|

Carotid Body Tumor |

Jugulotympanic |

Retroperitoneal Intra-abdominal |

Cauda Equina/Filum Terminale |

Synonyms |

Chemodectoma, nonchromaffin paraganglioma |

Glomus tumor, glomus jugulare, glomus tympanicum |

Extra-adrenal paraganglioma |

– |

Location |

Neck, at the bifurcation of the carotid artery; localized deep to the anterior border of sternocleidomastoid muscle, just below the angle of mandible; may be attached to the arteries or even encase them |

Middle ear, external meatus 85%, parapharyngeal space, base of the skull; intracranial extension possible |

Along the sympathetic trunk; commonly in retroperitoneum; can arise from organs of Zuckerkandl visceral involving urinary bladder, gall bladder |

Intradural, or extradural; attached to filum terminale or a nerve root |

Incidence |

85% of head and neck paragangliomas |

Most common tumor of the middle ear |

90% associated with sympathetic nervous system |

Very uncommon |

Average age |

Wide age range but common in fifth decade |

Fifth decade |

Third to fifth decade |

Third to fifth decade |

Gender predilection |

None; but common in females at higher altitude |

Common in females; M:F, 1:5 |

None |

Slight increase in males |

Radiologic findings |

Homogeneous hypervascular, well-delineated mass lesion at the carotid artery bifurcation by carotid arteriogram |

Soft tissue mass; bone erosion |

Mass on CT scan |

Mass on CT scan, MRI, blockage on myelogram |

Association with other paragangliomas and syndromes |

May be associated with jugulotympanic paragangliomas, a part of Carney triad (GIST, pulmonary chondroma, and carotid body tumor); may be associated with pheochromocytoma, or MEN syndrome |

May be associated with carotid body paraganglioma; can be part of familial multifocal head and neck paragangliomas as an autosomal dominant trait |

None |

None |

Presenting symptoms |

Painless, slowly enlarging neck mass, located below the angle of the mandible; deep to the anterior border of sternocleidomastoid muscle; vertically fixed but movable horizontally; may be pulsatile |

Tinnitus; aural pulsations; conduction-type hearing loss; ear fullness; pain; otorrhea; vertigo; dizziness; facial palsy; bulging of tympanic membrane; tumor may fill the middleear cavity and extend into external auditory canal or extend into cranial cavity |

Back pain; palpable mass; symptoms due to secretion of norepinephrine |

Lower back pain, radicular pain or sciatica is common; sensory-motor deficits include paraplegia and sphincter disturbances |

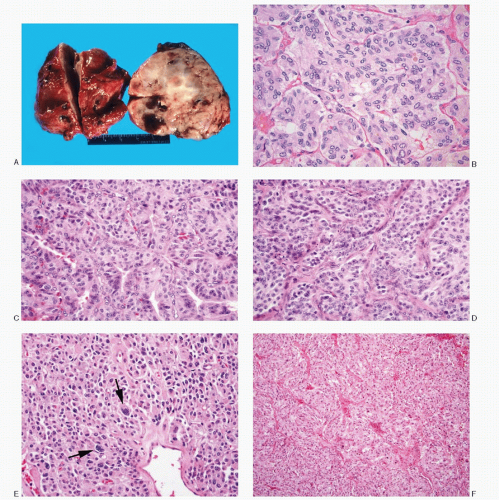

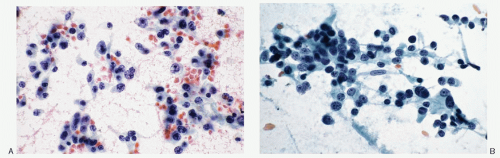

Gross pathology |

Encapsulated, well circumscribed; ovoid, rubbery to firm; redpink to tan-gray |

Polypoid, red fragile mass; bleed profusely to touch |

3-20 cm; well-defined mass, solid cut surface; hemorrhage and cystic change frequent; usually solitary |

Generally egg shaped or sausage shaped; encapsulated; dark red, attached to filum terminale or a nerve root; size 2-4 cm |

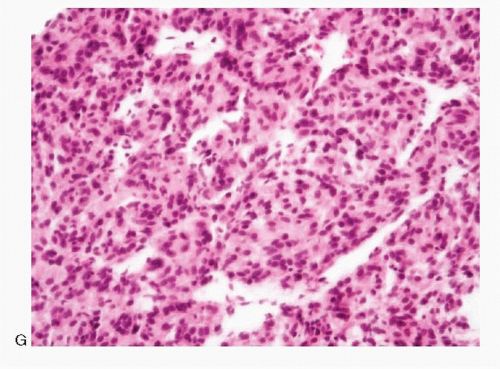

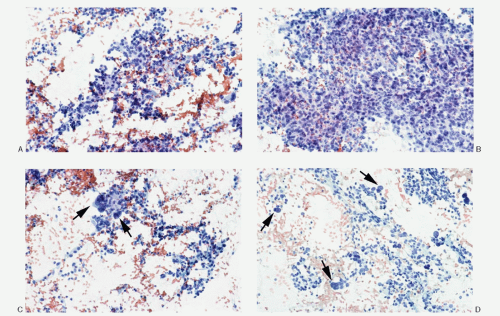

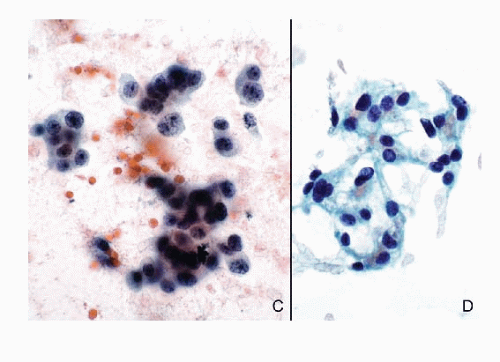

Histology |

Typical alveolar or nesting pattern (Zellballen); can be trabecular, or solid with diffuse growth pattern; monomorphic to pleomorphic; scant stroma |

Typical nesting pattern; may show marked stromal fibrosis, lacking the typical pattern |

Typical alveolar or nesting pattern (Zellballen); can be trabecular, or solid with diffuse growth pattern; monomorphic to pleomorphic; scant stroma; prominent vascularity; no attached remnants of adrenal tissue |

Typical alveolar or nesting pattern or solid growth pattern; ganglionic differentiation frequent; may express cytokeratin |

Differential diagnoses |

Medullary thyroid carcinoma

Malignant melanoma

Alveolar soft-part sarcoma

Malignant lymphoma

Metastatic carcinoma |

Hemangiopericytoma

Pituitary adenoma

Meningioma, small cell type

Malignant lymphoma

Plasmacytoma

Olfactory neuroblastoma

Middle ear adenoma |

Adrenocortical carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma

Malignant melanoma

Malignant lymphoma

Soft tissue tumors |

Hemangiopericytoma

Ependymoma

Chondrosarcoma

Malignant lymphoma

Plasmacytoma

Meningioma |

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access