Exposure and Open Surgical Management at the Diaphragm

Peter H. U. Lee

Ramin E. Beygui

DEFINITION

Thoracoabdominal aneurysms and complicated descending aortic dissections are the two most likely reasons for requiring surgical exposure of the diaphragm in vascular surgery. The need to expose the aorta both above and below the diaphragm requires an extended incision spanning the left thorax to the abdomen, the length and exact location of which depends on the location of the targeted aortic pathology. Often, the diaphragm must be divided, necessitating an awareness of the regional anatomy as well as various surgical management considerations.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

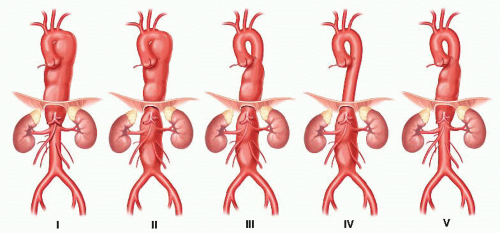

Thoracoabdominal aneurysm: The Crawford classification categorizes thoracoabdominal aneurysms according to the extent of the aneurysm and is the most widely used1 (FIG 1). The classification is as follows: type I, from the left subclavian artery to just above the renal arteries; type II, from the left subclavian artery to the infrarenal aorta; type III, from the mid-descending thoracic aorta to below the renal arteries; type IV, from the diaphragmatic aorta to the iliac bifurcation; and type V (modified classification by Safi et al.2): from the mid-descending thoracic aorta.

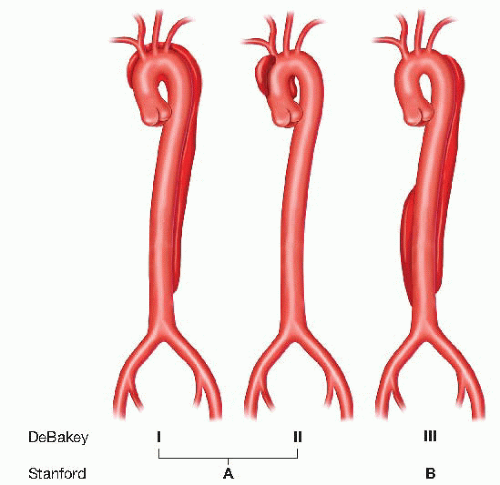

Descending (type B) aortic dissection: Two classifications systems are commonly used to describe the extent of aortic dissections (FIG 2). Stanford type A dissections involve the ascending aorta with or without involving the descending aorta, whereas type B dissections only involve the descending aorta beyond the left subclavian artery. The DeBakey classification includes type I, which involves both the ascending and descending aortas; type II, which involves only the ascending aorta; and type III, which involves only the descending aorta.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Most patients who are referred for surgery for a thoracoabdominal aneurysm present with no symptoms. However, when they do have signs and/or symptoms, they may present with pain in the chest, abdomen, or lower back; a mass in the abdomen, which may be pulsatile, or rigid abdomen; and evidence of atheroembolism distally. The aforementioned symptoms, with signs of hypovolemic shock, may indicate a ruptured aneurysm.

Uncomplicated descending aortic dissections are generally managed medically. However, if the dissection is complicated, such as when it is associated with significant symptoms or leads to visceral or distal malperfusion, rapid surgical intervention is warranted.

A more complete discussion regarding indications for intervention in aortic dissections and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm can be found in a number of relevant reference textbooks.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Imaging is used to determine the proximal and distal extent of repair required. It impacts the type of exposure required (i.e., thoracotomy vs. laparotomy vs. thoracoabdominal incision) as well as the level of incision.

If the exposure is for the repair of thoracoabdominal aortic pathology, all patients require adequate preoperative imaging, ideally consisting of a computed tomography aortography (CTA) with or without 3-D reconstruction. Magnetic resonance aortography (MRA) may also provide the necessary information, but this generally requires more time, is more expensive, and requires more extensive postprocessing. However, MRA is the study of choice when CTA is contraindicated or unsafe, such as in patients with a contrast allergy or renal insufficiency. Catheter-based invasive aortography has generally been supplanted by CTA and MRA as the primary preoperative imaging

modality of choice, as it is more cumbersome and does not provide a complete assessment of the aneurysm, including thrombus volume and adjacent anatomic structures.

If the surgery is elective, as in the case of an incidentally found aneurysm, extensive preoperative evaluations are necessary to minimize postoperative morbidity and mortality.

Thorough evaluations of the cardiac, pulmonary, and renal systems are necessary, especially because these systems are most commonly affected when there are complications. Depending on the risk factors and prior history, further testing may be required and patients should be referred to appropriate specialists for proper evaluation. A good neurologic evaluation is also warranted, particularly if the patient has a prior history or symptoms suggestive of a lower extremity weakness or spinal injury.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT Preoperative Planning

Determine the possible need for adjuncts such as cardiopulmonary bypass and neurophysiologic monitoring. In some instances, pulmonary artery catheters may be warranted for monitoring cardiovascular hemodynamics.

Assess the need for spinal cord protection, including the use of lumbar drainage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), distal aortic perfusion, epidural cooling, and distal aortic perfusion.

Given the expected amount of blood loss, a Cell Saver and rapid infuser should be available.

Double lumen endotracheal tube should be used for singlelung ventilation of the right lung. Bronchial blockers are not reliable adjuncts for this purpose.

Positioning

Initially, place the patient supine on a deflated beanbag (FIG 3). Roll the left chest upward and toward the right and place a shoulder roll under the right axilla and a bump under the left scapula while also gently pulling and securing the right arm over to the right side. Ideally, the upper back should be rotated about 60 degrees to the table with the pelvis remaining flat, such that the trunk is twisted to the right. Position the patient with the break located halfway between the left costal margin and the left iliac crest. Jackknife the table and then inflate the beanbag. Be sure to support and secure the arms (“airplane” splint for the left arm) and pad all pressure points on the body and extremities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree