Getting Evidence into Action

Evidence Utilization

|

This component of the model relates to the implementation of evidence in practice, as is evidenced by practice and/or system change. It identifies three elements: evaluating the impact of the utilization of evidence on the health system, the process of care and health outcomes; practice change; and embedding evidence through system/organizational change.

It is now well recognized that multiple interventions may be more effective than single interventions in evidence utilization programs, and that implementation is complex (Grimshaw, et al. 2001; NHS CRD, 1999). CRD state that evidence indicates a need for the following steps to be pursued in programs designed to utilize evidence:

“A ‘diagnostic analysis’ to identify factors likely to influence the proposed change. Choice of dissemination and implementation interventions should be guided by the ‘diagnostic analysis’ and informed by knowledge of relevant research”.

“Multi-faceted interventions targeting different barriers to change are more likely to be effective than single interventions”.

“Any systematic approach to changing professional practice should include plans to monitor and evaluate, and to maintain and reinforce any change”.

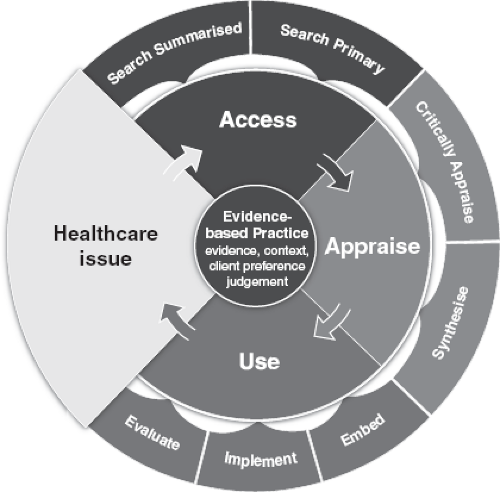

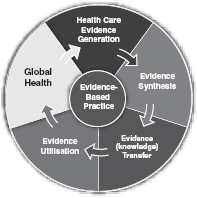

The JBI Model of Evidence-Based Healthcare adopts a pluralistic approach to the notion of evidence whereby the findings of qualitative research studies are regarded as rigorously generated evidence and other text derived from opinion, experience and expertise is acknowledged as forms of evidence when the results of research are unavailable. Based on the model, a Model of User Engagement has been developed by Jordan and Court (2009).

The Model of User Engagement was developed to demonstrate how users identify healthcare issues and pose clinical questions. The starting point is to access information – initially searching for summarized evidence.

JBI provides access to a comprehensive range of high quality evidence reviews and evidence-based information. If there is no summarized evidence available on the topic of interest, users then seek to search for primary research in the wide range of databases and journals accessible through JBI COnNECT+. Once primary papers are identified, considering research methodologies appropriate for the information sought, the recommendation is that this information be appraised prior to being relied upon. JBI RAPid provides the user with a simple framework for critically appraising any paper that is found. If multiple papers are located and further synthesis is required – or the user is a researcher wishing to undertake a systematic review – the synthesis step arises at this point. This order of approaching JBI information is also appropriate for those conducting a systematic review, as prior to undertaking a systematic review, the author will search for existing systematic reviews to ascertain the need for evidence synthesis in the chosen area.

Getting evidence into action

The systematic review of evidence and development of clinical guidelines pose significant challenges for health professionals in the practical setting. Evidence-based practice necessitates guideline development, education and review in order to achieve improved clinical outcomes. However, initiatives that endeavor to disseminate and implement clinical practice guidelines have often faced significant barriers and opposition, such as restricted access to

information, environmental factors, professional inertia and perceived degrees of usefulness or uselessness! (Hutchinson & Baker, 1999).

information, environmental factors, professional inertia and perceived degrees of usefulness or uselessness! (Hutchinson & Baker, 1999).

We would argue that the ultimate success of the evidence-based movement is dependent upon the degree to which it has an impact on health service outcomes. The uptake of evidence into practice is often slow at best and the process can be intractably difficult for a range of complex reasons. Thus, a coordinated strategy requiring appropriate skill, determination, time, money and planning is prudent for the success of any program of implementation. In Australia, the National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC, 2000) suggest that there are four elements that are desirable in order for the successful translation of research evidence into action to occur. These include good information based on research that is capable of standing up to rigorous critical appraisal and that will assist in solving practical problems; effective mechanisms and strategies for dissemination that enable health professionals and consumers to access information; physical and intellectual environments in which research is valued and uptake of research based knowledge is supported and encouraged; and interventions that demonstrably promote the uptake of knowledge and lead to behavior change.

Barriers to change

There is sometimes the assumption that in order to improve care, clinicians primarily need more concise information and user-friendly formats and systems to help them apply research findings and evidence-based guidelines. However, there is a need to address not only the information needs of health professionals and organizations but also the social and organizational factors that interfere with the application of research findings.

Regardless of profession or discipline, any plan for change requires the ability to overcome barriers to its successful implementation. These barriers may occur at different levels, regardless of whether it is organizational, staff or consumer driven, and the barriers will vary considerably for the stakeholders involved. A variety of strategies are available to overcome such barriers, and that is why it is imperative that they are identified prior to initiating any approach to facilitating change. This may be achieved through the utilization of surveys, interviews or focus groups involving all key stakeholders. The aim is to elicit their perspectives on the proposed change and to provide the stakeholders with an opportunity to feel ownership for that change.

It is important to identify potential barriers to change in the local context and there may be characteristics of the proposed change that have the potential to influence its adoption. For example, it may be necessary to pilot the change in order to assess whether or not it is compatible with current beliefs and practices of the context, as well as whether health professionals in the target group are open to the possibility of change. Small, brief tests of change can serve a valuable role in adapting change implementation strategies before widespread introduction.

Other potential external barriers to implementation of evidence-based practice might include inadequate access to information, insufficient time and money to acquire new skills, low levels of baseline skills in critical appraisal, problems with the medical and nursing hierarchy, perceived threats to medical autonomy, or lack of evidence.

If it is possible, identify those issues or problems that may make it difficult to develop evidence-based practice, and then try to identify an equal number of points that assist the process.

When a number of barriers and enablers have been identified, a useful strategy might be to discuss them with the clinical team to see if there are ways of using the enabling factors and if there are any ways around the blocking factors. In the event that those blocking factors prove to be insurmountable, the most constructive approach may be to abandon that particular project and move on to another. For example, a clinical audit might be conducted where the staff identify seven areas of concern in the prevention of falls by residents. They may be successful in changing five of those areas of concern, but it may be that management is unable to afford the costs associated with the last two. The staff will have improved the things that lay within their power and might comfortably move on to audit a new topic. Some of the most common barriers to change include:

When a number of barriers and enablers have been identified, a useful strategy might be to discuss them with the clinical team to see if there are ways of using the enabling factors and if there are any ways around the blocking factors. In the event that those blocking factors prove to be insurmountable, the most constructive approach may be to abandon that particular project and move on to another. For example, a clinical audit might be conducted where the staff identify seven areas of concern in the prevention of falls by residents. They may be successful in changing five of those areas of concern, but it may be that management is unable to afford the costs associated with the last two. The staff will have improved the things that lay within their power and might comfortably move on to audit a new topic. Some of the most common barriers to change include:

Staff information and skill deficit

A common barrier to evidence-based practice that is listed by health professionals is information and skill deficit. Lack of knowledge regarding the indications and/or contraindications, current recommendations/guidelines, or results of clinical research have the potential to cause health professionals to feel that they do not have sufficient technical training, skill or expertise to implement the change.

Psychosocial barriers

Psychosocial barriers are also common in situations where change is imminent. The feelings, attitudes, beliefs, values, and previous experiences of staff that affect clinical practice will play a considerable role during the change period.

Organizational barriers

Organizational, structural and systemic limitations may also prove to be significant barriers to change. These may include anything from outdated standing orders or accountability gaps through to the mode of resource allocation.

Resource barriers

Appropriate and effective patient care may not be achieved if the required tools, equipment, staff and other resources required to successfully achieve are not available.

Patient knowledge/skill barriers

Patients, their families or their caregivers may lack knowledge or information that is necessary for successful treatment and this may present a barrier to the proposed change.

Patient psychosocial barriers and preferences

Patients and/or their families may hold feelings, beliefs, values and experiences that interfere with successful treatment and these may present a barrier to the proposed change.

Leading and managing change

Changing healthcare practice is essentially bringing about an alteration in behavior or substituting one way of behavior for another. Some changes occur because of things around us, but most changes cannot occur effectively without being planned. Planned change is inevitably easier to manage than change which is imposed, haphazard or misunderstood. Healthcare

professionals are agents of change. They frequently endeavor to bring about changes in the behavior of clients, such as changing dependence into independence, fear into feelings of security and so forth.

professionals are agents of change. They frequently endeavor to bring about changes in the behavior of clients, such as changing dependence into independence, fear into feelings of security and so forth.

Although now something of a cliché, it is true that change is a part of our everyday lives. Is it then, a quirk of human nature that causes us to resist that which is known to be inevitable? In order to understand and work around resistance to change, it is helpful for leaders to consider resistance as a fundamental component of the change process. An understanding of why people resist and ways in which resistance is manifested can go some way towards helping healthcare professionals to lead and to smooth the path of change. It is therefore an important prerequisite to planning. Resistance is commonly viewed in two ways:

Resistance effectively hampers and blocks change

Resistance maintains order and stability

Resistance can thus be considered to be both good and bad; bad in terms of preventing or blocking something which may be advantageous or even essential; good in terms of tempering and balancing, thus constituting a brake on unplanned change.

One of the most effective ways of minimizing resistance is to actively involve people at all stages of the process. Giving people the opportunity to contribute and become part of the change personally engages them and offers them the chance to help rather than hinder. It can create a feeling of worth and recognition. As in all negotiations, the achievement of those things that we consider essential will often involve trading off those things that we consider to be less important.

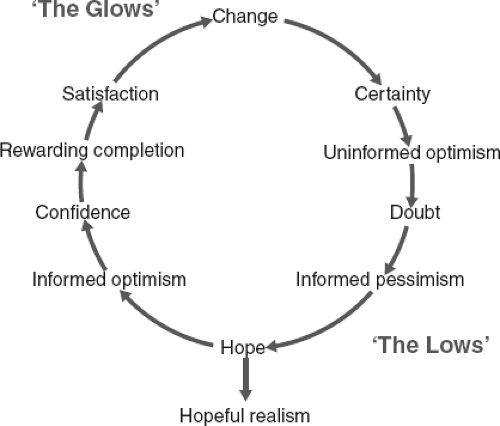

Response to change is also concerned with emotional reactions. The emotional cycle of the change process, described by Kelley and Conner (1979), relates to the feelings experienced by people participating in change. As they point out, ‘emotions of the participants fluctuate from highs to lows, and it would appear that these ‘highs’ and ‘lows’ can be identified with particular stages in the change process’. Although now somewhat dated, this work still rings true to the experience of the majority of change agents. They go on to describe this cycle in the following way:

‘Things usually start off with a ‘high’, before the participants become fully aware of what they are really letting themselves in for. This stage is referred to as uninformed optimism. The stage of informed pessimism begins when people begin to recognize the full implications, and perhaps come up against problems. This is the point at which some participants may even wish to withdraw so plans need to be laid to help them through. However, with acknowledgement, support and perhaps some re-structuring hope will begin to be generated. This is the stage of hopeful realism. Hope, and some evidence of a return for the efforts that have been made instil confidence in the venture, and is known as the stage of informed optimism. This sees the participants through to rewarding completion, which brings the glow of satisfaction’ (Figure 9).

Evidence-based healthcare and practice change

Contemporary practice is rarely based on the best available evidence; thus, implementing an evidence-based approach represents a major change in healthcare. This is recognized by many health professionals internationally.

Figure 9: ‘The Emotional Response to Change’ (Adapted from Kelley & Conner, 1979) |

Medicine

The hostility of medicine toward change, it has been suggested, has been a product of concerns regarding the potential threat to professional autonomy of individual practitioners, rationing of healthcare and the idea that evidence-based medicine presents a distorted or partial view of science and rejects much that is central to the scientific method. Although evidence-based medicine has made an enormous impact on healthcare education and policy, its translation into practice has not been universally accepted and the integration of the principles of evidence-based practice has been equally inconsistent as for other health disciplines.

Nursing

There is evidence to suggest that nurses tend to see current evidence generated through nursing research as impractical and therefore irrelevant to everyday practice. Nagy, Lumby, McKinley and Macfarlane (2001) suggest that nurses do not see themselves as possessing sufficient skills, time or organizational support to locate, appraise and implement the best available evidence. Thompson, McCaughan, Cullum, Sheldon, Mulhall and Thompson (2001) report that nurses in the UK generally do not find current guidelines, whether in printed or electronic formats, as convenient as oral information. It is likely that this is also true in Australia. Johnson and Griffiths (2001) show, however, that practice change can be promoted if practitioners are involved in processes that raise their awareness and encourage them to evaluate their own practice.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree