Gastroenterology

William R. Brown

Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease

What is the pathogenesis responsible for chronic ulcerative colitis (CUC) and Crohn’s disease?

Compare and contrast the principal clinical features of CUC and Crohn’s disease.

What are the respective risks of intestinal malignancy in CUC and Crohn’s disease?

What are the principal medical therapeutic measures used for patients with CUC and Crohn’s disease?

Discussion

What is the pathogenesis responsible for CUC and Crohn’s disease?

The cause and pathogenesis of both these chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (CIBDs) are unknown. Both are characterized by a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate of the bowel. However, whereas CUC is restricted to the colon, Crohn’s disease can involve the entire alimentary tract from the mouth to the anus, although the distal ileum and colon are the portions most frequently affected. Another distinguishing feature of Crohn’s disease is the involvement of all layers of the bowel, whereas the inflammation seen in CUC is mostly limited to the mucosa. In addition, focal granulomas are common in Crohn’s disease but rare in CUC. However, neither disease has pathognomonic features, and Crohn’s disease of the colon cannot be histologically distinguished from CUC in 15% to 25% of cases of chronic colitis.

Compare and contrast the principal clinical features of CUC and Crohn’s disease.

The severity, clinical course, and prognosis of CUC and Crohn’s disease are widely variable. Onset in both diseases occurs most often in early adulthood. The symptoms of CUC may range from slight rectal bleeding to fulminant diarrhea with colonic hemorrhage and hypotension. Most patients have intermittent attacks, although some can have continuous symptoms without remission. The clinical features of Crohn’s disease depend on the severity and location of the bowel involvement; the principal features are diarrhea, abdominal pain, hematochezia, intestinal obstruction, fissures, and fistulas.

Extraintestinal manifestations are common in both Crohn’s disease and CUC, but more common in CUC. The manifestations include arthritis, arthralgia, iritis, uveitis, liver disease, and skin lesions. The arthritis may present as a migratory arthritis, involving large joints, sacroiliitis, or ankylosing spondylitis. Primary sclerosing cholangitis, which is associated with an increased frequency of cholangiocarcinoma, and chronic hepatitis are common hepatobiliary abnormalities.

The principal features that differentiate Crohn’s disease from CUC are listed in Table 4.1.

What are the respective risks of intestinal malignancy in CUC and Crohn’s disease?

The frequency of intestinal cancer is increased in Crohn’s disease, but not to the extent in CUC. According to some reports, the frequency of colon cancer in adults who have CUC involving the entire colon is approximately 25 times greater than that in the general population. The risk of colon cancer developing in patients with CUC is positively correlated with the extent and duration of the disease.

What are the principal medical therapeutic measures used for patients with CUC and Crohn’s disease?

The general measures to control the symptoms of both diseases include correction of fluid–electrolyte imbalances; iron, folate, or vitamin B12 supplementation as needed for the treatment of anemia; and dietary adjustments aimed at maintaining adequate nutrition. Total parenteral nutrition may be

required for the short-term treatment of severe acute disease, but “bowel rest” and hyperalimentation are of dubious value in the long term. Antidiarrheal agents such as loperamide are usually contraindicated in patients with CUC because they may contribute to the development of toxic megacolon, but they may help alleviate the diarrhea and abdominal cramps in the setting of stable Crohn’s disease.

Table 4-1 Features that Distinguish between Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis

Factors

Crohn’s Disease

Ulcerative Colitis

Pathologic features

Transmural inflammation

Mucosal inflammation

Deep ulcers

Superficial ulcers

Granulomas common

Granulomas absent

Distribution

Mouth to anus (ileum and proximal colon most common)

Colon

Clinical features

Rectal bleeding

20%–40%

98%

Fulminating episodes

Uncommon

Common

Obstruction

Common

Rare

Fistulas

Common

Rare

Perianal disease

Common

Less common

Sigmoidoscopic and

radiographic findings

Rectal involvement

50%

95%–100%

Extent

Patchy

Continuous

Ulcers

Longitudinal, deep

Shallow, collar button

Pseudopolyps

Uncommon

Common

Strictures

Common

Uncommon

Ileal involvement

Narrowed lumen with thickened wall

Dilated lumen with diminished folds but histologically normal

From Schaefer J, Mallory A. Gastrointestinal disease. In: Schrier RW, ed. Medicine: diagnosis and treatment. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1988.

In CUC, corticosteroids are useful for inducing remissions or improvement in an acute attack, and they may be required for long-term management. However, the possible benefits of corticosteroids in the long term are offset by their many adverse side effects. The rectal administration of steroids or mesalamine can be beneficial, especially when rectal involvement (proctitis) is severe. However, significant absorption of rectal steroids can occur, so systemic effects of the agents (both beneficial and undesirable) may arise when they are given by this route. Sulfasalazine is metabolized by colonic bacteria, releasing sulfapyridine and 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA); the latter is believed to be the

active compound. Sulfapyridine is absorbed systemically, which accounts for the side effects of sulfasalazine (e.g., headache, occasional megaloblastic anemia, skin rash). The greatest utility of sulfasalazine in patients with CUC is in long-term management, where it has been proved to reduce the frequency of relapses. 5-ASA, given rectally by enema or suppository, is well tolerated and effective. Given orally, 5-ASA is rapidly denatured by gastric acid, so alternatives to plain 5-ASA, such as microencapsulated (Pentasa; Hoechst Marion Roussel, Kansas City, MO) or acrylic-based resin-coated (Asacol; Procter & Gamble Pharmaceutical, Norwich, NY) forms of 5-ASA, may be used. Because the relative risk for development of CUC is greater in nonsmokers than in smokers (the opposite is true in Crohn’s disease), nicotine is being tried in the treatment of CUC; some benefit has been reported, but additional research is needed.

There is no uniformly effective treatment available for Crohn’s disease. However, corticosteroids have documented efficacy in diminishing the activity of the disease process. Long-term use of corticosteroids is not recommended because of their many side effects, such as osteoporosis, diabetes, and cataracts. Sulfasalazine has some effectiveness, especially in colonic Crohn’s disease, but is less effective than corticosteroids. Pentasa, in doses of more than 3 mg per day may be efficacious in mild to moderate Crohn’s disease, particularly in ileal disease. Metronidazole may be at least as effective as sulfasalazine. When Crohn’s disease cannot be controlled by these medications, the immunosuppressive agent azathioprine and its metabolite 6-mercaptopurine are often used. These drugs are effective in both inducing and maintaining remission in inflammatory-type and fistulizing-type Crohn’s disease. Their use can result in a reduction in the corticosteroid dose needed, but this advantage may be offset by their toxic effects (e.g., pancreatitis, allergic reactions, and leucopenia). More recently, infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antitumor necrosis factor antibody, has been shown to be effective in Crohn’s disease, both in the inflammatory and the fistulizing types. The role of immunodulator drugs in CUC is less clear than in Crohn’s disease.

Case

A 37-year-old man with documented CUC was first seen at 19 years because of severe bloody diarrhea and left lower quadrant abdominal pain that necessitated hospitalization. After 10 days of treatment with high-dose prednisone and sulfasalazine his symptoms were controlled, and he has since been managed with these medicines, with the dosages adjusted depending on his disease activity. He has not required corticosteroids except for flare-ups of disease. Subsequent to his initial presentation, after his disease activity had subsided, he underwent colonoscopy for histologic confirmation of the disease and to determine the extent of intestinal involvement; this examination revealed diffuse mucosal inflammation involving the entire colon (pancolitis). The terminal ileum appeared normal. Colonic biopsy specimens revealed a diffuse mucosal inflammatory infiltrate with little involvement of the submucosa, acute and chronic inflammatory cells, and frequent crypt abscesses but no granulomas.

The patient went on to graduate from college and was then hired as a sales representative for a pharmaceutical company. Because his disease has been quiescent and his schedule very busy he has not taken his medications regularly and has rarely seen his physician.

Approximately 2 months ago, he began to feel tired, and intermittent rectal bleeding developed. His physical examination findings are unremarkable, but the fecal occult blood test result is positive. The hemoglobin is 11 g/dL; hematocrit, 33%; and leukocyte count, 7,700 cells/mm3, with a normal differential count.

What is your differential diagnosis of his recent symptoms?

What tests are necessary to make the correct diagnosis?

How should this patient’s CUC have been managed over the previous 18 years?

Case Discussion

What is your differential diagnosis of his recent symptoms?

The differential diagnosis in this patient includes three possibilities. First, this episode could be an acute flare-up or exacerbation of his ulcerative colitis. Second, he could have an acute, self-limited colitis superimposed on his ulcerative colitis; infection with Campylobacter, Salmonella, or Shigella species, or with parasites can cause such a colitis. Third, the rectal bleeding and anemia could be the result of adenocarcinoma.

What tests are necessary to make the correct diagnosis?

Stool cultures and the examination of stool for ova and parasites would be an important initial laboratory test in this patient. These proved to be negative.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy with the acquisition of biopsy specimens is also an important diagnostic procedure. In contrast to CIBD, the histologic features of acute self-limited colitis consist of normal crypt architecture and an acute but not chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria. Inflammation is more likely to be found in the upper mucosa in acute colitis, and in the crypt bases in CIBD. When an acute self-limited colitis, such as infection with Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella, or Shigella, resolves, the mucosa is normal, whereas crypt distortion and atrophy are often seen in the setting of healed CIBD. In other acute colitides, the histologic features found in mucosal biopsy specimens may suggest a specific infection; these include viral inclusions, parasites, or pseudomembranes.

In this patient, flexible sigmoidoscopy was performed to a depth of 30 cm and revealed mild granularity of the mucosa without bleeding, although some blood was seen coming from above 30 cm. Active CUC almost always involves the rectum, so the finding of only mild changes in this patient’s rectum suggests that the significant pathologic process was higher in the colon. A colonoscopic examination showed a sessile, fungating mass in the descending colon, which proved to be an adenocarcinoma.

How should this patient’s CUC have been managed over the previous 18 years?

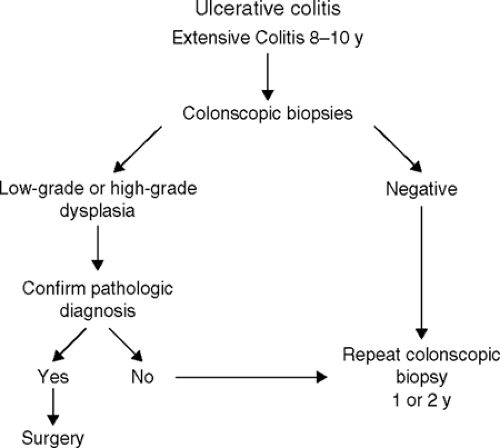

There is not yet agreement on the most cost-effective approach for the surveillance for colonic cancer in patients with CUC. However, after a patient has

had extensive disease for 8 to 10 years, it is probably wise to perform complete colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years, with multiple biopsy specimens obtained every 10 to 12 cm from normal-appearing mucosa and targeted specimens obtained from villous areas of mucosa, areas of ulceration with a raised edge, and strictures. Colectomy is recommended if multifocal or high-grade dysplasia is seen in the biopsy specimens and confirmed by an experienced pathologist. If a mass lesion associated with any degree of dysplasia is identified, this is also a generally accepted indication for colectomy. The management of persistent low-grade dysplasia without a mass is more controversial, but, increasingly, colectomy is being recommended for low-grade dysplasia (Fig. 4.1).

Cancer prevention is an important topic to consider when advising young patients with extensive colitis about the possible need for surgical treatment. The decision to recommend prophylactic proctocolectomy after many years of colitis must be based on several considerations in the individual patient. These include the intractability of symptoms, age, psychological makeup, medical compliance, and the availability of newer surgical procedures. A prophylactic colectomy should be recommended to a noncompliant patient who acquires extensive ulcerative colitis at a young age. Patients who have CUC should be fully informed of their risk for development of cancer, as well as the limitations of endoscopic surveillance and the availability of surgical alternatives. If a patient is unwilling to assent to the surgical procedure, then he or she must be committed to undergoing regular surveillance.

Suggested Readings

Jewell DP. Ulcerative colitis. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2002: 2039–2067.

Sands BE. Crohn’s disease. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2002: 2005–2038.

Stenson WF, Korzenik J. Inflammatory bowel disease. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Kaplowitz N, etal. eds. Textbook of gastroenterology, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003: 1699.

Chronic Liver Disease

What are some specific causes of chronic liver disease?

What are the principal laboratory abnormalities in the setting of chronic liver disease?

What are the two major histologic categories of chronic hepatitis due to viral infection?

Discussion

What are some specific causes of chronic liver disease?

Chronic liver disease may be the sequela of several kinds of toxic, metabolic, infectious, immunologic, or hereditary conditions. Table 4-2 contains a partial list.

What are the principal laboratory abnormalities in the setting of chronic liver disease?

The clinically available liver function tests include those that assess, at least in part, liver synthetic function (serum albumin and bilirubin concentrations, and prothrombin time) and those that mostly evaluate the hepatocellular release of enzymes (aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase). Often, the levels of aminotransferase [alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase] are not markedly elevated in patients with chronic liver disease, and consequently do not accurately predict prognosis. The serum albumin and bilirubin concentrations and the prothrombin time are more likely to be distinctly abnormal, and more accurately reflect the true status of the liver’s functional capacity.

What are the two major histologic categories of chronic hepatitis due to viral infection?

Categories of these diseases, constructed by international committees, consist of three components: the etiology of the diseases, grading of disease activity (i.e., the severity of the necroinflammatory process), and staging of the disease (i.e., the degree of fibrosis subsequent to necroinflammatory insults). The grading and staging are usually given a semiquantitative score (0 to 4) or a descriptive characterization (e.g., minimal to severe inflammation, or no fibrosis to cirrhosis).

Table 4-2 Specific Causes of Chronic Liver Disease | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Case

A 60-year-old man is brought to the hospital by his wife because he has not been acting his usual self. For the last 3 days, he has not been sleeping at night and has been napping during the day. There is no history of recent trauma, taking new medications, or suicidal ideation. He has been taking diazepam, 5 mg nightly, for insomnia. Risk factors for chronic liver disease, according to his wife, include the consumption of two beers nightly for 35 years and a blood transfusion for the treatment of a bleeding peptic ulcer 25 years ago, at which time he underwent an “ulcer surgery.”

On physical examination, he appears sleepy but arousable. The vital signs are normal. Several large spider angiomas are present on the torso. There is no scleral icterus. The parotid glands are enlarged bilaterally, and wasting of the temporal muscles is noted. The heart and lung examination findings are normal. His abdomen is slightly distended, and

shifting dullness and a midline scar are present. The liver is not palpable below the right costal margin but is palpable 10 cm below the xiphoid process; it is firm and percussed to a span of 8 cm in the right midclavicular line. The spleen is palpable. The abdomen is not tender to palpation or percussion. The testes are small. The rectum is found to contain hard, brown stool, which is positive for occult blood. There is mild edema of the legs and moderate muscle wasting. Asterixis is present. The cranial nerves and deep tendon reflexes are intact. The patient is somewhat uncooperative but his muscular strength is not focally diminished; his plantar reflexes (Babinski’s sign) are normal.

shifting dullness and a midline scar are present. The liver is not palpable below the right costal margin but is palpable 10 cm below the xiphoid process; it is firm and percussed to a span of 8 cm in the right midclavicular line. The spleen is palpable. The abdomen is not tender to palpation or percussion. The testes are small. The rectum is found to contain hard, brown stool, which is positive for occult blood. There is mild edema of the legs and moderate muscle wasting. Asterixis is present. The cranial nerves and deep tendon reflexes are intact. The patient is somewhat uncooperative but his muscular strength is not focally diminished; his plantar reflexes (Babinski’s sign) are normal.

Laboratory data are as follows: peripheral blood white cell count, 2,500 cells/mm3; hemoglobin, 10 g/dL; hematocrit, 33%; platelet count, 125,000/ mm3; serum AST, 100 IU/L (normal, <30 IU/L); ALT, 80 IU/L (normal, <45 IU/L); total bilirubin, 1.2 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 150 IU/L (normal, <130 IU/L); total protein, 8.0 g/dL; albumin, 3.1 g/dL; and prothrombin time, 13 seconds (control, 11 seconds).

What features help you to diagnose chronic versus acute liver disease in this patient?

Does any particular factor help you determine the cause of this man’s liver disease?

What reversible factors could be contributing to this man’s presumed portosystemic encephalopathy (PSE)?

When, if ever, should this man’s ascites be sampled? If it should, how and where should it be sampled?

What are three possible explanations for the occult blood in his stool?

What is the serum–ascites albumin gradient, and of what value is it?

Would you start diuretic therapy now? Why or why not?

Why are his testes small?

Why are his parotid glands enlarged?

Is this man at increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma?

How would you exclude hepatocellular carcinoma?

What is included in your differential diagnosis of this man’s chronic liver disease?

Why is hepatitis A not in your differential diagnosis?

The results of additional tests are available within 4 hours of admission. The ascites is sampled from a left lower quadrant paracentesis, yielding a clear yellow fluid with a white blood cell count of 380 cells/mm3, 2% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, an albumin concentration of 0.5 g/dL, and a total protein level of 1 g/dL. No organisms are seen on Gram’s-stained specimens.

Do the findings from the additional tests on the ascitic fluid support the diagnosis of portal hypertension-associated ascites? Why or why not?

With these data in mind, what treatment would you offer this patient now, and why?

What areas of the patient’s history should you examine at greater length, and why?

Would you offer this patient a liver biopsy and, if so, when?

Case Discussion

What features help you to diagnose chronic versus acute liver disease in this patient?

In this patient, there are no pathognomonic features of chronic liver disease, but several that suggest this condition. Large spider angiomas are common in

the setting of chronic liver disease, but not acute liver disease, although small, nonpalpable spider angiomas may be present. Muscle wasting is common in moderately advanced chronic liver disease, but is not due to poor eating habits. Muscle wasting is not a feature of acute liver disease unless it is the result of a concomitant, unrelated problem. A palpable, firm left lobe of the liver (that portion palpable caudad to the xiphoid process) is usually a manifestation of chronic liver disease. It is always important to palpate and percuss for the liver in the midline, as well as in the midclavicular line. Ascites, due to portal hypertension, is much more a feature of chronic liver disease than of any other disorder. Ascites may occur in the setting of severe acute liver disease, but it is usually not of significant quantity to warrant treatment. One notable exception is the Budd-Chiari syndrome, in which there may be ascites, although the abdominal distention in this syndrome is partially due to a congested and enlarged liver stemming from the hepatic vein occlusion. Shifting dullness is indicative of a large amount (>1.0 to 1.5 L) of ascites.

Pancytopenia is related to the splenic sequestration of blood cells and is not a prominent feature of liver disease unless the spleen is affected; when it is, it is usually enlarged. The degree of pancytopenia (or of individual cytopenias) may not correlate with spleen size. Hepatitis C may be associated with the development of aplastic anemia, but this is rare. Transient cytopenias may be seen in hepatitis, as in other viral infections. A low serum albumin level may be seen in any form of liver disease that has lasted for more than several weeks. A high serum globulin (total protein-albumin) level is a feature of chronic liver disease regardless of the cause. Extremely high serum globulin levels (i.e., ≥10 g/dL) should suggest the possibility of autoimmune or “lupoid” hepatitis; this disorder is usually seen in women and is frequently accompanied by other autoimmune features, such as thyroiditis. Autoimmune hepatitis is important to recognize because it can usually be treated with corticosteroids.

Does any particular factor help you determine the cause of this man’s liver disease?

There are no particular factors that point to the cause of this patient’s liver disease. The major differential diagnoses here are alcoholic liver disease and chronic active hepatitis (hepatitis C from his blood transfusion), probably in the cirrhotic stage. No feature of his history, physical examination, or routine laboratory tests helps distinguish between these two causes.

What reversible factors could be contributing to this man’s presumed PSE?

Benzodiazepines, other sedative or hypnotic drugs, and opiates may precipitate PSE in a patient with severely impaired hepatic function. Constipation may also precipitate PSE in susceptible patients because of the colonic absorption of nitrogenous products. Both these reversible risk factors are present in this patient. Other reversible factors contributing to an episode of PSE include electrolyte disturbances, notably hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis; increased intestinal absorption of nitrogenous products, resulting from relatively excessive dietary protein intake or an upper gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage; and a serious infection of any nature. In patients with chronic liver disease who have acute PSE, culture of the body fluids—ascitic fluid, blood, urine, and sputum—should be done. This patient’s PSE indicates that he has severe liver disease.

When, if ever, should this man’s ascites be sampled? If it should, how and where should it be sampled?

Diagnostic paracentesis should be performed as soon as possible to determine whether the patient has subacute bacterial peritonitis. This form of infectious peritonitis is a frequent cause of clinical deterioration in patients with chronic liver disease, and may be fatal if not recognized and treated early.

The three safest locations for paracentesis are the left lower quadrant, right lower quadrant, and the infraumbilical midline area. A supraumbilical approach should never be used because the umbilical or paraumbilical vessels, which course just under the parietal peritoneum, are frequently recanalized in patients with portal hypertension whose portal vein is patent. It is also important to always stay clear of (medial or lateral to) the rectus muscles because the superficial epigastric vessels course under them and may be punctured. Skin puncture through or near an abdominal scar in a patient with suspected or known portal hypertension should always be avoided.

What are three possible explanations for the occult blood in his stool?

Three possible explanations are (a) portal hypertensive gastropathy or enteropathy, (b) rectal varices, and (c) esophageal variceal hemorrhage due to portal hypertension. Variceal bleeding is usually a sudden event of large volume, although uncommonly varices “ooze.”

What is the serum–ascites albumin gradient, and of what value is it?

The serum–ascites albumin gradient is the numeric difference (not ratio) between the serum albumin concentration and the ascites albumin concentration. When the gradient is 1.1 or greater, portal hypertension is contributing to or entirely causing the ascites. When the gradient is less than 1.1, peritoneal carcinomatosis or inflammatory diseases are likely causes of the ascites. On the basis of this man’s history, the two main causes to be considered are portal hypertension and peritoneal malignancy. Determination of the serum–ascites albumin difference is a simple, minimally invasive, and fairly accurate way to diagnose portal hypertension.

Would you start diuretic therapy now? Why or why not?

No. Diuretics are not essential now, and they may only worsen the PSE and increase the risk of hepatorenal syndrome.

Why are his testes small?

In the setting of hepatic disease, the production of estrone from circulating androstenedione may be increased. The exact cause of this conversion is unknown but may be related to the decreased clearance of androstenedione by the liver. The consumption of excessive amounts of ethanol may also have contributed to the testicular atrophy in this patient.

Why are his parotid glands enlarged?

Parotid enlargement is seen in people who ingest excessive amounts of ethanol, and is associated with fatty infiltration of the glands. A similar situation may be seen in diabetic patients.

Is this man at increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma?

Yes. There is a risk for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in the setting of any form of cirrhotic liver, which this man most likely has. Certain conditions

are associated with higher risks than others. Those associated with highest risk are genetic hemochromatosis, chronic hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis C, and alcoholic liver disease.

How would you exclude hepatocellular carcinoma?

Useful tests for identifying hepatocellular carcinoma are an imaging test [ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging] and a serum α-fetoprotein level. The preferred imaging test (to exclude a focal lesion) depends on the expertise of the institution. Arterial-phase CT is regarded as most reliable. Hepatocellular carcinomas are especially difficult to detect in cirrhotic livers; therefore it is important that arterial-phase CT be used in this setting. The serum α-fetoprotein level is very high in 60% of patients with alcoholic liver disease who have a superimposed hepatocellular carcinoma and in approximately 80% to 90% of patients with chronic hepatitis B who have this complication.

What is included in your differential diagnosis of this man’s chronic liver disease?

The differential diagnosis in this patient includes alcoholic liver disease and chronic active hepatitis with cirrhosis, due to either hepatitis B or C, although hepatitis should be regarded as the more likely diagnosis. The hepatitis viruses may have been transmitted to him by the blood he received many years ago, or they may have been “sporadically” acquired.

Why is hepatitis A not in your differential diagnosis?

Hepatitis A has never been reported to cause chronic liver disease.

Do the findings from the additional tests on the ascitic fluid support the diagnosis of portal hypertension-associated ascites? Why or why not?

Yes, the findings from the tests on the ascitic fluid do support the diagnosis of portal hypertension-associated ascites because the serum–ascites albumin gradient (2.6) exceeds 1.1. There are two caveats to remember when using the serum–ascites albumin gradient in the diagnosis of ascites. First, if massive hepatic metastases cause enough liver disease to result in portal hypertension and ascites, the gradient resembles that seen in portal hypertension. Second, in ascites of mixed etiology (e.g., portal hypertension plus tuberculous peritonitis), the gradient usually resembles that seen in the setting of portal hypertension.

With these data in mind, what treatment would you offer this patient now, and why?

Hospital admission is required. Strict bed rest (for fear of self-harm) seems prudent. No benzodiazepines should be administered, although the patient should be monitored for the signs of ethanol withdrawal—agitation, tachycardia, fever, and hallucinosis. The patient should receive an enema if he is constipated. Lactulose should also be administered (by mouth or nasogastric tube) if the patient becomes too disoriented and uncooperative. The oral or nasogastric lactulose dose is variable; the goal of therapy is to produce two to three soft stools per day. Alternatively, a nonabsorbable antibiotic could be used, such as neomycin at a dosage of 500 to 1,000 mg given orally or by nasogastric tube every 6 hours, or rifaximin. There is no evidence that giving lactulose and an antibiotic together is more effective than administering either alone. Lactulose is probably beneficial in the treatment of PSE by virtue of its ability to decrease the amount of nitrogen available for absorption (as urea) from the colon. Lactulose may accomplish this

by altering the colonic flora to more urease-negative forms and by inducing an osmotic diarrhea.

What areas of the patient’s history should you examine at greater length, and why?

One area of the patient’s history that should be examined at greater length is his ethanol consumption history. This involves more interviewing of his family and friends. The alleged amount of ethanol ingested (per the patient’s wife) is too low to cause liver disease in men because the alcohol content of two cans of beer is approximately 12 g. However, the parotid gland enlargement and testicular atrophy are findings that suggest his ethanol ingestion has been more than he has admitted. The amount and duration of alcohol ingestion necessary to cause chronic liver disease is highly variable among individuals, although the incidence of biopsy-proved cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, or both, increases as consumption is increased. It is usually believed that the threshold amount of alcohol consumption that leads to these serious forms of chronic liver disease is in the order of 100 to 150 g per day for several years in men, but less in women. However, a large proportion of heavy drinkers do not contract serious liver diseases. It is advisable to record alcohol consumption in terms of grams per day times the number of years of consumption. A quart of 80 proof whiskey contains approximately 300 g of ethanol, a six-pack of 4% beer approximately 75 g, and 750 mL of wine approximately 90 g (150 g for “fortified” wine).

A second area of inquiry should be the patient’s family history. In this patient, you should also ask whether anyone in the family has had liver disease, including genetic hemochromatosis. You might phrase the question in this way: “Do you have any family members who have conditions that require blood to be removed as treatment?” The manifestations of hemochromatosis may differ in various family members, and may consist of cardiomyopathy, diabetes, arthritis, or pituitary insufficiency. In this patient, the small liver is inconsistent with a diagnosis of hemochromatosis, although all else is. Moreover, he is an older man—the typical age and sex of patients who have severe chronic liver disease caused by hemochromatosis.

Would you offer this patient a liver biopsy and, if so, when?

A liver biopsy would be of no help in the initial management of his decompensated liver disease. However, when conclusive documentation of the diagnosis would help determine management, liver biopsy might be important. This might be the case in a patient with suspected Budd-Chiari syndrome because it is often treatable by hepatic decompression (as, e.g., with a side-to-side portacaval anastomosis), or it might be the case in a patient with hemochromatosis. Once the patient’s condition has stabilized, a liver biopsy might be offered, for three reasons. First, he may be a candidate for specific therapy. However, it is unlikely that there is any therapy for this patient. If, as seems likely, he has alcoholic cirrhosis there is no effective treatment other than abstinence; if he has hepatitis C–related cirrhosis, interferon treatment may be dangerous because of the hepatocytolysis brought about by therapy. Second, some authorities believe that liver biopsy is indicated in patients with suspected alcoholic liver disease because confirmation of that diagnosis might help persuade the patient to abstain from further ethanol ingestion. Third, if the patient becomes a candidate for hepatic transplantation, most centers require a definitive preoperative diagnosis before going ahead with the procedure.

Suggested Readings

Batts KP, Ludwig J. Chronic hepatitis: an update on terminology and reporting. Am J Pathol 1995;19: 1409.

Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. In: Schiff ER, Sorrell MF, Maddrey WC, eds. Schiff’s diseases of the liver, 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003: 1019–1057.

Davis GL. Hepatitis C. In: Schiff ER, Sorrell MF, Maddrey WC, eds. Schiff’s diseases of the liver, 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003: 807–861.

Diarrhea

What is the diagnostic importance of nocturnal diarrhea in a patient with chronic diarrhea?

What is the difference between a secretory and an osmotic diarrhea?

What happens to diarrheal stool volume after fasting in the following settings: A vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) tumor, the abrupt onset of watery diarrhea after traveling outside of the United States, or diarrhea only when drinking large amounts of carbonated beverages?

What is the most likely cause of diarrhea in a patient who has recently taken ampicillin and then has low-grade fever and watery diarrhea? What is the most cost-effective way to diagnose this disease, and how would you treat this patient?

Why do patients with giardiasis often complain of increased stool volume and abdominal cramping when they consume milk products?

Which organisms are most commonly associated with diarrhea of less than 2 to 3 weeks’ duration, and what are their clinical characteristics? How are such cases evaluated, and what are the various approaches to treatment?

What is the utility of staining stool specimens for leukocytes?

What would the clinician look for if surreptitious laxative abuse is suspected as a cause of chronic diarrhea?

A 24-year-old woman who has had a recurring rectovaginal fistula for 2 years complains of frequent small-volume stools, which occasionally contain blood and mucus. Stool cultures yield negative findings. What is the likely disease in this woman who has a rectovaginal fistula, and what would be the next step in evaluating her?

Discussion

What is the diagnostic importance of nocturnal diarrhea in a patient with chronic diarrhea?

Nocturnal diarrhea suggests an organic cause of the diarrhea. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome or other “functional” diarrheas rarely have diarrhea that awakens them from sleep.

What is the difference between a secretory and an osmotic diarrhea?

Secretory diarrhea is due to the active secretion of water and electrolytes into the intestinal lumen. The mechanism of action responsible for the release of the secretagogues is variable. For instance, the diarrhea of cholera, the classic example of a secretory diarrhea, is caused by the stimulation of adenylate cyclase activity by cholera toxin; this, in turn, causes an increase in the intracellular concentration of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which stimulates electrogenic chloride secretion and inhibits electroneutral sodium chloride absorption. Increases in intracellular concentrations of Ca2+ as well as cyclic guanosine monophosphate have been proposed as the abnormalities at work in various other forms of secretory diarrhea.

In osmotic diarrhea, an unabsorbable solute (often a carbohydrate or divalent mineral) increases the osmolality of the intestinal contents. This increased osmolality passively “drags” water into the intestinal lumen. Patients with osmotic diarrhea usually have a stool osmolality measure that is much greater than that yielded by the formula: 2 × serum Na+ + serum K+; this condition constitutes an osmotic gap. A common osmotic diarrhea is that which occurs after the ingestion of milk or milk products in people who are deficient in the intestinal enzyme lactase, or those who ingest magnesium-containing antacids or laxatives.

What happens to diarrheal stool volume after fasting in the following settings: a VIP tumor, the abrupt onset of watery diarrhea after traveling outside of the United States, or diarrhea only when drinking large amounts of carbonated beverages?

VIP is produced by the intestinal mucosa in increased amounts in the WDHA (watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, and achlorhydria) syndrome. VIP causes diarrhea by stimulating mucosal adenylate cyclase activity, and therefore would be expected to cause a secretory diarrhea. In such a condition, fasting would not decrease the stool volume until the patient becomes severely dehydrated.

Typically, travelers’ diarrhea is watery and occurs within 3 to 6 days of arriving in another country, or on return. Symptoms usually last for 2 to 3 days and resolve spontaneously. The most common pathogens responsible are the enterotoxigenic strains of Escherichia coli, which can elaborate heat-labile and heat-stable enterotoxins. The heat-labile toxin acts similarly to cholera toxin, whereas the heat-stable toxin stimulates mucosal guanylate cyclase activity. Other types of diarrhea-producing E. coli and their associated symptoms are the enteropathogenic type, which causes watery diarrhea, predominantly in children and newborns; the enteroinvasive type, which causes bloody diarrhea (dysentery) in children and adults, usually after the ingestion of contaminated food and water; and the enterohemorrhagic type, which causes bloody diarrhea in people of all ages and is transmitted through contaminated food (often poorly cooked hamburger). Serotype 0157:H7 of the enterohemorrhagic type has been identified in several outbreaks of infection characterized by particularly severe disease (hemolytic uremic syndrome).

Other pathogens associated with travelers’ diarrhea include Shigella and Salmonella species, C. jejuni, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Because of the numerous causes of traveler’s diarrhea, the effect of fasting is usually unpredictable.

The osmotic diarrhea that occurs only after drinking large amounts of carbonated beverages is due to the ingestion of large amounts of fructose, which is the sugar used to sweeten these beverages (although not diet drinks) and comes in the form of corn syrup. Fructose is poorly absorbed by the proximal small intestinal mucosa. Cessation of fructose intake should stop the diarrhea.

What is the most likely cause of diarrhea in a patient who has recently taken ampicillin and then has low-grade fever and watery diarrhea? What is the most cost-effective way to diagnose this disease, and how would you treat this patient?

Pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) caused by Clostridium difficile is a likely diagnosis in this instance, given the patient’s recent antibiotic use. The disease is usually self-limited, with the diarrhea dissipating 5 to 10 days after discontinuation of the offending antibiotic. Clindamycin was the first drug proved to cause PMC; later, ampicillin, because of its widespread use, was the drug most commonly implicated, but virtually any antibiotic can be responsible. In healthy adults, C. difficile colonization rates of 2% to 3% have been reported, whereas the rates in adults receiving antimicrobials but without diarrheal symptoms are as high as 10% to 15%.

The most commonly used method for diagnosing PMC is the cytotoxicity assay, which involves observation of the cytopathic effect produced by the toxin on a cell culture; the assay has a sensitivity of 95% to 97%. Although the latex agglutination test for the presence of toxin is both cheaper and faster to perform, it has a sensitivity of only approximately 85%. Gross colonic abnormalities in patients with PMC, which can be seen endoscopically, typically occur in the descending and sigmoid colon, making flexible sigmoidoscopy an adequate examination in most cases; however, cases with only right-sided involvement have been reported. The endoscopic findings in patients with PMC include erythematous, friable mucosa with characteristic pseudomembranes. Care must be taken to rule out bacterial or parasitic infections (especially C. jejuni and Entamoeba histolytica) and inflammatory bowel disease.

The recommended treatment for less severe cases of PMC consists of either oral metronidazole (250 mg four times a day) or vancomycin (125 to 500 mg four times a day). Parenteral doses of metronidazole [500 mg intravenously (IV) every 6 hours] should be given only when oral medication cannot be tolerated. The IV administration of vancomycin is not effective. The rates of relapse are similar for both metronidazole and vancomycin and range from 10% to 15%. Cholestyramine has been reported to be effective in the treatment of mild PMC or as an adjunctive measure, presumably by binding the toxin intraluminally. Cholestyramine may be used in conjunction with metronidazole but not with vancomycin, because it can bind and inactivate vancomycin. Recently, the oral administration of the nonabsorbed antibiotic rifaximin and probiotics (preparations of viable bacteria with therapeutic physiologic effects) has been reported effective in the treatment of recurrent PMC.

Why do patients with giardiasis often complain of increased stool volume and abdominal cramping when they consume milk products?

Giardia lamblia infection causes a deficiency in the intestinal disaccharidases, including lactase. The disaccharidase deficiency can cause cramping and flatulence after the ingestion of carbohydrates, especially milk products.

Which organisms are most commonly associated with diarrhea of less than 2 to 3 weeks’ duration, and what are their clinical characteristics? How are such cases evaluated, and what are the various approaches to treatment?

The evaluation of a case of acute diarrhea involves routine culture of the stools, examination of the stools for the presence of ova and parasites, and, in some instances, flexible sigmoidoscopy.

One of the viral causes of acute diarrhea is the Norwalk agent that is seen in family and community epidemics, usually in older children and adults. It has an incubation period of 1 to 2 days. Vomiting and low-grade fever are common. Rotavirus infection is seen in infants and young children, primarily in winter; the incubation period is 1 to 3 days. Vomiting (occurring in 80%), upper respiratory symptoms, and fever (found in 30%) are common. Enteric adenovirus is a sporadic disease of infants and young children, and is often associated with fever and upper respiratory symptoms.

There are many bacterial causes of acute diarrhea. In Shigella infection, the major site of mucosal invasion is the colon. Penetration of the mucosa and invasion of the bloodstream are rare. Crampy abdominal pain and tenesmus are hallmarks of the disease. The organism produces an enterotoxin (Shiga toxin) that activates adenylate cyclase and causes a watery diarrhea in the early stages of the disease. Bloody diarrhea soon follows. The mainstay of therapy is supportive, with rehydration most important. Narcotics and anticholinergic medications should be avoided. Antibiotic treatment is reserved for those cases that do not resolve spontaneously in several days; ampicillin (500 mg four times a day, orally, for 5 days) is usually effective, but trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (one double-strength tablet twice daily) can be used for resistant strains. Chronic carriers, although uncommon, are prone to intermittent attacks of the disease.

The major site of Salmonella invasion is the ileal and, sometimes, the colonic mucosa. Bacteremia, with or without associated GI symptoms, occurs in approximately 10% of the cases. Carriers are usually asymptomatic, with the organism harbored in the gallbladder. Periumbilical pain and bloody diarrhea last approximately 5 days. Because antimicrobial treatment significantly increases the carrier rate, it is reserved for those cases that do not resolve spontaneously or for those patients who have an underlying predisposing condition.

C. jejuni is a common bacterial pathogen isolated from patients with acute bacillary diarrhea. Invasion of the mucosa occurs predominantly in the colon. Two features that may distinguish C. jejuni infection from other causes of bacterial diarrhea are (a) a prodrome of constitutional symptoms, and (b) a biphasic course, with initial improvement followed by worsening. No antibiotic regimen has been shown to lessen the symptoms or the time course of the disease.

Yersinia enterocolitica can cause enterocolitis, with a clinical picture consisting of fever, abdominal cramping, and bloody diarrhea lasting 1 to 3 weeks. Watery diarrhea is seen, possibly due to enterotoxin production. Invasive ileitis is also a feature of these infections.

Other diarrhea-producing enteric pathogens include E. histolytica, G. lamblia, and Strongyloides stercoralis.

What is the utility of staining stool specimens for leukocytes?

The presence of numerous leukocytes in stool specimens implies the existence of active inflammation of the intestinal mucosa. In cases of acute diarrhea, the presence of pus implies invasion (Shigella, Salmonella, C. jejuni, and E. histolytica). Although Shigella, E. histolytica, and C. jejuni infections are usually associated with most pus, patients with PMC also often have large numbers of fecal leukocytes. In cases of chronic diarrhea, the presence of pus most often implies tuberculosis, amebic colitis, ischemic colitis, or inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis more so than Crohn’s disease, unless the latter involves the colon).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree