1G01

Key word: Diagnosis of Appendicitis versus Acute Ileitis

Author: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Dorry L. Segev, MD, PhD

A 46-year-old woman comes to the emergency department complaining of acute right lower quadrant pain. How could appendicitis be differentiated from acute ileitis?

Colonoscopic biopsy

Development of acute or subacute pain in the right lower quadrant

Elevated white blood cell count

Presence of diarrhea

Thickened mesenteric lymph nodes on radiographic imaging

View Answer

Answer: (E) Thickened mesenteric lymph nodes on radiographic imaging

Rationale:

Acute ileitis may masquerade as acute appendicitis. Both present primarily as acute or subacute pain in the right lower quadrant. The astute clinician may be able to elicit slight differences in the history and physical examination: (1) Those patients with infectious ileitis may have colicky, intermittent pain; (2) local tenderness in the right lower quadrant may be less severe with ileitis than fulminant appendicitis; (3) while the white blood cell count is elevated in both pathologies, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate is typically higher in infectious ileitis.

In a study of 533 consecutive patients with suspected acute appendicitis or appendiceal mass by Puylaert et al., 11.4% were actually found to have bacterial enteritis of the ileocecal region on ultrasonography. Radiographic findings suggestive of ileocecal inflammation rather than acute appendicitis include enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes and symmetric mural thickening of the terminal ileum and cecum, with nonvisualization of the appendix. Responsible organisms include Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella enteritidis, and Yersinia enterocolitica. Not all patients with ileitis have diarrhea; in this study, only 36% patients eventually confirmed to have this diagnosis suffered from diarrhea. Infectious ileitis is typically a benign and self-limiting condition—thus effort should be made to exclude it as a possible mimicker of appendicitis before proceeding to the operating room for an appendectomy. Antibiotic treatment is typically not necessary, nor is operative resection.

References:

Melton GB, Li R, Duncan MD, et al. Acute appendicitis. In: Cameron JL, Cameron AM, eds. Current Surgical Therapy. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2011:219-223.

Puylaert JB, Van der Zant FM, Mutsaers JAEM. Infectious ileocecitis caused by Yersinia, Campylobacter and Salmonella: clinical, radiologic and US findings. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:3-9.

Puylaert JB, Vermeijden RJ, van der Werf SD, et al. Incidence and sonographic diagnosis of bacterial ileocaecitis masquerading as appendicitis. Lancet. 1989;2(8654):84-86.

1G02

Key word: Treatment of Recent 4-cm Pancreatic Pseudocyst

Author: Justin B. Maxhimer, MD

Editors: Timothy M. Pawlik, MD, MPH, PhD, and Matthew J. Weiss, MD

A 60-year-old man who suffers from chronic alcoholism is admitted to the hospital with an episode of acute pancreatitis. He suffered similar episodes in the past—all of which have resolved without complications. On laboratory studies, he is found to have an elevated serum amylase level. A computed tomography (CT) scan is performed which demonstrates a 4-cm pancreatic pseudocyst. What would be the best subsequent treatment?

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Observation and serial CT scans

Percutaneous drainage

Puestow procedure

Simple aspiration

View Answer

Answer: (B) Observation and serial CT scans

Rationale:

Pseudocysts are fluid collections, usually inflammatory in origin, that arise in or in close proximity to the pancreas. By definition, pseudocysts lack an epithelial lining. Most pseudocysts are seen in the context of either acute or chronic pancreatitis. A small proportion of pseudocysts are post-traumatic. In children, trauma is the most common etiology of pancreatic pseudocysts. Pseudocysts developing from acute pancreatitis usually are extrapancreatic, loculated collections of amylaserich fluid that develops within 2 weeks of the onset of the attack. It probably results from either the disruption of a pancreatic duct or from leakage from the inflamed surface of the gland. A ductal communication is not typically demonstrable. Most such peripancreatic “acute fluid collections” resolve spontaneously unless they contain a large amount of necrotic material or become infected. Some persist and develop a wall of fibrous granulation tissue.

The pseudocysts of chronic pancreatitis may result from one of two pathogenic processes. First, a necrotic collection may develop as a complication of an attack of acute-on-chronic pancreatitis. Secondly, a retention collection may occur as a result of blockage of a major branch of the pancreatic duct by localized fibrosis, a calculus, or a protein plug, leading to the rupture of the corresponding acini. O’Malley et al. noted that pseudocysts of more than 4 cm resolved spontaneously at a mean of 3 months after diagnosis although, in one case, resolution did not occur until 28 months. Maringhini et al. found that within 1 year after diagnosis, 65% of acute pseudocysts resolved. Pseudocysts of less than 5 cm in size were more likely to resolve than larger ones. Gouyon et al. observed a pseudocyst resolution rate of 26% in patients with chronic alcoholic pancreatitis. The median time to regression was 29 weeks (range 2 to 143 weeks) and the independent

predictive factor of pseudocyst resolution or an asymptomatic course was a size of less than 4 cm. Size was also a major factor predicting pseudocyst resolution in the Aranha et al. series. The mean diameter of cystic lesions that resolved was 4 ± 1 cm as compared to a diameter of 9 ± 1 cm in those cysts that did not resolve. Only 4 of 26 pseudocysts greater than 6 cm in diameter at initial examination resolved. Several more studies also confirmed that cysts less than 4 cm in diameter can resolve spontaneously.

Reference:

Andrén-Sandberg A, Dervenis C. Pancreatic pseudocysts in the 21st century. Part I: classification, pathophysiology, anatomic considerations and treatment. JOP. 2004;5:8-24.

1G03

Key word: Best Test of Successful Treatment of H. Pylori

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editors: Thomas H. Magnuson, MD, and Kenzo Hirose, MD, FACS

A 63-year-old man presents with a “gnawing” upper abdominal pain. He reports that he was diagnosed with a gastric ulcer years ago. Which of the following tests is most sensitive in diagnosing the patient with infection with Helicobacter pylori?

Histologic examination of endoscopic antral biopsies

Serum antibodies to

H. pylori

Upper GI radiographic series

Urea breath test

Urease test of endoscopic antral biopsies

View Answer

Answer: (A) Histologic examination of endoscopic antral biopsies

Rationale:

H. pylori has a strong association with the development of peptic ulcer disease. Treatment with bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline is associated with eradication of H. pylori and peptic ulcers.

The gold standard of testing for diagnosis of H. pylori is histologic examination of endoscopic antral biopsies for presence of H. pylori, with 92% sensitivity and 100% specificity.

The urease test requires placing the endoscopic biopsies into a gel matrix and looking for color change. While the turnaround time for the urease test using endoscopic antral biopsies is quicker than histology, it has 90% sensitivity and 100% specificity.

The urea breath test, also known as the 13C- or 14C-urea breath test, while noninvasive, is limited to 90% sensitivity. All of the aforementioned tests can give false negatives if the patient has undergone a recent short course of antibiotics.

ELISA testing for serum antibodies to H. pylori has 87% sensitivity and 85% specificity, as antibodies may persist for up to 1 year after eradication.

The upper GI radiographic series is useful for diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease by visualization of ulceration, not infection with H. Pylori. However, it has 54% sensitivity and 91% specificity. Therefore, endoscopy, providing the ability to take mucosal biopsies, is also the gold standard for diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease.

References:

Mulholland MW. Gastroduodenal ulceration. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Yamada T. Acid-peptic disorders and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Powell DW, Owyang C, Silverstein FE, Hasler WL, Traber PG, Tierney WM, eds. Handbook of Gastroenterology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:265-280.

1G04

Key word: Treatment of Liver Hemobilia

Author: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Richard D. Schulick, MD, MBA, FACS

A 72-year-old man undergoes percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) and percutaneous biliary drainage (PBD) for obstructive jaundice secondary to pancreatic cancer. Following the PTC/PBD, he develops melena and bright red blood is seen in the biliary drain. Laboratory work reveals a drop in hematocrit and increase in his liver function tests. What is the definitive treatment for this change in his condition?

Biliary stent placement

Endoscopic epinephrine injection at the site of the bleeding vessel

Hepatic resection

Transarterial embolization

Whipple procedure

View Answer

Answer: (D) Transarterial embolization

Rationale:

Hemobilia is defined as bleeding into the bile duct resulting from communication between a blood vessel and the duct. Clinical manifestations include melena and/or hematemesis, right upper quadrant pain, anemia, transient worsening of liver function tests, and jaundice. Shock may ensue if the bleeding is profuse. The site of communication between the duct and vessel may be either intra- or extrahepatic.

The most common causes of hemobilia are iatrogenic, accounting for two-thirds of cases, with percutaneous liver procedures accounting for 38%. Other than PTC/PBD (incidence 2% to 10%), liver biopsy (incidence <1%) and hepatectomy may result in hemobilia. Other causes of hemobilia include trauma, liver abscesses, mycotic aneurysms, vascular malformations, tumors, and hemorrhagic cholecystitis. Since frank bleeding is rare, the diagnosis may be unclear for months; alternately, a patient may present with melena or hematemesis. Brisk bleeding may be difficult to differentiate from that originating from the stomach or duodenum. Bleeding at a slow rate may clot within the biliary tree leading to obstructive jaundice.

Currently, the standard of care for treatment of hemobilia secondary to erosion into a hepatic artery branch is to attempt transarterial embolization. Angiography detects over 90% of causes of major hemobilia, and selective embolization is successful in 80% to 100% of the time. If hemobilia is secondary to erosion into a portal vein branch, upsizing the PBD may be sufficient to prevent bleeding by inducing tamponade. Surgery is indicated if embolization fails or in the settings of hemorrhagic cholecystitis or hepatic necrosis. Surgical treatment entails selective ligation of the bleeding artery, which may require a segmental liver resection, or removal of the root cause (i.e., vascular malformation, mycotic aneurysm, etc.) Mortality from hemobilia currently is <5%.

References:

Dousset B, Sauvanet A, Bardou M, et al. Selective surgical indications for iatrogenic hemobilia. Surgery. 1997;121(1): 37-41.

Schlinkert RT, Kelly KA. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Souba WW, Fink MP, Jurkovich GJ, Kaiser LR, Pearce WH, Pemberton JH, Soper NJ, eds. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. New York, NY: WebMD; 2004:321.

Srivastava DN, Sharma S, Pal S, et al. Transcatheter arterial embolization in the management of hemobilia. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31(4):439-448.

Wolf DS, Wasan SM, Merhav H, et al. Hemobilia in a patient with protein S deficiency after laparoscopic cholecystectomy that caused acute pancreatitis: Successful endoscopic management. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(1):163-166.

1G05

Key word: Treatment of Rectal Bleeding after Hemorrhoid Banding

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Susan L. Gearhart, MD

A 36-year-old woman underwent banding for an internal hemorrhoid 1 week ago. She contacts your office complaining of a small amount of blood on toilet paper after defecation, but denies pain or fever. The next step in her management is:

Direct the patient to the emergency room

Instruct the patient to apply cold compresses to the perineum

Instruct the patient to take fiber supplementation and increase fluid intake

Prescribe nifedipine ointment BID to the perianal region

Tell the patient there is nothing to do

View Answer

Answer: (C) Instruct the patient to take fiber supplementation and increase fluid intake

Rationale:

Five to ten days after banding or surgery for internal hemorrhoids, it is common for patients to experience minimal bleeding due to sloughing of eschar. It is important to reassure patients that this occurs frequently and should not cause alarm. Sitz baths can be helpful in easing pain and inflammation, while fiber supplementation can help soften stool, thereby preventing local trauma to the surgical site. Patients should be encouraged to maintain adequate fluid intake. Aspirin-containing compounds should be avoided, as they may precipitate further bleeding. Nifedipine ointment is used in the treatment of fissures, which is unlikely in this patient as she denies presence of pain.

Only in the event of significant bleeding is further intervention warranted. Should this occur, patients should undergo examination under anesthesia with ligation of the source of the bleeding.

Reference:

Kodner IJ. Anal procedures for benign disease. In: Souba WW, ed. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice. Decker Intellecutal Properties, 2009. Accessed August 27, 2013. Online Edition.

1G06

Key word: Treatment of Colon Cancer Metastases to the Liver

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Michael A. Choti, MD, MBA

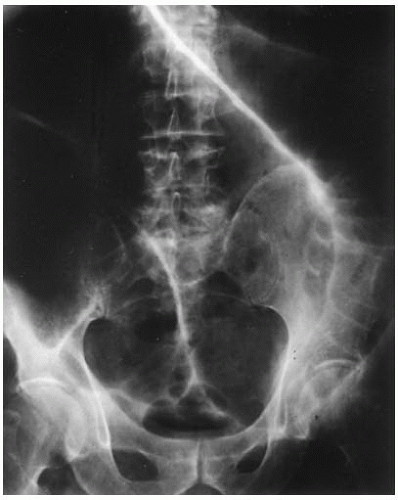

A 56-year-old man 2 years status post left colectomy for stage IIA colon cancer is now found to have rising carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and two new lesions in the liver on follow-up CT scan (see scans below). There is no evidence of extrahepatic disease. How do you manage this patient?

Extended left hepatectomy

Orthotopic liver transplantation

Palliative chemotherapy

Radiofrequency ablation of the two tumors

Y-90 intra-arterial therapy

View Answer

Answer: (A) Extended left hepatectomy

Rationale:

The most common site of distant metastases from colorectal cancer is the liver. A 5-year survival rate of approximately 50% is seen in patients who undergo resection for hepatic metastases. However, not all patients are candidates for surgical resection. Resectabilty is no longer defined by size, number, or location of metastases within the liver. Rather, a patient is considered resectable if all disease can be resected with negative margins (R0) and a sufficient healthy remnant liver remains with adequate vascular inflow, outflow, and biliary drainage.

In this case, the patient has two bilobar lesions, one 4-cm tumor in the left liver and a second 1.5-cm tumor in the anterior right liver (segment 8). The disease appears resectable. Extended left hepatectomy or two separate resections (left partial or complete hepatectomy and wedge resection of the right-sided lesion) could be performed. Radiofrequency ablation or other ablative approaches should only be reserved in cases where the disease is unresectable. Similarly, intraarterial therapy is generally only considered in selective cases of unresectable disease. In most cases such as this, chemotherapy is recommended in the perioperative period. It can be administered adjuvantly following resection or it can be offered for a short duration as neoadjuvant therapy.

Reference:

Choti MA, Sitzmann JV, Tiburi MF, et al. Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2002;235(6):759-766.

Pawlik TM, Choti MA. Surgical therapy for colorectal metastases to the liver. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(8):1057-1077.

1G07

Key word: Treatment of Duodenal Obstruction in Crohn Disease

Authors: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH, and Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Mark D. Duncan, MD, FACS

Workup for vomiting in a 46-year-old woman with Crohn disease reveals a stricture in the second portion of the duodenum. What is the best surgical management of this problem?

Heineke-Mikulicz strictureplasty

Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure)

Resection of the affected segment with primary anastomosis

Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy

Side-to-side retrocolic gastrojejunostomy

View Answer

Answer: (A) Heineke-Mikulicz strictureplasty

Rationale:

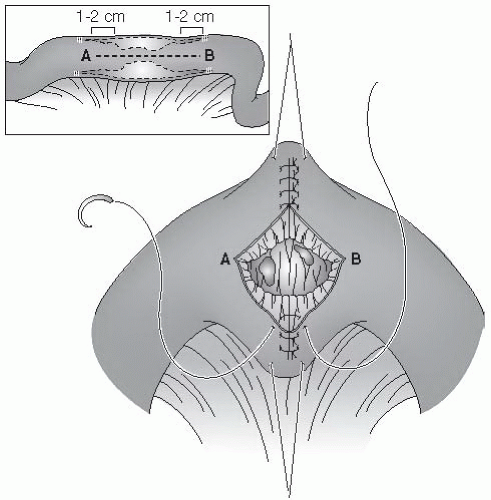

Involvement of the duodenum in Crohn disease is usually limited to stricture formation, ulceration, and edema, as opposed to fistulization or abscess formation. Therefore, strictureplasty and bypass operations may be used rather than resection. Most strictures are limited to the first or second portion of the duodenum, and may be managed via a strictureplasty in the manner of Heineke-Mikulicz. This technique calls for a longitudinal incision on the antimesenteric border of the stricture, followed by transverse closure. Longer strictures in the duodenum should be managed with side-to-side retrocolic gastrojejunostomy. However, due to the ulcerogenic nature of this procedure, a truncal vagotomy, or preferably a highly selective vagotomy, should be performed at the same time as the gastrojejunostomy. Disease affecting the distal duodenum, but sparing the first two portions of the duodenum, are amenable to bypass via Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy. A vagotomy is not necessary for this procedure.

References:

Michelassi F, Stein SL. Crohn disease. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch R, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

1G08

Key word: Diagnosis of Caustic Ingestion

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Nicole M. Chandler, MD

A 38-year-old male presents to the emergency department after attempted suicide via ingestion of oven cleaner. Upon rigid esophagoscopy, you observe erythematous, friable, mucosa with superficial, noncircumferential white ulcerations in the mid-esophagus. What degree of injury is this lesion?

Grade I

Grade IIA

Grade IIB

Grade III

Grade IV

View Answer

Answer: (B) Grade IIA

Rationale:

Classically, there is a bimodal distribution of patients presenting with caustic injuries to the oropharynx and esophagus; children who ingest caustic materials accidentally, and adults who ingest them during a suicide attempt.

Patients with significant caustic ingestion may present with oropharyngeal and/or chest pain, dysphagia, and drooling. Hoarseness and stridor are associated with laryngeal and epiglottal injuries and may necessitate orotracheal intubation for airway protection. Dysphagia and hematemesis are associated with esophageal injury, with retrosternal and epigastric pain associated with full-thickness injury and/or gastric injury. Peritoneal signs, cervical emphysema, and back pain are associated with esophageal perforation. However, in 37% of patients found to have esophageal damage, there are no signs of oropharyngeal burns.

Therapy should begin as soon as diagnosis is suspected. Attempts to dilute or neutralize caustic agents are contrain-dicated, in part because induction of vomiting will increase exposure to the agent. Similarly, blind passage of nasogastric tubes or nasopharyngeal intubation is contraindicated due to risk of perforation and further injury.

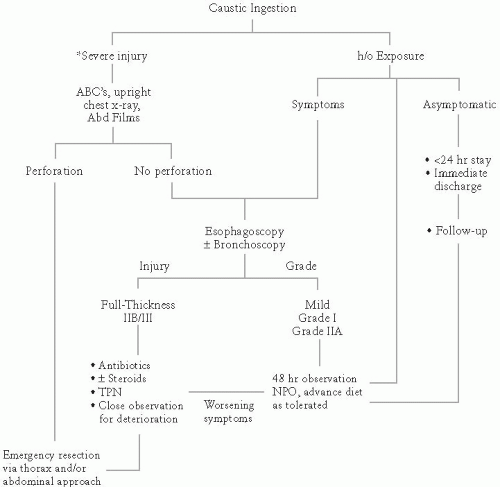

Treatment begins with airway assessment and stabilization, and is followed by fluid resuscitation. Plain radiographs of the chest and abdomen can reveal indications for emergent exploration, such as pneumoperitoneum, pneumomediastinum, and pleural effusions, which are all consistent with esophageal perforation.

If there is no indication for immediate surgical intervention, patients should undergo endoscopy, preferably within 12 to 24 hours of the toxic exposure. Delay in endoscopy can increase the likelihood of iatrogenic perforation as wounds begin to remodel and soften by postinjury day 2. All symptomatic patients should undergo endoscopy. Endoscopy should not be performed past the level of the greatest injury, to minimize the risk of iatrogenic perforation.

Degrees of esophageal Burns:

Grade I: Superficial mucosal injury characterized by erythema and mucosal edema

Grade IIA: As above PLUS partial-thickness noncircumferential ulceration characterized by white, patchy ulcers, mucosal sloughing, and pseudomembranes

Grade IIB: As above PLUS deep or circumferential ulceration

Grade IIIA: As above PLUS transmural injury characterized by full-thickness scattered necrosis, dark ulcers with eschar formation

Grade IIIB: Extensive areas of necrosis

Between 70% and 100% of Grade IIB and 100% of Grade III injuries result in strictures.

References:

Crookes PF. Esophageal caustic injury. In: Yeo CJ, ed. Shackelford’s Surgery of the Alimentary tract. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc.; 2013:486-493.

Rascoe PA, Kucharczuk JC, Kaiser L. Esophagus: tumors and injury. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

1G09

Key word: Etiology of Hematogenous Metastases to the Small Bowel

Author: Kelly Olino, MD

Editor: Mark D. Duncan, MD, FACS

A 40-year-old male former Australian lifeguard with a history of melanoma presents to the emergency department with a month-long history of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. What is the most likely cause for his symptoms?

Colonic obstruction

Diverticulitis

Duodenal adenocarcinoma

Gastroenteritis

Intussusception of the small bowel

View Answer

Answer: (E) Intussusception of the small bowel

Rationale:

The most common extraintestinal cancer to metastasize to the small bowel is melanoma, followed by bronchogenic carcinoma and breast cancer. The route of hematologic dissemination is via the arterial blood supply from the superior mesenteric artery. In a Memorial Sloan-Kettering review of metastatic melanoma to the gastrointestinal tract, the most common presenting symptoms were intermittent small bowel obstruction, due to intussusception, and gastrointestinal bleeding-induced anemia. Although only a minority of patients was clinically diagnosed with small bowel metastases, autopsies revealed up to 50% of patients with disseminated melanoma had gastrointestinal metastases. It is, therefore, important in patients with a history of melanoma to work up all cases of abdominal pain for metastatic disease. Gastroenteritis or diverticulitis would not fit the time course stated. Duodenal or colonic adenocarcinoma is possible but unlikely given the patient’s age.

References:

Agrawal S, Yao TJ, Coit DG. Surgery for melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6: 336-344.

Gill SS, Heuman DM, Mihas AA. Small intestinal neoplasms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:267-282.

1G10

Key word: Treatment of C. difficile in Pregnancy

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Nicole M. Chandler, MD

A 22-week pregnant, 31-year-old woman received 7 days of ampicillin for a urinary tract infection. The patient developed diarrhea on day 5 of therapy, and stool is positive for Clostridium difficile toxin. How would you treat the patient?

Clindamycin 300-mg PO QID for 10 days

Do nothing, this is usually self-limiting

Metronidazole 500-mg PO QID for 10 days

Vancomycin 500-mg PO QID for 10 days

Vancomycin 500-mg PR QID for 10 to 14 days

View Answer

Answer: (D) Vancomycin 500-mg PO QID for 10 days

Rationale:

Diarrhea develops in 5% to 20% of patients taking antibiotics. One in approximately 1,000 of these cases is due to C. difficile. Most episodes of antibiotic-induced diarrhea occur after ampicillin, clindamycin, or third-generation cephalosporin use, and may present up to 6 weeks after cessation of antibiotics. In asymptomatic patients, the disease may be self-limiting and does not necessarily require antibiotic treatment.

Treatment of C. difficile gastrointestinal infection is with antibiotics when the disease is symptomatic. Metronidazole, 250-mg to 500-mg PO QID for 10 days is the treatment of choice for most patients. However, in patients who are pregnant or lactating, oral vancomycin 500-mg PO QID for 10 days is preferred to metronidazole. Orally and rectally administered vancomycin is not absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, it does not become systemic, and the risk of exposure to the fetus or accumulation in breast milk is minimal.

Other indications for use of oral vancomycin in lieu of metronidazole are in the setting of failure of metronidazole therapy after 3 to 5 days of use, and metronidazole intolerance. Metronidazole-resistant isolates of C. difficile have been identified; thus vancomycin therapy should be used for refractory or recurrent cases.

While clindamycin 300-mg PO QID for 10 days is effective and safe to use in pregnant patients based on animal studies, it is more likely to cause this disease than to treat it.

References:

Bartlett JG. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(5):334-339.

Christou NV. Antibiotics. In: Souba WW, ed. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice. Decker Intellecutal Properties, 2010. Accessed August 27, 2013. Online Edition.

Garey KW, Jiang Z-D, Yadav Y, et al. Peripartum Clostridium difficile infection: Case series and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:332-337.

Green SM, ed. Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia. 2005 classic shirt-pocket edition, Lompoc, CA: Tarascon; 2005:33-35.

1G11

Key word: Treatment of Anal Fissure with Rectal Bleeding

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editors: Christopher L. Wolfgang, MD, PhD, and Matthew J. Weiss, MD

A 43-year-old man presents to your clinic complaining of intermittent blood spotting on toilet paper for 2 weeks. Anoscopy reveals a 1-cm split in the anoderm posteriorly on the midline distal to the dentate line, lacking any hypertrophy or visible muscle fibers. What is the optimal management?

Bisacodyl suppositories

Initiate stool softeners

Lateral internal anal sphincterotomy

Observation only

Resection of affected tissue

View Answer

Answer: (B) Initiate stool softeners

Rationale:

Anal fissures result from laceration of the anoderm by large hard stools in combination with inability to properly relax the anal sphincter. Fissures are diagnosed via anoscopy, and are usually located midline posteriorly or anteriorly.

Acute anal fissures, existing less than 4 weeks, are best managed nonoperatively with stool softeners, increased dietary water intake, sitz baths, and application of topical anesthetic ointments. Suppositories are to be avoided as they irritate the fissure.

On the other hand, chronic anal fissures, of greater than 4 weeks duration, are characterized by the presence of a sentinel skin tag with an adjacent hypertrophied anal papilla. Often, internal anal sphincter fibers are visible at the base of chronic anal fissures. Chronic fissures respond poorly to conservative management. Operative management entails lateral internal anal sphincterotomy, with a cure rate of up to 98%. Recent effective therapy has also been obtained with local injection of botulinum toxin (Botox).

Reference:

Kodner IJ. Anal procedures for benign disease. In: Souba WW, ed. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice. Decker Intellecutal Properties, 2009. Accessed August 27, 2013. Online Edition.

1G12

Key word: Treatment of Esophageal Perforation

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editors: Stephen M. Cattaneo II, MD, and Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

A 54-year-old alcoholic man presents to the emergency department with severe substernal and epigastric pain after vomiting while drinking earlier that evening. Gastrografin esophagogram shows perforation of the distal esophagus with drainage into the left pleural space. What is the most appropriate treatment?

Emergent primary repair via left thoracotomy

Esophageal stent placement

Esophagectomy and delayed reconstruction with interposition graft

Esophagostomy and placement of a feeding jejunostomy tube

Nonoperative management with total parenteral nutrition and nasogastric decompression

View Answer

Answer: (A) Emergent primary repair via left thoracotomy

Rationale:

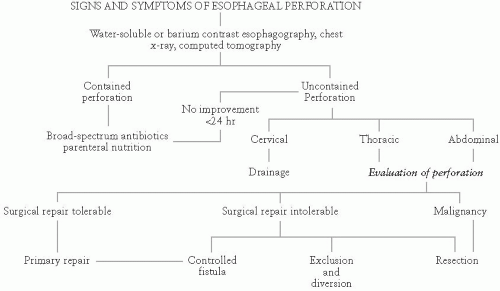

Causes of esophageal perforation, by incidence, are medical instrumentation (43%), trauma (19%), spontaneous (e.g., vomiting) (16%), surgical (8%), foreign body (7%), tumor (4%), and others (3%). Perforation due to diagnostic endoscopy usually occurs at or just proximal to a pathologic process. Other locations where instrumentation may cause perforation include Killian triangle, formed by the inferior constrictors and cricopharyngeus muscle, and other sites of anatomic narrowing including at the level of the aortic arch and just proximal to esophagogastric junction. Causes of spontaneous rupture are related to rapidly increased intraluminal pressure and include vomiting, coughing, seizures, weight lifting, and childbirth, among others. Location of spontaneous rupture is usually either at the distal esophagus on the left, or just above the level of the esophagogastric junction. Seventy percent of perforations are on the left, 20% on the right, and 10% bilateral.

The clinical presentation of esophageal perforations is dependent upon location of the tear and degree of associated contamination. Cervical perforation results in cervical pain and tenderness, pain and difficulty on swallowing, and sometimes crepitus. Fevers develop early, and pleural effusions may develop up to 24 hours after the injury. Patients who experience spontaneous rupture are usually middle-aged males with a recent history of vomiting. These patients present with substernal and epigastric pain, pleural effusions, and mediastinal emphysema. As these patients often appear late relative to the timing of their perforation, they often have fevers and tachycardia and early signs of sepsis and fare poorly.

The key to successful patient management is suspicion and early diagnosis. After history and physical examination, posterior-anterior and lateral chest x-rays should be obtained. Chest films reveal pneumothorax (77%), mediastinal emphysema (40%), or no abnormalities (10%). Following suspicious chest x-ray, a contrast espohagogram should be performed (first using water-based contrast such as gastrografin, and then repeated with thin barium if no leak is seen initially). Leaks are seen on esophagogram in 90% of patients with thoracic esophageal perforation, but this modality is less sensitive for cervical leaks. CT may aid in identifying cases where an esophagogram is equivocal, but is seldom diagnostic alone.

Principals underlying treatment are preventing further contamination, debriding infected and necrotic tissue, providing appropriate nutritional support, and restoring the continuity of the gastrointestinal tract. The surgeon must also establish whether the perforation occurred in the setting of a normal esophagus or secondary to a tumor, stricture, or motility dysfunction. Initial management includes NPO status, intravenous fluid resuscitation, careful placement of a nasogastric tube put to sump-suction, and administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Nonoperative management is a viable option for patients with small intramural or transmural perforations contained in the mediastinum with good drainage back into the esophagus, no distal obstruction or malignancy, and no signs of sepsis. Patients meeting these criteria should be maintained NPO, with TPN and H2 blockers. Re-evaluation is via esophagogram after 7 to 14 days. Endoscopic stenting may be a viable option in similar patients.

Repair of esophageal perforation occurring within 24 hours is associated with a 92% survival rate. A left thoracotomy is performed for ruptures of the distal third of the esophagus, with debridement of devitalized tissues, primary repair of the perforation, and reinforcement with tissue buttress such as parietal pleura or an intercostal muscle flap. Mediastinal debridement and drainage is necessary. Intra-abdominal esophageal perforations are repaired through a midline abdominal incision. In the setting of a highly unstable patient with a massively contaminated field, diversion by esophagostomy or esophageal stenting, with tube thoracostomy drainage of the chest may be the best option.

In the event of delayed diagnosis (>24 hours), esophagectomy with delayed reconstruction has a more favorable outcome than primary repair (13% mortality vs. 68%).

References:

Rascoe PA, Kucharczuk JC, Kaiser L. Esophagus: Tumors and injury. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Wright CD. Management of esophageal perforation. In: Sugarbaker DJ, Bueno R, Krasna MJ, Mentzer SJ, Zellos L, eds. Adult Chest Surgery. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2009:353-360.

1G13

Key word: Arterial Supply for a Gastric Tube

Author: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editors: Timothy M. Pawlik, MD, MPH, PhD, and Matthew J. Weiss, MD

A 60-year-old man with a long history of smoking and heavy alcohol use undergoes a transhiatal esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. He does well and is discharged from the intensive care unit on the second postoperative day. However, on the third day he develops a fever and malaise. A chest and neck CT scan demonstrates severe inflammation as indicated by stranding around, and wall thickening of, the gastric conduit but no intramural air. Which vascular supply to the stomach may have been compromised during the transhiatal esophagectomy?

Gastroduodenal artery

Left gastric artery

Left gastroepiploic artery

Right gastroepiploic artery

Short gastric arteries

View Answer

Answer: (D) Right gastroepiploic artery

Rationale:

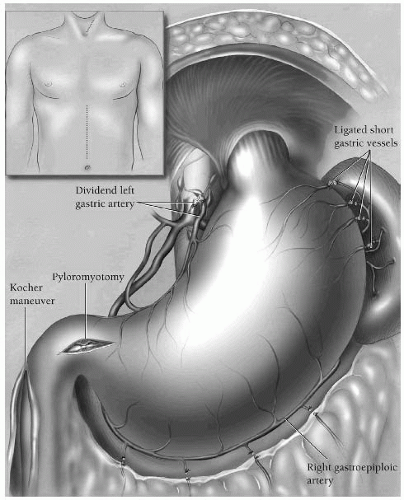

The stomach is extremely well vascularized, deriving blood from the left and right gastric arteries, the left and right gastroepiploic and the short gastric arteries. The anterior wall of the stomach is supplied primarily by the right gastroepiploic artery, which is a terminal branch of the gastroduodenal artery, which branches off the common hepatic artery. The right gastroepiploic artery supplies the greater curvature of the stomach, along with the left gastroepiploic, which derives from the splenic artery. The right and left gastric arteries supply the lesser curvature. The right gastric artery branches off the proper hepatic artery, while the left gastric is one of the three primary divisions of the celiac trunk. The short gastric arteries also supply the greater curvature, stemming from the splenic artery.

A transhiatal esophagectomy, however, requires mobilization of the stomach for creation of the conduit and ligation of many vessels. This patient is suffering from necrosis of his esophageal replacement conduit. During dissection, all of the short gastric arteries are ligated, as are the left gastroepiploic and left gastric arteries. Care must be taken during dissection along the inferior aspect of the stomach within the greater omentum where the left and right gastroepiploic meet so as not to injure the right-sided vessel. The right gastric and right gastroepiploic arteries are responsible for supplying the gastric conduit once it is mobilized into the neck. Another cause for conduit necrosis can be division of the left gastroepiploic vessels too close to the stomach or excessive traction on the stomach.

References:

Netter FH. Atlas of Human Anatomy. 2nd ed. Plates 282-283. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; 1997.

Orringer MB. Transhiatal esophagectomy without thoractomy. In: Fischer JE, Bland KI, eds. Mastery of Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:773-774.

1G14

Key word: Diagnosis of Colonic Pseudoobstruction

Author: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editors: Christopher L. Wolfgang, MD, PhD, and Matthew J. Weiss, MD

You are called by the intensive care unit (ICU) regarding a 45-year-old man intubated for ARDS for the past 3 weeks. Over the past 48 hours, he has developed increased abdominal distension. His last bowel movement was 4 days ago, and the ICU staff has attempted multiple enemas without result. An abdominal plain film has revealed diffuse dilation of the colon consistent with ileus, without an identifiable transition point. Your physical examination demonstrates a critically ill man with a rotund abdomen. There is no fluid wave or shifting dullness, just diffuse tympany. There is no stool in the rectal vault. How should you proceed with treatment?

Endoscopic decompression

Manual disimpaction

Nasogastric tube decompression and serial examinations

Neostigmine

Therapeutic enteroclysis

View Answer

Answer: (C) Nasogastric tube decompression and serial examinations

Rationale:

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction, also known as Ogilvie syndrome, arises spontaneously in critically ill patients. In spite of signs and symptoms of bowel obstruction, there is no actual mechanical obstruction. Signs and symptoms mimic those of true mechanical obstruction: Distension, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and tenderness to palpation. Colonic distension is often localized to the right side.

Although the etiology is incompletely understood, the condition may derive from the dysregulation of the autonomic nervous syndrome combined with pharmacologic or metabolic factors. The risk of spontaneous colonic perforation is 3%, with an ensuing mortality of up to 50%.

The surgical consultant must rule out true obstruction in evaluating potential Ogilvie syndrome. The cecum should be carefully evaluated for size, and concern should be raised if the acute distention results in a cecal diameter greater than 12 cm. Most cases respond to conservative treatment within 3 days, including a nasogastric tube, promotility agents, and enemas. The surgeon must monitor the patient closely for untoward changes with serial abdominal examinations. Should the problem persist, 2.5 mg of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor neostigmine may be administered. This agent can have significant side effects such as bradycardia, bronchial secretions, asthma exacerbation, salivation, and of course gastrointestinal output. If still unresolved, endoscopic decompression should be attempted. Surgical treatment is indicated

only in the event of refractory pseudo-obstruction or in the case of spontaneous perforation.

References:

Mehta R, John A, Nair P, et al. Factors predicting successful outcome following neostigmine therapy in acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: A prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(2):459-461.

Soybel DL, Landman WB. Ileus and bowel obstruction. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Tack J. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome). Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9(4):361-368.

Wick EC. Colonic and rectal anatomy and physiology. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

1G15

Key word: Treatment of Gallstone Ileus

Author: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editors: Thomas H. Magnuson, MD, and Kenzo Hirose, MD, FACS

An 88-year-old woman presents from a nursing home with altered mental status and abdominal distension. She has a history of gallstones and has never had abdominal surgery. On examination, she is febrile and tachycardic and has a distended, tender abdomen that is tympanitic to percussion. A plain abdominal film demonstrates dilated loops of small bowel with air in the biliary tree. What is your proposed management?

A trial of nasogastric tube decompression, IV fluids, bowel rest

ERCP and stent placement

Exploratory laparotomy

Family meeting and likely comfort care measures only given extremely poor prognosis

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

View Answer

Answer: (C) Exploratory laparotomy

Rationale:

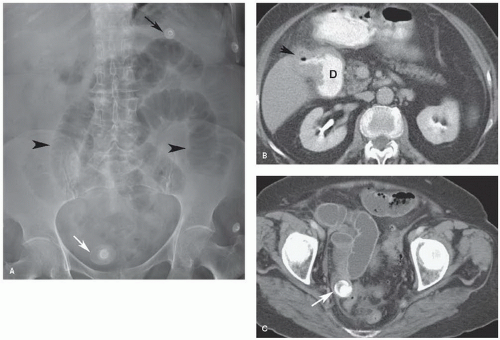

This woman has likely developed gallstone ileus and warrants surgical exploration. This condition develops most often in the elderly who have a history of gallstones and is characterized by the triad of small bowel obstruction, pneumobilia, and an ectopic gallstone. A laminated, calcified mass is visualized on CT scan, and occasionally on plain film. The gallstone may travel through the common duct, or via a cholecystoenteric fistula (a choleduodenal fistula was found in 68% of patients in one study). The terminal ileum at the ileocecal valve is the most common site of obstruction.

Spontaneous passage of the stone occurs rarely (7%) so an emergent laparotomy for stone removal is warranted. An accompanying cholecystectomy and resection of the fistula is controversial, as cholangitis may result from passage of intestinal contents into the biliary tree. Fortunately, gallstone ileus is a rare complication, presenting in fewer than 6 of 1,000 cases of cholelithiasis and is associated with less than 3% of intestinal obstruction.

References:

Ishikura H, Sakata A, Kimua S, et al. Gallstone ileus of the colon. Surgery. 2005;138(3):540-542.

Soybel DI, Landman WB. Ileus and bowel obstruction. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

1G16

Key word: Treatment of Retained Common Bile Duct Stone after T-tube

Author: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Michael A. Choti, MD, MBA

A 54-year-old woman comes to clinic 3 weeks after undergoing a common bile duct exploration for biliary stones refractory to endoscopic management. She was left with a T-tube in place, which has been reliably draining bile until 2 days ago. Over the past 48 hours, she has noted increased right upper quadrant pain that is similar to her preoperative pain. You order a tube cholangiogram, which demonstrates a retained stone lodged in the common bile duct. How should you proceed?

Admit to the hospital, make NPO with IVF, provide analgesia and observe

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

Laparoscopic stone extraction

Remove the T-tube and perform immediate choledochoscopy

Repeat open common bile duct exploration

View Answer

Answer: (D) Remove the T-tube and perform immediate choledochoscopy

Rationale:

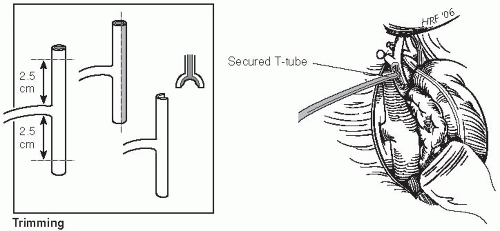

The common bile duct exploration assists in gallstone removal, particularly when ERCP is not feasible. Postoperatively, the surgeon may place a T-tube within the choledochotomy in order to drain bile and prevent bile leakage. In addition, persistently retained stones may be removed via the T-tube tract. Once the tract has been well established, it is reasonable to approach stone extraction percutaneously. Typically the tract is well established between 2 and 3 weeks postoperatively. In this event, the surgical endoscopist would remove the T-tube while maintaining the patency of the tract. After dilation, the endoscope can be introduced to retrieve retained stones. Alternately, ERCP may be used for postoperative stone retrieval, particularly in the absence of a T-tube. Although laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and stone extraction is successful in some hands, at this point it is not a commonly accepted technique.

A retained stone is a likely culprit if a patient postoperative from gallstone surgery is draining a high amount of bile through a drain, develops postoperative jaundice, or has clinical signs of cholangitis. In a review of such patients published in 2002, Yamaner et al. found that 46.6% (195 patients) had a retained common bile duct stone on ERCP.

References:

Garden OJ. Cholecystotomy, cholecystectomy and intraoperative evaluation of the biliary tree. In: Fischer JE, Bland KI, eds. Mastery of Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1114.

Tu Z, Li J, Zin H, et al. Primary choledochorrhaphy after common bile duct exploration. Dig Surg. 1999;16(2):137-139.

Yamaner S, Bilsel Y, Bulut T, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of complications following surgery for gallstones. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1685-1690.

1G17

Key word: Treatment of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anal Canal

Authors: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD, and Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Susan L. Gearhart, MD

A 65-year-old man presents with rectal pain, pencil-thin stools, and occasional bright red blood per rectum. A rectal examination under anesthesia reveals a 1-cm raised lesion at the anal verge, and extending for 3 cm proximally. There are no palpable lymph nodes or signs of systemic disease. Biopsy demonstrates squamous cell carcinoma. Which of the following is the standard therapy for this disease?

Abdominoperineal resection with permanent colostomy

Abdominoperineal resection with total mesorectal excision and bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection

Chemoradiation therapy with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C

Chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin

Low anterior resection

View Answer

Answer: (C) Chemoradiation therapy with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C

Rationale:

In the absence of nodal disease, T2 cancer of the anal canal can be treated with chemoradiation therapy with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C. Cisplatin may be used in place of

mitomycin C, especially as salvage chemotherapy. Wide local excision is reserved for patients with T1 and small T2 lesions and those with persistent disease following chemoradiation. Although abdominoperineal resection with permanent colostomy was the standard of care in the past, the desire to avoid permanent colostomy has led to trials supporting chemoradiation therapy alone. Abdominoperineal resection is reserved for disease recurrences. Inguinal lymph node dissection is directed at patients with inguinal nodal involvement.

Reference:

Silberfein EJ, Chang GJ, You Y-QN, et al. Cancer of the colon, rectum, and anus. In: Feig BW, Ching CD, eds. The M.D. Anderson Surgical Oncology Handbook. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

1G18

Key word: Most Common Etiology of Common Bile Duct Injury in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Author: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Mark D. Duncan, MD, FACS

What is the most common etiology of common bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy?

Acute or chronic inflammation

Bleeding

Congenital anatomic anomalies

Excess cephalad retraction of the gallbladder

Obesity

View Answer

Answer: (D) Excess cephalad retraction of the gallbladder

Rationale:

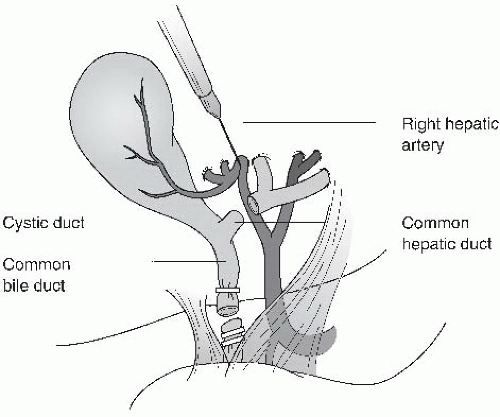

Although all the options above may contribute to the surgeon mistaking the common bile duct for the cystic duct, the classic mistake is to retract too forcibly on the fundus in the cephalad direction. This causes the common bile duct and cystic duct to align in the same plane, making their identity difficult to discern. This arrangement may lead to inadvertent clipping and transection of the common bile duct. Misidentification of ductal anatomy can be minimized by achieving the “critical view” achieved by dissecting along the inferior and medial aspects of the gallbladder between the liver bed and gallbladder/cystic duct junction. Visualizing the window in Calot triangle (the “critical view”) should demonstrate only the cystic duct and cystic artery going to the gallbladder.

The occurrence of bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy ranges from 0.3% to 0.7%.

Reference:

Lillemoe KD. Biliary injuries and strictures and sclerosing cholangitis. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

1G19

Key word: Treatment of Duodenojejunal Adenocarcinoma

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Michael A. Choti, MD, MBA

A 76-year-old man undergoes exploratory laparotomy for a suspected bowel obstruction. During the operation, you discover a mass in the duodenum just proximal to the ligament of Treitz, with no palpable lymphadenopathy. Intraoperative pathology confirms adenocarcinoma. What is the best course of management for this patient?

Gastrojejunostomy

Local resection with primary repair

Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Surgical resection with duodenojejunostomy

Surgical resection with intraoperative chemotherapy

View Answer

Answer: (D) Surgical resection with duodenojejunostomy

Rationale:

Of the malignant tumors of the small bowel, approximately 50% are adenocarcinomas. Forty percent of these occur in the duodenum, of which two-thirds are periampullary lesions. Most patients with small bowel adenocarcinoma present with advanced disease (stage III or IV). When possible, surgical resection is the treatment of choice. Ideally, preoperative diagnosis and staging is best in order to determine resectability and plan therapy. In this case, the diagnosis was made intraoperatively without the advantage of imaging to rule out extent of disease. However, if the tumor appears resectable at surgery, this approach can be considered. Principles of surgical therapy include en bloc resection incorporating the mesentery. In case of tumors located in the first and second portions of duodenum, pancreaticoduodenectomy will likely be required. For tumors in the distal duodenum or proximal jejunum as in this case, pancreas preserving resection with duodenojejunostomy is preferred, often requiring the anastomosis to the second portion of the duodenum. When unresectable and resulting in obstruction, gastrojejunostomy can offer palliation.

References:

Hrabe JE, Cullen JJ. Management of small bowel tumors. In: Cameron JL, Cameron AM, eds. Current Surgical Therapy. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2011;106-109.

Spalding DR, Isla AM, Thompson JN, et al. Pancreas-sparing distal duodenectomy for infrapapillary neoplasms. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(2):130-135.

1G20

Key word: Treatment of a Dark Stoma Following Abdominoperineal Resection

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Mark D. Duncan, MD, FACS

Two days after undergoing an abdominoperineal resection, a 64-year-old man’s colostomy stoma is dusky. On evaluation at the bedside on postoperative day 3, the dark bowel extends below the level of the abdominal wall fascia. What is the most appropriate management?

Arteriography

Bedside debridement

Exploration and revision in the operating room

Initiate wet-to-dry dressings to stoma

Observation

View Answer

Answer: (C) Exploration and revision in the operating room

Rationale:

Dark bowel in a colostomy signals poor perfusion of the terminal bowel, either due to disruption of the vascular arcade during surgical skeletonization, or from passing the bowel through too small an aperture in the abdominal wall fascia. While retraction of bowel below the level of the skin will result in chronic irritation in ileostomies, this is usually not the case with colostomies. Necrosis of colon below the level of the skin but above the fascia leads to a retracted stoma. However, this bowel will remain viable and does not require urgent repair, and may be managed by observation. On the other hand, necrosis of bowel below the fascia must be corrected by surgical revision of the stoma. A good dictum regarding the creation of colostomies is that the colostomy will not look better 2 days postoperatively than it does in the operating room. Any stoma that appears dusky in the operating room will only worsen in the postoperative period, and warrants strong consideration for immediate revision.

Intraoperatively, attention should be paid to the health of the remaining colon, the mesenteric vessels, and alignment such that undue stretch or torsion on the mesentery is avoided.

Reference:

Kann BR. Early stomal complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2008; 21(1): 23-30.

1G21

Key word: Diagnosis of Acute Gastric Dilation

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editors: Christopher L. Wolfgang, MD, PhD, and Matthew J. Weiss, MD

After undergoing resection of the right middle lobe of her lung, a 65-year-old woman complains of acute abdominal pain while eating breakfast in the morning. Her stomach is distended and tympanitic, she is bradycardic, hypotensive, tachypneic, and sweating profusely. What is the most appropriate next course of action?

Emergency exploratory surgery

Increase the patient’s pain medication

Obtain supine and erect abdominal x-rays

Perform esophagogastroscopy

Place a nasogastric tube

View Answer

Answer: (E) Place a nasogastric tube

Rationale:

The patient is experiencing acute gastric dilation. Acute gastric dilation can occur in patients following any surgical procedure involving anesthetics and analgesics. The cause is sudden distension of the stomach, resulting in a vagal response. The ensuing symptoms are abdominal pain, tachypnea, pallor, sweating, bradycardia, and hypotension. If untreated, acute gastric dilation can lead to vomiting, which can result in aspiration, bleeding from erosive gastritis, and possible esophageal perforation.

Initial diagnosis relies on clinical acumen as well as examination. Classically, patients have a distended and tympanitic stomach. Confirmation of diagnosis may be obtained by placement of a nasogastric tube, resulting in rapid decompression. In addition, nasogastric decompression is the treatment for acute gastric dilation, which usually lasts 24 to 48 hours until motility is regained.

Reference:

Moody FG, McGreevy, JM, Miller TA. Stomach. In: Schwartz SI, Shires GT, Spencer FC, eds. Principles of Surgery. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1989:1157-1188.

1G22

Key word: Diagnosis of Common Bile Duct Stricture from Chronic Pancreatitis

Author: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Michael A. Choti, MD, MBA

A 48-year-old alcoholic man with painless jaundice appears to have intrahepatic biliary ductal dilation on computed tomography (CT) scan. The bilirubin is 12.6 with other liver function tests normal. On review of the CT scan, you can detect no obstructing mass. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) demonstrates no stones in his biliary tree with dilation extending to the pancreas. The most likely cause of his ductal dilation is:

Abdominoperineal resection with total mesorectal excision and bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection

Abdominoperineal resection with total mesorectal excision and bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection