Gastric Resection

Gastric resection, or gastrectomy, is performed mainly for treatment of gastric carcinoma. Benign ulcer disease, formerly a major indication, is still sometimes treated by gastrectomy, often in emergency circumstances or neglected cases. Many modifications of the operation exist, differing in the extent of resection and the method of reconstruction of gastrointestinal continuity

Steps in Procedure

Subtotal Gastrectomy for Benign Disease

Upper midline incision and thorough abdominal exploration

Identify prepyloric veins of Mayo and evaluate extent of scarring from ulcer disease

Serially clamp, tie, and divide branches of the right gastroepiploic vessels, taking greater omentum from greater curvature

Elevate stomach and divide gastropancreatic folds

Similarly clear an area on the lesser curvature by dividing branches of left gastric artery and vein

Divide stomach with two straight clamps and 4.8 mm linear stapler

Dissect down past pylorus and divide duodenum

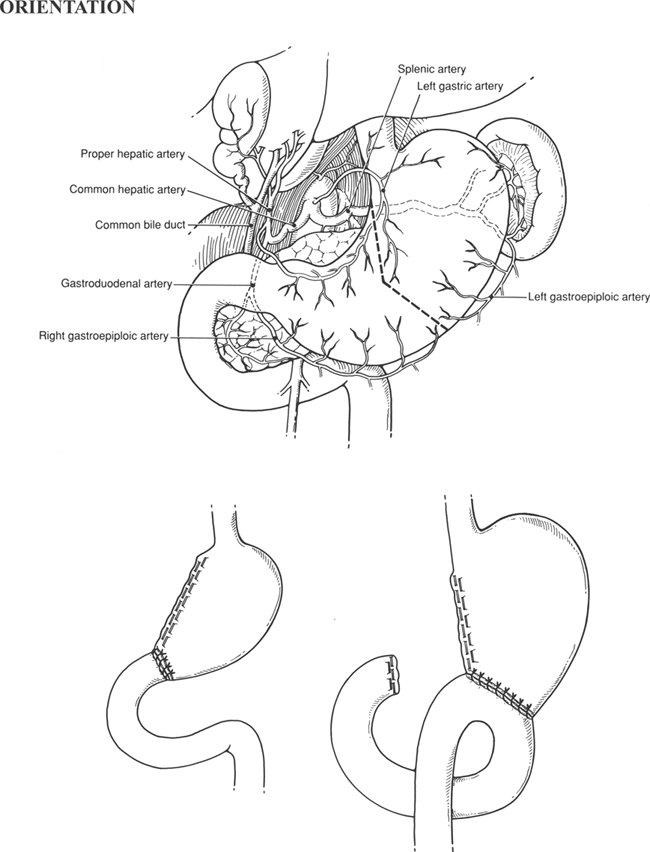

For Billroth I Reconstruction

Suture end of duodenum to opening in stomach (two-layer anastomosis)

For Billroth II Reconstruction

Close duodenal stump with staples or sutures

Identify loop of proximal jejunum (20 to 30 cm past ligament of Treitz) and pass antecolic or through hole in transverse mesocolon (retrocolic)

Anastomosis side of loop of jejunum to end of gastric remnant

Radical Gastrectomy for Carcinoma

Upper midline incision and thorough abdominal exploration

Assess respectability

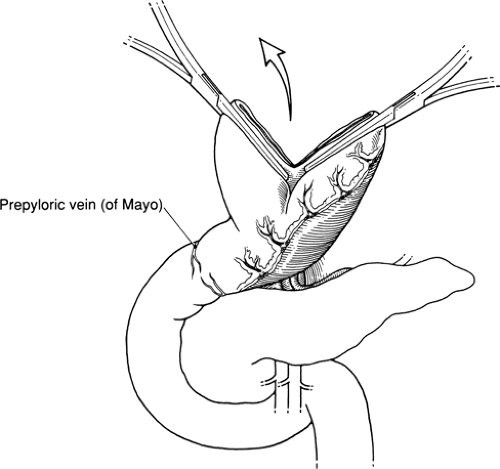

Identify veins of Mayo and divide duodenum with stapler

Flip greater omentum cephalad and detach from transverse colon, preserving mesentery to colon

Elevate stomach and divide left gastric artery at its origin, including perigastric nodes with specimen (D1 resection)

For D2 resection, dissect nodes from celiac axis and hepatoduodenal region

For subtotal resection, divide stomach and perform Billroth II reconstruction as previously described

Total Gastrectomy

Continue dissection to gastroesophageal junction

Divide distal esophagus

Identify loop of proximal jejunum that comfortably reaches to esophagus

End esophagus to side jejunum anastomosis (stapled or sutured)

Inkwell anastomosis or reinforce it

Close abdomen in the usual fashion without drains

Hallmark Anatomic Complications

Injury to common bile duct

Gastric remnant necrosis if splenectomy combined with high ligation of left gastric artery

Retained antrum (dissection not carried down past pylorus and BII performed)

List of Structures

Esophagus

Stomach

Lesser curvature

Greater curvature

Antrum

Cardioesophageal junction

Pylorus

Duodenum

Ampulla of Vater

Ligament of Treitz

Spleen

Colon

Epiploic appendices

Right Gastric Vein

Prepyloric veins of Mayo

Transverse mesocolon

Greater omentum

Lesser Omentum

Hepatoduodenal ligament

Middle Colic Artery

Marginal artery of Drummond

Pancreas

Accessory pancreatic duct

Common bile duct

Celiac Artery

Common hepatic artery

Proper hepatic artery

Gastroduodenal artery

Right gastroepiploic artery

Left gastric artery

Left gastroepiploic artery

Left gastric vein (coronary vein)

Portal vein

Liver

Left lobe of liver

Triangular ligament of liver

Splenorenal (lienorenal) ligament

Gastrosplenic ligament

The extent of resection is determined by the pathology. An antrectomy (resection of the antrum of the stomach) is performed for peptic ulcer disease, usually with a concomitant truncal vagotomy. A subtotal gastrectomy involves resection of additional stomach and is generally quantitated according to the approximate amount removed (e.g., a 60% gastrectomy). For radical subtotal gastrectomy, which is performed for carcinoma, resection of the omentum and regional lymph nodes is added. Regional lymph nodes lie along the greater and lesser curvature and along named blood vessels. Total gastrectomy, also generally performed for carcinoma, entails removal of the entire stomach and surrounding node-bearing tissue. The spleen may also removed during operations for gastric cancer to resect regional lymph nodes in the splenic hilum.

The simplest method of reconstruction after partial gastrectomy is by direct anastomosis of the gastric remnant to the duodenum (Billroth I reconstruction). This creates what morphologically resembles a small stomach and is applicable when the gastric remnant and the duodenum can be brought together without tension. It is not used in operations for gastric carcinoma because the extent of resection generally precludes it and because recurrent disease can obstruct the new outlet.

The Billroth II reconstruction eliminates problems with tension after an extensive resection, as well as the potential for recurrent disease, by closing the duodenal stump and draining the gastric remnant by a gastrojejunal anastomosis. The two limbs of a Billroth II are termed the afferent limb, which drains the duodenal stump, and the efferent limb, through which food exits the stomach into the small intestine. Bile and pancreatic juice from the afferent limb continually pass the stoma and sometimes cause gastritis; the Roux-en-Y reconstruction is designed to surmount this.

In this chapter, partial or subtotal gastrectomy for benign disease is presented first with discussion of the Billroth I and Billroth II methods of reconstruction. Radical subtotal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy are then discussed, and the standard terminology used to describe the extent of resection is briefly explained. Less common procedures (rarely performed at present), such as proximal gastric resection, are discussed in the references at the end of the chapter.

Subtotal Gastrectomy

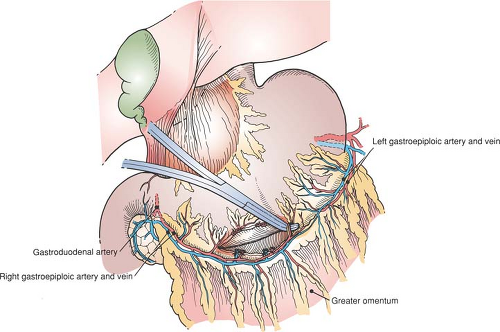

Mobilization of the Greater Curvature (Fig. 53.1)

Technical Points

Enter the abdomen through an upper midline incision and explore it. Note the location of the pylorus by its landmark prepyloric veins of Mayo and determine the extent to which scarring and old or active ulcer disease have altered the anatomy, particularly in the region of the pylorus and duodenum. Verify the position of the nasogastric tube. If a vagotomy is to be performed, do this first (see Fig. 56.1 in Chapter 56). Then commence mobilizing the stomach by serially dividing and ligating multiple branches of the right gastroepiploic artery and vein running to the greater curvature of the stomach. An opening into the free space of the lesser sac should become apparent. This free space is easier to enter to the left than to the right because multiple filmy layers of omentum can be difficult to separate from the antrum and transverse mesocolon.

|

Be aware of the close proximity of the transverse mesocolon (and middle colic artery) to gastrocolic omentum, and verify that you are in the correct plane by identifying the transverse mesocolon and pulling it inferiorly. Carry the dissection proximally on the greater curvature to the chosen point of transection of the stomach. The transition point between the left and right gastroepiploic arcades forms an easily recognizable landmark on the greater curvature, corresponding to about a 60% gastric resection.

Continue the dissection distally as far as it will go easily. As the pylorus is reached, chronic inflammation from ulcer disease may render the dissection more difficult. If so, it is best to delay this phase of the dissection until after the stomach is divided proximally. The added mobility will greatly facilitate dissection in the region of the pylorus and duodenum.

Place a Babcock clamp on the distal greater curvature and lift up. Divide multiple avascular adhesions between pancreas and posterior gastric wall with Metzenbaum scissors or electrocautery. A posterior gastric ulcer that is densely adherent to the pancreas is best managed by “buttonholing” the ulcer crater on the pancreas, rather than by attempting excision (which may result in injury to the pancreas).

Anatomic Points

Although the stomach is predominantly located in the upper left abdomen, the pylorus is inferior to the right seventh sternocostal articulation, typically at the level of the first lumbar vertebra. The prepyloric veins of Mayo are tributaries of the right gastric vein and aid in identification.

The right gastroepiploic artery is a terminal branch of the gastroduodenal artery that usually arises posterior to the first part of the duodenum and to the left of the common bile duct. The position of this artery varies from lying essentially in contact with the stomach to lying as much as 1 cm inferior; gastric branches pass to both anterior and posterior stomach.

A brief description of the development of the greater omentum enables an understanding of the relationship of this structure and of various peritoneal reflections in the upper abdomen. The greater omentum is derived from dorsal mesogastrium. The stomach rotates from its original sagittal orientation to its adult position and becomes more or less transversely disposed and rotated on its long axis. The original left side becomes anterior, and the original right side becomes posterior. The dorsal mesogastrium disproportionately increases in length and drapes anterior to the transverse colon. The portion of the dorsal mesogastrium that is in contact with the posterior parietal peritoneum fuses to it, and the apposed serosal layers degenerate. Dorsal mesogastrium in contact with transverse mesocolon and transverse colon then fuses to these serosal surfaces, and again, apposed serosal surfaces degenerate. Both the anterior and posterior inner serosa of the bursal recess contact each other, fuse, and as before, degenerate. Thus the greater omentum

typically has no cavity, but instead has a bloodless fusion plane between the original anterior and posterior leaves. This leaves the short gastrocolic ligament connecting the greater curvature of the stomach and the transverse mesocolon. Because of the close relationship of the greater curvature of the stomach to the transverse colon, and because the gastrocolic ligament (in which runs the gastroepiploic arcade) and one layer of the transverse mesocolon (in which runs the middle colic artery) are both developmentally related to dorsal mesogastrium, one can expect these arteries to be closely related. The middle colic artery generally passes into the mesocolon at the lower border of the neck of the pancreas, whereas the right gastroepiploic artery arises just superior to the lower border of the first part of the duodenum, slightly to the right of midline. The spatial relationship of the middle colic and right gastroepiploic arteries may, in fact, be functional, because there can be a large anastomotic artery connecting the two.

typically has no cavity, but instead has a bloodless fusion plane between the original anterior and posterior leaves. This leaves the short gastrocolic ligament connecting the greater curvature of the stomach and the transverse mesocolon. Because of the close relationship of the greater curvature of the stomach to the transverse colon, and because the gastrocolic ligament (in which runs the gastroepiploic arcade) and one layer of the transverse mesocolon (in which runs the middle colic artery) are both developmentally related to dorsal mesogastrium, one can expect these arteries to be closely related. The middle colic artery generally passes into the mesocolon at the lower border of the neck of the pancreas, whereas the right gastroepiploic artery arises just superior to the lower border of the first part of the duodenum, slightly to the right of midline. The spatial relationship of the middle colic and right gastroepiploic arteries may, in fact, be functional, because there can be a large anastomotic artery connecting the two.

Texts and atlases invariably depict a gastroepiploic arcade. However, a true anastomosis is absent in 10% of the cases. Typically, when no anastomosis occurs, there is no definitive left gastroepiploic artery; instead, there are several small branches that unite with similar-sized branches of the right gastroepiploic. In the other 90% of cases, the transition between left and right gastroepiploic supply is discerned by the change in angle of origin of the gastric branches.

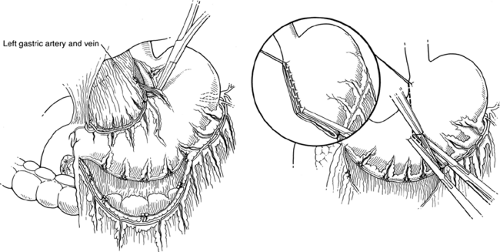

Mobilization of the Lesser Curvature (Fig. 53.2)

Technical Points

Identify the descending branch of the left gastric artery in the lesser omentum. Pass a right-angle clamp under it and double-ligate and divide it. Clean the lesser curvature as high up as desired. Place a 2-0 silk Lembert suture at the upper end of the cleared lesser curvature for traction. Verify the position of the nasogastric tube, high in the gastric pouch and well above the line of proposed transection. Place two Kocher clamps across the greater curvature at the selected point of division and cut between the clamps with a knife. This will form the new outlet of the gastric remnant and should be sized accordingly (about 3 cm, or about the size of the duodenum, for a Billroth I reconstruction, and about 4 to 5 cm for a Billroth II procedure).

Construct a Hofmeister shelf by passing a linear stapling device (with 4.8-mm staples) into the opened crotch of the divided stomach, angling it as high up on the lesser curvature as possible. Use traction on the lesser curvature suture to define the upper extent of resection of the lesser curvature. Fire the stapler and divide the lesser curvature between the stapling device and a Kocher clamp. Check the staple line for bleeding points. Place a moist laparotomy pad over the proximal gastric remnant and allow it to retract into the left upper quadrant, out of the way.

Anatomic Points

The most important vascular structure in the lesser omentum is the left gastric artery. This, the smallest branch of the celiac artery, initially has a retroperitoneal course that runs superiorly and to the left. It then runs anteriorly to approach the gastroesophageal junction. Here, it gives rise to esophageal branches, turns inferiorly to follow the lesser curvature of the stomach, and terminates by anastomosing with the much smaller right gastric artery. Frequently (25% of the time), it gives rise to the left hepatic artery or to accessory left hepatic arteries, which course through the superior part of the lesser omentum. Even

more commonly (42%), it divides into anterior and posterior branches.

more commonly (42%), it divides into anterior and posterior branches.

The right gastric artery is usually a branch of the common or proper hepatic artery, although it frequently arises from the left hepatic or gastroduodenal artery. As with the left gastric artery, it frequently divides into anterior or posterior branches.

Gastric veins parallel the arteries and empty into the portal vein or its components at different levels, rather than as a single vessel. There are no functional valves in these veins, and because the left gastric vein (coronary vein) has free anastomoses with the caval system through the esophageal veins, it assumes great importance in portal hypertension.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree