing.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcomes for a positive test. Advise the patient that follow-up testing may be required to monitor response to antibiotic therapy.

Unlike other diseases, people do not develop resistance to Lyme disease after infection and may continue to be at high risk, especially if they live, work, or recreate in areas where Lyme disease is present.

If Lyme disease has been ruled out, further testing may include Babesia microti, a parasite transmitted to humans by a tick bite. Symptoms include loss of appetite, fever, sweats, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, and headaches.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions. Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Follow-up testing is usually requested 3 to 6 weeks after initial symptom appearance.

Alert patient that a urine specimen may be required if antigen testing is indicated.

A dramatic rise of titer levels to more than 1:128 in the interval between acute- and convalescent-phase specimens occurs with recent infections.

Serologic tests, to be useful, must be performed on an acute (within 1 week of onset) and convalescent (3 to 6 weeks later) specimen.

Serologic testing is valuable because it provides a confirmatory diagnosis of L. pneumophila infection when other tests have failed. IFA is the serologic test of choice because it can detect all classes of antibodies.

Demonstration of L. pneumophila antigen in urine by ELISA is indicative of infection.

Assess clinical history and knowledge about the test. Explain purpose and procedure of blood test.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcomes and significance. Advise that negative results do not rule out L. pneumophila. Follow-up testing is usually needed.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions.

Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Presence of antibody titer indicates past chlamydial infection. A fourfold or greater rise in antibody titer between acute and convalescent specimens indicates recent infection. Serologic tests cannot differentiate among the species of Chlamydia.

Infection with psittacosis is revealed in an elevated antibody titer. History will reveal contact with infected birds (pets or poultry).

LGV in males is characterized by swollen and tender inguinal lymph nodes. In females, swelling occurs in the intra-abdominal, perirectal, and pelvic lymph nodes. Chlamydia causes urethritis in males. It can infect the female urethra and endocervix, and it is also a cause of pelvic inflammatory disease in females. Eye disease caused by Chlamydia is endemic in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, although its presence is established worldwide. Culture and stained smear identification of the organism is diagnostic.

Assess patient knowledge regarding the test and explain purpose and procedure. Elicit history regarding possible exposure to organism.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcomes and significance of test results; see Interpreting Results of Immunologic Tests.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions. Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Repeat testing 10 days after the first test is recommended.

In general, a titer >160 Todd units/mL is considered a definite elevation for the ASO test.

The ASO or the ADB test alone is positive in 80% to 85% of group A streptococcal infections (e.g., streptococcal pharyngitis, rheumatic fever, pyoderma, glomerulonephritis).

When ASO and ADB tests are run concurrently, 95% of streptococcal infections can be detected.

A repeatedly low titer is good evidence for the absence of active rheumatic fever. Conversely, a high titer does not necessarily mean rheumatic fever of glomerulonephritis is present; however, it does indicate the presence of a streptococcal infection.

ASO production is especially high in rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis. These conditions show marked ASO titer increases during the symptomless period preceding an attack. Also, ADB titers are particularly high in pyoderma.

An increased titer can occur in healthy carriers.

Antibiotic therapy suppresses streptococcal antibody response.

Increased B-lipoprotein levels inhibit streptolysin O and produce falsely high ASO titers.

Assess patient’s clinical history and test knowledge. Explain test purpose and procedure.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcomes; see Interpreting Results of Immunologic Tests. Inform patient that repeat testing is frequently required.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Breath: measures isotopically labeled CO2 in breath specimens

Stool: H. pylori stool antigen test (HpSa)

1. Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions. Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Be aware that a random stool specimen may be ordered to test for the presence of H. pylori antigen.

Remember that the breath test is a complex procedure and requires a special kit. Ensure that the collection balloon is fully inflated. Transfer the breath specimen to the laboratory. Keep at room temperature.

The13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT) requires the patient to swallow an isotopically labeled (13C) urea tablet. The urea is subsequently hydrolyzed to ammonia and labeled CO2 by the presence of H. pylori urease activity. After approximately 30 minutes, an exhaled breath sample is collected, and13CO2 levels are assessed using isotope ratio mass spectrometry.

PROCEDURAL ALERT

PROCEDURAL ALERT

The patient should have no antibiotics and bismuth for 1 month and no proton pump inhibitors and sucralfate for 2 weeks before test.

Instruct the patient not to chew the capsule.

The patient should be at rest during breath collection.

This assay is intended for use as an aid in the diagnosis of H. pylori, and additionally, false-negative results may occur. The clinical diagnosis should not be based on serology alone but rather on a combination of serology (and breath or stool tests), symptoms, and gastric biopsy-based tests as warranted.

The stool antigen test is used to monitor response during therapy and to test for cure after treatment.

Explain test purpose, procedure, and knowledge of signs and symptoms and risk factors for transmission: close living quarters, many persons in household, poor household sanitation and hygiene. The patient swallows a capsule before a breath specimen is obtained. The serum antibody test would be appropriate for a previously untreated patient with a documented history of gastroduodenal ulcer disease and unknown H. pylori infection status.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcomes in light of patient’s history, including other clinical and laboratory findings. Explain treatment (4 to 6 weeks of antibiotics to eradicate H. pylori and medication to suppress acid production) and need for follow-up testing. Transmission is unknown, but the potential for transmission may occur during episodes of gastrointestinal illness, particularly with vomiting. Many persons may be infected with H. pylori but are asymptomatic.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions.

Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

The presence of heterophile antibodies (Monospot), along with clinical signs and other hematologic findings, is diagnostic for IM.

Heterophile antibodies remain elevated for 8 to 12 weeks after symptoms appear.

Approximately 90% of adults have antibodies to the virus.

The Monospot test is negative more frequently in children and almost uniformly in infants with primary EBV infection.

Assess patient’s clinical history, symptoms, and test knowledge. Explain test purpose and procedure. If preliminary tests are negative, follow-up tests may be necessary.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcomes; see Interpreting Results of Immunologic Tests. Explain treatment (e.g., supportive therapy [intravenous fluids]). After primary exposure, a person is considered immune. Recurrence of IM is rare.

Remember that resolution of IM usually follows a predictable course: pharyngitis disappears within 14 days after onset; fever subsides within 21 days; and fatigue, lymphadenopathy, and liver and spleen enlargement regress by 21 to 28 days.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

alanine aminotransferase (ALT) that fluctuate between normal and markedly elevated. Levels of anti-HCV remain positive for many years; therefore, a reactive test indicates infection with HCV or a carrier state but not infectivity or immunity. PCR or reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) (viral load), which detects HCV RNA, should be used to confirm infection when acute hepatitis C is suspected. A negative hepatitis C antibody (recombinant immunoblot assay [RIBA]) does not exclude the possibility of HCV infection because seroconversion may not occur for up to 6 months after exposure.

TABLE 8.4 Hepatitis Test Findings in Various Stages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 8.5 Summary of Clinical and Epidemiologic Features of Viral Hepatitis Agents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Children should be vaccinated between 12 and 23 months of age.

Communities with existing vaccination programs for children 2 to 18 years of age should maintain their programs.

In areas without vaccination programs, catch-up vaccination of unvaccinated children 2 to 18 years of age can be considered.

Persons traveling to or working in countries that have high or intermediate endemicity

Users of injection and noninjection illicit drugs

Persons with clotting-factor disorders who have received solvent-detergent, treated high-purity factor VIII concentrates

Homosexual men

Individuals working with nonhuman HAV-infected primates

Food handlers

Persons employed in child care centers

Health care workers

Susceptible individuals with chronic liver disease

Family members of adoptees from foreign countries who are HBsAg positive

Health care workers (dentist, DO, MD, RN, and trainees in health care fields)

Hemodialysis patients or patients with early renal failure

Household or sexual contacts of persons chronically infected with hepatitis B

Immigrants from Africa or Southeast Asia; recommended for children <11 years old and all susceptible household contacts of persons chronically infected with hepatitis B

Injection drug users

Inmates of long-term correctional facilities

Clients and staff of institutions for the developmentally disabled

International travelers to countries of high or intermediate HBV endemicity

Laboratory workers

Public safety workers (e.g., police, fire fighters)

Recipients of clotting factors. Use a fine needle (<23 gauge) and firm pressure at injection site for >2 minutes.

Persons with STIs or multiple sexual partners in previous 6 months, prostitutes, homosexual and bisexual men

Postvaccination blood testing is recommended for sexual contacts of HBsAg-positive persons; health care workers, recipients of clotting factors, those who are HBsAg-positive are at high risk.

Persons in nonresidential day care programs should be vaccinated if an HBsAg-positive classmate behaves aggressively or has special medical problems that increase the risk for exposure to blood. Staff in nonresidential day care programs should be vaccinated if a client is HBsAg-positive.

Observe enteric and standard precautions for 7 days after onset of symptoms or jaundice with hepatitis B. Hepatitis A is most contagious before symptoms or jaundice appears.

Use standard blood and body fluid precautions for type B hepatitis and B antigen carriers. Precautions apply until the patient is HBsAg negative and the anti-HBs appears. Avoid “sharps” (e.g., needles, scalpel blades) injuries. Should accidental injury occur, encourage some bleeding, and wash area well with a germicidal soap. Report injury to proper department, and follow up with necessary interventions. Put on gown when blood splattering is anticipated. A private hospital room and bathroom may be indicated.

Persons with a history of receiving blood transfusion should not donate blood for 6 months. Transfusion-acquired hepatitis may not show up for 6 months after transfusion. Persons who test positive for HBsAg should never donate blood or plasma.

Persons who have sexual contact with hepatitis B-infected individuals run a greater risk for acquiring that same infection. HBsAg appears in most body fluids, including saliva, semen, and cervical secretions.

Observe standard precautions in all cases of suspected hepatitis until the diagnosis and hepatitis type are confirmed.

Negative (nonreactive) for hepatitis A, B, C, D, or E by ELISA, MEIA, PCR, RIBA, or RT-PCR

Negative or undetected viral load (not used for primary infection, only to monitor). PCR requires a separate specimen collection.

Hepatitis B viral DNA (HBV-DNA) negative or nonreactive viral load (<0.01 pg/mL) in an infected individual before treatment

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube or two lavender-topped ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes, 5 mL each, for plasma. Observe standard precautions. Centrifuge promptly and aseptically. Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory. Send specimens frozen on dry ice. Check with your laboratory for protocols and whether plasma or serum is needed.

Some specimens need to be split into two plastic vials before freezing and sent frozen on dry ice. Check with your laboratory.

Individuals with hepatitis may have generalized symptoms resembling the flu and may dismiss their illness as such.

A specific type of hepatitis cannot be differentiated by clinical observations alone. Testing is the only sure method to define the category (see Tables 8.6 and 8.7).

Rapid diagnosis of acute hepatitis is essential for the patient so that treatment can be instituted and for those who have close patient contact so that protective measures can be taken to prevent disease spread.

Persons at higher risk for acquiring hepatitis A include patients and staff in health care and custodial institutions, people in day care centers, intravenous drug abusers, and those who travel to undeveloped countries or regions where food and water supplies may be contaminated.

Persons at higher risk for hepatitis B include those with a history of drug abuse, those who have sexual contact with infected persons, those who have household contact with infected persons, and especially those with skin and mucosal surface lesions (e.g., impetigo, saliva from chronic HBV-infected persons on toothbrush racks and coffee cups in their homes); additionally, infants born to infected mothers (during delivery), hemodialysis patients, and health care employees are at higher risk for infection. Of all persons with HBV infection, 38% to 40% contract HBV during early childhood.

Health care workers should be periodically tested for hepatitis exposure and should always observe standard precautions when caring for patients.

Persons at risk for hepatitis C include those who have received blood transfusions, engage in intravenous drug abuse, undergo hemodialysis, have had organ transplantation, or have sexual contact with an infected person; hepatitis C can also be transmitted during delivery from mother to neonate. Most people are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis for hepatitis C. See Table 8.8 for hepatitis markers that appear after infection.

Both total (IgG + IgM) and IgM anti-HBc are positive in acute infection, whereas typically only total anti-HBc is present in chronic infection.

Assess patient’s social and clinical history and knowledge of test. Explain test purpose and procedure.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Explain significance of test results and counsel appropriately regarding presence of infection, recovery, and immunity.

Counsel health care workers and family regarding protective and preventive measures necessary to avoid transmission.

Instruct patients to alert health care workers and others regarding their hepatitis history in situations in which exposure to body fluids and wastes may occur.

Pregnant women may need special counseling.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

TABLE 8.6 Differential Diagnosis of Viral Hepatitis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 8.7 Viruses for Which Clinical Signs and Symptoms Mimic Hepatitis | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 8.8 Markers That Appear After Infection | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Observe enteric and standard precautions for 7 days after onset of symptoms or jaundice in hepatitis A. Hepatitis A is most contagious before symptoms or jaundice appears.

Use standard blood and body fluid precautions with hepatitis B and hepatitis B antigen carriers. Precautions apply until the patient is HBsAg negative and anti-HBs appears. Avoid “sharps” (e.g., needles, scalpel blades) injuries. Should accidental injury occur, encourage some bleeding, and wash area well with a germicidal soap. Report injury to proper department and follow up with necessary interventions. Put on gown when blood splattering is anticipated. A private hospital room and bathroom may be indicated.

If patient has had a blood transfusion, he or she should not donate blood for 6 months. Transfusion-acquired hepatitis may not show up for 6 months after transfusion. Persons who test positive for HBsAg should never donate blood or plasma.

Persons who have sexual contact with hepatitis B-infected individuals run a greater risk for acquiring the infection. HBsAg appears in most body fluids, including saliva, semen, and cervical secretions.

Standard precautions must be observed in all cases of suspected hepatitis until the diagnosis and hepatitis type are confirmed.

Immunization of persons exposed to the infection should be done as soon as possible. In the case of contact with hepatitis B, both hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) and HBV vaccine should be administered within 24 hours of skin-break contact and within 14 days of last sexual contact. For hepatitis A, immune globulin (IG) should be given within 2 weeks of exposure. In day care centers, IG should be given to all contacts (children and personnel).

TABLE 8.9 Diagnostic Testing for HIV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Saliva specimens may also be collected and are usually indicated in clinic settings or outreach environments—that is, point-of-care settings. The oral fluid HIV diagnostic kit can provide results in as little as 20 minutes; however, a positive test should be confirmed with more specific testing, such as Western blot or IFA. See Chart 8.1 for additional applications for oral testing.

Use a special testing kit such as the commercial OraSure HIV-1 Oral Specimen Collection Device (OraSure Technologies, Inc., Bethlehem, PA). The kit includes a specially treated cotton pad on a nylon stick and a vial containing preservative solution. Salt solution in the pad facilitates absorption of the required fluid.

Place the cotton pad between the lower cheek and gum, rub back and forth until moistened, and leave in place for 2 minutes. Remove specially treated pad and place it in the vial of special antimicrobial preservative solution. Place specimen container in a biohazard bag and transport to laboratory.

The Omni-SAL (Saliva Diagnostic Systems, Brooklyn, NY) device employs a different collection method in which a cotton pad is placed under the tongue. An indicator in the collecting device changes color when an adequate amount of oral fluid has been collected.

1. HIV-1 and HIV-2 |

2. Viral hepatitis A, B, and C |

3. Helicobacter pylori |

4. Measles |

5. Mumps |

6. Rubella |

7. Syphilis |

8. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) |

9. Autoimmune diseases |

10. Cancer (carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA], prostate-specific antigen [PSA], CA 125) |

11. Diabetes types 1 and 2 |

12. Therapeutic drug and hormone management and detection of other drugs |

A positive test is associated with viral replication and appearance of HIV antibodies (IgM, IgG).

A positive ELISA that fails to be confirmed by Western blot or IFA should not be considered negative, especially in the presence of symptoms or signs of AIDS. Repeat testing in 3 to 6 months is suggested.

A positive result may occur in noninfected persons because of unknown factors.

Negative tests tend to rule out AIDS in high-risk patients who do not have the characteristic opportunistic infections or tumors.

An HIV infection is described as a continuum of stages that range from the acute, transient, mononucleosis-like syndrome associated with seroconversion to asymptomatic HIV infection to symptomatic HIV infection and, finally, to AIDS. AIDS is end-stage HIV infection.

Treatments are more effective and less toxic when begun early in the course of HIV infection.

HIV PCR method to determine viral load may be performed during HIV treatment to monitor patient prognosis and treatment.

Diagnosis of HIV in neonates is difficult because maternally acquired antibodies may be present until the child is 18 months of age. Additionally, PCR to detect antigen is usually not successful until the child is 6 months of age.

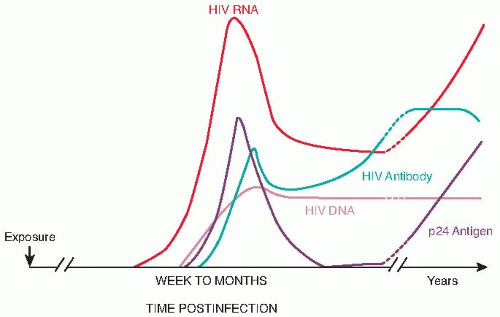

Nonreactive HIV test results occur during the acute stage of disease when the virus is present but antibodies are not sufficiently developed to be detected. It may take up to 6 months for the test

result to become positive. During this stage, the test for the HIV antigen may confirm an HIV infection (Fig. 8.1).

Test kits for HIV are extremely sensitive. As a result, nonspecific reactions may occur if the tested person has been previously exposed to HIV human cells or the growth media.

An informed, witnessed consent form must be properly signed by any person being tested for HIV/AIDS. This consent form must accompany the patient and the specimen (see Appendix F for sample form).

It is essential that counseling precedes and follows the HIV antibody test. This test should not be performed without the subject’s informed consent, and persons who need to access results legitimately must be mentioned. Discussion of the clinical and behavioral implications derived from the test results should address the accuracy of the test and should encourage behavioral modifications (e.g., sexual contact, shared needles, blood transfusions).

Assess frequency and intensity of symptoms: elevated temperature, anxiety, fear, diarrhea, neuropathy, nausea and vomiting, depression, and fatigue.

Infection control measures mandate use of standard precautions (see Appendix A).

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Issues of confidentiality surround HIV testing. Access to test results should be given judiciously on a need-to-know basis unless the patient specifically expresses otherwise. Interventions to block general computer access to this information are necessary; each health care facility must determine how best to accomplish this.

Conversely, health care workers directly involved with the care of an HIV/AIDS patient have a right to know the diagnosis so that they may protect themselves from exposure.

All results, both positive and negative, must be somehow entered in the patient’s health care records while maintaining confidentiality. People are more likely to test voluntarily when they trust that inappropriate disclosure of HIV testing information will not occur. Long-term implications include potential loss of jobs, housing, insurance coverage, and personal relationships.

The clinician must sign a legal form stating that the patient has been informed regarding test risks.

A person who exhibits HIV antibodies is presumed to be HIV infected; appropriate counseling, medical evaluation, and health care interventions should be discussed and instituted.

Positive test results must be reported to the state and federal public health authorities according to prescribed state regulations and protocols.

Anonymous testing and reporting is available, such as commercial home tests.

Interpret test outcomes. Explain significance of test results along with CD4+ cell counts. Advise patient that screening tests must be confirmed before the results are reported as HIV reactive. Provide options for immediate counseling if necessary. Explain treatment with potent antiviral drugs and protease inhibitors. The International AIDS Society-USA has recommended starting treatment with antiretroviral drugs if the CD4 cell count is <350/µL but before it reaches 200/µL. Plasma HIV-1 RNA level should be checked every 4 to 8 weeks until it is nondetectable and thereafter three to four times per year. Recently, the FDA has approved darunavir ethanolate for the treatment of HIV in antiretroviral treatment-experienced patients.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

usually not recommended when the patient is >6 months of age. Unlike IgG class antibodies, IgM antibodies are larger molecules and cannot cross the placenta, thus determining that the infant has an active form of the disease.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions. Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Follow-up testing may be required.

When testing for IgG antibody, seroconversion between acute and convalescent sera is considered strong evidence of a current or recent infection. The recommended interval between an acute and convalescent sample is 10 to 14 days.

A serum specimen taken very early during the acute stage of infection may contain levels of IgG antibody below 10 IU/mL.

Although the presence of IgM antibody suggests current or recent infection, low levels of IgM may occasionally persist for more than 12 months after infection or immunization. Passively acquired rubella antibody levels (IgG) in the infant (which can cross the placenta because of their smaller molecular size) decrease markedly within 2 to 3 months after infection.

IgM is detectable soon after clinical symptoms occur and reaches peak levels at 10 days.

Assess patient’s test knowledge. Explain test purpose and procedure. Advise pregnant women that rubella infection acquired in the first trimester of pregnancy is associated with an increased incidence of miscarriage, stillbirth, and congenital abnormalities.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcome and counsel appropriately. Advise women of childbearing age who test negative to be immunized before becoming pregnant. Immunization is contraindicated during pregnancy. Patients who test positive are naturally immune to further rubella infections.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions. Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Follow-up testing may be required.

When testing for IgG antibody, seroconversion between acute and convalescent sera is considered strong evidence of a current or recent infection. The recommended interval between an acute and convalescent sample is 10 to 14 days.

Although the presence of IgM antibody suggests current or recent infection, low levels of IgM may occasionally persist for more than 12 months after infection or immunization.

IgM antibody response is detectable 2 to 3 weeks after appearance of the rash.

Assess patient’s test knowledge. Explain test purpose and procedure. Advise pregnant women that measles poses a high risk for serious complications and may be linked to premature delivery or spontaneous abortion.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcome and counsel appropriately. Advise women of childbearing age who test negative to be immunized before becoming pregnant. Inform patients who test positive that they are naturally immune to further measles infection.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed posttest care.

symptom in mumps is usually sufficient to preclude confirmation by serology. However, one third of mumps infections are subclinical and may require viral isolation to confirm mumps infection. Infection with mumps virus, whether symptomatic or subclinical, is generally thought to offer lifelong immunity.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. The optimal time to collect serum in unvaccinated persons is 3 to 5 days after they become symptomatic. This is necessary because, in unvaccinated patients, IgM may not be present until 5 days after onset of symptoms, typically peaks in 7 days, and may be present for up to 6 weeks or more. Observe standard precautions. Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

The CDC recommends that a blood specimen, buccal/oral swab, and urine be collected from individuals with clinical suspicion of mumps. Buccal/oral and urine specimens should be collected 3 to 5 days after the onset of symptoms. To collect the buccal/oral specimen, massage the parotid gland for 30 seconds and then swab the area between the cheek and gum by sweeping the swab near the upper to lower molar area.

Follow-up testing may be required.

When testing for IgG antibody, seroconversion between acute and convalescent sera is considered strong evidence of a current or recent infection.

The recommended interval between an acute and convalescent sample is 10 to 14 days.

The clinical case definition of mumps is an acute onset of unilateral or bilateral tender, self-limiting swelling of the parotid gland (or other salivary glands) with or without other apparent cause lasting 2 or more days. A probable case is one that meets the clinical case definition without serologic or virologic testing, whereas a confirmed case meets the clinical definition and is laboratory confirmed.

Assess patient’s test knowledge. Explain test purpose and procedure.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcome and counsel appropriately.

If there are no complications, typically, mumps is treated with bed rest and medications to reduce pain and fever, such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Patients younger than 20 years should not be given aspirin because of its link to Reye’s syndrome.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions. Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Follow-up testing may be required.

When testing for IgG antibody, seroconversion between acute and convalescent sera is considered strong evidence of a current or recent infection. The recommended interval between an acute and convalescent sample is 10 to 14 days.

Whereas the presence of IgM antibody suggests a current or recent infection, low levels of IgM may occasionally persist for more than 12 months after infection or immunization.

Immunosuppressed patients in hospitals may contract severe nosocomial infections from others infected with VZV. Therefore, serologic screening of direct health care providers (e.g., physicians, nurses) is necessary to avoid spread of infection.

Assess patient’s test knowledge. Explain test purpose and procedure. Advise pregnant women that VZV poses a high risk for congenital disease in the infant.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcome and counsel appropriately. Inform patients who test positive for VZV IgG that they are naturally immune to chickenpox, but the virus can be reactivated and cause shingles at a later time.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions. Place specimen in biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

It is recommended that posttransplantation titers be monitored at weekly intervals, particularly following bone marrow transplantation.

Infants who acquire CMV during primary infection of the mother are prone to develop severe cytomegalic inclusion disease (CID). CID may be fatal or may cause neurologic sequelae such as mental retardation, deafness, microcephaly, or motor dysfunction.

Transfusion of CMV-infected blood products or transplantation of CMV-infected donor organs may produce interstitial pneumonitis in an immunocompromised recipient.

When testing for IgG antibody, seroconversion or a significant rise in titer between acute and convalescent sera may indicate presence of a current or recent infection.

Although the presence of IgM antibodies suggests current or recent infection, low levels of IgM antibodies may occasionally persist for more than 12 months after infection.

Explain test purpose and procedure.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcomes (see Interpreting Results of Immunologic Tests) and counsel appropriately.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions.

Place specimen in biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Follow-up testing is usually required.

Most persons in the general population have been infected with HSV by 20 years of age. After the primary infection, antibody levels fall and stabilize until a subsequent infection occurs.

Diagnosis of current infection is related to determining a significant increase in antibody titers between acute-stage and convalescent-stage blood samples.

Serologic tests cannot indicate the presence of active genital tract infections. Instead, direct examination with procurement of lesion cultures should be done.

Newborn infections are acquired during delivery through the birth canal and may present as localized skin lesions or more generalized organ system involvement.

Assess patient’s knowledge regarding the test. Explain test purpose and procedure.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcome; see Interpreting Results of Immunologic Tests. Advise pregnant women that the newborn may be infected during birth when active genital area infection is present. Explain need for repeat testing.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions.

Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Positive results (antibodies to HTLV-I) occur in the presence of HTLV-I infection. Infection transmitted to recipients of HTLV-I-infected blood is well documented.

The presence of antibodies to HTLV-I bears no relation to the presence of antibodies to HIV-1; its presence does not put a person at risk for HIV/AIDS, but they often occur concurrently because of similar risk factors.

HTLV-I is endemic to the Caribbean, Southeastern Japan, and some areas of Africa.

In the United States, HTLV-I has been detected in persons with ATL, intravenous drug users, and healthy persons as well as in donated blood products. Transmission can also take place through ingestion of breast milk, sexual contact, and sharing of contaminated intravenous drug paraphernalia.

Assess patient’s knowledge about test. Explain test purpose and procedure.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test results; see Interpreting Results of Immunologic Tests. Counsel patient appropriately.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions.

Place sample in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Positive parvovirus B-19 infection has been implicated in aplastic anemia associated with organ transplantation. It is recommended, therefore, that this test be included in the serologic assessment of prospective organ donors.

Immunocompromised patients may have a delayed or absent antibody response. It is recommended that parvovirus DNA detection by PCR be considered.

Assess patient’s knowledge regarding test. Explain purpose and blood test procedure. Advise any prospective organ donor that this test is part of a panel of tests performed before organ donation to protect the organ recipient from potential infection.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Interpret test outcome (see Interpreting Results of Immunologic Tests) and explain significance of results.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

If the suspect animal exhibits abnormal behavior, standard procedure is to euthanize the animal and examine its brain for Negri body inclusions in the neurons.

Rabies testing is usually performed in a public health laboratory.

An elevated titer in humans indicates an adequate response after immunization. A rabies titer of 1:16 or greater is considered protective.

Pre-exposure vaccination should be offered to individuals in high-risk groups, such as veterinarians, animal handlers, or international travelers if they are likely to come in contact with rabid animals and medical care is limited.

Postexposure vaccination should be administered to previously vaccinated individuals if exposed to rabies.

Postexposure prophylaxis is considered a medical urgency, and each situation should be evaluated by trained medical personnel and in consultation with public health officials. The individual should not be vaccinated unless the animal develops clinical signs of rabies during a 10-day observation period. If the animal is rabid, the person should be vaccinated immediately.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions.

Place in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Antibodies to Coccidioides, Blastomyces, and Histoplasma appear early in the course of the disease (weeks 1 to 4) and then disappear.

Negative fungal serology does not rule out the possibility of a current infection.

CF titers ≥1:8 are considered presumptive of infection.

Antibodies to fungi may be found in blood samples from apparently healthy people.

When testing for blastomycosis, cross-reactions with histoplasmosis may occur.

More than 50% of patients having active blastomycosis yield a negative result by CF.

Recent histoplasmosis skin tests must be avoided because they cause elevated CF test results, which may be due to the stimulation from the skin test and not the systemic infection.

Explain test purpose and procedure.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Remember that specimens for culture of the organism may also be required.

Interpret test results; see Interpreting Results of Immunologic Tests. Counsel appropriately.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. Observe standard precautions.

Place in a biohazard bag for transfer to the laboratory.

A titer ≥1:8 by latex agglutination (LA) or CIE for Candida antigen indicates systemic infection.

A fourfold rise in titers of paired blood samples 10 to 14 days apart indicates acute infection.

Patients on long-term intravenous therapy treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics and diabetic patients commonly have disseminated infections caused by Candida albicans. The disease also occurs in bottle-fed newborns and in the urinary bladder of catheterized patients.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis, common in late pregnancy, can transmit candidiasis to the infant through the birth canal.

Approximately 25% of the normal population tests positive for the presence of Candida.

Cross-reaction can occur with latex agglutination testing in persons who have cryptococcosis or tuberculosis.

Positive results can occur in the presence of mucocutaneous candidiasis or severe vaginitis.

Explain test purpose and procedure.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Specimens for culture of the organism may also be required.

Interpret test results; see Interpreting Results of Immunologic Tests. Counsel patient appropriately. Repeat testing is usually indicated.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. CSF can also be tested. Observe standard precautions.

Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Positive test results are associated with pulmonary infections in compromised patients and Aspergillus infections of prosthetic heart valves.

If blood serum exhibits one to four bands using immunodiffusion, aspergillosis is strongly suspected. Weak bands suggest an early disease process or hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Best use of the CF test is with paired sera taken 3 weeks apart to detect a rise in titer against a single antigen.

Explain test purpose and procedure.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Specimens for culture of the organism may also be required.

Interpret test outcome; see Interpreting Results of Immunologic Tests. Counsel appropriately.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

or are being treated with steroid therapy. Infection with C. neoformans has long been associated with Hodgkin’s disease and other malignant lymphomas. In fact, C. neoformans, in conjunction with malignancy, occurs to such a degree that some researchers have raised the question regarding the possible etiologic relation between the two diseases. Tests ordered for this disease include latex agglutination testing for antigens or antibodies.

Collect a 7-mL blood serum sample in a red-topped tube. A 2-mL spinal fluid sample may also be used. Observe standard precautions.

Place specimen in a biohazard bag for transport to the laboratory.

Positive C. neoformans tests are associated with infections of the lower respiratory tract through inhalation of aerosols containing C. neoformans cells disseminated by the fecal droppings of pigeons.

TA titers ≥1.2 are suggestive of infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree