Free Transverse Rectus Abdominis Musculocutaneous Flap Reconstruction after Mastectomy

Maurice Y. Nahabedian

Ketan M. Patel

DEFINITION

Breast reconstruction using free tissue transfer techniques have become routine procedures following mastectomy.

The most common free flaps for breast reconstruction include the free transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous (TRAM) flap and the deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap. Indications for these flaps are primarily based on the availability of sufficient skin and fat at the abdominal donor site.

There are several decision points to be considered when determining candidacy for a free TRAM or DIEP flap. Many patients are now choosing to have bilateral mastectomy and reconstruction in the setting of unilateral breast cancer or for prevention of breast cancer.

Once the decision to proceed with an abdominal free flap for breast reconstruction has been made, decisions relating to the type of abdominal flaps are considered and based on patient anatomy and surgical experience.

Non-muscle-sparing free TRAM flaps are technically easier but are associated with increased donor site morbidity that includes contour abnormalities and weakness. These morbidities are increased when the continuity of the rectus abdominis muscle has been disrupted, such as with the traditional pedicle TRAM and the MS-0 (full width) free TRAM. For these reasons, the full-width free TRAM flap is rarely performed and will not be included in this review.

Muscle-sparing free TRAM flaps and DIEP flaps are technically more challenging and require a better understanding and appreciation of perforator anatomy and dissection techniques. This chapter will focus on the free TRAM flap, whereas the DIEP flap is covered in Part 5, Chapter 19.

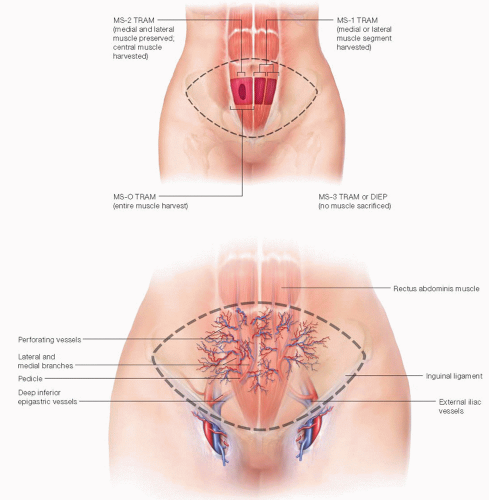

MS-0: no muscle preservation (traditional TRAM flap)

MS-1: medial or lateral muscle preservation

MS-2: medial and lateral muscle preservation (central muscle sacrificed)

MS-3: total muscle preservation (DIEP flap)

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Many women with moderate to excessive volume are interested in these options because of the abdominoplasty appearance of the abdomen that is usually obtained.

In women that lack a suitable quantity of abdominal soft tissue, alternative donor site options such as the gluteal or medial thigh region are considered.

Sufficient donor site volume must be assessed to deliver appropriate breast volume. In some cases of bilateral free flap reconstruction, a hemiabdominal flap may not provide adequate volume and adjuncts such as combining flaps with implants or autologous fat grafting may warrant consideration.

Prior abdominal surgery or body habitus may necessitate the use of computerized tomographic angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) to assess the patency and location of the perforators and deep inferior epigastric artery and vein.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

A thorough history should focus on comorbidities, smoking history, previous surgeries, and medications that can alter surgical management and affect microvascular reconstruction. (Examples include coagulopathies, previous cardiac bypass surgery, previous abdominal surgery, and antiplatelet medications.)

Physical exam will uncover hernias and previous abdominal scars. In addition, an assessment of the anterior abdomen for thickness and dimensions will aid in estimating a reconstructed breast volume.

General complications include bleeding, hematoma, seroma, infection, delayed healing, and injury to surrounding structures.

Specific complications include a 1% to 3% total flap failure rate,2 early revisional surgery for microsurgical anastomotic thrombosis, late revisional surgery for contour irregularities, breast asymmetry, poor cosmetic result, and donor site complications that include an abdominal bulge/hernia (3% to 5%),3 complex scarring, lateral “dog ears,” and prolonged pain.

Average length of surgery can range from 4 to 8 hours for a unilateral reconstruction and 6 to 12 hours for a bilateral reconstruction. Appropriate deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis and perioperative antibiotics are routinely used due to the length and extent of surgery.

The decision to proceed with a free TRAM or DIEP flap is sometimes made preoperatively and other times intraoperatively. Patients with a high body mass index (BMI) (>35) who have an overriding pannus are usually scheduled preoperatively for a muscle-sparing free TRAM flap. In other patients, who are found to lack a dominant perforator intraoperatively, the decision to convert from a DIEP to a free TRAM is made. If one or two dominant perforators are found, a DIEP flap is performed.

Anatomy

The lower abdominal skin is supplied by perforating vessels from the primary source vessels that include the superior and deep inferior epigastric system.

Source vessels travel vertically along the fibers of the rectus abdominis muscle on each side of the abdomen and send vertical perforating vessels to the overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue.

The inferior epigastric system originates from the medial aspect of the external iliac system just superior to the inguinal ligament. The pedicle enters the rectus abdominis muscle on the undersurface from the inferolateral aspect of the muscle at the junction of the lateral and central third of the muscle.

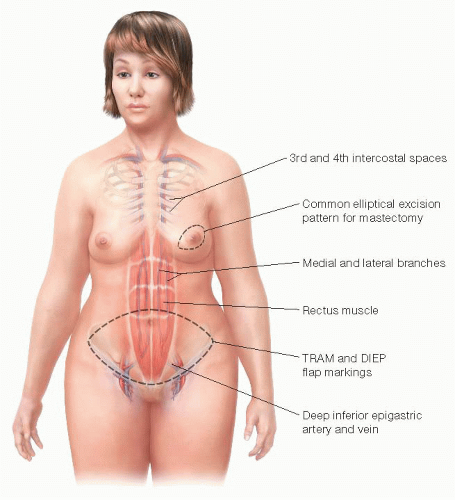

Two main intramuscular branches are identified: a lateral and medial branch. These branches then send perforating vessels to the overlying skin (FIG 1 [bottom]).

TECHNIQUES

ABDOMINAL FLAP HARVEST

The patient is marked in the upright position (FIG 2). The anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) is palpated and marked bilaterally. The upper extent of the abdominal flap is delineated, connecting the two ASIS marks across the abdomen and staying approximately 1 cm above the umbilicus. The lower abdominal line is an estimation that extends from the two ASIS markings in a curvilinear fashion. The inferior limit of this line is the pubic symphysis. The final inferior line is determined in the operating room after the upper skin flap is redraped. The markings for a free TRAM flap and a DIEP flap are identical (FIG 3).

The initial incision is the upper abdominal ellipse. The incision extends to the anterior rectus sheath using electrocautery (FIG 4). The upper abdominal adipocutaneous flap is typically undermined to the midpoint between the umbilicus and the xiphoid process.

The patient is flexed 10 to 30 degrees and the lower abdominal ellipse is definitively delineated and incised. The umbilicus is incised and preserved on its stalk.

Flap elevation begins from a lateral to medial direction at the level of the anterior rectus sheath. The “safe zone” extends to the lateral edge of the linea semilunaris. Medial to the linea semilunaris, extreme precautions are taken to preserve and avoid injury to perforating vessels from the deep inferior epigastric system (FIG 5).

A decision at this stage must be made to determine if a muscle-sparing free TRAM flap or DIEP flap will be performed. In either case, the lateral innervation to the rectus abdominis muscle is preserved.

If bilateral free DIEP flaps are to be performed, medial to lateral and lateral to medial perforator dissection is performed (FIG 6). This is facilitated using bipolar cautery or monopolar cautery at very low current. Mosquito clamps are used to elevate and divide strands of muscle fibers without injury to the perforators or underlying vasculature.

With the muscle-sparing free TRAM technique, an island of perforators is defined and the anterior rectus sheath surrounding the island of perforators is incised (FIG 7).

The medial and lateral sheath is elevated off the muscle and the retrorectus space is defined. The surrounding muscle is divided using monopolar or bipolar cautery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree