Gastric Resection – Subtotal Gastrectomy for Benign Disease

Gastric resection, or gastrectomy, is now performed mainly for treatment of gastric carcinoma. Benign ulcer disease, formerly a major indication, is still sometimes treated by gastrectomy, often in emergency circumstances or neglected cases. Many modifications of the operation exist, differing in the extent of resection and the method of reconstruction of gastrointestinal continuity. This chapter describes basic techniques of gastric resection and reconstruction, primarily as performed for benign disease. The chapter which follows (Chapter 62) describes gastric resection for carcinoma.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified partial gastrectomy as an “ESSENTIAL UNCOMMON” procedure.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE

Subtotal Gastrectomy for Benign Disease

Upper midline incision and thorough abdominal exploration

Identify prepyloric veins of Mayo and evaluate extent of scarring from ulcer disease

Serially clamp, tie, and divide branches of the right gastroepiploic vessels, taking greater omentum from greater curvature

Elevate stomach and divide gastropancreatic folds

Similarly clear an area on the lesser curvature by dividing branches of left gastric artery and vein

Divide stomach with two straight clamps and 4.8-mm linear stapler

Dissect down past pylorus and divide duodenum

For Billroth I Reconstruction

Suture end of duodenum to opening in stomach (two-layer anastomosis)

For Billroth II Reconstruction

Close duodenal stump with staples or sutures

Identify loop of proximal jejunum (20 to 30 cm past ligament of Treitz) and pass antecolic or through hole in transverse mesocolon (retrocolic)

Anastomosis side of loop of jejunum to end of gastric remnant

Close abdomen in the usual fashion without drains

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Injury to common bile duct

Gastric remnant necrosis if splenectomy combined with high ligation of left gastric artery

Retained antrum (dissection not carried down past pylorus and BII performed)

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Esophagus

Stomach

Lesser curvature

Greater curvature

Antrum

Cardioesophageal junction

Pylorus

Duodenum

Ampulla of Vater

Ligament of Treitz

Spleen

Colon

Epiploic appendices

Right Gastric Vein

Prepyloric veins of Mayo

Transverse mesocolon

Greater omentum

Lesser Omentum

Hepatoduodenal ligament

Middle Colic Artery

Marginal artery of Drummond

Pancreas

Accessory pancreatic duct

Common bile duct

Celiac Artery

Common hepatic artery

Proper hepatic artery

Gastroduodenal artery

Right gastroepiploic artery

Left gastric artery

Left gastroepiploic artery

Left gastric vein (coronary vein)

Portal vein

Liver

Left lobe of liver

Triangular ligament of liver

Splenorenal (lienorenal) ligament

Gastrosplenic ligament

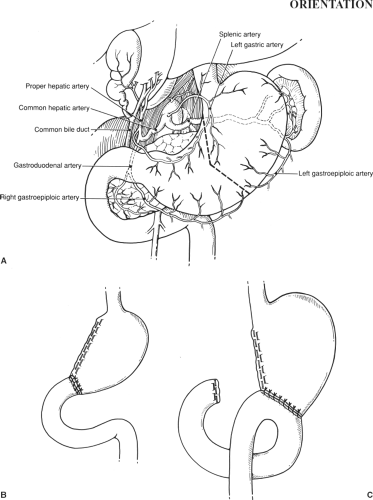

The extent of resection is determined by the pathology. An antrectomy (resection of the antrum of the stomach) is performed for peptic ulcer disease, usually with a concomitant truncal vagotomy. A subtotal gastrectomy involves resection of additional stomach and is generally quantitated according to the approximate amount removed as shown in Figure 61.1A (e.g., a 60% gastrectomy). For radical subtotal gastrectomy, which is performed for carcinoma, resection of the omentum and regional lymph nodes is added (see Chapter 62). Regional lymph nodes lie along the greater and lesser curvatures and along named blood vessels. Total gastrectomy, also generally performed for carcinoma, entails removal of the entire stomach and surrounding node-bearing tissue. The spleen may also be removed during operations for gastric cancer to resect regional lymph nodes in the splenic hilum.

The simplest method of reconstruction after partial gastrectomy is by direct anastomosis of the gastric remnant to the duodenum (Billroth I reconstruction) as shown in Figure 61.1B. This creates what morphologically resembles a small stomach and is applicable when the gastric remnant and the duodenum can be brought together without tension. It is not used in operations for gastric carcinoma because the extent of resection generally precludes it and because recurrent disease can obstruct the new outlet.

The Billroth II reconstruction (Fig. 61.1C) eliminates problems with tension after an extensive resection, as well as the potential for recurrent disease, by closing the duodenal stump and draining the gastric remnant by a gastrojejunal anastomosis. The two limbs of a Billroth II are termed the afferent limb, which drains the duodenal stump, and the efferent limb, through which food exits the stomach into the small intestine. Bile and pancreatic juice from the afferent limb continually pass the stoma and sometimes cause gastritis; the Roux-en-Y reconstruction is designed to surmount this.

In this chapter, partial or subtotal gastrectomy for benign disease is presented first with discussion of the Billroth I and Billroth II methods of reconstruction. Radical subtotal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy are discussed in the chapter which follows (Chapter 62). Less common procedures (rarely performed at present), such as proximal gastric resection, are discussed in the references at the end of the chapter.

Subtotal Gastrectomy

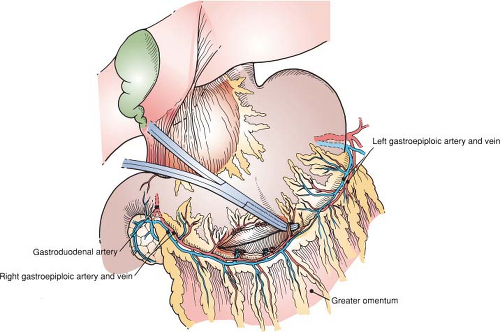

Mobilization of the Greater Curvature (Fig. 61.2)

Technical Points

Enter the abdomen through an upper midline incision and explore it. Note the location of the pylorus by its landmark prepyloric veins of Mayo and determine the extent to which scarring and old or active ulcer disease have altered the anatomy, particularly in the region of the pylorus and duodenum. Verify the position of the nasogastric tube. If a vagotomy is to be performed, do this first (see Figure 65e.1 in Chapter 65e). Then commence mobilizing the stomach by serially dividing and ligating multiple branches of the right gastroepiploic artery and vein running to the greater curvature of the stomach. An opening into the free space of the lesser sac should become apparent. This free space is easier to enter to the left than to the right because multiple filmy layers of omentum can be difficult to separate from the antrum and transverse mesocolon.

Be aware of the close proximity of the transverse mesocolon (and middle colic artery) to gastrocolic omentum, and verify that you are in the correct plane by identifying the transverse mesocolon and pulling it inferiorly. Carry the dissection proximally on the greater curvature to the chosen point of transection of the stomach. The transition point between the left and right gastroepiploic arcades forms an easily recognizable landmark on the greater curvature, corresponding to about a 60% gastric resection.

Continue the dissection distally as far as it will go easily. As the pylorus is reached, chronic inflammation from ulcer disease may render the dissection more difficult. If so, it is best to delay this phase of the dissection until after the stomach is divided proximally. The added mobility will greatly facilitate dissection in the region of the pylorus and duodenum.

Place a Babcock clamp on the distal greater curvature and lift up. Divide multiple avascular adhesions between pancreas and posterior gastric wall with Metzenbaum scissors or electrocautery. A posterior gastric ulcer that is densely adherent to the pancreas is best managed by “buttonholing” the ulcer crater on the pancreas, rather than by attempting excision (which may result in injury to the pancreas).

Figure 61.1 A: Regional anatomy and extent of resection for typical partial gastrectomy. B: Billroth I reconstruction. C: Billroth II reconstruction. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree