KEY POINTS

Gynecologic causes of acute abdomen include pelvic inflammatory disease, tubo-ovarian abcess, ovarian torsion, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, and septic abortion. Pregnancy must be ruled out early in assessment of reproductive-age patients presenting with abdominal or pelvic pain.

The general gynecology exam must incorporate the whole physical examination in order to adequately diagnosis and treat gynecologic disorders.

Benign gynecologic pathologies that are encountered at the time of surgery include endometriosis, endometriomas, fibroids, and ovarian cysts.

It is critical that abnormal lesions of the vulva, vagina, and cervix are biopsied for diagnosis before any treatment is planned; postmenopausal bleeding should always be investigated to rule out malignancy.

Early-stage cervical cancer is managed surgically, whereas chemoradiation is preferred for stage IB2 and above.

Pregnancy confers important changes to both the cardiovascular system and the coagulation cascade. Trauma in pregnancy must be managed with these changes in mind.

Pelvic floor dysfunction (pelvic organ prolapse, urinary and fecal incontinence) is common; 11% of women will undergo a reconstructive surgical procedure at some point in their lives.

Radical hysterectomy has unique risks of ureteral fistula and bowel dysfunction.

Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) should be considered in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations; RRSO and complete hysterectomy should be considered in women with Lynch syndrome.

Optimal debulking for epithelial ovarian cancer is a critical element in patient response and survival. The preferred primary therapy for optimally debulked advanced-stage ovarian epithelial ovarian cancer is intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND MECHANISMS OF DISEASE

The female reproductive tract is a unique component of the body with a multitude of tightly regulated functions. Many of the activities normally ongoing, such as angiogenesis and physiologic invasion, are necessary in order for the reproductive organs to fulfill their purpose and are usurped in disease. Immune surveillance is modified by multiple mechanisms under investigation and regulated in a different fashion, in order to allow implantation, placentation, and development of the fetus. How this potential disruption of normal immune barriers is involved in pathologic events is incompletely understood.

The pelvis is a very complex area, with a multitude of spatially and temporally varied functions. It is a site where pathologies ranging from mechanical events, such as ovarian torsion or ruptured ectopic pregnancy, to infection, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, to mass effects, including leiomyomata and malignancy, can present with similar and even overlapping symptoms and signs. An acute abdomen presentation in a woman of child-bearing potential can range from pregnancy-related catastrophes to appendicitis.

The ongoing rupture, healing, angiogenesis, and regrowth of the ovarian capsule and endometrium during the menstrual cycle uses the same series of biological and biochemical events that are also active in pathologic events such as endometriosis and endometriomas, mature teratomas, dysgerminomas, and progression to malignancy. Genetic abnormalities, both germline and somatic, that may cause competence and/or promote disease are now being uncovered, especially in the progression to malignancy, in pharmacogenomics, and in surgical risks such as bleeding and clotting. Incorporation of genetic and genomic information in disease diagnosis and assessment is a wave for the near future and may alter how we diagnose and follow disease, in whom we increase our diligence in searching for disease, and ultimately how we use the drug and other therapeutic armamentarium available to the treating physician.

These points will be incorporated with surgical approaches into discussions of anatomy, diagnostic workup, infection, surgical and medical aspects of the obstetric patient, pelvic floor dysfunction, and neoplasms.

ANATOMY

Clinical gynecologic anatomy centers on the pelvis (from Latin meaning basin). Aptly named, the bowl-shaped pelvis houses the confluence and intersection of multiple organ systems. Understanding those structural and functional relationships is essential for the surgeon and allows an appreciation for the interplay of sexual function and reproduction and a context for understanding gynecologic pathology.

The bony pelvis is comprised by the sacrum posteriorly and the ischium, ilium, and pubic bones anteromedially. It supports the upper body and transmits the stresses of weight bearing to the lower limbs in addition to providing anchors for the supporting tissues of the pelvic floor.1 The opening of the pelvis is spanned by the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm (Fig. 41-1). The muscles of the pelvic sidewall include the iliacus, the psoas, and the obturator internus muscle (Fig. 41-2). These muscles contract tonically and include, from anterior to posterior, bilaterally, the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, iliococcygeus, and coccygeus muscles. The first two of these muscles contribute fibers to the fibromuscular perineal body. The urogenital hiatus is bordered laterally by the pubococcygeus muscles and anteriorly by the symphysis pubis. It is through this muscular defect that the urethra and vagina pass, and it is the focal point for the study of disorders of pelvic support such as cystocele, rectocele, and uterine prolapse.

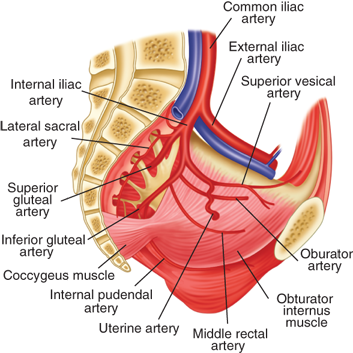

The rich blood supply to the pelvis arises largely from the internal iliac arteries except for the middle sacral artery originating at the aortic bifurcation and the ovarian arteries originating from the abdominal aorta. The internal iliac, or hypogastric, arteries divide into anterior and posterior branches. The latter supply lumbar and gluteal branches. From the anterior division of the hypogastric arteries arise the obturator, uterine, pudendal, middle rectal, inferior gluteal, and superior and middle vesical arteries (see Fig. 41-2).

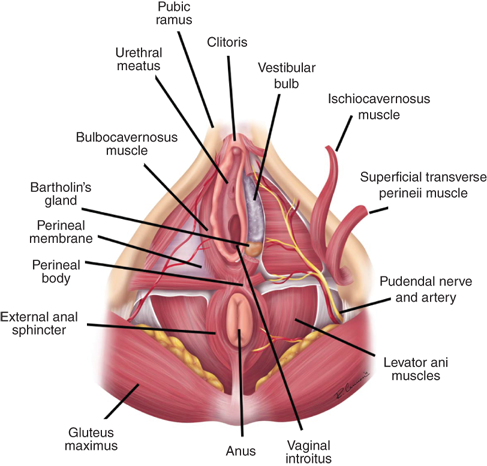

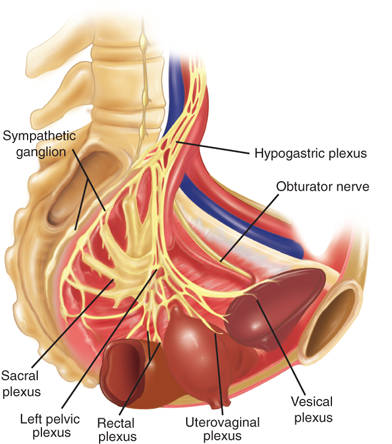

The major nerves found in the pelvis are the sciatic, obturator, and femoral nerves. Sympathetic fibers course along the major arteries, and parasympathetics form the superior and inferior pelvic plexus (Fig. 41-3). The pudendal nerve arises from S2-S4 and travels laterally, exiting the greater sciatic foramen, hooking around the ischial spine and sacrospinous ligament, and returning via the greater sciatic foramen. It travels through Alcock’s canal and becomes the sensory and motor nerve of the perineum (see Figs. 41-1 and 41-3). The motor neurons serve the tonically contracting urethral and anal sphincter, and direct branches from the S2-S4 nerves serve the levator ani muscles. During childbirth and other excessive straining, this tethered nerve (along with the levator ani muscles) is subject to stretch injury and at least partially responsible for many female pelvic floor disorders.

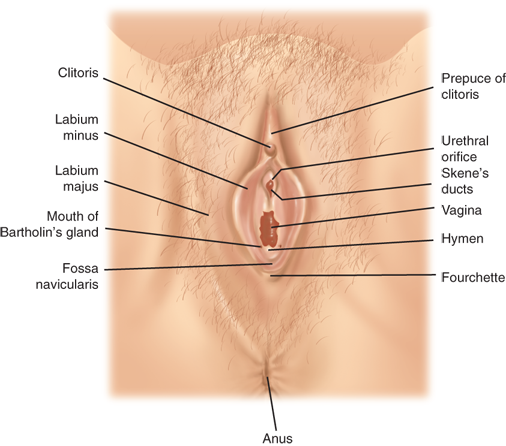

The labia majora form the cutaneous boundaries of the lateral vulva and represent the female homologue of the male scrotum (Fig. 41-4). The labia majora are fatty folds covered by hair-bearing skin in the adult. They fuse anteriorly over the anterior prominence of the symphysis pubis, the mons pubis. The deeper portions of the adipose layers are called Colles’ fascia and insert onto the inferior margin of the perineal membrane, limiting spread of superficial hematomas inferiorly. Adjacent and medial to the labia majora are the labia minora, smaller folds of connective tissue covered laterally by non–hair-bearing skin and medially by vaginal mucosa. The anterior fusion of the labia minora forms the prepuce and frenulum of the clitoris; posteriorly, the labia minora fuse to create the fossa navicularis and posterior fourchette. The term vestibule refers to the area medial to the labia minora bounded by the fossa navicularis and the clitoris. Both the urethra and the vagina open into the vestibule. Skene’s glands lie lateral and inferior to the urethral meatus. Cysts, abscesses, and neoplasms may arise in these glands.

Erectile tissues and associated muscles are in the space between the perineal membrane and the vulvar subcutaneous tissues (see Fig. 41-1). The clitoris is formed by two crura and is suspended from the pubis. Overlying the crura are ischiocavernosus muscles, which run along the inferior surfaces of the ischiopubic rami. Extending medially from the inferior end of the ischiocavernosus muscles are the superficial transverse perinei muscles. These terminate in the midline in the perineal body, caudal and deep to the posterior fourchette. Vestibular bulbs lie just deep to the vestibule and are covered laterally by bulbocavernosus muscles. These originate from the perineal body and insert into the body of the clitoris. At the inferior end of the vestibular bulbs are Bartholin’s glands, which connect to the vestibular skin by ducts.

The vagina is an elastic fibromuscular tube opening from the vestibule running superiorly and posteriorly, passing through the perineal membrane. The lower third is invested by the superficial and deep perineal muscles; it incorporates the urethra in its anterior wall and has a rich blood supply from the vaginal branches of the external and internal pudendal arteries. The upper two thirds of the vagina are not are not invested by muscles. This portion lies in opposition to the bladder base anteriorly and the rectum and posterior pelvic cul-de-sac superiorly. The cervix opens into the posterior vaginal wall bulging into the vaginal lumen.

Figure 41-5 is a view of the internal genitalia as one would approach the pelvis from a midline abdominal incision. The central uterus and uterine cervix are supported by the pelvic floor muscles. They are suspended by the lateral fibrous cardinal, or Mackenrodt’s ligament, and the uterosacral ligaments, which insert into the paracervical fascia medially and into the muscular sidewalls of the pelvis laterally. Posteriorly, the uterosacral ligaments provide support for the vagina and cervix as they course from the sacrum lateral to the rectum and insert into the paracervical fascia. Emanating from the uterine cornu and traveling through the inguinal canal are the round ligaments, eventually attaching to the subcutaneous tissue of the mons pubis. The peritoneum enfolding the adnexa (tube, round ligament, and ovary) is referred to as the broad ligament, which separates the pelvic cavity into an anterior and posterior component.

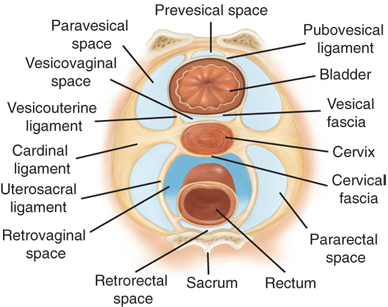

The peritoneal recesses in the pelvis anterior and posterior to the uterus are referred to as the anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs. The latter is also called the pouch or cul-de-sac of Douglas. On transverse section, several avascular, and therefore important, surgical planes can be identified (Fig. 41-6). These include the lateral paravesical and pararectal spaces and, from anterior to posterior, the retropubic or prevesical space of Retzius and the vesicovaginal, rectovaginal, and retrorectal or presacral spaces.

These avascular tissue planes are often preserved and provide safe surgical access when the intraperitoneal pelvic anatomy is distorted by tumor, endometriosis, adhesions, or infection. As an example, the ureter is at significant risk of iatrogenic injury in the context of such pathology. Using the avascular retroperitoneal planes, the ureter can be traced into the pelvis as it crosses the distal common iliac arteries laterally into the pararectal space and then courses inferior to the ovarian arteries and veins until crossing under the uterine arteries into the paravesical space just lateral to the cervix. After traveling to the cervix, the ureters course downward and medially over the anterior surface of the vagina before entering the base of the bladder in the vesicovaginal space.

The typically pear-shaped uterus consists of a fundus, cornua, body, and cervix. It lies between the bladder anteriorly and the rectosigmoid posteriorly. The endometrium lines the cavity and has a superficial functional layer that is shed with menstruation and a basal layer from which the new functional layer is formed. Sustained estrogenic stimulation can lead to hyperplastic changes or carcinoma. Adenomyosis is a condition in which benign endometrial glands infiltrate into the muscle or myometrium of the uterus. The myometrium is composed of smooth muscle, and the contraction of myometrium is a factor in menstrual pain and is essential in childbirth. The myometrium can develop benign smooth muscle neoplasms known as leiomyoma or fibroids.

The cervix connects the uterus and vagina and projects into the upper vagina. The vagina forms an arched ring around the cervix described as the vaginal fornices—lateral, anterior, and posterior. The cervix is about 2.5 cm long with a fusiform endocervical canal lined by columnar epithelium lying between an internal and external os, or opening. The vaginal surface of the cervix is covered with stratified squamous epithelium, similar to that lining the vagina. The squamocolumnar junction, also referred to as the transformation zone, migrates at different stages of life and is influenced by estrogenic stimulation. The transformation zone develops as the columnar epithelium is replaced by squamous metaplasia. This transformation zone is vulnerable to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and resultant dysplastic changes. These changes can be detected by microscopic assessment of a cervical cytologic (or Pap) smear. If the duct of a cervical gland becomes occluded, the gland distends to form a retention cyst or Nabothian follicle.

The bilateral fallopian tubes arise from the upper lateral cornua of the uterus and course posterolaterally within the upper border of the broad ligament. The tubes can be divided into four parts. The interstitial part forms a passage through the myometrium. The isthmus is the narrow portion extending out about 3 cm from the myometrium. The ampulla is thin-walled and tortuous with its lateral end free of the broad ligament. The infundibulum is the distal end fringed by a ring of delicate fronds or fimbriae. The fallopian tubes receive the ovum after ovulation. Peristalsis carries the ovum to the ampulla where fertilization occurs. The zygote transits the tube over the course of 3 to 4 days to the uterus. Abnormal implantation in the fallopian tube is the most common site of ectopic pregnancies. The tubes may also be infected by ascending organisms, resulting in tubo-ovarian abscesses.

The ovaries are attached to the uterine cornu by the proper ovarian ligaments, or the utero-ovarian ligaments. The ovaries are suspended from the lateral pelvis by their vascular pedicles, the infundibulopelvic (IP) ligaments or ovarian arteries. The IP ligaments are paired branches from the abdominal aorta arising just below the renal arteries. They merge with the peritoneum over the psoas major muscle and pass over the pelvic brim and the external iliac vessels. The ovarian veins ascend at first with the ovarian arteries, and then track more laterally. The right ovarian vein ascends to drain directly into the inferior vena cava, whereas the left vein drains into the left renal vein. Lymphatic drainage follows the arteries to the para-aortic lymph nodes. The ovaries are covered by a single layer of cells that is continuous with the mesothelium of the peritoneum. Beneath this is a fibrous stroma within which are embedded germ cells. At ovulation, an ovarian follicle ruptures through the ovarian epithelium.

EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

A complete history is a seminal part of any assessment (Table 41-1). Many gynecologic diseases can present with broad constitutional symptoms, occur secondary to other conditions, or be related to medications. A full history should include particular attention to family history; organ system history, including breast, gastrointestinal, and urinary tract symptoms; and a careful medication, anesthesia, and surgical history. The key elements of a focused gynecologic history include the following:

| ISSUE | ELEMENTS TO EXPLORE | ASSOCIATED ISSUES |

|---|---|---|

| Menstrual history | Age at menarche, menopause. Bleeding pattern, postmenopausal bleeding, spotting between periods Any medications (warfarin, heparin, aspirin, herbals, others) or personal or family history that might lead to prolonged bleeding times | Identifies abnormal patterns related to endocrine, structural, infectious, and oncologic etiologies |

| Obstetrical history | Number of pregnancies, dates, type of deliveries, pregnancy loss, abortion, complications | Identifies potential surgical complications due to previous cesarean sections |

| Infectious diseases | Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and treatment and/or testing for these | Also need to explore history of other gastrointestinal diseases that may mimic STD (Crohn’s, diverticulitis) |

| Contraceptive history | Present contraception if appropriate, prior use, type and duration | Concurrent pregnancy with procedure or complications of contraceptives |

| Cytologic screening | Frequency, results (normal, prior abnormal Pap), any prior surgery or diagnoses, human papillomavirus testing history | Prolonged intervals increase risk of cervicalcancer Relationship to anal, vaginal, vulvar cancers |

| Prior gynecologic surgery | Type (laparoscopy, vaginal, abdominal); diagnosis (endometriosis?, ovarian cysts?, tubo-ovarian abscess?); actual pathology if possible | Assess present history against this background (for example, granulosa cell pathology; is it now recurrent?) |

| Pain history | Site, location, relationship (with urination, with menses, with intercourse at initiation or deep penetration, with bowel movements), referral | Assesses relationship to other organ systems and potential involvement of these with process Common examples presenting as pelvic pain, ureteral stone, endometriosis with bowel involvement, etc. |

Date of last menstrual period, if premenopausal

History of contraceptive and postmenopausal hormone use

Obstetrical history

Age at menarche and menopause (method of menopause, e.g., drug, surgical)

Menstrual bleeding pattern

History of pelvic assessments, including cervical smear results

History of pelvic infections, including HPV, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status

Sexual history (number of lifetime partners)

Prior gynecologic surgery(s)

For many women, their gynecologist is their primary care physician. When that is the case, it is necessary that a full medical and surgical history be taken and that, in addition to the pelvic examination, the minimum additional examination should include assessment of the thyroid, breasts, and cardiopulmonary system. The pelvic examination starts with a full abdominal examination. Inguinal node evaluation is performed before placing the patient’s legs in the dorsal lithotomy position (in stirrups). A flexible, focused light source is essential, and vaginal instruments including speculums of variable sizes and shapes including pediatric sizes (Graves and Pederson) are required to assure that the patient’s anatomy can be fully and comfortably viewed.

The external genitalia are inspected, noting the distribution of pubic hair, the skin color and contour, the Bartholin and Skene’s glands, and perianal area. Abnormalities are documented, and a map with measurements of abnormalities is drawn. A warmed lubricated speculum is inserted into the vagina and gently opened to identify the cervix if present, or the vaginal apex if not. If there is a concern that a malignancy is present, careful digital assessment of a vaginal mass and location may be addressed prior to speculum placement in order to avoid abrading a vascular lesion and inducing hemorrhage. The speculum would then be inserted just short of the length to the mass in order to view that area directly before advancing. An uncomplicated speculum exam includes examination of the vaginal sidewalls; assessment of secretions, including culture if necessary; and collection of the cervical cytologic specimen if indicated (see later section, Common Screening and Testing).

A bimanual examination is performed by placing two fingers in the vaginal canal; one finger may be used if patient has significant vaginal atrophy or has had prior radiation with stenosis (Fig. 41-7). Carefully and sequentially assess the size and shape of the uterus by moving it against the abdominal hand, and assess the adnexa by carefully sweeping the abdominal hand down the side of the uterus. The rectovaginal examination, consisting of one finger in the vagina and one in the rectal vault, is used to further examine and characterize the location, shape, fixation, size, and complexity of the uterus, adnexa, cervix, and anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs. The rectovaginal exam also allows examination of the uterosacral ligaments from the back of the uterus sweeping laterally to the rectal finger and the sacrum, and a stool sample for occult blood can be obtained during this exam.

It is critical that presurgical assessments include a full general examination. This is particularly important with potential oncologic diagnoses or infectious issues, in order to assure that the proposed surgery is both safe and appropriate. Complications such as sites of metastatic cancer or infection, associated bleeding and/or clotting issues and history, and drug exposure, allergies, and current medications must be addressed.

The most recent cervical cytology guidelines by the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force has increased the intervals for most women given the known natural history of HPV-related cervical dysplasia progression to cancer.2 The very high negative predictive value of the HPV test allows for this change. The current recommendations call for cervical smear screening every 3 years in women age 21 to 65 years. If an HPV test performed at the same time also is negative, a Pap and HPV test combination does not need to be repeated in women age 30 to 65 for 5 years. HPV testing should not be performed as a screening test in women under age 30 due to the high prevalence of HPV, as well as the high likelihood of resolution of infection. Women with a history of cervical dysplasia or cancer need more frequent screening based on their diagnosis.

During a speculum exam, a cotton-tipped applicator is used to collect the vaginal discharge; it is smeared on a slide with several drops of 0.9% normal saline to create a saline wet mount. A cover slide is placed and the slide is evaluated microscopically for the presence of mobile trichomonads (Trichomonas vaginalis) or clue cells (epithelial cells studded with bacteria, seen in bacterial vaginosis; Table 41-2). A potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet mount is the slide application of the collected vaginal discharge with 10% KOH; this destroys cellular elements. The test is positive for vaginal candidiasis when pseudohyphae are seen (Table 41-2).

| BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS | VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS | TRICHOMONIASIS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen | Anaerobic organisms | Candida albicans | Trichomonas vaginalis |

| % of vaginitis | 40 | 30 | 20 |

| pH | >4.5 | <4.5 | >4.5 |

| Signs and symptoms | Malodorous, adherent discharge | White discharge, vulvar erythema, pruritus, dyspareunia | Malodorous purulent discharge, vulvovaginal erythema, dyspareunia |

| Wet mount | Clue cells | Pseudohyphae or budding yeasts in 40% of cases | Motile trichomonads |

| KOH mount | Pseudohyphae or budding yeasts in 70% of cases | ||

| Amine test | + | − | − |

| Treatment | Metronidazole 500 mg bid × 7 d or 2 g single dose, metronidazole or clindamycin vaginal cream | Oral fluconazole 150 mg single dose, vaginal antifungal preparations | Metronidazole 2 g single dose and treatment of partner |

Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) has emerged as the diagnostic test of choice for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. A vaginal swab, endocervical swab, and/or urine sample can be used for this test. The test can be completed within hours and has been found to be more sensitive than cultures.

Qualitative urinary pregnancy tests for β-hCG are standard prior to any surgery in a woman of reproductive age and potential, regardless of contraception history. In addition, serum quantitative β-hCG testing is appropriate for evaluation of suspected ectopic pregnancy, gestational trophoblastic disease, or ovarian mass in a young woman. In the case of ectopic pregnancy, serial levels are required when a pregnancy cannot be identified in the uterine cavity. As a general rule, 85% of viable intrauterine pregnancies will have at least a 66% rise in the β-hCG level over 48 hours.

Any abnormal vulvar or vaginal lesion including skin color changes, raised lesions, or ulcerations should be biopsied. Local infiltration with local anesthetic is followed by a 3- to 5-mm punch biopsy appropriate to the lesion. The specimen is elevated with Adson forceps and cut from its base with scissors. The vaginal biopsy can sometimes be difficult to perform because of the angle of the lesion. After injection with local anesthetic, traction of the area with Allis forceps and direct resection of the lesion with scissors or cervical biopsy instrument (Schubert, Kevorkian, etc.) can achieve an adequate biopsy.

In cases of an abnormal Pap smear cytology, a colposcopy is performed for a histologic evaluation. A colposcope is used to achieve 2× to 15× magnification of the cervix. Once the cervix is visualized, cervical mucus, if present, is removed, and then 3% acetic acid is applied to the cervix for 1 minute. This application dehydrates cells and causes dysplastic cells with dense nuclei to appear white. The entire squamocolumnar junction is visualized during an adequate colposcopy. This area is seen as the transition from the smooth-appearing squamous ectocervix to the pink endocervical tissue. Acetowhite areas or areas with punctation, mosaicism, or atypical blood vessels seen during colposcopy may represent dysplasia or cancer and should be biopsied.

Endometrial sampling should be performed before planned hysterectomy if there is a history of bleeding between periods, heavy and/or frequent menstrual periods, or postmenopausal bleeding. A patient with the potential for pregnancy should have a pregnancy test before the procedure. An endometrial pipelle is inserted after cervical cleaning, and the depth of the uterine cavity is noted. The endometrial specimen is obtained by pulling on the plunger within the pipelle, creating a small amount of suction. The pipelle is rotated and pulled back from the fundus to the lower uterine segment within the cavity to access all sides.3 Additional passes may be needed in order to acquire an adequate amount of tissue.

When a patient presents with copious vaginal discharge, the provider must be concerned about a fistula with the urinary or gastrointestinal tract. A simple office procedure can be performed when there is a concern for a vesicovaginal fistula. A vaginal tampon is placed, followed by instillation of sterile blue dye through a transurethral catheter into the bladder; a positive test is blue staining of the tampon. If the test is negative, one can evaluate for a ureterovaginal fistula. The patient is given phenazopyridine, which changes the color of urine to orange. If a tampon placed in the vagina stains orange, the test is positive. Alternatively, the patient can be given an intravenous injection of indigo carmine.

Rectal fistula must be considered when a patient reports stool evacuation per vagina. It can be identified in a similar fashion using a large Foley catheter placed in the distal rectum through which dye may be injected or with the use of an oral charcoal slurry and timed examination. Common areas for fistulae are at the vaginal apex, at the site of a surgical incision, or around the site of a prior episiotomy or perineal repair after a vaginal delivery.

BENIGN GYNECOLOGIC CONDITIONS

Many women suffer with undiagnosed symptoms of vulvar disease. Patients presenting with chronic vulvar symptoms should be carefully interviewed, examined, and a vulvar biopsy obtained whenever the diagnosis is in question, the patient is not responding to treatment, or premalignant or malignant disease is suspected. Vulvar conditions such as contact dermatitis, atrophic vulvovaginitis, lichen sclerosis, lichen planus, lichen chronicus simplex, Paget’s disease, Bowen’s disease, and invasive vulvar cancer are not uncommon. Systemic diseases like psoriasis, eczema, Crohn’s disease, Behçet’s disease, vitiligo, and seborrheic dermatitis may also involve the vulvar skin.

This dermatitis is a common cause of acute or chronic vulvar pruritus and can be irritant or allergic.4 Irritant dermatitis usually results from overzealous hygiene habits, such as the use of harsh soaps and frequent douching. It is also common in patients with urinary or fecal incontinence, especially the elderly and the disabled. Allergic vulvar dermatitis is caused by a variety of allergens, such as fragrances and topical antibiotics. The mainstay of treatment is to identify and discontinue the offending agent or practice or providing a skin barrier in the case of incontinence.

There are three types of leukoplakia, a flat white abnormality. Lichen sclerosis is the most common cause of leukoplakia.4 It affects women 30 to 40 years of age. Classically, it results in a figure-of-eight pattern of white epithelium around the anus and vulva resulting in variable scaring and itching and, less commonly, pain. Diagnosis is confirmed with biopsy, and treatment consists of topical steroids. Lichen planus is a cause of leukoplakia with an onset in the fifth and sixth decades of life. Lichen planus, in contrast to lichen sclerosis, which is limited to the vulva and perianal skin, can involve the vagina and oral mucosa, and erosions occur in the majority of patients, leading to a variable degree of scaring. Patients usually have a history and dysuria and dyspareunia and complain of a burning vulvar pain. Histology is not specific, and biopsy is recommended. Treatment is with steroid ointments. Systemic steroids are indicated for severe and/or unresponsive cases. Lichen simplex chronicus is the third cause of leukoplakia but is distinguished from the other lichen diseases by epidermal thickening, absence of scaring, and a severe intolerable itch.4 Intense scratching is not uncommon and contributes to the severity of the symptoms and predisposes the cracked skin to infections. Treatment consists of cessation of the scratching, which sometimes requires sedation; elimination of any allergen or irritant; suppression of inflammation with potent steroid ointments; and treatment of any coexisting infections.

Bartholin’s glands, great vestibular glands, are located at the vaginal orifice at the four and eight o’clock positions; they are rarely palpable in normal patients. They are lined with cuboidal epithelium and secrete mucoid material to keep the vulva moist. Their ducts are lined with transitional epithelium, and their obstruction secondary to inflammation may lead to the development of a Bartholin’s cyst or abscess. Bartholin’s cysts range in size from 1 to 3 cm and are detected on exam or are recognized by the patient. They occasionally result in discomfort and dyspareunia and require treatment. Cysts and ducts can become infected and form abscesses. Infections are often polymicrobial; however, sexually transmitted N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis are sometimes implicated. Treatment consists of incision and drainage and placement of a Word catheter, a small catheter with a balloon tip, for 2 to 3 weeks to allow for formation and epithelialization of a new duct. Appropriate antibiotic therapy should be instituted. Recurrent cysts or abscesses are usually marsupialized, but on occasion necessitate excision of the whole gland. Marsupialization is done by incising the cyst or abscess wall and securing its lining to the skin edges with interrupted sutures.5 Cysts or abscesses that fail to resolve after drainage and those occurring in patients over age 40 should be biopsied to exclude malignancy.

Molluscum contagiosum presents with dome-shaped papules and is caused by the poxvirus. The papules are usually 2 to 5 mm in diameter and classically have a central umbilication. They are spread by direct skin contact and present on the vulva, as well as abdomen, trunk, arms, and thighs. Lesions typically clear in several months but can be treated with cryotherapy, curettage, or cantharidin, a topical blistering agent.

The frequency of the infectious etiologies of genital ulcers varies by geographic location. The most common causes of sexually transmitted genital ulcers in young adults in the United States are, in descending order of prevalence, herpes simplex virus (HSV), syphilis, and chancroid.6 Others infectious causes of genital ulcers include lymphogranuloma venereum and granuloma inguinale. Noninfectious etiologies include Behçet’s disease, neoplasms, and trauma. Table 41-3 outlines a rational approach to their evaluation and diagnosis.

| HERPES | SYPHILIS | CHANCROID | LYMPHOGRANULOMA VENEREUM | GRANULOMA INGUINALE (DONOVANOSIS) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen | Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type II and less commonly HSV type I | Treponema palladium | Haemophilus ducreyi | Chlamydia trachomatis L1-L3 | Calymmatobacterium granulomatis |

| Incubation period | 2–7 days | 2–4 weeks (1–12 weeks) | 1–14 days | 3 days–6 weeks | 1–4 weeks (up to 6 months) |

| Primary lesion | Vesicle | Papule | Papule or pustule | Papule, pustule, or vesicle | Papule |

| Number of lesions | Multiple, may coalesce | Usually one | Usually multiple, may coalesce | Usually one | Variable |

| Diameter (mm) | 1–2 | 5–15 | 2–20 | 2–10 | Variable |

| Edges | Erythematous | Sharply demarcated, elevated, round, or oval | Undermined, ragged, irregular | Elevated, round, or oval | Elevated, irregular |

| Depth | Superficial | Superficial or deep | Excavated | Superficial or deep | Elevated |

| Base | Serous, erythematous | Smooth, nonpurulent | Purulent | Variable | Red and rough (“beefy”) |

| Induration | None | Firm | Soft | Occasionally firm | Firm |

| Pain | Common | Unusual | Usually very tender | Variable | Uncommon |

| Lymphadenopathy | Firm, tender, often bilateral | Firm, nontender, bilateral | Tender, may suppurate, usually unilateral | Tender, may suppurate, loculated, usually unilateral | Pseudo-adenopathy |

| Treatment | Acyclovir (ACV) 400 mg PO tid for 7–10 days for primary infection and 400 mg PO tid for 5 days for episodic management | Primary, secondary, and early latent (<1 year): penicillin G (PCN-G) benzathine 2.4 million U IM × 1 Late latent (>1 year) and latent of unknown duration: PCN-G benzathine 2.4 million U IM every week × 3 | Azithromycin 1 g PO or ceftriaxone 250 mg IM × 1 or ciprofloxacin 500 mg PO bid for 3 days Erythromycin base 500 mg PO tid for 7 days | Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for 21 days or erythromycin base 500 mg PO qid for 21 days | Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for 3 weeks until all lesions have healed |

| Suppression | ACV 400 mg PO bid for those with frequent outbreaks |

Condylomata acuminata (anogenital warts) are viral infections caused by HPV.7 Genital infection with HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States today. HPV types 6 and 11 are the most common low-risk types and are implicated in 90% of cases of genital warts.8 High-risk types can be found in association with invasive cancers. Genital warts are skin-colored or pink and range from smooth flattened papules to verrucous papilliform lesions. Lesions may be single or multiple and extensive. Diagnosis should be confirmed with biopsy because verrucous vulvar cancers can be mistaken for condylomata.9 Treatment modalities range from patient-applied ointments to physician-applied agents and office procedures. If small, self-administered topical imiquimod 5% cream or trichloroacetic acid for in-office applications may be tried. Extensive lesions may require surgical modalities that include cryotherapy, laser ablation, cauterization, and surgical excision.

Paget’s disease of the vulva is an intraepithelial disease of unknown etiology that affects mostly white postmenopausal women in their sixth decade of life. It causes chronic vulvar itching and is sometimes associated with an underlying invasive vulvar adenocarcinoma or invasive cancers of the breast, cervix, or gastrointestinal tract. Grossly, the lesion is variable but usually confluent, raised, erythematous to violet, and waxy in appearance. Biopsy is required for diagnosis; the disease is intraepithelial and characterized by Paget’s cells with large pale cytoplasm. Treatment is assessment for other potential concurrent adenocarcinomas, and then surgical removal by wide local resection of the involved area with a 2-cm margin. Free margins are difficult to obtain because the disease usually extends beyond the clinically visible area.10,11 Intraoperative frozen section of the margins can be done; however, Paget’s vulvar lesions have a high likelihood of recurrence even after securing negative resection margins.

VIN is similar to its cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) counterpart and is graded on the degree of epithelial involvement as mild (VIN I), moderate (VIN II), severe (VIN III), or vulvar carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease).12 Risk factors include HPV infection, prior VIN, HIV infection, immunosuppression, smoking, vulvar dermatoses such as lichen sclerosis, CIN, and cervical cancer. VIN can be unifocal or multifocal. Unifocal lesions commonly affect postmenopausal women and lack a clear association with HPV, while multifocal disease mostly affects younger reproductive-age females and has a strong association with HPV infection. Fifty percent of patients are asymptomatic, with vulvar pruritus being the most common complaint in those with symptoms. Lesions may be vague or raised and velvety with sharply demarcated borders. Diagnosis is made with a vulvar skin biopsy, and multiple biopsies are sometimes necessary. Colposcopy with application of 5% acetic acid and identification of the acetowhite lesions of VIN is a valuable diagnostic tool for subtle lesions and will help guide the biopsy. Evaluation of the perianal and anal area is important as the disease may involve these areas, particularly in immunocompromised and/or nicotine-addicted women. Once invasive disease is ruled out, treatment usually involves wide surgical excision; however, the initial treatment approach may include 5% imiquimod cream, CO2 laser ablation, or cavitational ultrasonic surgical aspiration, and depends on the number of lesions and their severity. When laser ablation is used, a 1-mm depth in hair-free areas is usually sufficient, whereas hairy lesions require ablation to a 3-mm depth because the hair follicles’ roots can reach a depth of 2.5 mm. Unfortunately, VIN tends to recur in up to 30% of cases, and high-grade lesions (VIN III, carcinoma in situ) progress to invasive disease in approximately 10% of patients if left untreated.13

(see Table 41-2).

Vulvovaginal symptoms are extremely common, accounting for over 10 million office visits per year in the United States. The causes of vaginal complaints are commonly infectious in origin, but they include a number of noninfectious causes, such as chemicals or irritants, hormone deficiency, foreign bodies, systemic diseases, and malignancy. Symptoms are commonly nonspecific and include abnormal vaginal discharge, pruritus, irritation, burning, odor, dyspareunia, bleeding, and ulcers. A purulent discharge from the cervix should always raise suspicion of these infections even in the absence of pelvic pain or other signs.

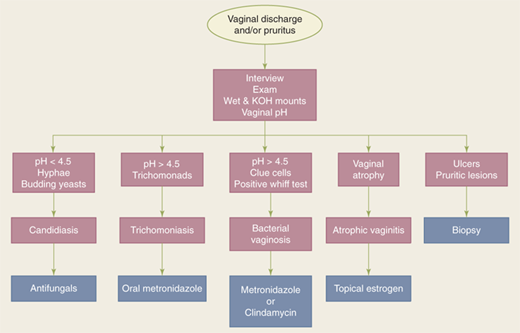

Normal vaginal discharge is white or transparent, thick, and mostly odorless. It increases during pregnancy, with use of estrogen-progestin contraceptives, or at mid-cycle around the time of ovulation. Complaints of foul odor and abnormal vaginal discharge should be investigated. Candidiasis, bacterial vaginosis, and trichomoniasis account for 90% of vaginitis cases. The initial workup includes pelvic examination, vaginal pH testing, microscopy, vaginal cultures if microscopy is normal, and gonorrhea/chlamydia NAAT (see earlier section, Common Screening and Testing).14 The pH of normal vaginal secretions is 3.8 to 4.4, which is hostile to growth of pathogens. A pH greater than or equal to 4.9 is indicative of a bacterial or protozoal infection. Treatment of vaginal infection before anticipated surgery is appropriate, particularly for bacterial vaginosis, which may be associated with a higher risk for vaginal cuff infections (Fig. 41-8).

BV accounts for 50% of vaginal infections. It results from reduction in concentration of the normally dominant lactobacilli and increase in concentration of anaerobic organisms like Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, Bacteroides species, and others.15 Diagnosis is made by microscopic demonstration of clue cells. The discharge typically produces a fishy odor upon addition of KOH (amine or Whiff test). Initial treatment is usually a 7-day course of metronidazole.

VVC is the most common cause of vulvar pruritus. It is generally caused by Candida albicans and occasionally by other Candida species. It is common in pregnant women, diabetics, patients taking antibiotics, and immunocompromised hosts. Initial treatment is usually with topical antifungals, although single-dose oral antifungal treatments are also common.

Trichomoniasis is a sexually transmitted infection of a flagellated protozoan and can present with malodorous, purulent discharge. It is typically diagnosed with visualization of the trichomonads during saline wet mount microscopy. Initial treatment is usually a 7-day course of metronidazole.

A Gartner’s duct cyst is a remnant of the Wolffian tract; it is typically found on the lateral vaginal walls. Patients can be asymptomatic or present with complaints of dyspareunia or difficulty inserting a tampon. If symptomatic, these cysts may be surgically excised or marsupialized. If surgery is planned, a preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan should be obtained to determine the extent of the cyst.

The etiology and treatment of vaginal condyloma is similar to vulvar condyloma (see earlier section, Vulvar Condyloma).

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia, or VaIN, is similar to VIN and is classified based on the degree of epithelial involvement as mild (I), moderate (II), severe (III), or carcinoma in situ.12 Sixty-five percent to 80% of VaIN or vaginal cancers are associated with HPV infection. The majority of lesions are located in the upper one third of the vagina. Lesions are usually asymptomatic and found incidentally on cytologic screening. Diagnosis is made via guided biopsy of acetowhite lesions at the time of colposcopy. Lesions may appear flat or raised and white with sharply demarcated borders and may show vascular changes. The presence of aberrant vessels with marked branching is suggestive of invasive disease. VaIN is treated with laser ablation, surgical excision, or topical 5-fluorouracil therapy.

Benign lesions of the cervix include endocervical polyps, Nabothian cysts (clear, fluid-filled cysts with smooth surfaces), trauma (such as delivery-related cervical tear or prior cervical surgery), malformation of the cervix, and cervical condyloma. For endocervical polyps, exploration of the base of the polyp with a cotton swab tip to identify that it is cervical and not uterine and to identify the stalk characteristics can help identify the appropriate surgical approach. Small polyps with identifiable base can be removed by grasping the polyp with ring forceps and slowly rotating it until separated from its base. Use of loop electro-excisional procedure (LEEP) is appropriate for larger lesions. Laser or other ablative procedures are appropriate for condyloma proven by biopsy.

High-grade cervical dysplasia (CIN II or III) has a high chance of persistent HPV infection with risk of transformation to malignancy; thus an excisional procedure is usually indicated. This serves a therapeutic purpose by removal of dysplastic cells and a diagnostic purpose for histologic review to rule out concomitant early-stage cervical cancer. Either a LEEP or cold knife conization (CKC) may be used for surgical excision of the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) and outer endocervical canal. Risks of both procedures include bleeding, postprocedure infection, cervical stenosis, and risk of preterm delivery with subsequent pregnancies. A looped wire attachment for a standard monopolar electrosurgical unit is used to perform a LEEP excision. Loops range in a variety of shapes and sizes to accommodate different sizes of cervix. Optimally, one pass of the loop should excise the entire SCJ. Hemostasis of the remaining cervix is achieved with the ball electrode and ferrous sulfate paste (Monsel’s solution).

Different from a LEEP, a cervical CKC does not use energy to excise the specimen. The advantage of this procedure is that the margin status is not obscured by cauterized artifact. This is important in cases of adenocarcinoma in situ and microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma, where margin status dictates the type of and indication for future therapy. During a CKC, a #11 blade is used to circumferentially excise the conical biopsy. Hemostasis is achieved with the ball electrode, Monsel’s solution, or suture.

Two HPV vaccines have been developed and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).16 Gardasil is a quadrivalent vaccine that targets HPV genotypes 16 and 18, which cause approximately 70% of cervical cancers and about 50% of precancerous lesions (CIN II/III) worldwide, and HPV genotypes 6 and 11, which cause 90% of genital warts. Cervarix is a bivalent vaccine that targets HPV genotypes 16 and 18. In contrast to natural infection, the vaccine is highly immunogenic, activating both humoral and cellular immune responses. Vaccination generates high concentrations of neutralizing antibodies to HPV L1 protein, the antigen in both vaccines. It is thought that vaccination may provide protection against HPV infection through neutralization of virus by serum immunoglobulin that diffuses from capillaries to the genital mucosal epithelium.17

Several randomized clinical trials18,19,20 involving approximately 35,000 young women have shown that both Gardasil and Cervarix prevent nearly 100% of the HPV subtype-specific precancerous cervical cell changes for up to 4 years after vaccination among women who were not infected at the time of vaccination; vaccination occurred before sexual debut. These major clinical trials have used prevention of CIN II/III and carcinoma in situ as the efficacy endpoints. Vaccination has not yet been shown to protect women who are already infected with HPV-16 or HPV-18 at the time of vaccination.

Current FDA approval applies to use in women who are between 9 and 26 years of age for the prevention of the following: cervical, vulvar, and vaginal cancer caused by HPV-16 or -18, genital warts caused by HPV-6 or -11, and lesions caused by HPV-6, -11, -16, or -18 (CIN I, II, and III; cervical carcinoma in situ; VIN; or VaIN II/III). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends routine vaccination for females 11 to 12 years of age, maybe starting at age 9; catch-up vaccination is recommended for females 13 to 26 years of age who did not get all three doses when they were younger. Studies to evaluate the efficacy of the vaccine in healthy women 26 years of age and older with no prior exposure to HPV is ongoing, and additional information on the length of protection is forthcoming. In 2009, the FDA approved the quadrivalent vaccine for use to prevent genital warts in men and boys, and in 2011, the ACIP recommended that all males 11 to 12 years of age be vaccinated, stating that this may reduce some of the HPV-related burden suffered by women.

Immunocompromised women may receive the quadrivalent vaccine. Although the safety and immunogenicity of HPV vaccination in this population are not well established, the vaccine could be beneficial in these women since they are at increased risk for HPV-related cancers. Vaccination is not recommended for pregnant women, although neither vaccine has been shown to be causally associated with adverse outcomes in pregnant women or their fetuses. If pregnant women are vaccinated inadvertently, completion of the series should be delayed until after the pregnancy.

Cervical cancer screening continues to play an important role in detection and treatment of CIN II/III and prevention of cervical cancer in these high-risk patients. Cervical cancer screening continues to be of great importance since HPV immunization will not prevent approximately 25% to 30% of cervical cancers in HPV-naïve women and does not protect against the development of cancer in women already infected with carcinogenic HPV types.

The average age of menarche, or first menstrual period, in the United States is 12 years and 5 months. Duration of normal menstruation is between 2 and 7 days, with a flow of less than 80 mL, cycling every 21 to 35 days.21 Nonpregnant patients, who present with heavy bleeding and are 35 years of age and older or have risk factors for endometrial cancer, must be ruled out for malignancy as the first step in their management (see earlier section, Endometrial Biopsy).

Abnormal uterine bleeding is described based on the bleeding pattern. Menorrhagia is prolonged (>7 days) or excessive (>80 mL daily) menstrual cycles occurring at regular intervals, and metrorrhagia is bleeding between menstrual periods. Menometrorrhagia is the occurrence of both. Intermenstrual bleeding, also known as spotting, is bleeding of variable amounts occurring between regular menstrual cycles. Poly-, oligo-, and amenorrhea are menstrual cycles of less than 21 days, longer than 35 days, or the absence of uterine bleeding for 6 months or a period equivalent to three missed cycles, respectively. Because there are many causes of AUB, they are divided into two categories: structural causes and nonstructural causes.22 Structural causes include polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyomata, and malignancy. Nonstructural causes can include coagulopathy, ovulatory dysfunction, endometrial effects, and iatrogenic causes.

Endometrial polyps are localized hyperplastic growth of endometrial glands and stroma around a vascular core forming sessile or pedunculated projections from the surface of the endometrium.23 Endometrial polyps are rarely neoplastic (<1%) and may be single or multiple. Many are asymptomatic; however, they are responsible for about 25% of cases of abnormal uterine bleeding, usually metrorrhagia. Polyps are common in patients on tamoxifen therapy and in peri- and postmenopausal women. Up to 2.5% of patients with a polyp may harbor foci of endometrial carcinoma.24 Diagnosis can be made with saline-infused hysterosonography, hysterosalpingogram, or direct visualization at the time of hysteroscopy. Definitive treatment, in the absence of malignancy, involves resection with an operative hysteroscope or by sharp curettage.

Adenomyosis refers to ectopic endometrial glands and stroma situated within the myometrium. When diffuse, it results in globular uterine enlargement secondary to hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the surrounding myometrium. Adenomyosis is very common, tends to occur in parous women, and is frequently an incidental finding at the time of surgery. Diagnosis is suspected in a parous woman with menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, and diffuse globular uterine enlargement. MRI may reveal islands within the myometrium with increased signal intensity.25 Hysterectomy is the only treatment, providing material for definitive pathologic diagnosis.

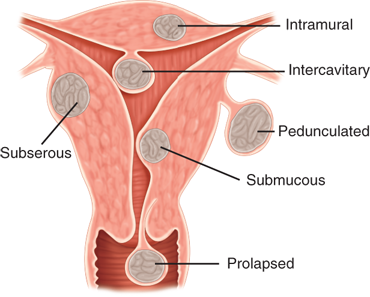

Leiomyomas, also known colloquially as fibroids, are the most common female pelvic tumor and occur in response to growth of the uterine smooth muscle cells (myometrium). They are common in the reproductive years, and by age 50, at least 60% of white and up to 80% of black women are or have been affected. Leiomyomas are described according to their anatomic location (Fig. 41-9) as intramural, subserosal, submucosal, pedunculated, cervical, and rarely ectopic.21 Most are asymptomatic; however, abnormal uterine bleeding caused by leiomyomas is the most common indication for hysterectomy in the United States. Other manifestations include pain, pregnancy complications, and infertility. Pain generally results from degenerating myomas that outgrew their blood supply or from compression of other pelvic organs such as the bowel, bladder, and ureters. High levels of pregnancy hormones frequently cause significant enlargement of pre-existing myomas, which may lead to significant distortion of the uterine cavity resulting in recurrent miscarriages, fetal malpresentations, intrauterine growth restriction, obstruction of the birth canal and the subsequent need for cesarean delivery, abruption, preterm labor, and pain from degeneration.

Bleeding is usually heavy and irregular (menometrorrhagia) and can be severe at times, requiring hospitalization. Examination reveals an enlarged irregular uterus and, in severe cases, a large solid pelvic mass extending to the upper abdomen. Diagnosis is usually made by transvaginal ultrasonography. Other diagnostic modalities, including MRI, computed tomography (CT), and hysterosalpingogram or saline-infused hysterosalpingography, are especially useful in the cases of submucosal and intrauterine myomas. Most are benign; malignant degeneration occurs in less than 1% of cases and is usually encountered in the menopausal years. Management options of leiomyomas are tailored to the individual patient depending on her age and desire for fertility and the size, location, and symptoms of the myomas. Conservative management options include oral contraceptive pills, medroxyprogesterone acetate, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, uterine artery embolization, and myomectomy.26,27,28 Uterine artery embolization is contraindicated in patients planning future pregnancy and frequently results in acute degeneration of myomas requiring hospitalization for pain control. Myomectomy is indicated in patients with infertility and those who wish to preserve their reproductive capacity. Hysterectomy is the only curative therapy. Treatment with GnRH agonists for 3 months prior to surgery is recommended in anemic patients and may allow them time to normalize their hematocrit, avoiding transfusions; GnRH also decreases blood loss at hysterectomy and shrinks the myomas by an average of 30%. The latter may make the preferred vaginal surgical approach more feasible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree