Hematology and Oncology

Paul A. Seligman

Acute Leukemia

What is the pathology of acute leukemia?

What are the primary classifications of acute leukemia, and why is this differentiation important?

What is the French, American, and British (FAB) classification of acute leukemia?

Are there any predisposing factors associated with acute leukemia?

What workup and other preparations should be done before initiating antileukemic therapy?

What are induction, consolidation, maintenance chemotherapy, and meningeal prophylactic therapy, and how do they differ in the treatment of acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) and acute nonlymphocytic leukemia (ANLL)?

What are the risks associated with antileukemic therapy, and what results can be expected?

Discussion

What is the pathology of acute leukemia?

Acute leukemia is the abnormal clonal expansion of blood cell precursors. The abnormality may occur at different stages of maturation of the cell, and this explains the different types of leukemia. Acute leukemia is usually a rapidly progressive disease, although there are occasional patients whose disease remains stable for weeks or even months. In general, however, it is not the leukemic cells per se that cause the morbidity and mortality in this disorder, but a lack of normal blood cells, resulting in anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia. This is brought about by the leukemic cells “crowding out” the normal cells in the bone marrow. Other data suggest that especially myeloid leukemia cells have an inhibitory effect on normal marrow cells. This lack of normal cells may therefore lead to life-threatening hemorrhage and infection.

What are the primary classifications of acute leukemia, and why is this differentiation important?

The primary classifications of acute leukemia are ALL and acute nonlymphocytic leukemia (ANLL, myeloid leukemia). The distinction is important because the therapy differs for each type (see answer to question 6). The overall ratio of ALL to ANLL is 1 : 6. ALL occurs most commonly in children, whereas ANLL more commonly affects adults.

What is the FAB classification of acute leukemia?

The FAB classification (Table 7-1) is based largely on the morphologic and histochemical characteristics displayed by the leukemic cells, as well as on the nature of the cell surface antigens and cytogenetic features. This information may lead to changes in patient management, either by directing the course of therapy or by defining the prognosis better. Table 7-1 also includes molecular changes that may affect therapy, but more often affect response to therapy.

Are there any predisposing factors associated with acute leukemia?

Certain genetic and environmental factors may predispose a person to acute leukemia. Many chromosomal alterations exist in the setting of the leukemias. The incidence of leukemia is increased in patients with congenital disorders associated with aneuploidy, such as Down syndrome, congenital

agranulocytosis, celiac disease, Fanconi syndrome, and von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis.

Table 7-1 The French, American and British (FAB) Classification of Acute Leukemia

Associated

FAB

Chromosome

classification

Description

Comment

Abnormalities

ALL

L1

Small blasts with little cytoplasm, little cell-to-cell variation

Most common morphology in childhood ALL

12 : 21

L2

Larger cells with greater amount of cytoplasm, greater cell-to-cell variation; irregular nuclei with multiple nucleoli

Most common morphology in adult ALL

—

L3

Large cells, strongly basophilic cytoplasm; often with vacuoles; nucleoli often multiple

Common in leukemia associated with Burkitt’s lymphoma

8 : 14 (i.e., Burkitt’s lymphoma)

ANLL

M1

Acute myelocytic leukemia: cells very undifferentiated with only occasional granules

—

—

M2b

Acute myelocytic leukemia: cells more differentiated with granules, and often with Auer rods

—

8:21a

M3

Acute promyelocytic leukemia: hypergranular promyelocytes

Often associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation, responds to differentiation agents

15:17a

M4b

Acute myelomonocytic leukemia: both monocytes and myelocytes predominate

Often occurs with extramedullary infiltration (gingival hypertrophy, leukemia cutis, and meningeal leukemia)

Inversiona 16

M5b

Acute monocytic leukemia: monoblasts with relatively agranular cytoplasm

Usually affects children or young adults

—

M6

Erythroleukemia: red blood cell precursors predominate, but myeloid blasts may also be seen

Also called Di Guglielmo’s syndrome

—

M7

Megakaryocytic leukemia: extremely variable morphology; may be diagnosed with monoclonal antibodies to platelets

Rare form of leukemia; very poor prognosis

—

aThese karyotypes are generally considered to be more likely to respond to chemotherapy.

bWhen M2, M4, and M5 leukemia occur after long-term myelodysplasia 11q 2; 3, monosomy 7 and other abnormal

karyotypes suggest decreased response to chemotherapy.

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; ANLL, acute nonlymphocytic leukemia.

Environmental factors implicated in the development of acute leukemia, particularly ANLL, include exposure to ionizing radiation and chemicals. Occupations and therapy that involve radiation exposure are known to increase the risk for acquiring acute leukemia. Chemicals, particularly the industrial use of benzene, and several therapeutic drugs (chloramphenicol, phenylbutazone, melphalan, chlorambucil, and others) are causal factors in acute leukemia. The findings from animal studies link certain viruses with acute leukemia; however, it is uncertain which viruses are actually an etiologic factor in human forms of leukemia, except for lymphomas caused by viruses that develop into a form of ALL.

What workup and other preparations should be done before initiating antileukemic therapy?

The pretreatment evaluation should include the patient’s medical and work history, especially the nature of any radiation or chemical exposure. A physical examination should include the patient’s temperature, plus examination of the optic fundi, lymph node areas, oropharynx and gingivae, perianal area, and cranial nerves. Laboratory studies should consist of a complete blood count with differential (the physician should examine the smear), as well as a blood chemistry profile that includes the measurements of uric acid and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Bone marrow aspirates and biopsy specimens should be obtained, and investigations should include cytogenetic studies. A transfusion workup should include human lymphocyte antigen (HLA) typing. Lumbar puncture should be performed in all patients suspected of having ALL or ANLL-M4, and the cerebrospinal fluid specimen should be subjected to the usual studies, plus cytologic analysis. A dental examination should be performed.

In addition, the patient’s condition should be stabilized before antileukemic therapy is initiated. Hemorrhage and infection should be brought under control. Greatly elevated myeloblast counts (e.g., >50,000/mm3) that occur in the setting of ANLL can lead to pulmonary complications as well as fatal intracerebral leukostasis and hemorrhage. Cranial irradiation, hydroxyurea, and leukapheresis have all been used to decrease the numbers of circulating leukemic cells rapidly, and hence reduce the risk of complications. (Because of the physical properties of the lymphocytic leukemic cell, this is rarely a problem in patients with ALL.)

Renal damage stemming from urate nephropathy may exist at the time of presentation or may occur with therapy, therefore urine alkalinization may prevent the need for dialysis. Patients should receive allopurinol (300 to 600 mg) for at least 24 hours before therapy to reduce the uric acid load, and this treatment should be continued until leukopenia and bone marrow hypocellularity have been achieved.

What are induction, consolidation, maintenance chemotherapy, and meningeal prophylactic therapy, and how do they differ in the treatment of ALL and ANLL?

These are the phases of therapy used for acute leukemia. Induction therapy is usually the initial therapy and is intended to accomplish complete remission (that is, no signs or symptoms of disease, normal blood counts, and no evidence of leukemia, i.e., <5% blasts in the bone marrow). This therapy is usually administered on an inpatient basis, and is very toxic. Consolidation therapy is given after complete remission is achieved. It is similarly toxic, and consists of either the same drugs as those used in induction therapy or different ones. Its object is to reduce the now clinically undetectable leukemic cell mass as much as possible. Maintenance therapy is usually given on an outpatient basis and is less toxic, although complications of therapy can and do arise. This phase usually lasts for 2 to 3 years. Meningeal prophylactic therapy is given by means of lumbar puncture or through a reservoir placed under the scalp that cannulates the third ventricle. Its goal is to reduce the recurrence rate of leukemia in the central nervous system (CNS), which is considered a sanctuary site.

All four therapy phases are used in ALL. In the treatment of ANLL, there is controversy over the use of maintenance therapy, although a second consolidation phase may be used. Meningeal prophylaxis is not used in the treatment of adult ANLL. However, CNS leukemia is more common in childhood ANLL, and prophylaxis is sometimes used in this setting. In general, the response to treatment and the prognosis are better in patients with ALL than in those with ANLL.

What are the risks associated with antileukemic therapy, and what results can be expected?

As already noted, acute leukemia is usually a rapidly progressive disease that is fatal without therapy. Because the therapy itself is toxic, the mortality rate during induction therapy for ANLL may reach as high as 20%. Some toxicities are specific to the drug used, and these are not discussed here. Nearly all therapies provoke nausea and vomiting, which can be controlled with medications. More significantly, antileukemic therapy is intended to deplete the bone marrow, with subsequent repopulation by normal cells. During this period of depletion, the patient becomes severely thrombocytopenic and must be supported by platelet transfusions (given prophylactically at various intervals to keep the platelet count above 10,000) and, usually, also by red blood cell transfusions.

Patients also become severely leukopenic, and this makes them very susceptible to infection. The typical signs and symptoms of infection (pus and purulent sputum) are often due to the actions of granulocytes, so infection is often subtle. The oral mucosa and perirectal areas are commonly overlooked sites of infection. Fever in a neutropenic patient must be considered infectious by origin, until proved otherwise. When this happens, examination and cultures should be carried out and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy started quickly. Antifungal agents are usually added if no improvement is seen after 4 to 7 days of fever. The patient must be monitored carefully and treated for herpes virus infection because disseminated infection can be rapidly fatal.

If the leukemic cell burden is great, antileukemic therapy may precipitate the tumor lysis syndrome, caused by the rapid release of cell degradation products. It is characterized by hyperuricemia (causing urate nephropathy), hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia. Advance recognition of patients at risk and subsequent treatment with vigorous hydration, allopurinol, and urine alkalinization 24 to 48 hours before the start of chemotherapy can usually prevent the syndrome. These patients must have their electrolyte, uric acid, phosphorus, calcium, and creatinine status repeatedly checked. Any metabolic abnormalities should be corrected and, if necessary, renal dialysis instituted early. Once the leukemic cell burden is decreased and degradation products cleared, the syndrome resolves.

Most children with ALL respond to therapy and achieve long-term survival. Although 90% of adults with ALL experience complete remission with initial therapy, the median remission duration ranges from 48 to 60 months, depending on the study. Median survival is 3 to 5 years. However, approximately one third of all patients achieve long-term disease-free survival. Late recurrences are rare.

Patients with ANLL face a worse prognosis. Approximately 75% experience complete remission, but most cases recur within 36 months. Of those who achieve complete remission, 20% to 25% show long-term disease-free survival. Bone marrow or stem cell transplantation with high-dose chemotherapy is often used, but is still under investigation as a therapy after the initial chemotherapy in ALL. The timing of transplantation (first remission, first relapse, or second remission), especially in ALL, is controversial. In ANLL, bone marrow transplantation (bone marrow rescue) with high-dose chemotherapy after a first remission has been associated with higher long-term survival rates. Older age (>40 years), use of unrelated donors, and evidence for residual disease at the time of transplantation reduce the efficacy of this treatment approach.

Case

A 63-year-old white man is seen in the emergency room with complaints of fever, fatigue, and malaise. He reports having intermittent epistaxis during the last week, mouth sores for the last 3 days, and a nonpruritic rash over his lower extremities, which was noted 24 hours before. He has experienced midchest pain for the last day, only on swallowing. He denies chemical, drug, or radiation exposure.

Physical examination reveals a temperature of 38.6°C (101.48°F). He has mild tachycardia, at 108 beats per minute. Head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat findings consist of a few petechiae over the soft palate. Multiple white plaques are seen on the oral mucosa, and there is hypertrophy of the gingivae. During examination of the skin, petechiae are found over the distal lower extremities. Other examination findings are normal. Specifically, no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly are found. Other sites of possible infection, including the chest and perirectal area, are clear. The chest radiographic study is likewise normal.

Laboratory findings are as follows: white blood cell count, 17,200/mm3 with 2% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 1% band forms, 16% lymphocytes, 4% monocytes, 5%

metamyelocytes, 4% basophils, and 68% blastocytes; hemoglobin, 11.1 g/dL; hematocrit, 32.6%; and platelets, 14,000/mm3. His electrolyte, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and aminotransferase levels are normal. His uric acid level is mildly increased at 9.2 mg/dL (normal, 3.5 to 8.0 mg/dL), as are his LDH level at 373 IU/L (normal, 30 to 220 IU/L). Examination of a peripheral blood smear reveals occasional nucleated red blood cells, few platelets, and many large cells containing finely reticulated nuclei, several nucleoli, cytoplasmic granules, and occasional Auer rods. Large cells with folded nuclei and large, prominent nucleoli are also seen.

metamyelocytes, 4% basophils, and 68% blastocytes; hemoglobin, 11.1 g/dL; hematocrit, 32.6%; and platelets, 14,000/mm3. His electrolyte, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and aminotransferase levels are normal. His uric acid level is mildly increased at 9.2 mg/dL (normal, 3.5 to 8.0 mg/dL), as are his LDH level at 373 IU/L (normal, 30 to 220 IU/L). Examination of a peripheral blood smear reveals occasional nucleated red blood cells, few platelets, and many large cells containing finely reticulated nuclei, several nucleoli, cytoplasmic granules, and occasional Auer rods. Large cells with folded nuclei and large, prominent nucleoli are also seen.

What is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

How is the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) calculated, and what is it in this patient?

Of what importance is the ANC?

Do the evaluation findings point to any specific infections?

What would you expect this patient’s bone marrow to show?

Should a lumbar puncture be performed in this patient?

Case Discussion

What is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

Considering the results of this patient’s complete blood count and peripheral blood smear, he has ANLL. The granular myelocytes and monocytes in the smear and the clinical evidence of extramedullary leukemic infiltration (gingival hypertrophy) point to a diagnosis of M4, or acute myelomonocytic leukemia. Examination of bone marrow specimens using special stains and chromosomal analysis can help confirm this diagnosis.

How is the ANC calculated, and what is it in this patient?

To calculate the ANC, multiply the total white blood cell count by the percentage of polymorphonuclear leukocytes plus the percentage of band forms. In this case, the patient has 17,200 white blood cells, with 2% polymorphonuclear leukocytes and 1% band forms, or: 17,200 (0.02 + 0.01) = 516 absolute neutrophils.

Of what importance is the ANC?

The ANC furnishes a rough estimate of the patient’s ability to fight infection. A patient with an ANC of less than 500 is considered neutropenic and very susceptible to overwhelming infection. This patient, with an ANC of approximately 500, fever, and a presumed diagnosis of acute leukemia, falls into this category. Careful examination, together with cultures of blood, sputum, oral lesions, and other possible sites of infection, should be done quickly, and the patient started on broad-spectrum antibiotics immediately. Any delay in the workup or institution of antibiotics may result in overwhelming and possibly fatal infection. Cultures are often negative in neutropenic patients, although clinically they appear to be septic and respond to antibiotics.

Do the evaluation findings point to any specific infections?

This patient complains of midchest pain on swallowing and physical examination reveals white oral plaques. A presumptive diagnosis of Candida esophagitis can be

made on the basis of these findings, and the patient should be started on antifungal agents as well as broad-spectrum antibacterial antibiotics. Neutropenic patients are susceptible to opportunistic infections, and candidiasis is very common in them.

What would you expect this patient’s bone marrow to show?

The bone marrow in this patient with ANLL would likely exhibit hypercellularity, with cellular elements often constituting 90% or more of the marrow. The numbers of red blood cell precursors and megakaryocytes will be decreased. The morphology may be normal, or there may be dyserythropoiesis (asynchronous maturing of the nuclear and cytoplasmic elements). The marrow will primarily show a monotonous pattern of cells similar to those seen in the peripheral smear. Flow cytometry should show cell surface markers indicative of immature myeloid cells with monocytoid characteristics. The chromosome analysis may show an abnormality such as monosomy 7 (especially if the patient had myelodysplasia), but will not show the abnormalities associated with, for example, M3 leukemia (Table 7-1). Recent studies suggest complex karyotypes in patients older than 60 years, that is, three or more aberrations have decreased response to therapy and based on comorbid factors these patients should be considered for investigational therapy or supportive care.

Should a lumbar puncture be performed in this patient?

This patient has a presumptive diagnosis of acute myelomonocytic leukemia. Lumbar punctures are routinely done in cases of ALL and ANLL-M4 because these leukemias are associated with meningitis. Nevertheless, any patient with acute leukemia and symptoms of meningitis or cranial nerve palsies should undergo a diagnostic lumbar puncture, regardless of the leukemic type.

However, the platelet count in this patient is only 14,000/mm3, and lumbar punctures should not be performed when the platelet count is less than 50,000/mm3 because of the risk of hemorrhage. Therefore, platelet transfusions must be given before attempting lumbar puncture to bring the count to 50,000/mm3 or more.

Suggested Readings

Baccarani M, Carbelli G, Amadori S, et al. Adolescent and adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: prognostic features and outcome of therapy— a study of 293 patients. Blood 1982;60:677.

Bennett JM, Young ML, Anderson JW, et al. Long-term survival in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 1997;8:2205.

Burnett A, Goldstone AH, Stevens RMF, et al. Randomized comparison of addition of autologous bone-marrow transplantation to intensive remission: results of MRC AML 10 trial. Lancet 1998;351:700.

Farag SS, Archer KJ, Mrozek K, et al. Pretreatment cytogenetics add to other prognostic factors predicting complete remission and long-term outcome in patients 60 years of age or older with acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 8461. Blood 2006;108:63.

Gale RP, Hoelzer D. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. New York: Wiley-Liss, 1990.

Koeffler HP. Syndromes of acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Ann Intern Med 1987;107:748.

Anemia

What is the definition of anemia, and what is the differential diagnosis based on the mean corpuscular volume (MCV)?

Why is it important to examine the peripheral blood smear, and what are the many diagnostic erythrocyte abnormalities and corresponding clinical conditions?

What is a reticulocyte, and how is the reticulocyte count used to characterize an anemia? What is the reticulocyte index, how is it calculated, and how is it used in the differential diagnosis of anemia?

What is the difference between α- and β-thalassemia, how are they distinguished clinically, and how is electrophoresis useful?

What is sickle cell anemia, and how is it manifested clinically? What is the sickle cell trait, and how is it manifested clinically?

Discussion

What is the definition of anemia, and what is the differential diagnosis based on the MCV?

Anemia is usually defined as an abnormally low hematocrit or hemoglobin concentration, and occurs when the rate of erythrocyte loss exceeds the rate of erythrocyte production. The differential diagnosis of anemia depends on whether the MCV is low, high, or normal. Table 7-2 lists the various possible diagnoses for each of these categories. Sometimes with mild anemia, a diagnosis may be entertained if the MCV is in the high or low range of normal.

Why is it important to examine the peripheral blood smear, and what are the many diagnostic erythrocyte abnormalities and corresponding clinical conditions?

Peripheral blood smear examination can reveal erythrocyte abnormalities that point to the correct diagnosis of the anemia. Echinocytes, or burr cells, for example are seen in uremia and pyruvate kinase deficiency. Elliptocytes are the abnormal erythrocytes seen in patients with hereditary elliptocytosis.

Nucleated red cells are found in the setting of stress or hematologic disease with bone marrow involvement. Schistocytes or fragments occur in patients with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. Sickle cells are found in the setting of sickle cell anemia. Spherocytes occur in immune-mediated hemolytic anemia and hereditary spherocytosis. Target cells form in the presence of liver disease and iron deficiency; they also occur after splenectomy.

Table 7-2 Differential Diagnosis of Anemia Based on Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV)

Low MCV

Normal MCV

High MCV

α-Thalassemia

Acute blood loss

Alcohol abuse

β-Thalassemia

Aplastic anemia

Aplastic anemia

Iron deficiency

Chronic disease

Cobalamin deficiency

Lead poisoning

Combination of macrocytic and

Folate deficiency

Sideroblastic anemia

microcytic causes

Hemolysis

Hemoglobinopathy

Hypothyroidism

Hemolysis

Liver disease

Iron deficiency

Myelodysplastic syndromes

What is a reticulocyte, and how is the reticulocyte count used to characterize an anemia? What is the reticulocyte index, how is it calculated, and how is it used in the differential diagnosis of anemia?

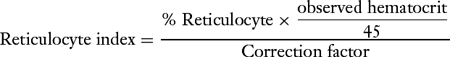

A reticulocyte is a young circulating red blood cell that exhibits basophilia under vital staining. The reticulocyte count is used to characterize the bone marrow’s attempt to compensate, if at all, for the anemia present. The reticulocyte index (Table 7-3) is a more useful means of characterizing anemia because it is determined by correcting the reticulocyte count for the hematocrit, assuming a normal hematocrit is 45%. This correction is necessary because reticulocytes are counted per 1,000 red blood cells.

An index of less than 2 is found in the setting of the hypoproliferative anemias. These consist of disorders of heme or globin synthesis, such as iron deficiency, anemia stemming from chronic disease, lead poisoning, sideroblastic anemias, and α, β, and other thalassemias; megaloblastic anemias resulting from cobalamin or folate deficiency; myelodysplastic syndromes; aplastic anemias; and other metabolic causes, such as renal insufficiency and hypothyroidism.

Hyperproliferative anemias are associated with a reticulocyte index greater than 2. These anemias arise as the result of acute blood loss; nutrient replacement, such as cobalamin, folate, or iron replacement, but before the resolution of anemia; both hereditary and acquired hemolysis; and primary or secondary polycythemia.

Automated reticulocyte counts introduced for general clinical practice are more accurate than “hand counts” and automatically calculate the reticulocyte index. These automated values also include the total number of reticulocytes, a measurement that might be helpful when obtaining serial values.

Table 7-3 The Reticulocyte Index

Hematocrit (%)

Correction Factor

45

1.0

35

1.5

25

2.0

Correction of the reticulocyte index for shift cells: shift cells-newly released erythrocytes.

Newer automated systems that will become available will give corrected reticulocyte count and a reticulocyte maturation index to account for “shift cells.”

What is the difference between α- and β-thalassemia, how are they distinguished clinically, and how is electrophoresis useful?

The α-thalassemias constitute abnormalities of the gene, or genes, responsible for the synthesis of the α chain of hemoglobin. Humans contain four genes for this purpose and each is responsible for approximately a fourth of the α chains synthesized. Any combination of from one to four of these α genes may be missing. Thalassemia is unapparent clinically when only one gene is missing, and this is called α1-thalassemia. This defect exists in up to 30% of the American black population. If two of the α genes are missing, the entity is referred to as α2-thalassemia. These patients are usually asymptomatic, although their hematocrit and MCV may be slightly low. This defect affects approximately 2% of African Americans. When three of the α genes are lacking, the patient exhibits the phenotype of α-thalassemia (Hemoglobin H disease) with a low hematocrit and MCV, and β-chain tetramers or hemoglobin H is found in the red blood cells. When all four α genes are missing, the result is usually a stillborn infant with hydrops fetalis.

α-Thalassemia is the most common form of thalassemia in the Southeast Asian population.

The β-thalassemias consist of abnormalities of the gene, or genes, responsible for the β chain of hemoglobin, and they cause insufficient β-chain synthesis. This leads to the formation of α-chain tetramers and inclusions of this hemoglobin attached to the plasma membranes of erythrocytes, resulting in hemolysis. Patients with heterozygous β-thalassemia exhibit a modest decrease in their hematocrit values and a marked decrease in their MCVs. Patients with homozygous β-thalassemia have severe anemia and low MCVs. They require transfusion, and complications may arise stemming from the excess accumulation of iron.

Electrophoresis may be used to suggest the diagnosis of α-thalassemia in patients missing three genes, and thereby having sufficient fast-migrating hemoglobin H (αl– and α2-thalassemia traits may not be detected). The precise number of missing α genes can be determined in hybridization studies through the use of a complementary DNA probe.

The findings yielded by hemoglobin electrophoresis are usually diagnostic in the setting of β-thalassemia. Because α-chain synthesis is normal in these patients, the other hemoglobins seen in adults, including hemoglobin A2 and F, are increased in a compensatory manner. Therefore, patients with heterozygous β-thalassemia would have elevated hemoglobin A2 and F levels with hemoglobin A present. Patients with homozygous β-thalassemia would have no hemoglobin A and markedly elevated hemoglobin F and A2 levels.

What is sickle cell anemia, and how is it manifested clinically? What is the sickle cell trait, and how is it manifested clinically?

Sickle cell disease is the most commonly recognized clinically significant hemoglobinopathy. It stems from a substitution of valine for glutamic acid in the β chain of hemoglobin and can be diagnosed by electrophoresis. Sickle cell anemia results when both β chains are abnormal. Sickled cells should be evident on

a peripheral blood smear. Hemoglobin S is less soluble than normal hemoglobin at a low oxygen tension, causing the hemoglobin molecules to crystallize, which deforms the red blood cells. These misshapen cells greatly increase the blood viscosity, which leads to small-vessel occlusion and hence pain and organ infarctions, specifically stroke as well as pulmonary, renal, and bone infarction.

Sickle cell disease may be manifested by a variety of crises: Pain is the most common symptom, and is thought to be secondary to red blood cell sludging and infarction. Splenic sequestration and dactylitis are common in children, but rare in adults. Aplastic anemia is uncommon, but is typically associated with infections, and is anticipated when reticulocyte counts decrease in the face of worsening of anemia. Megaloblastic anemia is usually secondary to folate deficiency, and arises because abnormal cells have a shortened life span. This increases the turnover of red blood cells and places an increased demand on folate stores. Sickle cell patients who enter with pain crisis or “chest syndrome” are at risk for multiorgan failure. When it becomes apparent that liver, kidney, and/or pulmonary function are declining, these patients should be considered for exchange transfusion.

The sickle cell trait is almost always asymptomatic because only one of the two β chains is abnormal. It can also be diagnosed by electrophoresis, and this is most important for the purposes of genetic counseling.

Case 1

A 42-year-old man is seen by his primary care physician because of a rectal urgency. On sigmoidoscopy, a mass is located at 8 cm. He undergoes resection to remove the mass and after surgery he receives adjuvant chemotherapy and undergoes pelvic radiation therapy. After he completes therapy, he returns to his primary care physician 6 months later with complaints of fatigue and dyspnea on exertion. As part of the evaluation, a complete blood count is obtained and reveals the following findings: white blood cell count, 3.9 × 109/L; hemoglobin, 8.2 g/dL; hematocrit, 24.4%; MCV, 86 fL; reticulocytes, 1%; and platelets, 450,000/mm3. The patient has a serum iron content of 23 μg/dL, a total iron-binding capacity of 256 μg/dL, and a ferritin level of 10 ng/mL.

What is the likely cause of this patient’s anemia, and how would you evaluate him further?

If the patient is iron deficient, why is his MCV 86 fL?

On the basis of the patient’s iron status, what treatment should be prescribed, and how should therapy be monitored?

Case Discussion

What is the likely cause of this patient’s anemia, and how would you evaluate him further?

The cause of this patient’s anemia is likely multifactorial. However, the ferritin level below 12 ng/mL and the percentage transferrin saturation (total iron-binding Fe/capacity) below 10% are both diagnostic for iron deficiency. He should receive oral iron supplementation, but he should be evaluated for a gastrointestinal source of

blood loss (e.g., recurrent tumor, second primary cancer, or some other nonmalignant source).

The patient may also be anemic and leukopenic due to the extensive exposure of the bone marrow to radiation during pelvic radiation therapy. This bone marrow damage may be compounded by the concomitant chemotherapy treatment.

Finally, the possibility of other contributory factors, such as folate and cobalamin deficiency, should also be investigated.

If the patient is iron deficient, why is his MCV 86 fL?

The MCV may be normal in the settings of early iron deficiency, although the red blood cell distribution width is high under these circumstances. The MCV may also be normal in iron-deficiency anemia complicated by another nutritional deficiency, such as folate or cobalamin deficiency. In this patient, the MCV is likely higher than expected as a result of his recent chemotherapy treatment that is associated with inhibition of DNA synthesis.

On the basis of the patient’s iron status, what treatment should be prescribed, and how should therapy be monitored?

The patient has iron deficiency. Ferrous sulfate (300 mg three times a day) provides 180 mg of elemental iron per day, which should normalize the hematocrit over the course of several months. The hematocrit should increase by 1% to 3% each week and his reticulocyte count should also increase significantly with this treatment.

The status of the absorption of oral iron can be easily demonstrated by determining the fasting serum iron level before and 3 to 4 hours after the ingestion of a single 300-mg tablet of ferrous sulfate. If normal, the level should rise by a minimum of two times the baseline (fasting) value. If the patient has decreased iron absorption, that is, due to “inflammation block” that decreases absorption, he should be treated with intravenous iron.

Case 2

A 67-year-old woman is seen for complaints of mild memory loss and fatigue. On evaluation, she is found to have an anemia, which is characterized by the following laboratory values: white blood cell count, 5,200/mm3; hemoglobin, 9.1 g/dL; hematocrit, 26.9%; MCV, 101 fL; reticulocytes, less than 1%; and platelets, 154/mm3. Her serum cobalamin level is 260 pg/mL and her folate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and liver function tests are normal. The patient does not abuse alcohol, and her peripheral blood smear is unrevealing.

How would you further evaluate this patient’s anemia?

On the basis of the laboratory results so far, what test, or tests, might be helpful in diagnosing the cause of this patient’s anemia?

Why might such a patient be deficient in cobalamin?

Case Discussion

How would you further evaluate this patient’s anemia?

Serum cobalamin and folate levels should be determined. In addition, a search for both ethanol abuse and liver disease should be undertaken and hypothyroidism

ruled out. If none of these is found to be a likely cause, other reasons for the anemia (refractory or aplastic anemia) should be explored. A peripheral blood smear should be examined for possible clues such as hypersegmented polymorphonuclear leukocytes (seen in cobalamin deficiency) or target cells (seen in liver disease).

On the basis of the laboratory results so far, what test, or tests, might be helpful in diagnosing the cause of this patient’s anemia?

This patient likely has cobalamin deficiency, although her serum cobalamin level of 260 pg/mL is within the normal range. Because studies have shown that such deficiency results in methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinemia, these metabolic substrates should be measured in this patient. Other testing that might be considered includes a Schilling test or measurement of anti–intrinsic factor-blocking antibodies.

Why might such a patient be deficient in cobalamin?

There are various causes of cobalamin deficiency. It can stem from the ingestion of insufficient animal protein, as seen in true vegetarians. Failure to release cobalamin from food binders or failure to secrete intrinsic factor results in pernicious anemia. Failure to absorb the intrinsic factor–cobalamin complex in the distal ileum, as occurs in patients who have undergone an ileal resection or who have regional enteritis, can also lead to cobalamin deficiency. Rare causes are abnormal or absent enzymes or transport proteins, and nitrous oxide abuse.

Suggested Readings

Akarsu S, Taskin E, Yilmaz E, et al. Treatment of iron deficiency anemia with intravenous iron preparations. Acta Haematol 2006;116:51.

Beutler E, Lichtman MA, Colter BS, et al., eds. Hematology, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

Wintrobe MM, ed. Clinical hematology, 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1998.

Bleeding Disorders

What are the major divisions of the coagulation system?

What are the general screening tests for evaluating each of the major divisions of the coagulation system?

What common disorders are associated with each of the major divisions of the coagulation system?

What are the clinical manifestations of various bleeding disorders?

What workup is indicated for a bleeding patient?

What therapies are available for the management of bleeding disorders?

Discussion

What are the major divisions of the coagulation system?

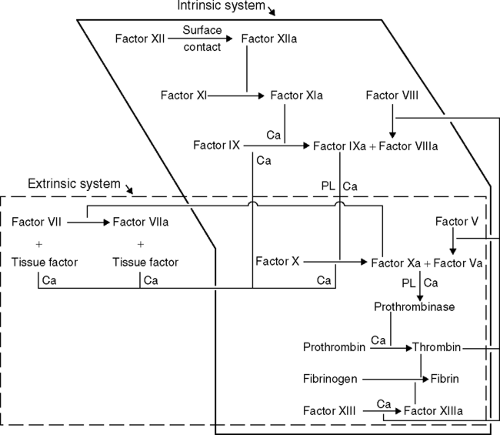

The coagulation system is quite complex, but can be viewed as consisting of at least three major components: the vascular endothelium, the blood

coagulation proteins (both those that promote clotting and those that lyse clots by means of the fibrinolytic system), and the platelets. The coagulation cascade represents a series of proteins that, when initiated, forms a fibrin clot. A simple outline of the cascade is shown in Table 7-4. Complex issues such as the exact mechanisms by which anticoagulants, such as protein C and protein S, function and how factor VII may activate factor IX are not completely understood.

What are the general screening tests for evaluating each of the major divisions of the coagulation system?

Vascular endothelial integrity can be assessed using the bleeding time. In this test, a nick is made in the skin under standardized conditions, and the time to cessation of bleeding is measured.

The blood coagulation proteins are usually evaluated by in vitro studies using the patient’s citrate-anticoagulated plasma. This is done by adding back various components of the coagulation cascade to the patient’s plasma to induce clot, and the procedure is standardized against plasma from an individual with normal plasma coagulation components. The two most common tests for doing

this are the prothrombin time (PT) and the partial tissue thromboplastin time (PTT). The PT measures the extrinsic pathway of the coagulation cascade, and this is done by adding tissue thromboplastin to the patient’s plasma. If there is a deficit in any of the common pathway components or factor VII, the clotting time is prolonged abnormally. The PTT measures the intrinsic and common pathways; a deficit in the common or intrinsic pathway proteins results in a prolonged PTT. A third, less commonly used, screening test is the thrombin time, which measures only the last step in the cascade— the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin— and is done by adding thrombin to the patient’s plasma. Therefore, if the patient has too little fibrinogen or a dysfunctional fibrinogen protein, the time is prolonged. Finally, each of the components of the cascade, including factors I to XIII, can be assayed directly to evaluate for deficits.

Platelets can be evaluated both quantitatively (by the platelet count) and functionally. Platelet function can be assessed by the bleeding time; qualitatively defective platelets do not form an adequate platelet plug and the bleeding time is prolonged. In addition, platelets can be analyzed in vitro for their aggregability using platelet stimulants (e.g., ristocetin).

What common disorders are associated with each of the major divisions of the coagulation system?

The vascular endothelium may be fragile in the setting of several acquired conditions, including vasculitis and long-term steroid use. This is important to realize because it may cause the bleeding time to be prolonged despite normal platelet number and function.

Deficits in the blood coagulation proteins may be congenital or acquired. The most common congenital disorders consist of deficiencies in factor VIII (hemophilia A) or factor IX (hemophilia B, or Christmas disease), which are inherited in an X-linked manner. Another common congenital disorder is von Willebrand’s disease, in which there is a deficit in von Willebrand’s factor. This factor is bound to factor VIII and is necessary for both platelet function and for clotting to take place by the intrinsic pathway.

Deficiencies in various factors can be acquired when their production is antagonized, as occurs with sodium warfarin (Coumadin; DuPont Pharma, Wilmington, DE) therapy, a substance that inhibits the production of activated vitamin K–dependent factors (factors II, VII, IX, X, and protein C and S). Another common situation that causes deficiencies in various factors is liver disease; because the liver is the site for the synthesis of nearly all the coagulation factors, severe liver disease results in deficient production of factors. Malnutrition, malabsorption, and liver disease can all lead to a deficit in vitamin K, with a subsequent deficit in the vitamin K–dependent factors. Finally, the overwhelming consumption of all factors can result in a coagulopathy, as occurs in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

The platelet population can be depressed because of either underproduction or excessive destruction. Underproduction occurs as a consequence of bone marrow suppression (brought about by chemotherapy, infections, drugs, or infiltration with other cells, such as occurs in the setting of leukemia or

cancer). Excessive destruction can occur in the setting of an enlarged spleen (sequestration), bleeding (consumption) or consumptive disorders (DIC or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome), and on an autoimmune basis [idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)].

Qualitative defects can be congenital, but are more often acquired and due to drug exposure (aspirin, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and some antibiotics) or uremia.

What are the clinical manifestations of various bleeding disorders?

Although any of the bleeding disorders may result in excessive hemorrhage associated with such events as surgical procedures, trauma, or gastrointestinal bleeding, each displays some characteristic features. Vascular fragility is typically associated with subcutaneous ecchymoses. Plasma coagulation protein deficiencies in patients with hemophilia are associated with spontaneous soft tissue and joint bleeds. Other plasma factor deficiencies, as well as platelet deficits, are associated with diffuse ecchymoses (cutaneous and soft tissue). Platelet deficits are also manifested by petechiae (small capillary hemorrhages in mucosal surfaces and areas of increased hydrostatic pressure, such as the ankles and feet) and purpura (larger areas of hemorrhage). Von Willebrand’s disease is unique in that it may present with both soft tissue bleeding (factor VII deficiency) and mucosal bleeding (platelet dysfunction).

What workup is indicated for a bleeding patient?

Evaluation of the bleeding patient begins with a good history taking. It needs to be determined if the condition is of long standing or is new. Questions about previous bleeding episodes (nosebleeds, bruising, menstrual flow, bleeding with trauma, surgery, and delivery) as well as family history are vital for determining the nature of the disorder. A careful drug history, including over-the-counter drug use, must be taken. The patient’s medical history and a review of symptoms may reveal evidence of autoimmune disorders or intercurrent illness.

Physical examination is important in evaluating the sites of bleeding (cutaneous, mucosal, soft tissue, or joint bleeding sites, as well as petechiae). An enlarged spleen and evidence of liver disease (e.g., spiders or hemangiomata) or malnutrition should be sought, and the patient’s overall medical condition should be assessed.

A screening for bleeding disorders should include a platelet count, PT, and PTT; if any of these results are abnormal or if there is evidence of mucosal bleeding, determination of a bleeding time may also be indicated.

If the PT or PTT is prolonged, the next step in the evaluation should be a 1:1 mix in which the patient’s plasma is mixed with normal plasma and the PT and PTT are determined again. If the patient is deficient in some factor, the normal plasma partially corrects this deficiency and the PT or PTT are corrected to a normal value. If an inhibitor to a particular factor is present, this inhibitor also blocks the action of the normal plasma, and the PT or PTT are not corrected. The most common inhibitor is the lupus anticoagulant, which is seen in the presence and absence of autoimmune disease; it is usually

associated with an elevated PTT that is not corrected with a 1:1 mix. It is associated with an increased risk of clotting, not bleeding.

If the platelet count is very low (20,000/mm3) and the PT and PTT are normal, a bone marrow biopsy may be indicated to determine whether there are adequate platelet precursors in the bone marrow. If platelet precursors are absent, an underproduction state exists; if precursors are present, this implies that the low platelet count stems from peripheral destruction. Using the detection of antiplatelet antibodies as evidence for the autoimmune destruction of platelets is not reliable because some normal people have antiplatelet antibodies without peripheral destruction, whereas the titers in people with ITP may be low.

What therapies are available for the management of bleeding disorders?

Blood components can be used to correct deficiencies in the divisions of the coagulation system. Fresh frozen plasma contains various percentages of each of the coagulation proteins and can be used when more than one factor is deficient (e.g., vitamin K–dependent factors). Cryoprecipitate contains von Willebrand’s factor, fibrinogen, and factor VIII, but is most commonly used in people with an acquired fibrinogen deficiency (e.g., DIC and liver disease). Because of the risk of viral infection (it is pooled from multiple donors), cryoprecipitate is no longer used as frequently for patients with mild hemophilia and von Willebrand’s disease. Instead, desmopressin (DDAVP) is now used in the treatment of these diseases, as well as in the platelet dysfunction associated with uremia and other qualitative defects. This drug works by stimulating the release of von Willebrand’s factor (factor VIII) from the endothelium. There are also specific heat-treated factor concentrates for factors VIII and IX, which can be used in the management of hemophilia.

Quantitative platelet problems caused by underproduction, as well as some consumptive states such as uncontrolled bleeding, can be treated with platelet transfusions. This is often futile in the setting of autoimmune destruction until the autoimmune process is arrested; in fact, platelet transfusion may accelerate destruction by stimulating the immune system. The usual initial treatment for ITP is with high-dose prednisone, followed by splenectomy if the prednisone fails to block the immune destruction. Transfusing platelets into a patient who has uremia or who is taking a drug that renders his or her own platelets dysfunctional is also futile because the transfused platelets quickly become affected as well.

Case 1

A 47-year-old white man comes to the emergency room complaining of hematemesis and a 4-day history of abdominal pain and passing black, tarry stools. He gives a history of peptic ulcer disease that is linked to heavy alcohol use, and this was associated with one previous episode of bleeding. He denies the use of any medications, including over-the-counter medicines, and denies a family history of bleeding. On review of the systems, he describes some increased bruising during the last 2 to 3 months. On physical examination he is found to be jaundiced and in moderate distress; alcohol is smelled on his breath. His skin is remarkable for scattered ecchymoses and spider angiomas. His liver

span is 15 cm and there is some tenderness plus a palpable spleen tip. The patient is continuing to pass melena and vomit bright red blood.

span is 15 cm and there is some tenderness plus a palpable spleen tip. The patient is continuing to pass melena and vomit bright red blood.

The following initial laboratory values are found: white blood cell count, 4,500/mm3 with a normal differential; hemoglobin, 6.0 g/dL; hematocrit, 18%; platelets, 87,000/mm3; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 95 mU/mL (normal, 0 to 35 mU/mL); alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 40 mU/mL (normal, 0 to 38 mU/mL); total bilirubin, 3.5 mg/dL (normal, <1.0 mg/dL); and alkaline phosphatase, 450 mU/mL (normal, 0 to 125 mU/mL).

How would you proceed with the evaluation of this patient’s bleeding problem?

What blood products, if any, would you give this patient?

What other medicines, if any, would you give this patient to manage his bleeding?

What factors may be contributing to this patient’s low platelet count?

Case Discussion

How would you proceed with the evaluation of this patient’s bleeding problem?

While emergency medical management of his bleeding is being provided through the placement of a nasogastric tube, together with the intravenous administration of fluids for blood pressure support as needed and typing and crossmatching in preparation for the administration of packed red blood cells, this patient with apparent chronic liver disease needs to have his coagulation status evaluated. Both the PT and PTT should be determined promptly and measurement of the fibrinogen level should be considered because it can be decreased in the setting of chronic liver failure. In this case, if the PT and PTT prove to be elevated, as expected, there is probably little reason for a 1:1 mix in this acutely ill patient because a deficiency state is very likely.

What blood products would you give this patient, if any?

If his PT or PTT proves to be elevated, the best blood product for replacing the deficient factors is fresh frozen plasma. In addition, if his fibrinogen level is measured and found to be less than 100 mg/dL, cryoprecipitate may also be indicated. Finally, it may become necessary to administer platelets if his count falls below 20,000/mm3 in the face of active bleeding.

What other medicines, if any, would you give this patient to manage his bleeding?

If history and physical examination findings are consistent with alcoholism and liver disease, vitamin K should also be given.

What factors may be contributing to this patient’s low platelet count?

His low platelet count may stem from multiple causes. First, the platelet count can fall in the face of massive bleeding (consumption). Second, he may be chronically underproducing platelets owing to either chronic alcohol suppression of the bone marrow or folic acid deficiency. Finally, he has an enlarged spleen, which may be sequestering his platelets.

Case 2

A 35-year-old Hispanic woman presents to the emergency room complaining of a nosebleed that has persisted for several hours. She denies a history of previous bleeding,

although she has noticed some increased bruising during the last week and the appearance of a small, purplish rash on her feet and ankles. She denies any excessive bleeding with the delivery of her three children and has not undergone any surgical procedures. She denies taking aspirin, although she has taken acetaminophen for relief of a mild backache, and is on no other medications. On review of her symptoms, she denies arthralgias, arthritis, fevers, cold symptoms, or other infectious symptoms; she has been in good health until now. On examination, she is found to be well developed and in no distress. There is some fresh as well as dried blood obscuring the nasal mucosa; she has no conjunctival hemorrhages but does have palatal petechiae. Her spleen is not palpable but there is a petechial rash around both ankles. Her nosebleed requires nasal packing for control.

although she has noticed some increased bruising during the last week and the appearance of a small, purplish rash on her feet and ankles. She denies any excessive bleeding with the delivery of her three children and has not undergone any surgical procedures. She denies taking aspirin, although she has taken acetaminophen for relief of a mild backache, and is on no other medications. On review of her symptoms, she denies arthralgias, arthritis, fevers, cold symptoms, or other infectious symptoms; she has been in good health until now. On examination, she is found to be well developed and in no distress. There is some fresh as well as dried blood obscuring the nasal mucosa; she has no conjunctival hemorrhages but does have palatal petechiae. Her spleen is not palpable but there is a petechial rash around both ankles. Her nosebleed requires nasal packing for control.

The following initial laboratory values are found: white blood cell count, 6,700/mm3 with a normal differential; hemoglobin, 14.2 g/dL; hematocrit, 42.2%; MCV, 85 μ3; platelets, 5,000/mm3; PT, 11.5 seconds (control, 12 seconds); and PTT, 28 seconds (control, 28.5 seconds).

What would you do next to evaluate this patient’s bleeding?

What results would you expect from the further evaluation of this patient’s bleeding?

What therapy would you institute in this patient?

Case Discussion

What would you do next to evaluate this patient’s bleeding?

With the normal coagulation findings and complete blood count, except for the platelet count, and the absence of other physical findings such as an enlarged spleen, a bone marrow biopsy is not essential to evaluate for megakaryocytes. Some clinicians may choose to treat for presumptive ITP and evaluate the patient in 24 hours.

What results would you expect from the further evaluation of this patient’s bleeding?

Her clinical picture is consistent with that of ITP, and, in this setting, an adequate bone marrow specimen would show an increased or normal number of megakaryocytes. If the physician chooses to treat the patient empirically for ITP (see the following text), the patient should have significant improvement (i.e., platelet count ≥20,000 with less incidence of bleeding) in 24 hours.

What therapy would you institute in this patient?

Platelet transfusions would not be helpful in this patient and might even accelerate the destructive process. Prednisone treatment (60 to 100 mg per day) should be initiated once bone marrow findings confirm the diagnosis or if the patient is treated empirically.

Case 3

You are asked to consult on the case of a 65-year-old white man with a history of severe rheumatoid arthritis, who has cervical spine instability that now requires orthopaedic stabilization. The preoperative laboratory results are as follows: white blood cell count, 10,000/mm3 with a normal differential; hemoglobin, 12 g/dL; hematocrit, 36%; MCV,

86 fL; platelets, 190,000/mm3; PT, 12 seconds (control, 11.5 seconds); PTT, 52.2 seconds (control, 32.5 seconds); and bleeding time, 10.5 minutes (normal, 0 to 9.5 minutes).

86 fL; platelets, 190,000/mm3; PT, 12 seconds (control, 11.5 seconds); PTT, 52.2 seconds (control, 32.5 seconds); and bleeding time, 10.5 minutes (normal, 0 to 9.5 minutes).

The patient denies any bleeding history, and had undergone a right knee replacement in the past without difficulty. He has taken large doses of aspirin in the past, but is currently on a nonsteroidal agent and takes no other medicines. There is no family history of bleeding disorders. On examination, he exhibits the sequelae of severe chronic rheumatoid arthritis, with deformed joints of the hands. He has no significant skin lesions. His spleen is not palpable and his liver is not enlarged.

What further preoperative evaluation would you do to reassure the surgeon that intraoperative hemostasis is adequate?

What blood products, if any, would you use in this patient?

What changes, if any, would you make in this patient’s medications?

Case Discussion

What further preoperative evaluation would you do to reassure the surgeon that intraoperative hemostasis is adequate?

The patient’s main coagulation abnormalities include a slightly prolonged bleeding time and an elevated PTT. His medications include a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agent, which can reversibly affect platelet function; this is the most likely source of his mildly increased bleeding time. In the absence of a bleeding history and if no emergency circumstances prevail, a 1:1 mix of his elevated PTT is indicated. His history of a chronic inflammatory condition is a strong indicator to have his lupus anticoagulant level determined.

What blood products, if any, would you use in this patient?

If a 1:1 mix does not correct in response to normal plasma, this indicates the presence of an inhibitor. His clinical picture is consistent with a lupus anticoagulant, which is actually associated with a risk of clotting, not bleeding, so no blood products are indicated. If his 1:1 mix does correct, implying a deficiency state, then specific assays of factor levels, including factors VIII and IX, may be necessary to identify the specific deficiency. This is highly unlikely in the absence of clinical bleeding.

This patient’s slightly prolonged bleeding time does not require any intervention.

What changes, if any, would you make in this patient’s medications?

His nonsteroidal medication should be stopped for at least 5 to 7 days before the spine stabilization procedure to allow normal platelet function to return. Immediately before surgery, his bleeding time should be checked again to confirm this return to normal.

Suggested Readings

Beutler E, Lichtman MA, Colter BS, et al., eds. Hematology, 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995.

Wintrobe MW. Clinical hematology, 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1993.

Breast Cancer

What is the incidence of breast cancer?

What is the natural history of breast cancer?

What are the risk factors for breast cancer?

Of what does the screening for breast cancer consist?

What is the TNM classification, and what are the stages of breast cancer?

What are the prognostic indicators associated with breast cancer?

What is the difference between modified radical mastectomy and lumpectomy plus radiation therapy in the treatment of stage I and II breast cancer, and what are the indications for each?

What is the role for adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of breast cancer?

Of what does the treatment of node-negative breast cancer consist?

What is the purpose and the underlying principles of endocrine manipulation in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer?

What is the role of systemic chemotherapy in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer?

Discussion

What is the incidence of breast cancer?

Breast cancer is the most common neoplasm in women, with an incidence that continues to rise and currently stands at 1 in 10 women. The incidence rises dramatically with age.

What is the natural history of breast cancer?

Breast cancer is considered to be a systemic disease from the time of diagnosis, regardless of the stage. The average doubling time varies from 23 to 500 days. Therefore, a 1-cm tumor may have existed for 2 to 17 years before diagnosis.

Despite local control, affected patients continue to die at a rate faster than that seen in age-matched control subjects for the first 30 years after treatment. In addition, patients dying from any cause are found to have evidence of tumor at autopsy. The most common sites of distant metastases are the bone, liver, and lung.

Paraneoplastic conditions that may be associated with breast cancer include hypercalcemia, neuromuscular disorders, dermatomyositis, acanthosis nigricans, and hemostatic abnormalities.

Common secondary malignancies in patients with breast cancer consist of cancer in the opposite breast, ovarian cancer, and colorectal carcinoma.

What are the risk factors for breast cancer?

High-risk factors (threefold or greater increase) for the development of breast cancer are:

Age greater than 50 years

Previous cancer in one breast, especially that occurring premenopausally

Breast cancer in the family, although the risk varies depending on whether the disease was in a first-degree family member, was unilateral or bilateral, and occurred premenopausally or postmenopausally: bilateral and premenopausal disease carries an 8.8 times greater risk; bilateral and postmenopausal disease carries a 5.4 times greater risk; unilateral and premenopausal disease carries a 3 times greater risk; and unilateral and postmenopausal disease carries a 1.5 times greater risk

Parity. Women who are nulliparous or who were first pregnant after 31 years of age have a three to four times increased risk

Ductal carcinoma in situ carries a 30% risk of becoming invasive

Certain forms of benign breast disease are associated with an increased risk of cancer Gross cystic disease with lesions exceeding 3 mm, multiple intraductal papillomas, and atypical ductal hyperplasia are considered premalignant

Intermediate-risk factors (1.2- to 1.5-fold increase) for the development of breast cancer consist of menstruation (either early menarche or late menopause); oral estrogen with progesterone therapy; alcohol consumption; diabetes mellitus; history of cancer of the uterus, ovary, or colon; and obesity.

Of what does the screening for breast cancer consist?

Women older than 20 years should perform breast self-examination every month. Premenopausal women should examine their breasts 5 to 7 days after the end of their menstrual cycle, and postmenopausal women should do this on the same day of every month.

Women should have their breasts examined by a physician every 2 to 3 years between the ages of 20 and 40 years and annually thereafter. The American Cancer Society and other agencies have recommended that a baseline mammogram should be obtained between the ages of 35 and 39 years, with mammograms obtained every 1 to 2 years in women aged 40 to 49 years and then yearly after the age of 50 years.

What is the TNM classification, and what are the stages of breast cancer?

The TNM (primary tumor, regional nodes, metastases) classification and the various stages of breast cancer are outlined in Table 7-5.

What are the prognostic indicators associated with breast cancer?

Table 7-6 summarizes the 5- and 10-year survival statistics associated with the various TNM stages. These statistics do not take into account results of adjuvant chemotherapy, but are useful in designing trials using adjuvant chemotherapy.

The patient’s hormonal status also has a bearing on her prognosis, in that estrogen- and progesterone receptor-positive tumors possess a 70% to 85% chance of responding to hormonal therapy; those women with only one-receptor positivity have exhibited a slightly lower response rate to hormone manipulation. Women with receptor-negative tumors do not respond to hormone manipulation.

Table 7-5 The TNM Classification of Breast Cancer

Disease Extent

Stage Groupinga

Primary Tumor (T)

Lymph Nodes (N)b

Distant Metastases (M)

TNM Classification

0

Noninvasive carcinoma in situ; Paget’s disease of the nipple (Tis)

Homolateral axillary nodes negative (N0)

None

Tis N0 M1

I

Greatest dimension ≤2 cm(T1)c

Homolateral axillary nodes negative (N0)

None

T1 N0 M0

II

Greatest dimension >2 cmand ≤5 cm (T2)c

Homolateral axillary nodes positive but not .xed (N1)

T1 N1 M0

T2 N0 or N1 M0

IIIA

Greatest dimension >5 cm(T3)c

Homolateral axillary nodes positive and .xed to one another, skin, or chest wall (N2)

None

T1 N2 M0

T2 N2 M0

T3 N0–2 M0

IIIB

Any size with (T4)c satellite skin nodules, skin ulceration, fixation to skin or chest wall, or edema of breast, including peau d’oranged

Supraclavicular or infraclavicular nodal involvement; edema of the arm with or without palpable axillary lymph nodes (N3)

None

T4 any N M0

Any T N3 M0

IV

Any size

Any status

Present

Any T any N M1

aThe American Joint Committee recognizes two stage groupings: postoperative-pathologic (presented in this table) and clinical-diagnostic.

bThe clinical-diagnostic stage grouping subdivides movable homolateral axillary lymph nodes into N1a—nodes not considered to contain tumor (approximately 33% are histologically positive); and N1b—nodes considered to contain tumor (approximately 25% are histologically negative).

cT0 indicates no tumor demonstrable in breasts; T1, T2, and T3 include tumor fixation to underlying pectoral fascia or muscle, which does not change the classification of lesions. (In flammatory breast cancer is classified as a separate entity and is not included in T4.)

dSkin dimpling and nipple retraction do not affect staging classification.

Adapted from the American Joint Committee for Cancer Staging and End-Results Reporting, 1983

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree