History

Introduction

|

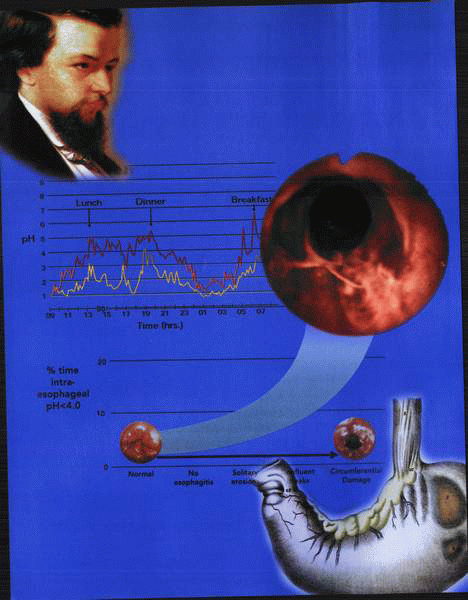

The elucidation of the pathobiology of acid peptic-related disease of the stomach and duodenum has accelerated dramatically in the last 20 years with the advent of scientific techniques that have facilitated the study of the cell biology of the gastric mucosa. The identification of cellular mechanisms has facilitated the development of therapeutic strategies capable of not only ameliorating the mucosal ulceration but also eradicating or abrogating the putative causes. Although acid and pepsin have long been recognized as pathogenic as regards the mucosa, it is only relatively recently that an infective component has been established as being of critical relevance to the etiology of gastric and duodenal ulcer disease.

Early management strategies thus focused briefly on the avoidance of acid-containing foods or substances containing capsaicin-related compounds. The use of bland diets was then augmented with the addition of neutralizing compounds and antacids. Unfortunately, such regimes lead to a significant decline in the quality of life and, in addition, to side effects (diarrhea, milk/alkali syndrome) associated with the use of excessive alkali and cationcontaining agents. The development of histamine-2 receptor antagonists and PPIs dramatically altered the efficacy of treatment, whereas the recognition of a bacterial component of the disease and its antibiotic eradication have more recently further amplified therapeutic gains. Within the context of the advance of the knowledge of regulatory mechanisms, various therapeutic strategies have evolved, leading to a substantial change in different types of intervention. In this respect, surgery has for the most part become obsolete as methods of decreasing acid secretion have evolved into more targeted and precise pharmacologic options. Nevertheless, the early surgical remedies were to a certain extent based on a reasonable grasp of the pathophysiology and the recognition of the need to effect relief of the problem of ulceration and its sequelae of pain, bleeding, perforation, and stenosis. The recognition that the ulcer was the crux of the issue led initially to the development of techniques to simply resect the area. Unfortunately, the rapid recurrence of the lesion obviated the use of this technique, and alternative strategies were evaluated to decrease the secretion of acid. The subsequent identification of the regulatory role of the vagus nerves to the stomach inspired a multiplicity of procedures to ensure their severance as well as the development of innumerable methods to overcome the subsequent negative alterations in gastric emptying. Further recognition that the fundus of the stomach contained the acid-secreting cells and the antrum—a

major component of the regulatory mechanism—led to the development of an extraordinary variety of permutations and combinations of antral and fundic resection. Such operations were devised with the view to variously removing the ulcer, decreasing gastrin stimulation, ablating neural stimulation, and decreasing the parietal cell mass.

major component of the regulatory mechanism—led to the development of an extraordinary variety of permutations and combinations of antral and fundic resection. Such operations were devised with the view to variously removing the ulcer, decreasing gastrin stimulation, ablating neural stimulation, and decreasing the parietal cell mass.

Sadly, they not only were plagued by operative morbidity and even mortality but also generated a panoply of symptomatology broadly designated as postgastrectomy syndromes, as the gut failed to accommodate the loss of neural innervation, pyloric function, and the severe neuroendocrine aberrations consequent on resective intervention.

At this juncture, it is rare to consider surgical intervention in acid peptic disease for anything less than a major complication; the evolution of the surgical strategies is worthy of consideration, if only to indicate the relative advantages of pharmacologic intervention as opposed to invasive modalities.

Early management of peptic ulcer disease

The earliest human texts address issues of the cosmos and the meanings of life, endlessly examining the nature of divinity, pantheism, and the fate of the soul. Throughout these erudite texts runs a common and fundamental issue speculated on both in metaphor and fact. The commonality of food, the stomach, and digestion can be noted in writings as divergent as those of the Sufi mystics, the Sephardic sages, philosophers of the Tang dynasty, or the Odes of the Mantuan Bard. Food and its digestion represent a theme of universal interest surpassed only by preoccupation with the ephemeral concept of love. Homo est quod est: Man is what he eats. It is therefore no wonder that the subject of digestion has been a matter of concern to doctors and their patients for as long as records exist. Unfortunately, little rational therapeutic intervention was available for the treatment of gastric disorders. Indeed, up until the late nineteenth century, the stomach was often not clearly recognized as a source of symptoms. From the earliest times, chalk, charcoal, and slop diets had been noted to provide symptomatic relief from dyspepsia.

In the seventeenth century, chalk and pearl juleps were used for infant gastric disorders, but little comment was made about adult problems except by Sydenham, who wrote about gout and dysentery. Jan Heurne, the first proponent of bedside teaching, left a posthumous pamphlet on the diseases of the stomach in 1610. Similarly, Martin Harmes and Ferriol, in 1684 and 1668, respectively, produced books on diseases of the stomach and intestines. In 1664, Swalbe published a long satire on “the quarrels and opprobria of the stomach” (prosopopoia). The favorite theme of the seventeenth-century physicians was the dyspepsia due to gastric atony implicit in the title De imbecilitate ventriculi. This term was continued into the eighteenth century, when it was equated with the “hectic stomach” (Arnold, 1743) and later with the term of “embarras gastrique,” used by the French physicians.

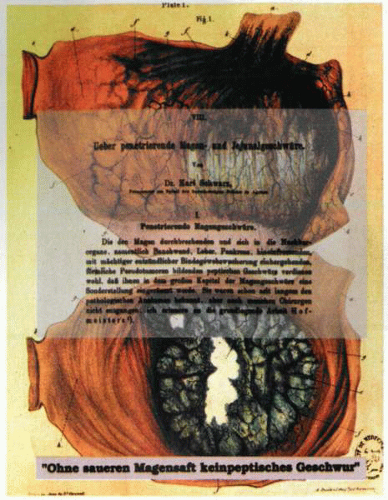

Throughout the eighteenth century, there were various descriptions of gastric and intestinal diseases, but no specific and logical remedies were recorded. The doctrine of acidity was widespread and prevalent, and the general literature of dyspepsia was large. Thus, in 1754, Joseph Black, writing on the subject of carbon dioxide, commented on De humore acido a cibo orto. In 1835, in Paris, Cruveilhier had written extensively on the pathology of peptic ulcer, and the condition was referred to as Cruveilhier’s disease. Yet, in all these tomes, little specific therapy, apart from dietary adjustments or homeopathic remedies, is apparent.

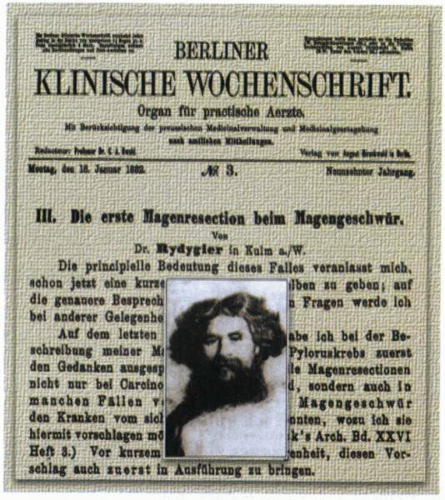

Ludwig Rydiger of Chelmo, on November 16, 1880, performed the second documented gastrectomy. It was unsuccessful! |

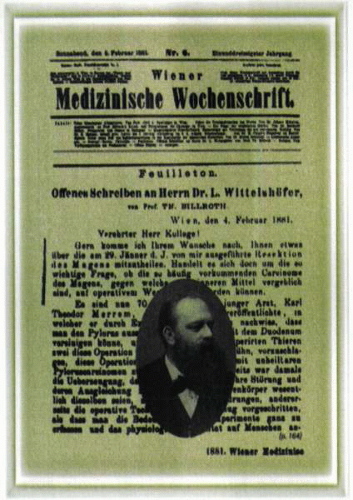

The issue of surgery of the stomach had been confounded for years by the problems related to sepsis and lack of adequate anesthesia. As late as the end of the nineteenth century, Naunyn felt obligated to describe it as “an autopsy in vivo.” Nevertheless, by 1881, Billroth, Péan, and Rydiger had resected the stomach, and Wölfler had successfully developed the procedure of gastroenterostomy. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Moynihan had transformed the treatment of peptic ulcer disease into a unique surgical discipline.

Unfortunately, the consequences of gastric and vagal surgery produced a generation of patients with either significant postvagotomy problems or postgastrectomy syndrome. The recognition in the first part of the century that the mucosal damage was caused by acid (“no acid—no ulcer”) and that this acid could be decreased by luminal neutralization resulted in a wave of enthusiasm for antacid preparations, bland diets, and milk infusion as therapeutic options. The subsequent identification of the histamine-2 receptor subtype and the development of agents specifically capable of blocking acid secretion by antagonism at this receptor revolutionized the management of the disease process and virtually obliterated surgery as a therapeutic option for peptic ulcer, except in cases of emergency.

The more recent identification of the molecular mechanism of acid secretion—the proton pump—resulted in the development of a new class of therapeutic agents, the PPIs.

By defining the pump as the therapeutic target, an almost complete inhibition of acid secretion, with consequent therapeutic efficacy hitherto undreamed of, can be achieved.

Although there is much debate about the initial observations of ulceration of the gastroduodenal mucosa, some of the best original descriptions originated in the work of Jean Cruveilhier (1791-1873). Born in Limoges, France, he subsequently studied with the great surgeon of Paris—Dupuytren—and, having attained the Chair of Pathology in Paris in 1836, subsequently became one of the foremost authorities on stomach ulcers in France. Cruveilhier’s interest in the subject of gastric ulcers was substantial, and his knowledge and experience in this area were widely recognized. In France at this time, the management of stomach ulcers became so closely linked with his contributions that the lesions were referred to as Cruveilhier’s disease. His comments thoughtfully addressed issues such as why an ulcer of the stomach might occur in a single place when the rest of the stomach was “in the state of perfect integrity.” Cruveilhier carefully

documented case histories and autopsies and defined in detail the pathology and sequelae of chronic gastric and duodenal ulceration.

documented case histories and autopsies and defined in detail the pathology and sequelae of chronic gastric and duodenal ulceration.

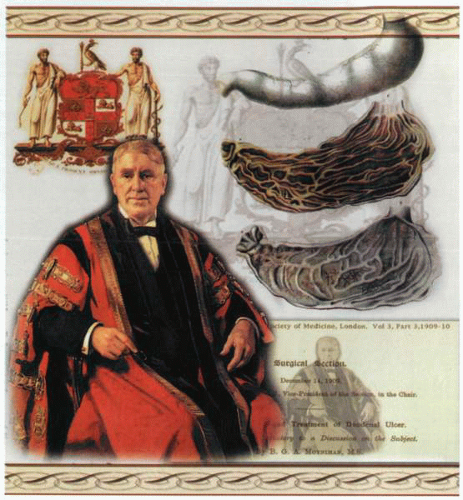

Similarly, contributions to the understanding of the management of peptic ulcer disease were provided by Berkeley Moynihan of Leeds, in England, and so powerful was his effect on prevailing thoughts in this area that British physicians referred to duodenal ulcer as Moynihan’s disease.

Cruveilhier’s great contributions lay mostly in the pathologic description of stomach ulcers. However, the therapy of his time was modest and revolved chiefly around the application of leeches, mustard plasters, bleeding, and various alcoholic concoctions, which presumably allayed anxiety and relieved pain. Moynihan, on the other hand, defined many of the early surgical therapeutic strategies for peptic ulcer and became widely known for his contributions to gastric surgery.

Despite his exaggerated enthusiasm for the surgical management of duodenal ulcer disease, Moynihan is noteworthy for his contribution to the scientific foundation of gastric surgery. As the President of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, he became the prime mover for the first introduction of science into surgical training programs.

The recognition of the association of ulceration of the duodenum with specific circumstances, such as burns, was first attributed to Curling in 1841, who called attention to the connection between cases of burn and acute ulceration

of the duodenum. Although it is likely that Dupuytren observed this relationship more than a decade before Curling, the former published little of his work, and his observations were not initially widely known.

of the duodenum. Although it is likely that Dupuytren observed this relationship more than a decade before Curling, the former published little of his work, and his observations were not initially widely known.

Confusion regarding the primacy of this observation was further clouded by the fact that Moynihan claimed that in 1834, James Long of Liverpool had first described duodenal ulcer in two patients with burns.

To date, the precise pathophysiology of the relationship between severe cutaneous burns and the development of peptic ulceration still remains unclear, although the association is important.

A further association of duodenal ulceration with surgery of the posterior cranial fossa was noted by Harvey Cushing and initially attributed to alteration in neural pathways regulating gastric physiology. Current investigation is still focused on the central nervous regulation of gastroduodenal physiology, but clear answers in this area are still lacking.

Further correlations between gastroduodenal ulceration and other related conditions noted the association of pancreatic tumors with peptic ulceration. The further elucidation of the neuroendocrine tumor source of gastrin and the consequences of acid hypersecretion led to the resolution of this relationship by Zollinger and Ellison. They identified the existence of a syndrome of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors associated with a peptic ulcer diathesis. Similar observations in conditions such as basophil leukemia and mastocytosis noted the excessive production of histamine with consequent acid hypersecretion and peptic ulcer disease in such patients.

Associations between the intake of salicylate-containing compounds and peptic ulceration were followed by similar observations in individuals using NSAIDs for the management of joint and muscle disease.

Nevertheless, despite the identification of a number of such associations with gastroduodenal ulceration, the etiology of the disease process was for the most part unrecognized until the identification of H. pylori and the elucidation of its relationship to peptic ulcer disease.

Gastric surgery

Until the mid-nineteenth century, the techniques of surgery were mostly confined to the extremities and usually related to the management of trauma. No surgeon would reasonably consider the violation of a body cavity before the introduction of anesthesia and antisepsis. Even under the latter conditions, both the morbidity and mortality were such that incursions into the peritoneal cavity were undertaken with considerable trepidation.

For the most part, the early reports of stomach surgery reflected the consequences of either military action with war wounds or incidental trauma. A therapeutic gastrostomy was reported in 1819 to remove a silver fork that had been “inadvertently” swallowed by a 26-year-old female servant. Jacques-Mathieu Delpech (1777-1832) of Montpellier confirmed the diagnosis of a

penetrating fork on noting a red inflamed mass on the anterior abdominal wall 5 months after the fork had been ingested. He was a shrewd enough clinician to persuade a colleague, Cayroche of Mende, to remove this foreign body (May 1, 1819) via an anterior abdominal incision. Delpech was subsequently assassinated by a former patient who felt that a varicocele operation had rendered him impotent.

penetrating fork on noting a red inflamed mass on the anterior abdominal wall 5 months after the fork had been ingested. He was a shrewd enough clinician to persuade a colleague, Cayroche of Mende, to remove this foreign body (May 1, 1819) via an anterior abdominal incision. Delpech was subsequently assassinated by a former patient who felt that a varicocele operation had rendered him impotent.