Exercises and Educational Courses in Terrorism Preparedness

Myra M. Socher

Edwin K. Leap

INTRODUCTION

Very few emergency care workers have ever cared for the casualties of weapons of mass destruction. Terrorism, which is an enormous concern for all health care providers and emergency responders, is still relatively rare when held up against the background of our normal practices and concerns. That is, it is rare so far. But the world is a dangerous place, and the war on terror is in its infancy.

If we want to be prepared, we have roughly three options. We can turn away from all of the bad news and pretend, if we try hard enough, that it will never happen to us. Statistically, we may be right. The majority of persons in industrialized nations currently do not live in areas that are considered high risks for terrorist use of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). This approach has some undeniable practicality. A physician or paramedic may spend 30 years in practice and never see a case of weaponized plague, or care for a patient with radiation sickness. But then again, we could make the same argument for many of the problems we encounter in caring for the health needs of the public. We could say, for instance, that physicians in the rural South do not need to know about HIV if it is rare where they work. We could say that paramedics in ski areas need not learn to deliver babies because what are the odds? But this is a risky way to play the numbers, and the results can be disastrous if our assessment of the risks turns out to be wrong. A little preparation, a little knowledge, just enough to recognize a problem and call for help, might save one life or thousands. So, ignoring the risk of terrorism may not be the best plan.

As a second alternative, we could go to the opposite extreme and seek to be exposed to terrorist events and mass casualty episodes. We could, if we have not already, join the military and travel to combat zones, just to get a feel for the danger, the heightened alertness, the sound of gunfire, and the look of exploded vehicles. There we would learn first-hand how to care for victims of bombs or bullets and learn, through our own wish to survive, how to be vigilant for signs of chemical, biological, and radiological illnesses. Or perhaps, we could work at a large urban emergency department.

If ignoring the problem is unacceptable, and if seeking it out is impractical, then we must obtain the knowledge and training by attending educational courses and exercises in terrorism preparedness.

Most emergency care workers have at least a little experience with preparedness exercises. Some of our more “seasoned” colleagues still remember the days of “duck and cover,” when an entire nation practiced, to greater or lesser extents, what they would do in the case of nuclear war. In those days, the Civil Defense initiative existed because the world moved through its days and nights with the very real fear that nuclear weapons would fall like rain one day.

It was a fear with legitimate foundations, based on the very real existence of intercontinental ballistic missles (ICBMs) in silos and submarines around the world, possessed by the two most powerful military forces in the world, which were run by governments with philosophies diametrically opposed to one another. Whether anyone believed it would matter or not, they practiced the old duck-and-cover drill because doing something was better than doing nothing. The Cold War, which was covert and conducted mostly by spies and diplomats, was considered by some as the equivalent of World War III. If this is correct, then the advent of the recent major terrorist attacks is the equivalent of a fourth world war.

It was a fear with legitimate foundations, based on the very real existence of intercontinental ballistic missles (ICBMs) in silos and submarines around the world, possessed by the two most powerful military forces in the world, which were run by governments with philosophies diametrically opposed to one another. Whether anyone believed it would matter or not, they practiced the old duck-and-cover drill because doing something was better than doing nothing. The Cold War, which was covert and conducted mostly by spies and diplomats, was considered by some as the equivalent of World War III. If this is correct, then the advent of the recent major terrorist attacks is the equivalent of a fourth world war.

Most emergency workers have also had some experience with disaster drills. Medical schools and hospitals have traditionally held annual exercises that involve situations like tornadoes, earthquakes, plane crashes, and industrial accidents. These exercises are often attended by emergency department staff, EMS workers, residents, and students. Other hospital personnel, including administrators and health practitioners from nonemergency settings, often elect not to participate in these exercises.

It may be argued that the modern era has brought us a reality even more terrifying than the ICBMs, which dominated our attention in the Cold War. Nuclear missiles, for all of their potential apocalyptic power, were possessed by nations whose leaders and citizens generally wanted to see their grandchildren. And they were generally secured and maintained by large disciplined military forces. The modern threat of terror and weapons of mass destruction is quite different from those days. In terrorism, hatred combines with technology, and suicidal fervor combines with tremendous lethality. The result is that even the most jaded and cynical emergency care provider recognizes that “it could happen here.” And since it could, preparation is essential.

Because of a number of widely publicized terrorist events in the 1990s, emergency care providers in the United States have made an enormous effort to prepare for the prospect of terrorism on American soil. This effort, like all great efforts, has been a combined labor. It involves all levels of health care, federal government, as well as the emergency providers in the field. We begin this chapter by describing the Domestic Preparedness (DP) training program, as a very positive example of how training has been taken to the population centers of the United States. Federal legislation that used resources and information from diverse and capable organizations in the government and private sectors was enacted, and then all of those assets were pooled into this program, which was disseminated to municipalities across the country.

If the essence of the program could be summarized, it would be in the phrase “NBC Delta,” which is the concept at the heart of this training system. It means that, although the nation is well prepared for many emergency contingencies, there is a gap between existing preparation and the preparation needed for response to nuclear, biological, and chemical agents or weapons of mass destruction. The delta, or difference, was the critical gap that the Domestic Preparedness program sought to fill.

The program began in 1996, one year after the attack on Oklahoma City, and five years before the attack on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon. It might be said that the DP program was both reactionary and visionary. Those who conceived and implemented it sensed a growing danger to the United States and acted on their intuition. Although most of those involved in running the DP program did not foresee the use of an airliner as a weapon of mass destruction, the DP program had already laid the initial framework that allowed the country to augment its response faster, and more effectively, in the weeks, months, and years since 9/11. The original program targeted the largest 120 cities and used a “train-the-trainer” format. It was thought that by preparing instructors across the nation, the effect of terrorism preparedness education would be multiplied. This program continues, now under the direction of the Office for Domestic Preparedness, within the Department of Homeland Security. It has evolved into a program with multiple course topics and multiple levels of training. It continues to provide an outstanding level of preparedness training for a nation that remains under the constant threat of terrorism.

However, preparedness training did not stop there. Humans are very creative creatures, and so we always try to reinvent, always try to improve. Some of the improvements in preparedness training we now see include self-assessments for organizations and individuals to take before training and open table-top exercises that are less intimidating and more entertaining than traditional didactics. Furthermore, because emergency responders and health care providers are not always able to travel long distances to receive training, the training is being taken to them. The Internet is a growing source of distance education in WMD preparedness issues; it also contains an enormous amount of accessible information that can be useful in real time, or as some have described it, “just in time,” by those faced with possible WMD events, whether suspicious infectious outbreaks or dramatic chemical exposures.

This chapter is included in the text so that readers can have some perspective on preparedness exercises and education in weapons of mass destruction, as well as some insight into the new directions that preparedness training is taking. It is useful to review the progress that such training has taken. As we look at how training was conducted in the past, we can respond to current threats more easily. And as we assess what has been successful, we can make future courses and exercises more effective. It is the least we can do for the emergency responders and health care workers who will use them as they prepare to safeguard our nation against the terrifying, unthinkable, but all too real threat of terrorist use of weapons of mass destruction.

PREPAREDNESS ESSENTIALS

Preparedness is a continuum, with no real endpoint. We are better prepared today than we were yesterday, and tomorrow we will be even more prepared. If we try to define preparedness we can say that “it is a proactive effort by an institution to shift rapidly from a normal and routine state to a heightened state of alert and an increased level of operations in response to a disaster or a multiple casualty incident” (1). Although we can never be totally prepared for every eventuality, through education, planning, and exercises, we can progress to more advanced levels of preparedness.

Perhaps the most important element of preparedness is awareness. When students are aware of existing and potential threats, they will be better motivated and better able to deal with an act of terrorism. In light of their awareness, they can learn how to evaluate their current response systems and existing policies and procedures. Using their newly acquired knowledge, they will be able to “harden” their institution’s ability to respond to an incident.

Preparedness is the result of planning, but even a good plan is only useful if it is exercised and the results of the exercise are used to improve its structure. Many valuable planning templates, from hospitals to Metropolitan Medical Response Systems, are available at the micro and macro levels. Geographically, efforts extend from local and regional efforts to programs conducted by federal agencies (e.g., CDC’s Pandemic Influenza Plan) (2). Medical planners are encouraged to take advantage of these.

Emergency operations plans (EOPs) provide the roadmap to a response effort. They provide detailed instructions on how to navigate the obstacles that arise, how to manage the sudden influx of patients into the health care system, how to provide for their physical and mental well-being, and how to recover from an incident and return to normal day-to-day operations as quickly and efficiently as possible. Training is needed to incorporate these EOPs properly into the response plan (3).

Education follows planning. There are many different programs that use diverse media in both the public and private sectors, and educators must choose wisely when selecting the programs that are best suited to their particular audiences.

There is a trend to move away from the more traditional didactic courses to facilitated workshops, table-top exercises, and larger field exercises. Case-based teaching has increased in popularity in many so-called merit badge courses such as Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), and this trend is being translated to WMD training.

Exercises constitute an important component of any training program. “Experience and data show that exercises are a practical and efficient way to prepare for crises. They test critical resistance, identify procedural difficulties, and provide a plan for corrective actions” (4).

After any exercises or other case-based educational program, a session is typically conducted between the course moderators and the regional and local leaders, and a summary of the major suggestions and comments is prepared for distribution to all participants. This after action report provides an opportunity to receive input for improving the course content and to discuss application to the specific environment where the program was conducted. Major exercises in the United States deserve special discussion. The first of these was called TOPOFF (Top Officials) 2000, conducted in May of that year. It was a congressionally mandated, no-notice exercise that was staged at three locations and that simulated radiological, chemical, and biological attacks. After action reports provided valuable feedback, and the lessons learned were incorporated into the design of TOPOFF II.

TOPOFF II, also congressionally-mandated, was preceded by a series of WMD seminars and table-top exercises designed to educate the participants prior to the actual exercise. An “open exercise design” was used, where stakeholder participants worked in concert with exercise design experts to develop the program. The organizers considered the use of this technique a success. They cited enhanced learning by the participants due to their direct participation in the development of the exercise (5). It was also described as having allowed regional planners to “develop and strengthen relationships in the national response community.”

Of significance to the medical community was the simulated public health emergency in Illinois, one of the largest mass casualty exercises to date, which examined the coordination between the medical and public health communities, and their ability to respond to and intervene in the spread of the epidemic. A significant finding, in keeping with the results of most, if not all, exercises was the lack of an effective communications system. Additionally, they described casualties among health care providers, a well-known factor in areas where terrorist bombings often involve a second device targeting responders.

More recently, a secret cabinet-level table-top exercise called Scarlet Cloud (anthrax), “showed that we are a lot better off today than we were two years ago before 9/11,” according to a senior administration official. “It also showed that there has definitely been a fast learning curve on bioterrorism” (5)

Exercises provide an excellent tool to identify, analyze, and quantify the strengths and gaps in our response systems and our degree of understanding of WMD and its accompanying threats. So, we should use exercises of varying degrees of sophistication, duration, and intensity as an integral part of any education process.

PREPAREDNESS HISTORIC EVENTS AND CASE HISTORIES

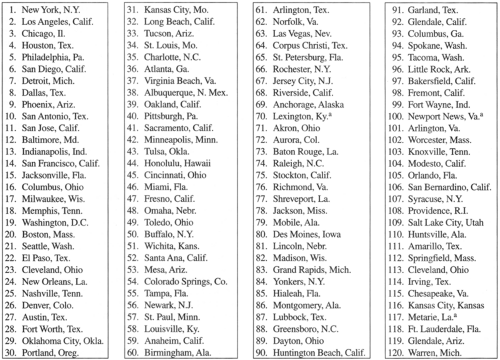

In the early- to mid-1990s, several notable terrorist events had a great impact on planning for potential threats in the United States. The bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993, the terrorist chemical attack on the Tokyo subway system in 1995, the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995, and the Centennial Park bombing in Atlanta in 1996 led to the passing of legislation to better equip our nation’s first responders (6). The Nunn-Lugar-Domenici (NLD) Defense against Weapons of Mass Destruction Act of 1996 (Public Law 104-201) mandated training for the 120 most populous cities in the United States (Fig. 33-1) (7).

The resultant Domestic Preparedness (DP) program provided the initial benchmark training for the medical response to terrorism for federal, state, and local agencies and is considered the prototype on which many other courses were built. This training was designed for federal, state, and local emergency responders to prepare for possible terrorist incidents involving Nuclear, Biological and Chemical (NBC) agents (8).

In February 1997 the Department of Defense’s U.S. Army Chemical and Biological Defense Command (CBDCOM), now the Soldier and Biological Chemical Command (SBCCOM), took the lead with the support of five other federal agencies (Department of Energy, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Federal Emergency Management Agency, U.S. Public Health Service, and the Environmental Protection

Agency) to develop the DP program. They conducted four focus group meetings with first responders to determine core competencies and to develop comprehensive training performance objectives. Firefighters, hazardous materials (hazmat) specialists, on-scene incident commanders, emergency medical services, physicians, law enforcement officers, and 911 operators and call takers, as well as the appropriate federal agencies participated in this effort. The findings and recommendations of these focus groups formed the basis for a comprehensive set of 26 training performance objectives, details of which may be found in the matrix in Table 33-1 (9).

Agency) to develop the DP program. They conducted four focus group meetings with first responders to determine core competencies and to develop comprehensive training performance objectives. Firefighters, hazardous materials (hazmat) specialists, on-scene incident commanders, emergency medical services, physicians, law enforcement officers, and 911 operators and call takers, as well as the appropriate federal agencies participated in this effort. The findings and recommendations of these focus groups formed the basis for a comprehensive set of 26 training performance objectives, details of which may be found in the matrix in Table 33-1 (9).

Figure 33-1. Cities selected for Domestic Preparedness program (in order of population). aNot a city government. (Source: US Army Chemical and Biological Defense command.) |

The performance objectives considered existing emergency response guidelines and standards prescribed by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), and the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO). They were structured according to four competency levels (Awareness, Operations, Technician/Specialist [nonmedical and medical response], and Incident Command) with three separate levels of training (Basic, Advanced, and Specialized). These competencies reflected the levels identified in OSHA’s 29 code of federal regulation (CFR) to ensure that the necessary competencies would be consistent from city to city while still permitting the cities the flexibility to determine those levels in which they needed more training (10).

It was decided that, where possible, existing courses within the Department of Defense and other federal agencies, like the Chemical Stockpile Emergency Preparedness program, would be modified to provide the basis of the initial programs of instruction. By using civilian medical personnel to rescript these courses, the military teaching materials would be tailored to meet the needs of the first response community. The train-the trainer approach was adopted to increase the size of the audience reached and to foster the development of networks of instructors at the local level to provide ongoing education for their personnel using existing internal education structures. Leave-behind materials that could be reproduced included copies of the instructor and student manuals, video presentations, 35 mm PowerPoint slides, CD-ROMs, and training aids. A toll-free NBC Domestic Preparedness Helpline and a web site were provided to allow for technical assistance and as a resource to research additional questions that were raised during the course of training (11).

Prior to the program being taken to each city, the local governments were provided with a self-assessment tool to help determine the training requirements and needs of each municipality. Initially learning was primarily didactic in structure with few “show-and-tell” and “hands-on” sessions, although these did increase as the program evolved. The Technician–Emergency Medical Services (EMS) course was unique in that it concluded with a triage exercise with

moulaged victims; most students found it to be the highlight of the training session.

moulaged victims; most students found it to be the highlight of the training session.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree