KEY POINTS

Effective surgical leadership improves patient care.

A fundamental principle of leadership is to provide a vision that people can live up to, thereby providing direction and purpose to the constituency.

Surgical leaders have the willingness to lead through an active and passionate commitment to the vision.

Surgical leaders have the willingness to commit to lifelong learning.

Surgical leaders have the willingness to communicate effectively and resolve conflict.

Surgical leaders must practice effective time management.

Different leadership styles are tools to use based on the team dynamic.

Surgical trainees can be taught leadership principles in formal leadership training programs to enhance their ability to lead.

Mentorship provides wisdom, guidance, and insight essential for the successful development of a surgical leader.

INTRODUCTION

The field of surgery has evolved greatly from its roots, and surgical practice now requires the mastery of modern leadership principles and skills as much as the acquisition of medical knowledge and surgical technique. Historically, surgeons took sole responsibility for their patients and directed proceedings in the operating room with absolute authority, using a command-and-control style of leadership. Modern surgical practice has now evolved from single provider–based care toward a team-based approach, which requires collaborative leadership skills. Surgical care benefits from the collaboration of surgeons, anesthesiologists, internists, radiologists, pathologists, radiation oncologists, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, therapists, hospital staff, and administrators. Occupying a central role on the healthcare team, surgeons1 have the potential to improve patient outcomes, reduce medical errors, and improve patient satisfaction through their leadership of the multidisciplinary team. Thus, in the landscape of modern healthcare systems, it is imperative that surgical training programs include formal instruction on leadership principles and skills to cultivate their trainees’ leadership capabilities.

Many medical and surgical communities, including residency training programs, acknowledge the need for improved physician leadership.2 Surgical trainees identify leadership skills as important, but report themselves as “not competent” or “minimally competent” in this regard.2,3 While a small number of surgical training programs have implemented formal curriculum focused on teaching leadership principles, it is now imperative that all surgical training programs teach these important skills to their trainees.4,5 Interviews of academic chairpersons identified several critical leadership success factors,6 including mastery of visioning, communication, change management, emotional intelligence, team building, business skills, personnel management, and systems thinking. These chairpersons stated that the ability of emotional intelligence was “fundamental to their success and its absence the cause of their failures,” regardless of medical knowledge.6 Thus, training programs need to include leadership training to prepare trainees for success in modern healthcare delivery.

In the United States, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has established six core competencies—patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice (Table 1-1)4—that each contain principles of leadership. The ACGME has mandated the teaching of these core competencies but has not established a formal guide on how to teach the leadership skills described within the core competencies. Therefore, this chapter offers a review of fundamental principles of leadership and an introduction of the concept of a leadership training program for surgical trainees.

CORE COMPETENCY | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

Patient care | To be able to provide compassionate and effective healthcare in the modern-day healthcare environment |

Medical knowledge | To effectively apply current medical knowledge in patient care and to be able to use medical tools (i.e., PubMed) to stay current in medical education |

Practice-based learning and improvement | To critically assimilate and evaluate information in a systematic manner to improve patient care practices |

Interpersonal and communication skills | To demonstrate sufficient communication skills that allow for efficient information exchange in physician-patient interactions and as a member of a healthcare team |

Professionalism | To demonstrate the principles of ethical behavior (i.e., informed consent, patient confidentiality) and integrity that promote the highest level of medical care |

Systems-based practice | To acknowledge and understand that each individual practice is part of a larger healthcare delivery system and to be able to use the system to support patient care |

DEFINITIONS OF LEADERSHIP

Many different definitions of leadership have been described. Former First Lady Rosalynn Carter once observed that, “A leader takes people where they want to go. A great leader takes people where they don’t necessarily want to go, but where they ought to be.” Leadership does not always have to come from a position of authority. Former American president John Quincy Adams stated, “If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more, and become more, you are a leader.” Another definition is that leadership is the process of using social influence to enlist the aid and support of others in a common task.7

FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES OF LEADERSHIP

Clearly, leadership is a complex concept. Surgeons should strive to adopt leadership qualities that provide the best outcomes for their patients, based on the following fundamental principles.

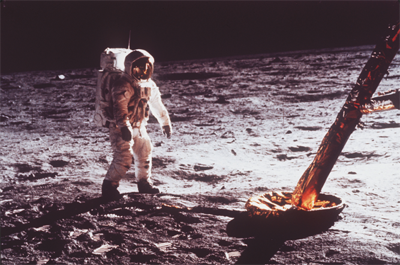

The first and most fundamental principle of leadership is to establish a vision that people can live up to, thus providing direction and purpose to the constituency. Creating a vision is a declaration of the near future that inspires and conjures motivation.8 A classic example of a powerful vision that held effective impact is President Kennedy’s declaration in 1961 that “… this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” Following his declaration of this vision with a timeline to achieve it, the United Sates mounted a remarkable unified effort, and by the end of the decade, Neil Armstrong took his famous walk and the vision had been accomplished (Fig. 1-1).

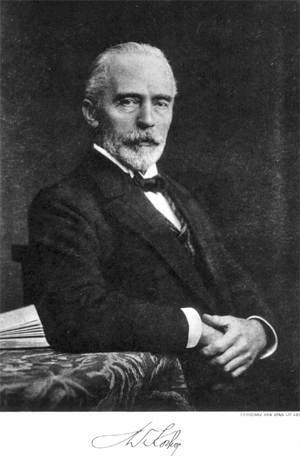

On a daily basis, surgeons are driven by a powerful vision: the vision that our surgical care will improve patients’ lives. The great surgical pioneers, such as Hunter, Lister (Fig. 1-2), Halsted, von Langenbeck, Billroth, Kocher (Fig. 1-3), Carrel, Gibbon, Blalock, Wangensteen, Moore, Rhoads, Huggins, Murray, Kountz, Longmire, Starzl, and DeBakey (Fig. 1-4), each possessed visions that revolutionized the field of surgery. In the nineteenth century, Joseph Lister changed the practice of surgery with his application of Pasteur’s germ theory. He set a young boy’s open compound leg fracture, a condition with a 90% mortality rate at that time, using carbolic acid dressings and aseptic surgical technique. The boy recovered, and Lister gathered nine more patients. His famous publication on the use of aseptic technique introduced the modern era of sterile technique. Emil Theodor Kocher was the first to master the thyroidectomy, thought to be an impossible operation at the time, and went on to perform thousands of thyroidectomies with a mortality of less than 1%. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1909 for describing the thyroid’s physiologic role in metabolism. Michael E. DeBakey’s powerful vision led to the development of numerous groundbreaking procedures that helped pioneer the field of cardiovascular surgery. For example, envisioning an artificial artery for arterial bypass operations, Dr. DeBakey invented the Dacron graft, which has helped millions of patients suffering from vascular disease and enabled the development of endovascular surgery. Dr. Frederick Banting, the youngest recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, had a vision to discover the biochemical link between diabetes and glucose homeostasis. His vision and perseverance led to the discovery of insulin.9 In retrospect, the power and clarity of their visions were remarkable, and their willingness and dedication were inspiring. By studying their careers and accomplishments, surgical trainees can appreciate the potential impact of a well-developed vision.

Leaders must learn to develop visions to provide direction for their team. The vision can be as straightforward as providing quality of care or as lofty as defining a new field of surgery. One can start developing their vision by brainstorming the answers to two simple questions: “Which disease needs to be cured?” and “How can it be cured?”10 The answers represent a vision and should be recorded succinctly in a laboratory notebook or journal. Committing pen to paper enables the surgical trainee to define their vision in a manner that can be shared with others.

The Willingness Principle represents the active commitment of the leader toward their vision. A surgical leader must be willing to lead, commit to lifelong learning, communicate effectively, and resolve conflict.

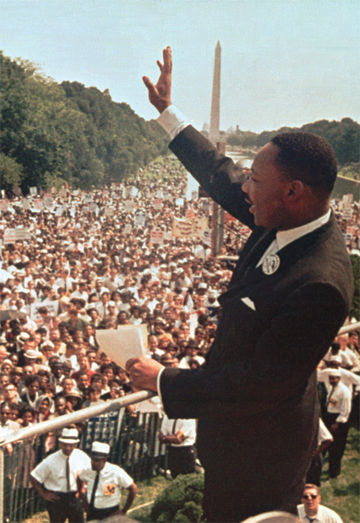

A key characteristic of all great leaders is the willingness to serve as the leader. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who championed the civil rights movement with a powerful vision of equality for all based on a commitment to nonviolent methods,11 did so at a time when his vocalization of this vision ensured harassment, imprisonment, and threats of violence against himself, his colleagues, and his family and friends (Fig. 1-5). King, a young, highly educated pastor, had the security of employment and family, yet was willing to accept enormous responsibility and personal risk and did so in order to lead a nation toward his vision of civil rights, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple Inc., chose to remain in his position as chief executive officer (CEO) to pursue his vision of perfecting the personal computer at great personal expense. He described this experience as “… rough, really rough, the worst time in my life …. I would go to work at 7 a.m. and I’d get back at 9 at night, and the kids would be in bed. And I couldn’t speak, I literally couldn’t, I was so exhausted … . It got close to killing me.”12 Both individuals demonstrated a remarkable tenacity and devotion to their vision.

Willingness to lead is a necessity in any individual who desires to become a surgeon. By entering into the surgical theater, a surgeon accepts the responsibility to care for and operate on patients despite the risks and burdens involved. They do so, believing fully in the improved quality of life that can be achieved. Surgeons must embrace the responsibility of leading surgical teams that care for their patients, as well as leading surgical trainees to become future surgeons. A tremendous sacrifice is required for the opportunity to learn patient care. Surgical trainees accept the hardships of residency with its accompanying steep learning curve, anxiety, long work hours, and time spent away from family and friends. The active, passionate commitment to excellent patient care reflects a natural willingness to lead based on altruism and a sense of duty toward those receiving care. Thus, to ensure delivery of the utmost level of care, surgical trainees should commit to developing and refining leadership skills. These skills include a commitment to lifelong learning, effective communication, and conflict resolution.

Surgeons and surgical trainees, as leaders, must possess willingness to commit to continuous learning. Modern surgery is an ever-changing field with dynamic and evolving healthcare systems and constant scientific discovery and innovation. Basic and translational science relating to surgical care is growing at an exponential rate. The sequencing of the human genome and the enormous advances in molecular biology and signaling pathways are leading to the transformation of personalized medicine and surgery in the twenty-first century (see Chap. 15).13 Performing prophylactic mastectomies with immediate reconstruction for BRCA1 mutations and thyroidectomies with thyroid hormone replacement for RET proto-oncogene mutations are two of many examples of genomic information guiding surgical care. Technologic advances in minimally invasive surgery and robotic surgery as well as electronic records and other information technologies are revolutionizing the craft of surgery. The expansion of minimally invasive and endovascular surgery over the past three decades required surgeons to retrain in new techniques using new skills and equipment. In this short time span, laparoscopy and endovascular operations are now recognized as the standard of care for many surgical diseases, resulting in shorter hospital stay, quicker recovery, and a kinder and gentler manner of practicing surgery. Remarkably, during the last century, the field of surgery has progressed at an exponential pace and will continue to do so with the advent of using genomic analyses to guide personalized surgery, which will transform the field of surgery this century. Therefore, surgical leadership training should emphasize and facilitate the continual pursuit of knowledge.

Fortunately, surgical organizations and societies provide surgeons and surgical trainees a means to acquire new knowledge on a continuous basis. There are numerous local, regional, national, and international meetings of surgical organizations that provide ongoing continuing medical education credits, also required for the renewal of most medical licenses. The American Board of Surgery requires all surgeons to complete meaningful continuing medical education to maintain certification.14 These societies and regulatory bodies enable surgeons and surgical trainees to commit to continual learning, and ensure their competence in a dynamic and rapidly growing field.

Surgeons and trainees now benefit from the rapid expansion of web-based education as well as mobile handheld technology. These are powerful tools to minimize nonproductive time in the hospital and make learning and reinforcement of medical knowledge accessible. Currently web-based resources provide quick access to a vast collection of surgical texts, literature, and surgical videos. Surgeons and trainees dedicated to continual learning should be well versed in the utilization of these information technologies to maximize their education. The next evolution of electronic surgical educational materials will likely include simulation training similar to laparoscopic and Da Vinci device training modules. The ACGME, acknowledging the importance of lifelong learning skills and modernization of information delivery and access methods, has included them as program requirements for residency accreditation.

The complexity of modern healthcare delivery systems requires a higher level and collaborative style of communication. Effective communication directly impacts patient care. In 2000, the U.S. Institute of Medicine published a work titled, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which raised awareness concerning the magnitude of medical errors. This work showcased medical errors as the eighth leading cause of death in the United States with an estimated 100,000 deaths annually.15 Subsequent studies examining medical errors have identified communication errors as one of the most common causes of medical error.16,17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree