KEY POINTS

There are five major forces reshaping priorities and strategies for the globalization of surgical care:

The epidemiologic transition of diseases

The mobile nature of the world’s populations

Ubiquitous information access

A revolution for equity and human rights

Recognition of the cost-effectiveness of surgical care

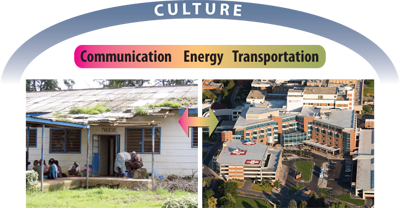

Understanding and addressing the necessary communication, energy and transportation technologies along with the underlying cultural context represent the foundation critical to implementing sustainable infrastructure necessary for appropriate surgical care.

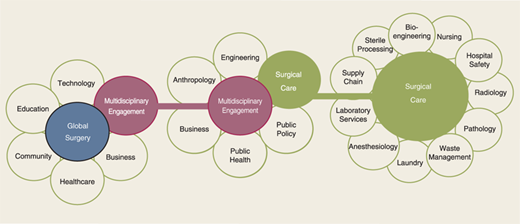

The key components of the global surgery ecosystem include technology, education, community, healthcare, business, and multidisciplinary engagement between a variety of disciplines.

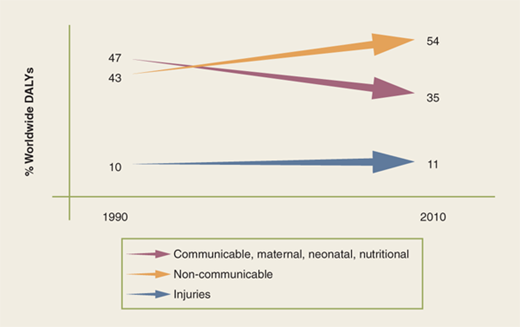

There has been a significant shift from communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional causes to noncommunicable causes, many of which require surgical care.

Patients and their communities in low-middle income countries (LMICs) bear a much greater share of the burden of cancer than high-income countries.

Globally, trauma has become a leading cause of death and disability; 90% of trauma deaths occur in LMICs.

The burden of disease is greatest in areas where human resources—physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare workers—are the least.

Surgery is gaining an increasingly recognized role for improving public health.

Surgery has a role in prevention as well as treatment.

The cost-effectiveness of various aspects of surgical care has allowed surgical initiatives to be included when prioritizing public health initiatives.

Developing advanced surgical capabilities in resource-poor countries has the potential to decrease overall cost and actually develop the infrastructure necessary to entice physicians and other healthcare workers to remain in their own countries.

Academic involvement in global surgery provides training for the next generation of surgical leaders.

Surgical innovations that consider cost as well as quality and design for challenging energy environments will foster equity in surgical care for LMICs.

INTRODUCTION

Modern surgery can save lives, help expand economies, and offer hope to individuals and communities. Prior to the acceptance and availability of aseptic technique to prevent or decrease infections, and improved anesthesia for controlling pain, surgery as a specialty was held in very low esteem. Over the last 100 years, surgery has developed into an elite discipline that not only provides opportunities for curing certain diseases, but fulfills a special role in preventing and mitigating disability.

Yet, surgery is currently unavailable to most people worldwide. The vast majority—90%—of the world’s population receives only 10% of the surgical care delivered. Said another way, 90% of the world’s surgical resources are consumed by the most privileged 10% of the world’s population. More than 2 billion people lack access to even basic surgical care.1 Very few surgical procedures occur in countries spending less than US $100/ person on health care per year compared to countries spending greater than U.S. $1000/ person (Fig. 49-1).2

Figure 49-1.

Worldwide distribution of surgical procedures. (Data from Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modeling strategy based on available data. Lancet. 2008;372(9633):139-144. Illustration reproduced with permission from Intermountain Healthcare.)

Examples of disparities abound. In many countries, including the wealthiest, deep pockets of poverty coexist within cities replete with material resources. Tertiary level hospitals operate within eyesight of slums whose inhabitants have no access to even basic care. Most of the people without access—people in rural areas and in countries with poor infrastructure—are the very people most at risk for death or disability due to lack of surgical care. Often the poor accept and endure many painful and potentially correctable fatal conditions as a fact of life.3,4,5,6 Care for trauma and obstetrical emergencies are considered basic surgical needs but are absent in many rural regions. Other chronic conditions—often equally debilitating—progress to death or serious disability due to lack of available, safe surgery and anesthesia.

Many factors contribute to the disparity in access to surgical care. Poverty, a primary risk factor for all types of diseases, is a major obstacle hindering access to surgery. Healthcare professionals, including surgeons, migrate from areas of need due to a lack of infrastructure (hospitals, roadways, and stable electrical sources), limited supplies and equipment, lack of human resources, few opportunities for professional development, and concerns for personal safety. Finally, the lack of information about the burden of surgical disease and surgery’s impact on communities has led to misconceptions of policy makers that quality surgical care is cost prohibitive and too complex to be seriously considered a viable conduit for improving global health.7,8

Disparities in care and outcomes are multidimensional, and no simple solution exists to improve access to appropriate and affordable surgical care. Yet, five major forces are reshaping priorities and strategies leading the charge for the globalization of surgical care:

The epidemiologic transition of diseases from primarily infectious to more chronic conditions;

The mobile nature of the world’s populations allows more convenient travel opportunities for people to move freely between more isolated areas of the world leading to a more integrated global community;

Ubiquitous information access exponentially enabling universal participation in understanding and designing innovative opportunities for high-quality surgical care;

A revolution for equity and human rights where the world’s poor are demanding benefits to surgical care similar to those found in developed countries;

Recognition of the cost-effectiveness of surgical care, and its potential to build economies, demonstrating the potential value of, including surgery in global health strategies.9,10

The potential benefits of surgical care for economic productivity are astounding. Considering that the annual economic loss from road traffic injuries alone exceeds U.S. $500 billion globally, a panel of expert economists at the Copenhagen Consensus of 2012, including four Nobel prize laureates, understandably prioritized strengthening surgical capacity as the eighth most cost-effective investment for addressing the world’s current most pressing problems.8,11 Good health, which fosters productive economies and political stability, must include access to the full spectrum of health care, including surgical care to “advance the quality of life for billions of citizens around the world.”8

This chapter examines the need for expanding surgical care globally, explores some of the seemingly insurmountable challenges, and presents potential guiding concepts along with examples of successful strategies for sustainable surgical development.

DEFINING GLOBAL SURGERY

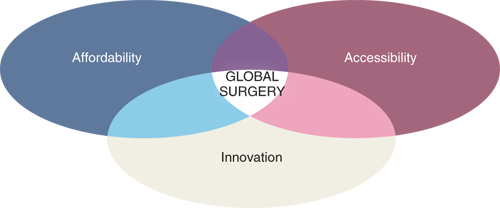

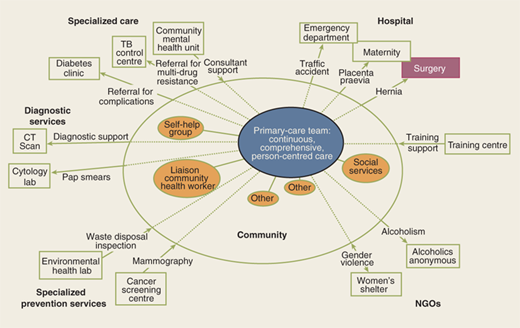

To understand how surgery fits into healthcare systems and to understand its unique needs, it is helpful to consider global surgery as an ecosystem. The emerging field of global surgery considers surgical care to be a fundamental component of global health. As a system with both local and international scope, global surgery encompasses not just the medical and technical aspects of surgical care but also the societal and environmental context in which surgery is performed. Surgery as an ecosystem considers the diverse but interrelated systems that must be functional for quality surgical care to be delivered. Only part of these systems falls within the traditional training of surgeons. Yet, modern surgical care requires these systems to work in a coordinated fashion to support three priorities critical for expanding surgery globally—accessibility, affordability, and innovation (Fig. 49-2). Global surgery is a way to consider a “systems-based practice” beyond a single hospital or community for the benefit of people worldwide. Many of the interrelated components of this surgical ecosystem originate outside the hospital.

Disparities in surgical care have geographical, socioeconomic, and cultural components. Most people who live in major cities in northern and western hemisphere countries take for granted a functioning energy grid. The development of energy beyond major cities has enabled many wealthier communities to imagine, and indeed, to expect healthcare to be available at all times and to be affordable. Yet, a lack of reliable energy sources is a major limiting factor. Communication and transportation technologies, for example, the mobile phone and air and ground travel, have dramatically progressed in high- and middle-income countries but are still rudimentary in poor countries. Many of the current disparities in health care, particularly surgical care, are due to the lack of penetration of these technologies. Understanding and addressing the necessary communication, energy and transportation deficits as well as the underlying cultural nuances are necessary to support the sustainable development of surgical care (Fig. 49-3).

Electricity is necessary for all modern surgery. Anesthesia monitoring, OR lighting, cautery, suction, and patient warming devices all require sources of electricity that are stable, without huge electrical surges. Only in the last 50 years or so could stable electricity be expected in most wealthy cities. However, in rural areas of even wealthy countries, electricity remains unpredictable (Fig. 49-4).

In poorer countries, the cost and availability of electricity is frequently the limiting factor for more advanced diagnostic and therapeutic technology—from laboratories that require refrigeration to radiology in all of its various branches. Modern design for surgical devices has, for the most part, not taken into account the wide range of energy environments where surgery is practiced. Fragile instruments and monitors that cannot survive the rigors of the real working environment limit the types of surgery that can be provided.

Improvements in energy, transportation, and communication are critical to support the growth of six key components of surgical care (Fig. 49-5).9 While building capacity within each component is important, it is the interaction between the components that creates a functioning, sustainable system.

When surgeons think of surgery, they usually think in terms of science and hands-on technical expertise. However, global surgery requires a broader understanding of systems in other disciplines. Surgeons must work collaboratively with engineers and business leaders to develop technology that can function in lower resource environments. These innovations can provide a source of economic growth for the community, which in turn supports better health care.

No sustainable surgical system in the modern age can function without specialists in bioengineering, sterile process, supply chain, hospital safety and waste management. These often unappreciated colleagues make possible the daily practice of surgery. Similarly, specialists in anesthesia, nursing, and the diagnostic specialties of radiology, pathology, and laboratory services are fundamental to a fully functional surgical service.

The population on Earth currently stands at more than 7 billion.While the rate of growth has slowed in recent years, projections estimate that the population will continue to grow to 9 billion by 2050.12 When thinking about global surgery, it is helpful to step back from the individual and consider families, communities, and nations. Each entity has its unique cultural and economic history and geographic advantages or disadvantages. Each has its own system for addressing surgical care but operates within a larger ecosystem, including energy availability, telecommunications and social networks, an interdependent global economy, and local material resources.

Population characteristics are changing rapidly. According to United Nations estimates, the human population of the entire world is aging, even in low-income countries, and by 2050, 2 billion people will be over the age of 60. Currently, Asia is home to 55% of the world’s population over the age of 60.13 Until recently, infectious diseases dominated public health strategy. Now with major scourges like polio isolated to relatively small regions of the world and HIV and malaria decreasing in their relative impact worldwide, chronic diseases and their complications, as well as the effects of aging, are gaining dominance in health care needs. Many of these chronic diseases are best approached by surgery.

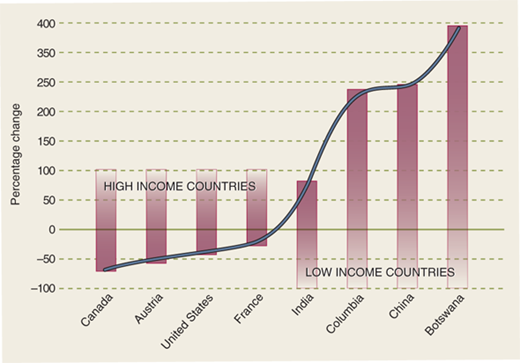

The lack of metrics and paucity of data identifying the unmet burden of surgical need in many countries have been obstacles facing global surgery initiatives. The 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study was the first worldwide comprehensive burden of disease evaluation since the initial 1990 epidemiologic study. Using the disability-adjusted life years (DALY), a metric initially proposed for the 1990 study that captures both premature mortality and the prevalence and severity of illnesses, disease burdens were calculated for 291 causes in 21 regions of the world (including 187 countries) for 1990, 2005, and 2010 to enable identification of significant trends over time.14 While the global DALYs remained stable from 1990 to 2010, the study identified a significant shift from communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional causes to noncommunicable causes (Fig. 49-6).15

Figure 49-6.

Shift in disease burden 1990–2010. (Data from Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197-2223. Illustration reproduced with permission from Intermountain Healthcare.)

In the 2006 Disease Control Priorities 2nd edition, the global burden of premature death and disability from surgically treatable conditions was estimated at 11% of the total global burden of disease.10 Recently, country-wide population surveys using the Surgeons OverSeas Assessment of Surgical Need (SOSAS) methodology identified a large unmet burden of surgical disease. In Sierra Leone, 25% of deaths of household members during the previous year might have been averted by timely surgical care; 25% of respondents also reported a current condition needing surgical attention.16. In Rwanda, in 2011, the SOSAS survey found 41.2% of the population had at least one operative condition during their life time; 6.4% of the population was found to have a current surgically treatable condition.17 Using the percentage of the population currently needing surgical care from Rwanda and Sierra Leone combined with the 2012 population in Sub-Saharan Africa of almost 900 million, there are between 56 million and 218 million people just in Sub-Saharan Africa needing surgical attention today! Untreated acute and chronic surgical conditions represent a significant unmet burden of disease that have major impact on the economies of these nations.18

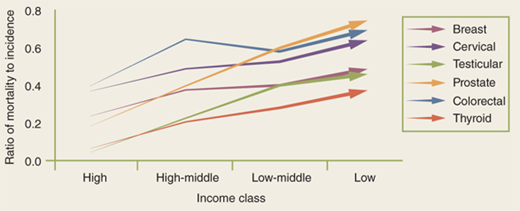

Patients and their communities in low- and middle-income countries(LMICs) bear a much greater share of the burden of cancer than high-income countries. The dramatic increase in the proportion of reported cancer cases in LMICs is a result of population growth, aging populations, and the decreased mortality from infectious diseases. In 1970, only 15% of newly reported cancer cases worldwide were from the developing world; by 2008, this proportion rose dramatically to 58% and is expected to grow to 70% by 2030.19 Previously thought to be a disease almost exclusive to high-income countries, nearly two-thirds of the 7.6 million cancer deaths worldwide occur in LMICs. Mortality from cancer correlates inversely with a country’s economy for certain treatable cancers, including breast, testicular, and cervical cancer—LMICs have higher case fatality rates than high-income countries (Fig. 49-7).19,20

Figure 49-7.

Ratio of mortality to incidence by solid tumor type and country income (2008). (Data from Farmer P, Frenk J, Knaul FM, et al. Expansion of cancer care and control in countries of low and middle income: a call to action. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1186-1193. Illustration reproduced with permission from Intermountain Healthcare.)

For example, breast cancer case fatality rates illustrate the great disparity in outcomes between regions. Case fatality rates in East Africa reach an unacceptable 59% compared to 19% in the United States.20 In LMICs, patients have very limited access to screening. They present for care with much later stages of cancer. In Haiti, after the great earthquake, in 2010, and after the initial onslaught of orthopedic injuries, many aid organizations found themselves faced with the unmet underlying burden of disease, including late stage breast cancer and other tumors(Fig. 49-8).

Trauma has become a leading cause of death and disability around the world; 90% of trauma deaths occur in LMICs.21 Approximately 32% more people die as a result from injuries than from malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS combined representing 10% of the world’s deaths (Fig. 49-9).22,23 In the United States, a patient presenting with an injury in a rural community has a higher mortality than those from an urban setting.24 This disparity is much more pronounced in economically disadvantaged societies where seriously injured patients from road traffic accidents are twice as likely to die compared to similarly injured patients in a high-income setting (Fig. 49-10).22,25 Additionally, death is much more likely to occur in the pre-hospital settings for injured patients from low-income countries. The lack of integrated communication and emergency transportation systems contribute to the pre-hospital risk, while the lack of infrastructure, supplies, and personnel contribute to in-hospital mortality.

Almost 11 million people worldwide sought medical or surgical care related to burns in 2004. However, the vast majority of burned people never present for medical care. Burns represent a significant cause of death as well as disability globally.26 The vast majority of deaths from fires (95%) occur in LMICs. Burns result in nearly 200,000 deaths each year from fires while other forms of burns, including scalds and electrical burns, represent another significant source of death and disability. Women and children in LMICs are most likely to be burned in domestic kitchens; men are more likely to be burned in the workplace. The economic and social impact from long hospitalizations and from the resulting disfigurement provides a significant negative stigma causing ostracism and rejection.

Of all the forms of trauma worldwide, burns are the only type that predominantly afflicts women and children. Southeast Asia accounts for 27% of the burn-related deaths worldwide; 70% of people dying from burns in the region are women.27 Cooking on wood, charcoal, or low kerosene stoves also puts children at risk, particularly from scalding (Fig. 49-11). Small children in the WHO African region have triple the number of burn deaths as children worldwide. Contrast this with the United States, where more burns and burn deaths affect men.

People living in rural areas suffer disproportionately because there are fewer facilities capable of managing the acute and chronic aspects of burn management and because the population is generally poorer. Surgical grafting and management of contractures is often best done in specialized burn centers, but these are rare in LMICs. Telemedicine has been shown to be effective in managing burns and preventing complications.28

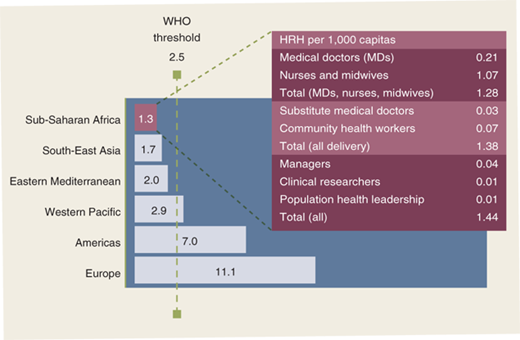

The greatest burden of disease occurs in areas where human resources—physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare workers—are scarce (Fig. 49-12).29 The proportion of physicians is low both in high population areas and in areas where the population is growing most rapidly (Fig. 49-13).30,31 Fully trained surgeons and anesthesiologists comprise only a small proportion of the total number of the Human Resources in Health (HRH). In the Eastern Mediterranean, Southeast Asia, and Africa, HRH per 1000 people falls below the WHO minimum threshold (Fig. 49-14).29 Many countries in Africa—for example Tanzania and Ethiopia—have only 0.6 surgeons per 100,000 population while the United States and Canada have 51 and 26 surgeons per 100,000 population, respectively.32 To provide the same concentration of surgeons in East Africa that currently exists in Canada would require training an estimated additional 42,000 surgeons.33

Figure 49-13.

Number of physicians, world populations, and world population growth rates. (Figure Created from Data: Number of physicians per 10,000 population, 2005-2010, WHO, World Health Statistics 2012, available at: . See also, WHO, Global Health Observatory, available at: ; Population 2012, Sources:CIA, The World Factbook, available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/.)

Primary care physicians, nurses, midwives, or advanced care practitioners (ACPs) provide much of the basic surgical and anesthetic care in LMICs. Where regulations allow, “task shifting,” or training ACPs to deliver surgery and anesthesia services previously allowed only under the purview of fully trained specialists, can provide expanded access to care.34,35,36 Non-M.D. practitioners, variously known as assistant medical officers (AMOs) or “tecnicos de cirurgia” in Mozambique, often have extensive operative experience, including obstetrical care and are the primary providers of surgical care in a region.37,37,38 Task shifting to ACPs also occurs in the United States and other countries where they fill a need otherwise unmet by specialists even in major tertiary care centers.39 However, concerns about the quality of care, lack of adequate supervision, and the effect on prestige and professional development for specialists and ACPs, continue to be topics for debate.40

Migration of practitioners to economically and culturally favorable locales is universal and not restricted to low-resource countries.41 However, the net impact on poor countries is greater. In a 2004 study, more than 23% of U.S. physicians received their medical training from other countries; of these 64% were from low-income countries.42 Investments in training greater numbers of doctors in these countries, including surgical specialists, have been only partially successful in meeting the demand in poor countries. Until economic conditions improve or opportunities for professional development increase, and incentives enticing migration of health care workers to high-income countries abate, it is unlikely that the most skilled practitioners will remain in resource-poor areas beyond their immediate obligations.43,44,45,46,47

STRATEGIES FOR DEVELOPMENT

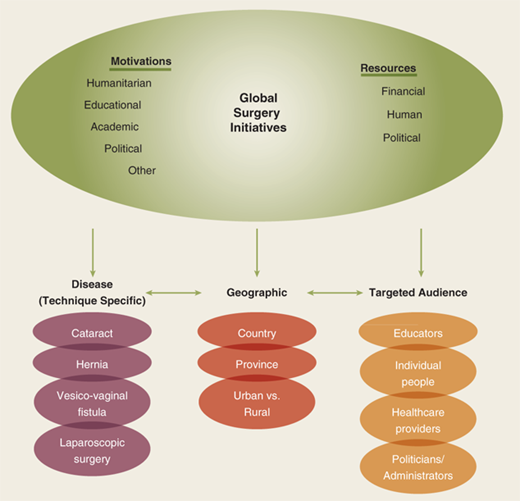

Many models for outreach and engagement have had a positive impact on the accessibility of surgery. Organizations participating in outreach are guided by a wide range of motivations and resources (Fig. 49-15). Some organizations are purely humanitarian and service oriented; others are primarily educational. Some even use the promise of healthcare to advance political, religious, or personal agendas.

Responding to the challenges of disparities, new generations of students, faculty, philanthropists, private industry leaders and policy makers have demonstrated a growing passion to address global surgery as part of global health. Prior to 1984 only 0.32% of physicians and 0.12% of nurses were involved in international health (either paid or volunteer).48 Recently, interest in global health has exploded among medical students in the United States. A 2009 survey indicated that 25% of U.S. medical students have traveled to LMICs for clinical and research electives. At some medical schools the number has risen to over 50%.49,50 In 2004, 40% of medical students in the United Kingdom spent their 6 to 12 week elective rotation in developing countries.51 A structured questionnaire was administered anonymously to all American College of Surgeons resident members. Approximately 94% of the respondents were general surgery residents, and 92% were interested in an international elective with many planning to volunteer in the future.52

Many patients have benefited from the multitude of service-oriented volunteer “missions” providing much needed surgical care that would otherwise have been unavailable. While volunteerism and medical missions are laudable activities, they are not a sustainable solution to long-term manpower shortages for health.53 Comprehensive initiatives are also necessary to engage local healthcare professionals and organizations, governments, and academic institutions to build capacity at home.54

Committed to maintaining international peace, developing friendly relations between nations, and promoting better standards of living (conquering hunger, disease, and illiteracy) and human rights, representatives from 51 nations in 1945 signed the United Nations Charter at the United Nations Conference on International Organization held in San Francisco, California.55 There are now 193 member states.56 The UN promotes a social justice agenda advocating for worldwide health, engagement of philanthropies and civil society in global health initiatives, and supports the Millennium DevelopmentGoals (MDGs).

Leaders from 189 countries gathered at the UN headquarters in September 2000 and agreed on eight specific “Millennium Development Goals” (Table 49-1).57 Some have argued that strengthening basic surgical care at district level hospitals is critical to reaching MDGs 4, 5, and 6 (reducing child and maternal mortality and halting and reversing the spread of AIDS).6,58 In poor countries, the enormous shortfalls in infrastructure, and human and material resources severely limits the capabilities to provide access to life-saving and life-changing services such as timely Cesarean-section, control of peri-partum hemorrhage, appropriate care for pediatric trauma, and treatment for a multitude of congenital diseases.3,59,60,61,62,63,64 While the evolution of public policy has been slow to accept surgical care as integral to poverty reduction and public healthcare, surgeons are actively campaigning for and joining the process of negotiating for inclusion of surgical care development into the new post-2015 to 2030 MDGs.65

|

The initial UN Conference in 1945 voted to establish a new international health organization. The Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO) was approved and ratified in 1948.55 The first World Assembly in 1948 established malaria, tuberculosis, venereal diseases, maternal and child health, sanitary engineering, and nutrition as WHO priorities. One of the WHO’s greatest public health stories is the worldwide eradication of smallpox that began with the USSR proposal for the WHO-led program in 1958 culminating in the last identified case in Somalia in 1977.

While the disease burden from communicable diseases has abated in large part from these successful international cooperative interventions, little has been done to address the growing global burden of surgical disease. Despite the laudable 1978 Declaration of Alma Alta that expressed the need for urgent action for the world community to protect and promote the health for all people, the declaration did so by crowning primary health care as the key to achieving the goal of health for all—which was then accepted by the member countries in the World Health Organization.66 Although the Alma-Ata slogan “Health for all by 2000” did not materialize, it did galvanize efforts for global partnerships for healthcare improvements and poverty reduction.

The Violence and Injury Prevention Program (VIP) and the Global Initiative for Emergency and Essentials Surgical Care (GIEESC) are two programs related to surgery within the WHO that began before 2008. But, as a response to a growing recognition of the significant unmet surgical need, in 2008, the WHO for the first time included basic surgery as a component for community primary health care(Fig. 49-16).67

The Clinical Procedures (CPR) team in the WHO Department of Essential Health Technologies (EHT) convened a multidisciplinary group of experts from various surgical disciplines, professionals and civic leaders from national and international organizations, and representative from various WHO departments in December 2005 in Geneva, Switzerland, to formally organize the GIEESC.68

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree