Immunodeficiency Disorders

INTESTINAL HOST DEFENCES

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract must digest and selectively absorb nutrients, while at the same time excluding large amounts of potentially harmful ingested substances such as microorganisms and toxins.1, 2, 3, 4 Both immune and nonimmune defense mechanisms are important for intestinal host defense.3, 5, 6, 7, 8 This defense is provided within the lumen by secretory IgA (originating from the intestine or bile) and within the mucosa by lymphocytes (mucosal alpha-beta and gammadelta T cells),5, 6, 8 plasma cells, and macrophages.9 Secretory IgA has been likened to antiseptic paint, which lines the bowel mucosa, acting as a protective layer. It has four antigen-combining sites and is very efficient at agglutinating bacteria and viruses and preventing their adherence to mucosal surfaces. In addition, IgA interferes with the absorption of many macromolecules by combining with food. This helps prevent harmful systemic immune responses. The antigens (particulate and soluble products) that do escape the action of secretory IgA and penetrate the surface epithelium may form immune complexes, which can be cleared by the liver and excreted in the bile. Alternatively, they may be cleared by locally sensitized lymphocytes, by combination with preformed antibodies, or by ingestion by macrophages.5

Much of the work on gut immunology has centered on the role of humoral immunity on gut defense mechanisms. However, B-cell function is often under the control of T cells.5, 10, 11 Intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), most of which are of T-cell (CD-8) type, have an important cytotoxic action. Cell-mediated immunity appears to play an important role in

fungal infections such as candidiasis, certain viral diseases, and parasitic infections, whereas humoral immunity seems more important in protecting against run-of-the-mill enteric bacterial and viral infections.12

fungal infections such as candidiasis, certain viral diseases, and parasitic infections, whereas humoral immunity seems more important in protecting against run-of-the-mill enteric bacterial and viral infections.12

A variety of nonimmunologic factors contribute to gut host defense. They include the physical integrity of the mucosa/mucosal barrier (intestinal permeability); intestinal mucus, which may impair antigen binding and allow antigen degradation by intestinal enzymes; resident microbial flora; acid and pepsin, which cause bacterial and dietary antigen degradation; bile acids, which suppress microbial proliferation; and bowel motility. The latter produces regular cleansing of the intestinal tract.13, 14, 15

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY OF THE GI IMMUNE SYSTEM

Normal Distribution of Gut-associated Lymphoid Tissue

Lymphoid tissue is normally abundant throughout the GI mucosa (including IELs) with the exception of the stomach and in fact is the largest lymphoid organ in the body.8 In the stomach, there are almost no lymphocytes and plasma cells within the gastric fundus and body and only a few within the antrum and cardia. The lymphoid tissue first appears in the lamina propria of the bowel at 10 weeks16 and by 14 weeks lymphoid follicles develop. Plasma cells appear at birth but are very scanty.16 The lymphoid tissue is arranged in three forms:

1. As IELs, throughout the GI tract, including the esophagus.

2. As a diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, which is distributed evenly throughout the intestinal mucosa of the small and large intestines.

3. As lymphoid nodules. There are essentially two types:

a. Solitary lymphoid nodules present throughout the GI tract but most numerous in the distal colon.17

b. Aggregates of lymphoid nodules, which occur in the appendix and small intestine. In the small intestine, these aggregates are referred to as Peyer’s patches and are most frequent in the distal ileum.18

The lymphoid tissue in the ileocecal valve is unique in that it is arranged circumferentially around the valve. The mesenteric lymph nodes are also usually considered part of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). In common with the gut, mesenteric lymph nodes are exposed to considerable antigenic material via the lymphatic flow from the small and large intestines and are populated by predominantly IgA precursor B-cell lymphocytes.

The Diffuse Lymphoid Tissue This tissue is contained in two separate compartments, namely, intraepithelial and intramucosal.19

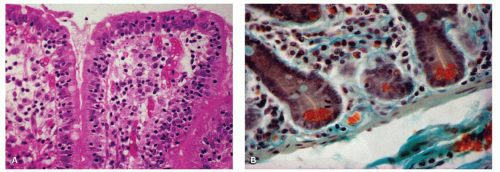

INTRAEPITHELIAL LYMPHOCYTES. These cells are located within the surface epithelial layer of the mucosa, the so-called IELs (Fig. 3-1A). They occur predominantly in the basal portion of the epithelial layer, between the epithelial cells and the basement membrane.20, 21

Although they appear to be few in number in any one section (at the range of 10-25 per 100 epithelial cells in the small bowel and ˜5 per 100 epithelial cells in the colon),22, 23, 24 when the entire intestine is considered, they are in fact very numerous and are said to equal in aggregate the number of lymphocytes found in the spleen. Histologically, the IELs consist of dense nuclei with minimal cytoplasm and do not have any epithelial attachment. The predominant phenotype is the cytotoxic T cell expressing αβ T-cell receptors, which are CD3+, CD8+, CD103+, CD4−, and CD5−. A smaller population (10%-15%) consists of T cells expressing γδ T-cell receptors that are negative for both CD4 and CD8. A third population of CD56+ IELs is also recognized that are virtually undetectable in normal mucosa. They have T-cytotoxic and natural killer (NK) properties.20, 25 The IELs overlying the lymphoid follicles consist predominantly of B cells. In addition, other intraepithelial cells such as macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils may also be present.16, 23, 26 IELs are greatly increased in several diseases, such as celiac sprue, tropical sprue, lymphocytic colitis, and collagenous colitis. They are typically not increased in inflammatory bowel disease.23 In inflammatory states, neutrophils and eosinophils may also enter this compartment.27

Although they appear to be few in number in any one section (at the range of 10-25 per 100 epithelial cells in the small bowel and ˜5 per 100 epithelial cells in the colon),22, 23, 24 when the entire intestine is considered, they are in fact very numerous and are said to equal in aggregate the number of lymphocytes found in the spleen. Histologically, the IELs consist of dense nuclei with minimal cytoplasm and do not have any epithelial attachment. The predominant phenotype is the cytotoxic T cell expressing αβ T-cell receptors, which are CD3+, CD8+, CD103+, CD4−, and CD5−. A smaller population (10%-15%) consists of T cells expressing γδ T-cell receptors that are negative for both CD4 and CD8. A third population of CD56+ IELs is also recognized that are virtually undetectable in normal mucosa. They have T-cytotoxic and natural killer (NK) properties.20, 25 The IELs overlying the lymphoid follicles consist predominantly of B cells. In addition, other intraepithelial cells such as macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils may also be present.16, 23, 26 IELs are greatly increased in several diseases, such as celiac sprue, tropical sprue, lymphocytic colitis, and collagenous colitis. They are typically not increased in inflammatory bowel disease.23 In inflammatory states, neutrophils and eosinophils may also enter this compartment.27

Lymphocytes are also present within the esophageal squamous epithelium. They occur primarily within the suprabasal portion of the mucosa, interdigitating between the squamous cells, and phenotypically consist of CD3/CD8 cytotoxic suppressor cells.28

INTRAMUCOSAL CELLULAR INFILTRATE (LYMPHOCYTES, PLASMA CELLS, EOSINOPHILS, MAST CELLS, MACROPHAGES, ETC.). The cells consist primarily of numerous lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. In addition, a heterogeneous group of other cells are also present in smaller numbers, namely, eosinophils, mast cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, rare basophils, and T lymphocytes (Fig. 3-1B). The latter consist primarily of helper inducer cells.29

Intramucosal lamina propria. With regard to lymphocytes, the lamina propria is the largest compartment of GI lymphocytes, the number being in the range of several thousands per square millimeter.

They are located primarily in the crypt region and less frequently in the villi in the small bowel. The majority of plasma cells, many of which contain Russell bodies, consist primarily of IgA-containing cells, followed by IgM, IgG, and IgE.25 IgD-containing plasma cells are exceedingly sparse in the normal GI tract.

Neutrophils are exceedingly rare/absent in the normal lamina propria. However, eosinophils are generally present, ranging up to 200 per mm2.30 The number of eosinophils in the colon is highest on the right side and lowest in the rectum. The number of eosinophils in the lamina propria also varies geographically according to latitude, as the farther north one goes in the United States, the fewer eosinophils one finds in normal colon biopsies.31

Mucosal mast cells. The mast cells occur predominantly in the lamina propria as well as the submucosa and appear to be more common in the ileum than the jejunum, up to about 750 cells per mm2.32 In the mucosa, they are primarily within the superficial half of the lamina propria. They have proved to be more numerous than was previously thought, mainly because they were previously missed in routinely prepared tissue sections. In animal studies, there is great heterogeneity among mast cells in that intestinal mast cells are morphologically and functionally distinct from peritoneal and systemic mast cells.33 The same type of difference may also exist in man, but this remains to be proven.34 Mast cells have physiologic regulatory effects as well as pathologic effects.35 Their function was previously thought to be confined to IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions. However, recent animal studies have shown that they are also involved in the late-phase components of allergic reactions, delayed-onset hypersensitivity, and regulation of immune responses. With regard to the functional activity of the mast cells, a variety of substances are released from the cells, leading to a number of factors such as blood flow regulation, endothelial and epithelial permeability, angiogenesis, mucosal secretion, and intestinal motility.32 Moreover, mast cells can express direct cytotoxic activity and can potentiate eosinophil and macrophage cytotoxicity.34 In certain conditions, such as nematode infections, gastritis, celiac sprue, idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease, and irritable bowel disease, mast cell numbers may be markedly increased in concert with other inflammatory cells.36

Histologically, Carnoy’s fixative37 was found to be better than formalin for identifying mucosal mast cells. Recently, however, a number of immunostains have been helpful in identifying these cells such as mast cell tryptase, CD117 (C kit),38 and CD68 (KP-1).39 These stains seem to obviate the need for any special fixatives as they work well on formalin-fixed tissue.

Mucosal lamina propria macrophages Macrophages are present in small numbers within the lamina propria, mainly beneath the top of intestinal villi and within the surface of the large intestine. Mucosal macrophages at the base of the lamina propria are generally less numerous, occurring primarily in the stomach and small intestine. Morphologically, they may be readily missed if not deliberately searched for. However, they increase greatly in number in inflammatory conditions. Functionally, they seem to play an important role in the intestinal mucosal immune system and also in inflammatory responses.40, 41

The Solitary and Aggregate Lymphoid Follicles (Peyer’s Patch)

SOLITARY LYMPHOID FOLLICLES. These are abundant throughout the small and large bowel but are most numerous in the distal colon.17 It has been estimated that there are several thousand follicles in the small intestine and up to 20,000 in the colon. The number of follicles within the stomach is very few. The structure and function of the lymphoid follicles appear to be similar to those of the Peyer’s patches.17, 42

PEYER’S PATCHES. Peyer’s patches are aggregated nodules of lymphoid follicles, which are most numerous in the distal ileum,18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree