Gastrostomy and Jejunostomy

Gastrostomy may be performed for feeding or for decompression. The simplest open technique for creation of a gastrostomy is the Stamm procedure. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), an alternative to open gastrostomy, is also described in this chapter. Laparoscopic gastrostomy is described in Chapter 58e (which also describes the Janeway gastrostomy, a method of creating a permanent, mucosa-lined tube). Other techniques are included in the references.

After the tract has matured, a low-profile “button”-type device may be substituted for the catheter. These low-profile devices are often easier for patients and families to deal with. The exchange is made in the office or clinic and does not require anesthesia.

Jejunostomy is sometimes preferred over gastrostomy in patients in whom free gastroesophageal reflux, mental obtundation, or abnormal upper gastrointestinal motility makes aspiration of gastric feedings likely. It has been difficult to prove conclusively any advantage for this procedure over gastrostomy.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified open and percutaneous gastrostomy, and open jejunostomy, as “ESSENTIAL COMMON” procedures.

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Stomach

Fundus

Antrum

Pylorus

Lesser curvature

Greater curvature

Duodenum

Suspensory ligament of duodenum (ligament of Treitz)

Jejunum

Ileum

Cecum

Liver

Left lobe

Greater omentum

Transverse colon

Gastrocolic ligament

Gastrostomy

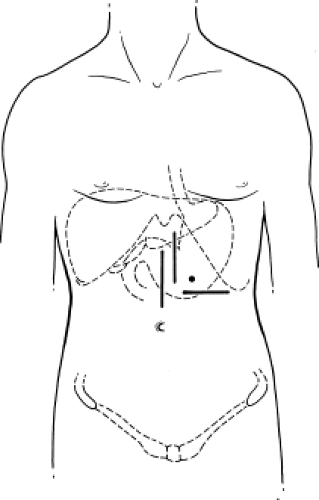

The Incision (Fig. 57.1)

Technical and Anatomic Points

The patient is positioned supine, and an upper midline, short upper left paramedian, or left transverse incision is used. The choice of incision depends on the patient’s body habitus. If an old midline scar is present, a left transverse incision provides good access through a space that is often free of adhesions.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE—GASTROSTOMY

Short upper abdominal incision

Identify and deliver stomach into wound

Two concentric purse-string sutures (2-0) silk on anterior stomach wall, leave tails long

Choose exit site on anterior abdominal wall

Create small skin incision and deliver catheter into peritoneal cavity

Incise stomach in center of purse-string sutures and insert catheter

Tie sutures, inkwelling stomach around catheter

Tack Stomach to Anterior Abdominal Wall at Four Sites Around Catheter Entry Site

Use previously placed purse-string sutures for two of these tacking stitches

Stomach should completely hide catheter from view when completed

Bring omentum into region

Close incision and anchor the catheter

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS—GASTROSTOMY

Injury to colon or even insertion of gastrostomy tube into colon

Site too close to pylorus with obstruction of pylorus if Foley catheter is used as tube

General anesthesia is preferred; however, in the cachectic, weakened patient, local anesthesia may be safer. If the procedure is to be performed using local anesthesia, use a midline incision because it requires minimal muscle manipulation. Infiltrate the skin and subcutaneous tissues with local anesthesia. As dissection progresses, inject additional local anesthesia just under the fascia to numb the peritoneum.

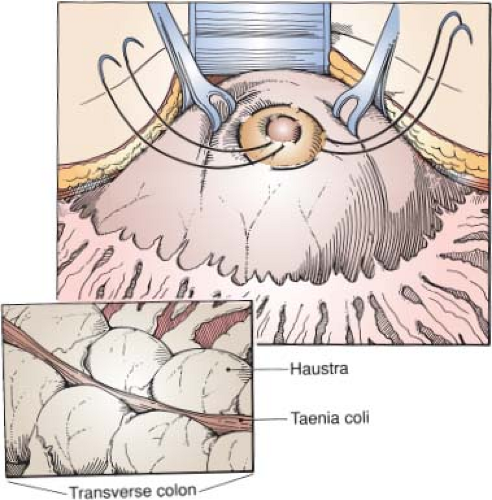

Choice of Site on Stomach Wall and Placement of Sutures (Fig. 57.2)

Technical Points

Identify the stomach with certainty by observing its thick muscular wall, absence of haustral folds and taeniae, and the vessels entering the greater and lesser curvatures. Grasp the stomach with a Babcock clamp and pull it into the wound. Choose a site well proximal to the pylorus on a mobile, accessible part of the anterior wall.

Place two concentric purse-string sutures of 2-0 silk, leaving the needles on. Begin and end one purse-string suture at the cephalad end of the incision and the other suture at the caudad end.

Anatomic Points

Remember the disposition of major organs in the upper abdomen, their attachments, and how to distinguish one from the other. On a surface projection, the stomach is located in the left hypochondriac and epigastric regions, with the pylorus just to the right of the vertebral column. The lesser curvature and the adjacent part of the stomach lie deep to the left lobe of the liver. The body of the stomach lies just deep to the parietal peritoneum of the anterior body wall. The free edge of the left lobe of the liver typically lies about halfway between the umbilicus and the xiphoid in the midline and then angles upward and to the left to pass behind the eighth costal cartilage. The greater omentum is attached to the greater curvature of the stomach. It is normally draped over the transverse colon and the numerous loops of small intestine.

The transverse colon is attached to the greater curvature of the stomach by the gastrocolic ligament (developmentally, the anterior “root” of the great omentum) and to the posterior body wall by the transverse mesocolon. It can lie anywhere in the upper abdomen, depending on the degree of redundancy of this organ and the lengths of its peritoneal attachments. Although it is classically described to be immediately inferior to the stomach and superior to the small intestine, it may be interposed between the stomach and the body wall, or conversely, it may sag inferiorly into the pelvis. To visualize small bowel, the greater omentum and often the transverse colon and transverse mesocolon must be reflected cranially.

Through the porthole of this small laparotomy incision, large bowel can be differentiated from other viscera by the presence of haustra, taenia coli, and fatty epiploic appendages.

Small bowel can be differentiated from stomach by its narrow diameter and from large bowel by the lack of the characteristics of large bowel just mentioned.

Small bowel can be differentiated from stomach by its narrow diameter and from large bowel by the lack of the characteristics of large bowel just mentioned.

Unlike the colon, stomach lacks haustra and taeniae. Although the stomach is highly distensible and somewhat mobile, it should be remembered that it is attached along its lesser curvature to the liver by the hepatogastric ligament, along its greater curvature to the transverse colon by the gastrocolic ligament, to the esophagus proximally, and to the retroperitoneal duodenum distally. Because there are neurovascular structures in the ligaments and visceral continuity proximally and distally, care should be taken when delivering the anterior wall of the stomach into the wound to ensure that it is just the distensible anterior wall, and that undue traction is not placed on the viscus wall or on the accompanying neurovascular structures.

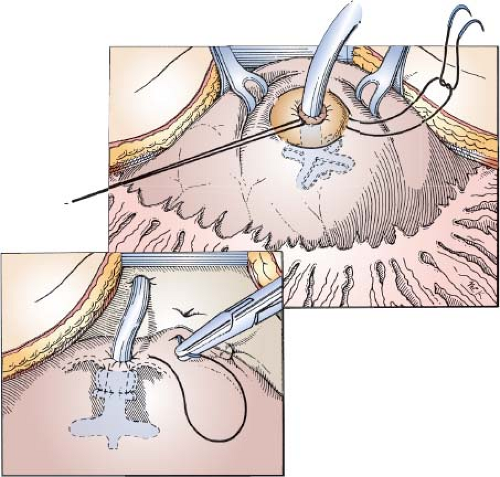

Placement of Tube (Fig. 57.3)

Technical and Anatomic Points

A large Malecot or mushroom catheter can be used. The holes in the catheter can be enlarged if desired. Choose an exit site for the catheter on the anterior abdominal wall and make a small skin incision. Deepen the hole by poking a clamp through the abdominal wall. If local anesthesia is being used, remember to anesthetize this site also.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree