Hematologic Malignancies

Primary non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) of the lung are relatively rare, comprising fewer than 1% of primary pulmonary neoplasms and fewer than 10% of extranodal lymphomas. The most common entity is extranodal marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). Large B-cell lymphomas, including the distinctive entity lymphomatoid granulomatosis, make up most of the remaining primary NHLs. Hodgkin lymphoma and other subtypes of NHLs may rarely present as pulmonary primaries. On the other hand, the lungs are frequently involved by systemic lymphomas, leukemias, and plasma cell dyscrasias. Many of the features of these lesions are similar to those seen in the primary nodal or extranodal sites.

The malignant cells in MALT lymphomas usually show a range of morphologic features, and lymphomatoid granulomatosis, T-cell lymphomas, and Hodgkin lymphoma are all notable for their association with a polymorphous inflammatory background. Given these factors, primary diagnosis may be difficult on small biopsies, and open or thoracoscopic biopsy may be required.

Many cases may be diagnosed using immunoperoxidase studies on paraffin sections. B- and T-cell clonality may often be confirmed using polymerase reaction studies, also using paraffin-embedded material. If fresh material is available, flow cytometric analysis may confirm B-cell clonality or T-cell marker aberrancies in most cases. In situ hybridization is the most sensitive technique for detection of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. Cytogenetic studies are rarely required, although in situ hybridization for the t(11;18) or t(14;18) translocations seen in many MALT lymphomas may play a diagnostic role.

Part 1 Extranodal Marginal-Zone B-Cell Lymphoma

Jeffrey L. Jorgensen

Keith M. Kerr

MALT lymphoma is the most common primary lymphoma involving the lung. This is a low-grade B-cell lymphoma that occurs primarily in older individuals (average age about 60). Only about half of patients are symptomatic at presentation. This lymphoma usually presents as solitary or multiple nodules, or less commonly as patchy or diffuse infiltrates. Grossly, most cases show an ill-defined fleshy mass with preservation of the lung architecture. Hilar lymph nodes are involved in a minority of cases, and most cases do not show bone marrow involvement. Multiple extranodal sites are involved in a few cases. These lymphomas are generally indolent and may respond well to localized therapy. Large-cell transformation occurs in a minority of cases.

Differential diagnosis includes benign and borderline lymphoid proliferations such as nodular lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia, and other low-grade NHLs such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and mantle-cell lymphoma.

Histologic Features

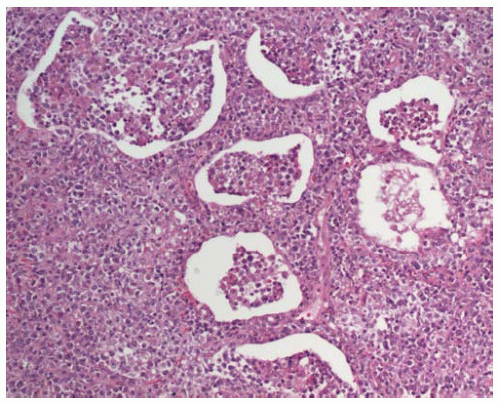

Dense lymphoid infiltrate with a lymphatic distribution along septa and bronchovascular bundles.

Pleural involvement or erosion of bronchial cartilage may be seen; if present, either of these features favor a malignant process.

Composed of varying proportions of small lymphocytes, intermediate-sized lymphocytes with moderately abundant pale cytoplasm (monocytoid, marginal-zone lymphocytes), plasma cells and plasmacytoid lymphocytes, and scattered large cells with vesicular chromatin and distinct nucleoli.

Dutcher bodies (nuclear pseudoinclusions) may be present in plasma cells or plasmacytoid lymphocytes; these are much more common in malignant lymphomas than in benign reactive conditions.

Lymphocytic infiltration of bronchial or bronchiolar epithelium, forming lymphoepithelial lesions, is seen in nearly all cases; however, this feature may also be seen in reactive conditions.

Most cases are associated with benign reactive germinal centers; some cases show “colonization” (infiltration) of germinal centers by lymphoma cells.

Plasma cells are most often reactive, with polyclonal staining for κ and λ light chains.

Some cases will show extensive plasmacytic differentiation, with monoclonal light-chain staining of plasma cells.

Many cases are associated with multinucleated giant cells and/or epithelioid granulomas.

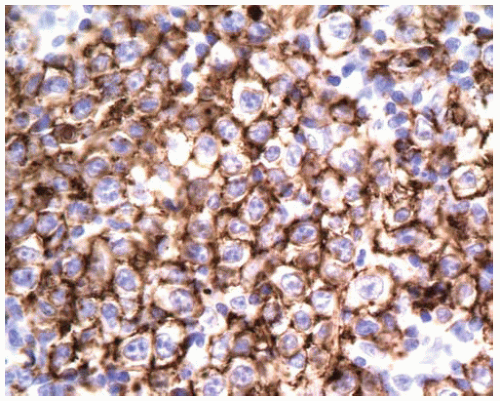

Immunopositive for B-cell markers (CD20; also CD22, CD79a, Pax-5).

Aberrant coexpression of CD43 on B-cells in some cases (note that T-cells, histiocytes, and plasma cells are usually positive for CD43).

Negative for CD5, CD10, BCL-6, and cyclin D1.

Staining of lung epithelium with pan-keratin may highlight lymphoepithelial lesions.

Diagnosis may hinge on demonstration of clonality by either flow cytometry of a fresh specimen (if necessary by repeat biopsy, possibly by fine-needle aspiration) or analysis of immunoglobulin heavy-chain genes by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Around half of cases carry a characteristic translocation involving the MALT1 locus on chromosome 18q21. These translocations can be identified by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or in the approximately one-third of cases with t(11;18), by reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

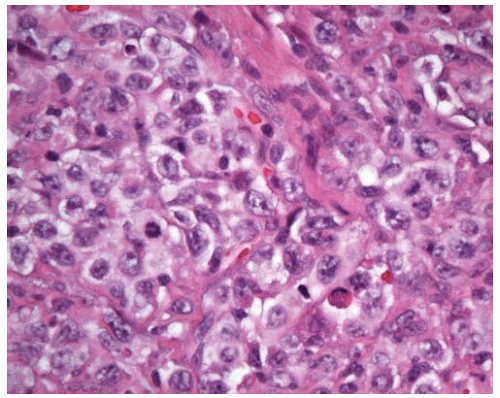

Figure 12.4 Scattered large cells are present in a background of small lymphocytes, some of which have increased pale cytoplasm (monocytoid lymphocytes). |

Part 2 Primary Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Jeffrey L. Jorgensen

Large B-cell lymphoma is the second most common primary NHL in the lung after MALT lymphoma. There is a wide age range, from children to adults. Patients are often symptomatic (dyspnea, chest pain, and/or hemoptysis). Differential diagnosis primarily includes poorly differentiated carcinoma. Other primary large-cell lymphomas of the lung are much less common; they include peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), Hodgkin lymphoma, and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma.

Histologic Features

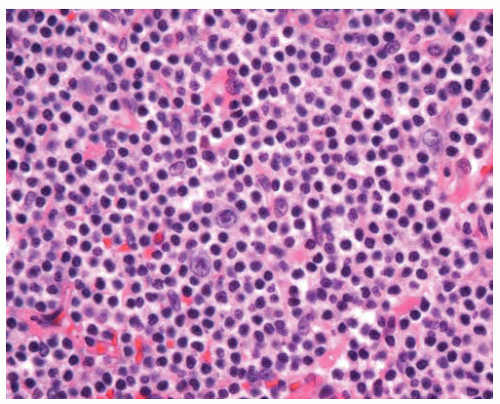

Sheets of discohesive large cells with oval to irregular nuclei, vesicular chromatin, and distinct nucleoli.

Pulmonary architecture is usually effaced, often with associated necrosis, with vascular invasion in some cases.

Tumor cells and fibrin may fill airspaces (“tumoral pneumonia”).

Diffuse areas or edges of a mass lesion often show infiltration in a lymphatic distribution.

Usually immunopositive for CD45 (LCA) and B-cell markers such as CD20.

Flow cytometric analysis may yield a false-negative result because of necrosis and/or cell fragility.

Part 3 Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis

Jeffrey L. Jorgensen

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LYG) is now regarded as a T-cell-rich, large B-cell lymphoma in which the malignant B-cells are positive for EBV. It usually presents in adults and is more common in males. Immunodeficiency is a risk factor (human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], congenital or iatrogenic), and LYG may occur in immunodeficient children. Most patients have pulmonary disease and often have respiratory symptoms. Other common sites of involvement are skin, central nervous system, kidney, and liver. Systemic symptoms are frequent. In the lung, LYG most often shows multiple, bilateral nodules, with possible cavitation in larger nodules. The disease is aggressive in the majority of patients, although occasional cases may be more indolent.

Differential diagnosis of low-grade lesions includes infectious and inflammatory conditions (Wegener granulomatosis, necrotizing sarcoid, bronchocentric granulomatosis). Granulomatous inflammation is actually uncommon in LYG, and the presence of granulomas or neutrophils favors an alternate diagnosis. Differential diagnosis of high-grade lesions includes carcinoma, melanoma, large-cell lymphoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Histologic Features

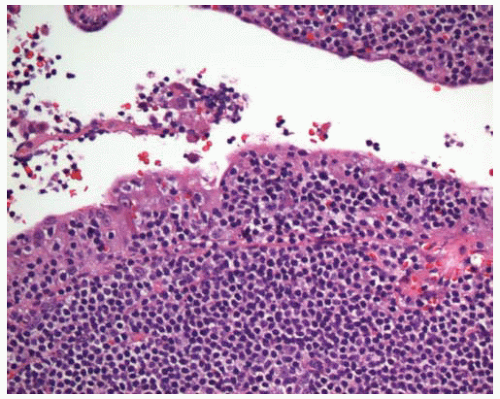

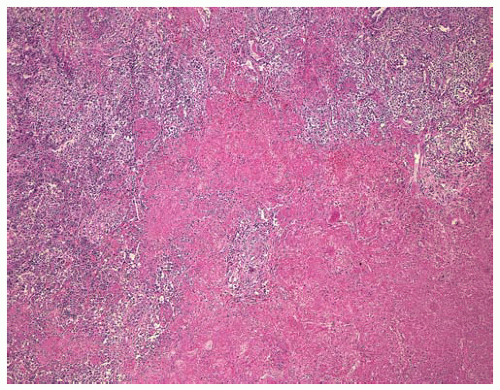

Polymorphous angiocentric lymphoid infiltrate.

Lymphocytic vasculitis often leads to vascular compromise and central necrosis.

Large atypical lymphocytes are usually in the minority and are occasionally pleomorphic or multinucleated.

Most cells are small- to intermediate-sized reactive lymphocytes that may show some nuclear irregularity.

Plasma cells and histiocytes may also be present, but granulomas, neutrophils, and eosinophils are not usually seen.

Diagnostic areas including large cells may be focal, and thorough sampling is warranted.

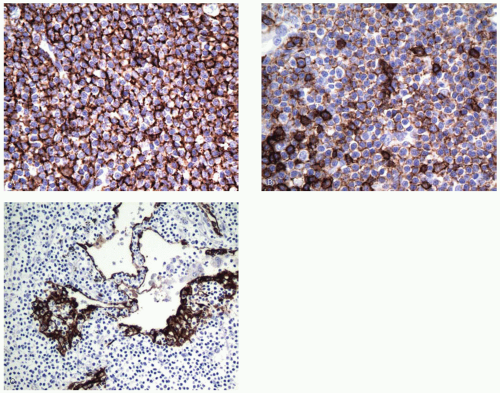

Large atypical cells are immunopositive for the B-cell marker CD20, and many of these are also immunopositive for EBV latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1).

Large cells are variably immunopositive for CD30 but negative for CD15.

Most small background lymphocytes are immunopositive for the T-cell marker CD3.

In situ hybridization studies on paraffin sections for EBV-expressed RNAs (EBER) may be a more sensitive detection technique for diagnosis and grading.

Grading is based on the number of EBV-positive B-cells: grade I with < 5 EBV-positive cells per high-power field and rare or absent large cells; grade II with 5 to 20 EBV-positive cells and scattered large cells; and grade III with numerous EBV-positive large cells.

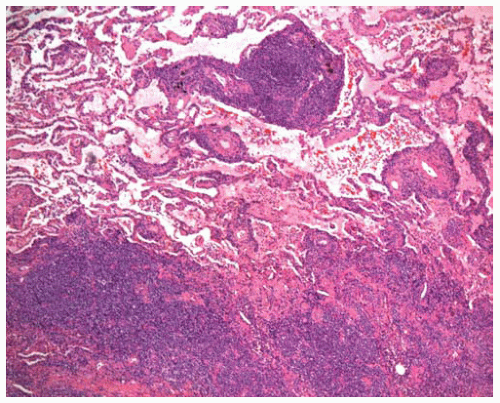

Figure 12.9 Large nodule containing a polymorphous lymphoid infiltrate, with central necrosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|