Frank Hope has walked with a limp since contracting polio in 1950. When he watches his daughter run after her young toddler, he feels a sense of gratitude that the era of vaccination has protected his child and grandchild from such a disabling infection. He recalls the excitement that gripped the nation as the Salk polio vaccine was first tested and then adopted into widespread use. In Frank’s mind, these types of scientific breakthroughs attest to the wonders of the US health care system.

Frank’s grandson attends a day care program. Ruby, a 3-year-old girl in the program, was recently hospitalized for a severe asthma attack complicated by pneumococcal pneumonia. She spent 2 weeks in a pediatric intensive care unit, including several days on a respirator. Ruby’s mother works full time as a bus driver while raising three children. She has comprehensive private health insurance through her job but finds it difficult to keep track of all her children’s immunization schedules and to find a physician’s office that offers convenient appointment times. She takes Ruby to an evening-hours urgent care center when Ruby has some wheezing but never sees the same physician twice. Ruby never received all her pneumococcal vaccinations or consistent prescription of a steroid inhaler to prevent a severe asthma attack. Ruby’s mother blames herself for her child’s hospitalization.

INTRODUCTION

People in the United States rightfully take pride in the technologic accomplishments of their health care system. Innovations in biomedical science have almost eradicated scourges such as polio and measles and have allowed such marvels as organ transplantation, “knifeless” gamma-ray surgery for brain tumors, and intensive care technology that saves the lives of children with asthma complicated by pneumonia. Yet for all its successes, the health care system also has its failures. For example, asthma is a leading cause of hospitalization in childhood. Proper health care can markedly reduce the frequency of severe asthma symptoms and of asthma hospital admissions. In cases such as Ruby’s, the failure to prevent severe asthma flare-up is not related to financial barriers, but rather reflects organizational problems, particularly in the delivery of primary care and preventive services.

The organizational task facing all health care systems is one of “assuring that the right patient receives the right service at the right time and in the right place” (Rodwin, 1984). An additional criterion could be “… and by the right caregiver.” The fragmented care Ruby received for her asthma is an example of this challenge. Who is responsible for planning and ensuring that every child receives the right service at the right time? Can an urgent care center or an in-store clinic at Wal-Mart designed for episodic needs be held accountable for providing comprehensive care to all patients passing through its doors? Should parents be expected to make appointments for routine visits at medical offices and clinics, or should public health nurses travel to homes and day care centers to provide preventive services out in the community? What is the proper balance between intensive care units that provide life-saving services to critically ill patients and primary care services geared toward less dramatic medical and preventive needs?

The previous chapters have emphasized financial transactions in the health care system. In this chapter and the following one, the organization of the health care system will be the main focus. While considerable debate has dwelled on how to improve financial access to care, less emphasis has been given to the question “access to what?” In this chapter, organizational systems will be viewed through a wide-angle lens, with emphasis on such broad concepts as the relationship between primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of care, and the influence of the biomedical paradigm and medical professionalism in shaping US health care delivery. In Chapter 6, a zoom lens will be used to focus on specific organizational models that have appeared (often only to disappear) in this country over the past century.

MODELS OF ORGANIZING CARE

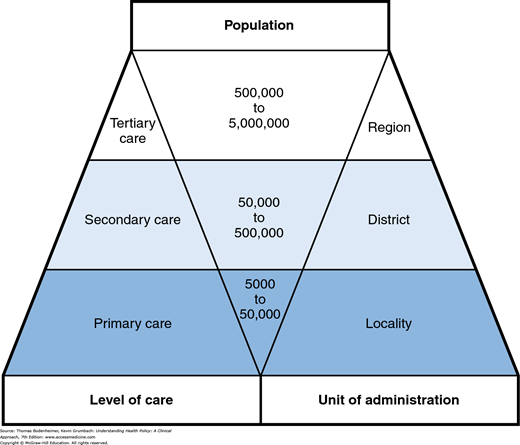

One concept is essential in understanding the topography of any health care system: the organization of care into primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. In the Lord Dawson Report, an influential British study written in 1920, the author (1975) proposed that each of the three levels of care should correspond with certain unique patient needs.

Primary care involves common health problems (e.g., sore throats, diabetes, arthritis, depression, or hypertension) and preventive measures (e.g., vaccinations or mammograms) that account for 80% to 90% of visits to a physician or other caregiver.

Secondary care involves problems that require more specialized clinical expertise such as hospital care for a patient with acute renal failure.

Tertiary care, which lies at the apex of the organizational pyramid, involves the management of rare disorders such as pituitary tumors and congenital malformations.

Two contrasting approaches can be used to organize a health care system around these levels of care: (1) the carefully structured Dawson model of regionalized health care and (2) a more free-flowing model.

One approach uses the Dawson model as a scaffold for a highly structured system. This model is based on the concept of regionalization: the organization and coordination of all health resources and services within a defined area (Bodenheimer, 1969). In a regionalized system, different types of personnel and facilities are assigned to distinct tiers in the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels, and the flow of patients across levels occurs in an orderly, regulated fashion. This model emphasizes the primary care base and a population-oriented framework for health planning.

An alternative model allows for more fluid roles for caregivers, and more free-flowing movement of patients, across all levels of care. This model tends to place a higher value on services at the tertiary care apex than at the primary care base.

Although most health care systems embody elements of both models, some gravitate closer to one polarity or the other. The traditional British National Health Service (NHS) and some large integrated delivery systems in the United States resemble the regionalized approach, while US health care as a whole traditionally followed the more dispersed format.

Basil, a 60-year-old man living in a London suburb, is registered with Dr. Prime, a general practitioner in his neighborhood. Basil goes to Dr. Prime for most of his health problems, including hay fever, back spasms, and hypertension. One day, he experiences numbness and weakness in his face and arm. By the time Dr. Prime examines him later that day, the symptoms have resolved. Suspecting that Basil has had a transient ischemic attack, Dr. Prime prescribes aspirin and refers him to the neurologist at the local hospital, where a carotid artery sonogram reveals high-grade carotid stenosis. Dr. Prime and the neurologist agree that Basil should make an appointment at a London teaching hospital with a vascular surgeon specializing in head and neck surgery. The surgeon recommends that Basil undergo carotid endarterectomy on an elective basis to prevent a major stroke. Basil returns to Dr. Prime to discuss this recommendation and inquires whether the operation could be performed at a local hospital closer to home. Dr. Prime informs him that only a handful of London hospitals are equipped to perform this type of specialized operation. Basil schedules his operation in London and several months later has an uncomplicated carotid endarterectomy. Following the operation, he returns to Dr. Prime for his ongoing care.

The British NHS has traditionally typified a relatively regimented primary—secondary—tertiary care structure (Fig. 5-1).

For physician services, the primary care level is virtually the exclusive domain of general practitioners (commonly referred to as GPs), who practice in small- to medium-sized groups and whose main responsibility is ambulatory care. About half of all physicians in the United Kingdom are GPs.

The secondary tier of care is occupied by physicians in such specialties as internal medicine, pediatrics, neurology, psychiatry, obstetrics and gynecology, and general surgery. These physicians are located at hospital-based clinics and serve as consultants for outpatient referrals from GPs, in turn routing most patients back to GPs for ongoing care needs. Secondary-level physicians also provide care to hospitalized patients.

Tertiary care subspecialists such as cardiac surgeons, immunologists, and pediatric hematologists are located at a few tertiary care medical centers.

Hospital planning followed the same regionalized logic as physician services. District hospitals were local facilities equipped for basic inpatient services. Regional tertiary care medical centers handled highly specialized inpatient care needs.

Planning of physician and hospital resources within the traditional NHS occurred with a population focus. GP groups provided care to a base population of 5,000 to 50,000 persons, depending on the number of GPs in the practice. District hospitals had a catchment area population of 50,000 to 500,000, while tertiary care hospitals served as referral centers for a population of 500,000 to 5 million (Fry, 1980).

While this regionalized structure has recently become more fluid (Chapter 14), patient flow still moves in a stepwise fashion across the different tiers. Except in emergency situations, all patients are first seen by a GP, who may then steer patients toward more specialized levels of care through a formal process of referral. Patients may not directly refer themselves to a specialist.

While nonphysician health professionals, such as nurses, play an integral role in staffing hospitals at the secondary and tertiary care levels, especially noteworthy is the NHS’ multidisciplinary approach to primary care. GPs work in close collaboration with practice nurses (similar to nurse practitioners in the United States), home health visitors, public health nurses, and midwives (who attend most deliveries in the United Kingdom). Such teamwork, along with accountability for a defined population of enrolled patients and universal health care coverage, helps to avert such problems as missed childhood vaccinations. Public health nurses visit all homes in the first weeks after a birth to provide education and assist with scheduling of initial GP appointments. A national vaccination tracking system notifies parents about each scheduled vaccination and alerts GPs and public health nurses if a child has not appeared at the appointed time. As a result, more than 85% of British preschool children receive a full series of immunizations.

A number of other nations, ranging from industrialized countries in Scandinavia to developing nations in Latin America, have adopted a similar approach to organizing health services. In low-income nations, the primary care tier relies more on community health educators and other types of public health personnel than on physicians.

Polly Seymour, a 55-year-old woman with private health insurance who lives in the United States, sees several different physicians for a variety of problems: a dermatologist for eczema, a gastroenterologist for recurrent heartburn, and an orthopedist for tendinitis in her shoulder. She may ask her gastroenterologist to treat a few general medical problems, such as borderline diabetes. On occasion, she has gone to the nearby hospital emergency department for treatment of urinary tract infections. One day, Polly feels a lump in her breast and consults a gynecologist. She is referred to a surgeon for biopsy, which indicates cancer. After discussing treatment options with Polly, the surgeon performs a lumpectomy and refers her to an oncologist and radiation therapy specialist for further therapy. She receives all these treatments at a local hospital, a short distance from her home.

The US health care system has had a far less structured approach to levels of care than the British NHS. In contrast to the stepwise flow of patient referrals in the United Kingdom, insured patients in the United States, such as Polly Seymour, have traditionally been able to refer themselves and enter the system directly at any level. While many patients in the United Kingdom have a primary care physician (PCP) to initially evaluate all their problems, many people in the United States have become accustomed to taking their symptoms directly to the specialist of their choice.

One unique aspect of the US approach to primary care has been to broaden the role of internists and pediatricians. While general internists and general pediatricians in the United Kingdom and most European nations serve principally as referral physicians in the secondary tier, their US counterparts share in providing primary care. Moreover, the overlapping roles among “generalists” in the United States (family physicians, general internists, and general pediatricians) are not limited to the outpatient sector. PCPs in the United States have assumed a number of secondary care functions by providing substantial amounts of inpatient care. Only recently has the United States moved toward the European model that removes inpatient care from the domain of PCPs and assigns this work to “hospitalists”—physicians who exclusively practice within the hospital (Wachter & Goldman, 1996; Goroll & Hunt, 2015).

Including general internists and general pediatricians, the total supply of generalists amounts to approximately one-third of all physicians in the United States, a number well below the 50% or more found in the UK (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2014). To fill in the primary care gap, some physicians at the secondary and tertiary care levels in the United States have also acted as PCPs for some of their patients. In contrast to physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants are more likely to work in primary care settings and are a key component of the nation’s clinical workforce.

US hospitals are not constrained by rigid secondary and tertiary care boundaries. Instead of a pyramidal system featuring a large number of general community hospitals at the base and a limited number of tertiary care referral centers at the apex, hospitals in the United States each aspire to offer the latest in specialized care. In most urban areas, for example, several hospitals compete with each other to perform open heart surgery, organ transplants, radiation therapy, and high-risk obstetric procedures. The resulting structure resembles a diamond more than a pyramid, with a small number of hospitals (mostly rural) that lack specialized units at the base, a small number of elite university medical centers providing highly super-specialized referral services at the apex, and the bulk of hospitals providing a wide range of secondary and tertiary services in the middle.

Critics of the US health care system find fault with its “top-heavy” specialist and tertiary care orientation and lack of organizational coherence. Analyses of health care in the United States over the past half century abound with such descriptions as “a nonsystem with millions of independent, uncoordinated, separately motivated moving parts,” “fragmentation, chaos, and disarray,” and “uncontrolled growth and pluralism verging on anarchy” (Somers, 1972; Halvorson & Isham, 2003). The high cost of health care has been attributed in part to this organizational disarray. Quality of care may also suffer. For example, when many hospitals each perform small numbers of surgical procedures such as coronary artery bypass grafts, mortality rates are higher than when such procedures are regionalized in a few higher-volume centers (Gonzalez et al., 2014).

Defenders of the dispersed model reply that pluralism is a virtue, promoting flexibility and convenience in the availability of facilities and personnel. In this view, the emphasis on specialization and technology is compatible with values and expectations in the United States, with patients placing a high premium on direct access to specialists and tertiary care services, and on autonomy in selecting caregivers of their choice for a particular health care need. Similarly, the desire for the latest in hospital technology available at a convenient distance from home competes with plans to regionalize tertiary care services at a limited number of hospitals.

Dr. Billie Ruben completed her residency training in internal medicine at a major university medical center. Like most of her fellow residents, she went on to pursue subspecialty training, in her case gastroenterology. Dr. Ruben chose this career after caring for a young woman who developed irreversible liver failure following toxic shock syndrome. After a nerve-racking, touch-and-go effort to secure a donor liver, transplantation was performed and the patient made a complete recovery.

Upon completion of her training, Dr. Ruben joined a growing subspecialty practice at Atlantic Heights Hospital, a successful private hospital in the city. Even though the metropolitan area of 2 million people already has two liver transplant units, Atlantic Heights has just opened a third such unit, feeling that its reputation for excellence depends on delivering tertiary care services at the cutting edge of biomedical innovation. In her first 6 months at the hospital, Dr. Ruben participates in the care of only two patients requiring liver transplantation. Most of her patients seek care for chronic, often ill-defined abdominal pain and digestive problems. As Dr. Ruben begins seeing these patients on a regular basis, she starts to give preventive care and treat nongastrointestinal problems such as hypertension and diabetes. At times she wishes she had experienced more general medicine during her training.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree