Evolution of the Disease and Its Management

Introduction

|

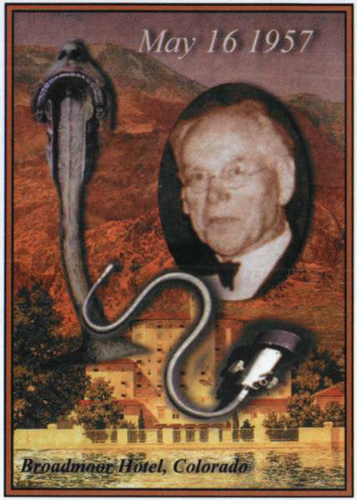

The apparent late recognition of esophagitis as a widespread disease has given cause for much discussion. Surprise has been expressed at the relative lack of reference to it before the mid-nineteenth century, and even thereafter it was noted to be quite rare. Numerous factors reflect the apparent obscurity of the disease until recently. These include the lack of a clear understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the organ, confusion regarding differentiation between its symptomatology and that of the stomach, and, lastly, the lack of opportunity and technology to adequately study it. Of particular importance in terms of the latter aspect of the problem was the advent at the beginning of the twentieth century of rigid endoscopy and the introduction of first bismuth and then barium upper gastrointestinal radiologic studies. The subsequent evolution of fiberoptic endoscopy in the 1960s provided major access to the esophageal lumen, as did the introduction of manometry and pH probe devices to the elucidation of the function of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The delineation of the secretion of acid and the ability to document its relationship to acid peptic disease, as well as the recognition of the concept of reflux as a related but separate disease process, facilitated the ability of physicians to focus on the esophagogastric junction as an area of considerable medical relevance.

The prolonged anatomic course of the esophagus caused confusion in the attribution of symptoms. Thus, upper area complaints were often considered to be of oral or throat origin and pathology in the mediastinal course erroneously attributed to the heart. Similarly, at the lower end, the symptoms, as well as their relationship to ingested food, often led to the conclusion that the problem was of gastric origin. Furthermore, the path of the esophagus deep within the posterior mediastinum rendered its study difficult, and speculation rather

than evaluation confounded a clear elucidation of its pathology and delayed the evolution of its rational therapy. Indeed, well into the twentieth century, the upper third was regarded as the province of the otolaryngologist, whereas the lower component was considered a part of the stomach. Few physicians laid claim to the middle third, because most cardiothoracic surgeons directed their attention to the more dynamic structures of the heart and lungs. Indeed, as early as 1946, John Tilden Howard, the secretary of the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, had been vocal in pointing out to gastroenterologists the need to examine the esophagus. By the 1950s, the advent of therapeutic strategies for esophageal disease rendered it apparent that the esophagus was no longer terra incognita, or no man’s land.

than evaluation confounded a clear elucidation of its pathology and delayed the evolution of its rational therapy. Indeed, well into the twentieth century, the upper third was regarded as the province of the otolaryngologist, whereas the lower component was considered a part of the stomach. Few physicians laid claim to the middle third, because most cardiothoracic surgeons directed their attention to the more dynamic structures of the heart and lungs. Indeed, as early as 1946, John Tilden Howard, the secretary of the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, had been vocal in pointing out to gastroenterologists the need to examine the esophagus. By the 1950s, the advent of therapeutic strategies for esophageal disease rendered it apparent that the esophagus was no longer terra incognita, or no man’s land.

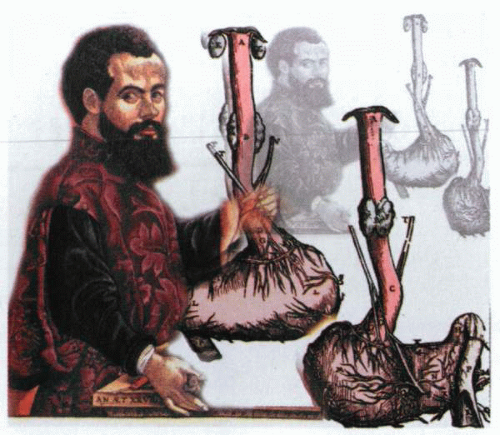

Ye meri or ysopaghus

Although seemingly a straightforward topic, the consideration of the esophagus and its disease has proved to be a subject of considerable vexation to physicians. The esophagus has long languished as an organ not highly regarded by any group and little understood by either laypersons or physicians. Some wits even referred to it as the humble organ, because so little attention had been devoted to it. To some extent, this reflected its course through three different anatomical territories—the neck, mediastinum, and abdomen—and the reluctance of the medical specialists of each group to claim the organ as their own. Even its name is poorly understood, and much conjecture exists regarding the origin of the term. Although the name is considered to have originally derived from an old Homeric term for the gullet, the meaning became transmuted to reflect a combination of swallowing and food, thus becoming interpreted as “a tube that conveys food.” Aristotle claimed that the name derived from its narrowness and length, and some etymologists have even linked the origin of the word to an osier twig, because the old Greek term could also be translated as an “eater of osiers.” Whether this reflected the early usage of such flexible branches in the treatment of esophageal obstructions is not recorded. Although the earliest English use of the term is recorded in 1398 in a manuscript in the Bodleian collection that refers to “Ysophagus, that is the wey of

mete and drinke,” by 1541, Guydon stated, “the Meri otherwise called Ysophagus is ye way of the mete & this Meri commeth out of the throte and thyrleth the mydryfe unto ye bely or stomacke.”

mete and drinke,” by 1541, Guydon stated, “the Meri otherwise called Ysophagus is ye way of the mete & this Meri commeth out of the throte and thyrleth the mydryfe unto ye bely or stomacke.”

The etymology of symptomatology

The history of the subject of esophagitis is mired in the confusion regarding the terminology used to describe its symptomatology, as well as by a failure to appreciate the organ as a separate entity from the stomach or the mouth. Thus dyspepsy, or, as it is more latterly referred to, dyspepsia, was in 1656 referred to by Blount as dyspesie and in 1661 by Lovell as an “imbecility of the stomach, which is a vice of the concocting faculty and is called apepsy, bradyspepsy, or dispepsy and diaphthora.” The recognition that it might be caused by both acid and bile appears to reside in the 1829 notation of Southey, who in Epistle in Anniversary noted the sensations evoked “by bile, opinions, and dyspepsy sour!” The relationship between the mind, stress, and acid disorders may have been first noted by Lowell, who in the 1848 Fable for Critics opined that an individual had been “brought to death’s door of a mental dyspepsy.” Similarly, the subject of heartburn, which was initially regarded as a heated and embittered state of mind that is felt but not openly expressed, was described by Shakespeare in Richard III as “A long continued grudge and hearte brennynge betwene the Quenes kinred and the kinges blood.” An awareness of this problem dates back to 1591, when Percivall described “a sharpnes, sowernes of stomack, hartburning.” Thereafter, Swan, in 1635, expressed the opinion that “Lettice cooleth a hot stomach called heart-burning.” As early as 1607, Topsell noted the potential severity of the disease, commenting on the “the hearts of them that die of the heart-burning disease.” Of note was the fact that in 1747, Wesley identified that heart burning was “a sharp gnawing pain at the orifice of the Stomach.”

Nevertheless, the esophagus claimed early medical attention, given the propensity of foreign bodies to obstruct it and the rapid onset of symptoms once ingress of fluids or liquids into the stomach was impaired. Furthermore, there was the disturbing sensation in the chest that caused intense discomfort and was associated with the eating of certain kinds of food. Given the location of the pain and the concept of cardiac dominance in medicine, it was assumed that the origin of the discomfort was the heart and not the esophagus; hence, cardalgia and cardialgy were terms first used to describe the uneasy burning sensation in the lower part of the chest. The cause was believed to be indicative of putrefactive fermentation in the stomach. This confusion was further amplified by anatomic nomenclature that referred to the upper portion of the stomach as the cardia. An additional term, cardiodynia, was also used in the nosology of Cullen and was a part of a complex classification that sought to characterize a wide variety of “pain,” thereby further defining the origin of a particular disease. Since the time of Harvey and the description of the circulation of the blood, the ebb and flow of bodily fluids through valves and orifices had been acceptably described as examples of flux and reflux. It was therefore well accepted that food might reflux out of the gastric storage vat, and the descriptive term used to describe the consequences of reflux thus alluded not only to the burning sensation, heartburn, but its sequela, namely, cardiospasm. As early as 1597, Gerard, in his Herbal, noted that “a small stonecrop is good for hart-burne,” whereas Buchan, in 1790, could state with assurance, “I have frequently known the heart-burn to be cured by chewing green tea.” A more contemporary comment by Beale, in 1880, stated, “chalk or magnesia is taken for the relief of heartburn.”

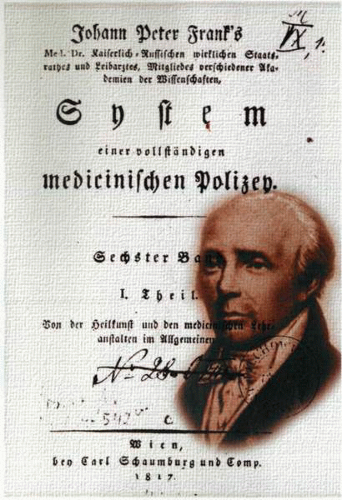

Esophagitis

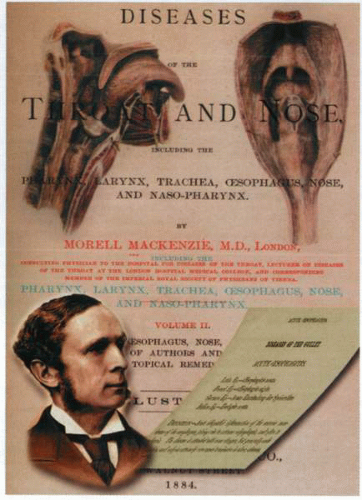

The first description of the disease by Galen was accurate, although somewhat incomplete. Nevertheless, he duly noted that, although difficulties with swallowing may be due to tumors or paralysis, the esophagus, when inflamed, interfered with swallowing by itself acting as a hindrance due to the associated excruciating pain. In 1884, Morell Mackenzie defined esophagitis as an “acute idiopathic inflammation of the mucous membranes of the esophagus giving rise to extreme odynophagia and often to aphagia.” It was this Anglicized description that was used to qualify the disease known as esophagitis, which had first properly been described by John Peter Frank in 1792.

Although similar observations had been made previously in 1722 by Boehm, who described an acute pain “which reached down even to the stomach and which was accompanied by hiccup and a constant flow of serum from the mouth,” he had not defined the condition as accurately. Honkoop published a thesis on inflammation of the gullet in 1774, and in 1785, Bleuland, a physician himself, was struck down with the disease and carefully recorded the details of his

illness. The first reports of the condition of esophagitis in children originated with Billard, who, in 1828, published a statement regarding the ailments of newborns. In 1829, Mondière wrote a thesis describing his own severe personal experiences with esophagitis and in addition collected much of the extant material on the subject. His laborious compilation represents more industry than discrimination, but the thesis provides a good overview of early nineteenth-century thoughts on the esophagus. Indeed, it is from the work of Mondière that much of the literature sources of esophageal diseases were drawn for the next century. These included Velpeau’s The Esophagus—A Dictionary in Four Volumes, Follin’s essay “Considerations of Esophageal Disease,” and Copland’s Dictionary. In 1835, Graves of Dublin made some observations on the disease but, thereafter, confined his attentions to the thyroid, achieving eponymous recognition for his contributions to the subject. In 1878, Knott, in Dublin, published The Pathology of the Esophagus and included in it the cases of esophagitis described by Roche, Bourguet, Broussais, and Paletta, as well as some original illustrations of diseases of the organ. The topic of the esophagus was further illuminated by communications from Hamburger, Padova, Laboulbène, and a number of other distinguished physicians of the time, but little novel was added to the understanding of the subject.

illness. The first reports of the condition of esophagitis in children originated with Billard, who, in 1828, published a statement regarding the ailments of newborns. In 1829, Mondière wrote a thesis describing his own severe personal experiences with esophagitis and in addition collected much of the extant material on the subject. His laborious compilation represents more industry than discrimination, but the thesis provides a good overview of early nineteenth-century thoughts on the esophagus. Indeed, it is from the work of Mondière that much of the literature sources of esophageal diseases were drawn for the next century. These included Velpeau’s The Esophagus—A Dictionary in Four Volumes, Follin’s essay “Considerations of Esophageal Disease,” and Copland’s Dictionary. In 1835, Graves of Dublin made some observations on the disease but, thereafter, confined his attentions to the thyroid, achieving eponymous recognition for his contributions to the subject. In 1878, Knott, in Dublin, published The Pathology of the Esophagus and included in it the cases of esophagitis described by Roche, Bourguet, Broussais, and Paletta, as well as some original illustrations of diseases of the organ. The topic of the esophagus was further illuminated by communications from Hamburger, Padova, Laboulbène, and a number of other distinguished physicians of the time, but little novel was added to the understanding of the subject.

Although Mackenzie regarded the condition to be of unknown etiology (1884), he carefully defined the chief symptom as excruciating burning or tearing pain—odynophagia—induced by any attempt to swallow or any movement of the laryngeal muscles. He also noted that such patients developed considerable thirst but were unable to achieve relief by drinking, because the pain was so severe. In adults, he reported that there was a constant expectoration of frothy saliva, and although patients might not always have a fever, they often became delirious. Mackenzie believed the lesion to represent a diffuse catarrhal inflammation of the mucosa of the upper end of the gullet and felt the diagnosis was based on the history of extreme pain and the absence of pharyngeal inflammation on examination!

Although the description by Mackenzie of esophagitis is very different from that now recognized to represent the contemporary understanding of the disease, his is the first lucid attempt to define the subject. His text Diseases of the Throat and Nose contains a fascinating and detailed analysis, as well as classification of esophagitis, but sometimes fails to accurately distinguish between disease of the lower and upper end of the gullet. In the twentieth century, the term esophagitis has become referable almost solely to an entity involving the lower part of the gullet. Nevertheless, Mackenzie recognized that the inflammatory conditions of the upper part of the gullet were

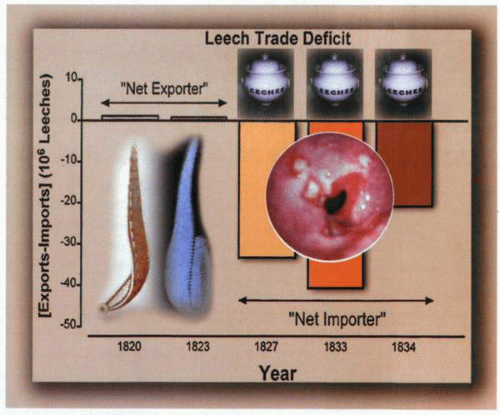

specific and included diphtheria, thrush, tuberculosis, syphilis, actinomycosis, and corrosive damage. Some of the associated nonspecific conditions (myalgia, general hyperesthesia) alluded to by Mackenzie are no longer recognized, but as late as 1900, all inflammatory conditions affecting the gullet were still regarded as varieties of esophagitis. Of particular interest were the treatments proposed in the management of this vexatious condition. It was considered mandatory that the organ be maintained in a state of absolute rest. Thus, feeding was undertaken by nutrient enemata and morphia administered by hypodermic injection to facilitate resolution of inflammation and abolish pain. Poultices were applied along the upper part of the spine, or, if the pain was particularly severe, anodyne embrocations, such as oleate of morphia or belladonna lineaments, were rubbed into the back. Mondière, following the French practice of the time, believed in venesection and cupping as well as leech applications (12 to 30 at a time).

specific and included diphtheria, thrush, tuberculosis, syphilis, actinomycosis, and corrosive damage. Some of the associated nonspecific conditions (myalgia, general hyperesthesia) alluded to by Mackenzie are no longer recognized, but as late as 1900, all inflammatory conditions affecting the gullet were still regarded as varieties of esophagitis. Of particular interest were the treatments proposed in the management of this vexatious condition. It was considered mandatory that the organ be maintained in a state of absolute rest. Thus, feeding was undertaken by nutrient enemata and morphia administered by hypodermic injection to facilitate resolution of inflammation and abolish pain. Poultices were applied along the upper part of the spine, or, if the pain was particularly severe, anodyne embrocations, such as oleate of morphia or belladonna lineaments, were rubbed into the back. Mondière, following the French practice of the time, believed in venesection and cupping as well as leech applications (12 to 30 at a time).

Counterirritation by the application of mustard poultices or moxas was also widely recommended. By 1884, however, Mackenzie was able to declare that bleeding or even the local abstraction of blood was of little value, and that he himself had found counterirritation to be of no effect. He favored derivatives and especially recommended the use of extremely hot

pediluvia. Bleuland used blisters loco dolenti between the shoulders with success, and Pagenstecher reported the use of hydrochloride of ammonia to great advantage. This agent had long been a favorite of German and Dutch physicians and was used as a remedy for many different kinds of diseases. Mackenzie was adamant that the passage of bougies was dangerous and should never be attempted, because it was likely to cause rupture of the esophagus. Once convalescence commenced, the patient could be changed from a liquid to a solid diet gradually, and if pain returned, immediate return to a liquid diet should once again be undertaken.

pediluvia. Bleuland used blisters loco dolenti between the shoulders with success, and Pagenstecher reported the use of hydrochloride of ammonia to great advantage. This agent had long been a favorite of German and Dutch physicians and was used as a remedy for many different kinds of diseases. Mackenzie was adamant that the passage of bougies was dangerous and should never be attempted, because it was likely to cause rupture of the esophagus. Once convalescence commenced, the patient could be changed from a liquid to a solid diet gradually, and if pain returned, immediate return to a liquid diet should once again be undertaken.

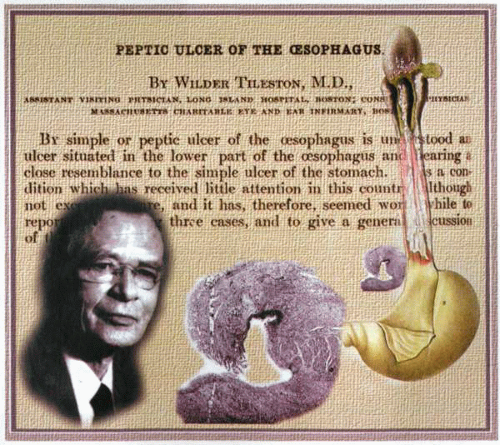

Despite the attention to the gullet provided by Mackenzie, esophagitis per se was not commonly recognized, and little was known about it. In 1906, Wilder Tileston carefully defined at least 12 different types of ulceration, which included carcinoma, corrosive, foreign bodies, acute infectious diseases, decubitus, aneurysms, catarrhal inflammations, those associated with diverticulum, tuberculosis, syphilis, varicose, and ulcers due to thrush. Tileston was particularly drawn to the disease that he referred to as peptic ulcer of the esophagus, which he claimed exactly simulated the behavior and appearance of chronic gastric ulcer. He noted that, although a rare entity, it had initially been described by Albers in 1839 and thereafter sporadically noted by pathologists. No less an authority than C. Rokitansky (1804-1878) had concurred that peptic ulcer of the lower esophagus was a real and definable entity and represented the aftermath of gastric juice in the gullet. Nevertheless, when Tileston reviewed the literature, as far as 1906, there had only been 44 clear-cut examples of the condition published. The ulcers described were usually single and often associated with chronic peptic ulcer in the stomach or the duodenum. They were large, penetrating lesions sometimes 6

to 8 cm in length that lay “above the cardiac sphincter” and, although often longitudinal, might also encircle the entire gullet.

to 8 cm in length that lay “above the cardiac sphincter” and, although often longitudinal, might also encircle the entire gullet.

The patients were elderly, and many had no symptoms referable to the esophagus until their admission to the hospital. Death usually occurred from perforation into a large vessel, the pericardium, the mediastinum, or the pleural cavity, although some died of pneumonia. Of interest was the fact that few exhibited symptoms of esophageal obstruction. Tileston further reported that the histology of such ulcers was identical to that of chronic gastric ulcer, and that the adjacent mucosa was gastric in type. He assumed it to be “ectopic,” because it lined the lower part of the gut in the mediastinum.

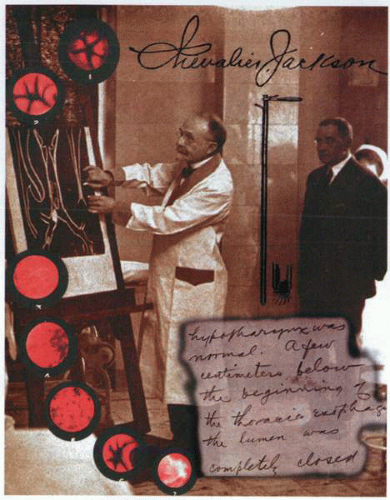

The understanding of ulceration of the esophagus and esophagitis itself became further obfuscated with the advent of radiology and esophagoscopy at the turn of the nineteenth century. The use of these diagnostic tools enabled the identification of a variety of esophageal lesions, particularly ulcers and inflammation at the lower end of the gullet not previously apparent to clinicians. Thus, by the 1920s, it was apparent that pathologists, clinicians, and endoscopists, although assuming that they were describing the same entity when they referred to peptic ulcer of the esophagus or esophagitis, were each unclear as to the exact nature of the disease process. In 1929, Chevalier Jackson, a virtuoso esophagoscopist, reported 88 cases in 4,000 consecutive endoscopies, whereas Stewart and Hartfall in the same year claimed that they were able to identify only one example of esophagitis in 10,000 consecutive autopsies.

The subsequent reports of Lyall (1937), Chamberlin (1939), and Dick and Hurst (1942) provided further insight into the nature and occurrence of these lower esophageal lesions. The further substantial contributions by Paul Allison and Johnstone of Leeds (1943, 1946, and 1948) left little doubt that the authors were confident in their ability to recognize and diagnose “peptic ulcer of the esophagus” or “esophagitis.”

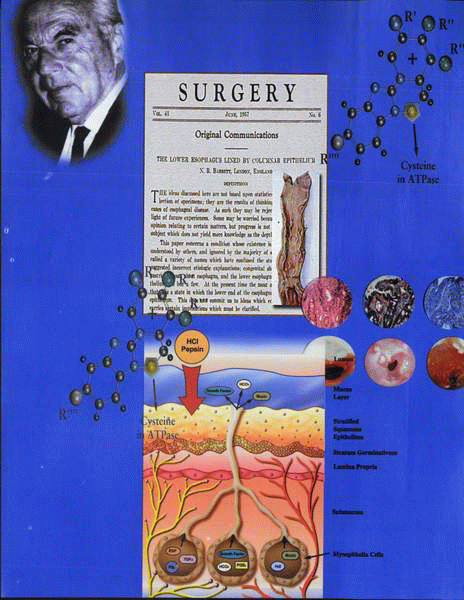

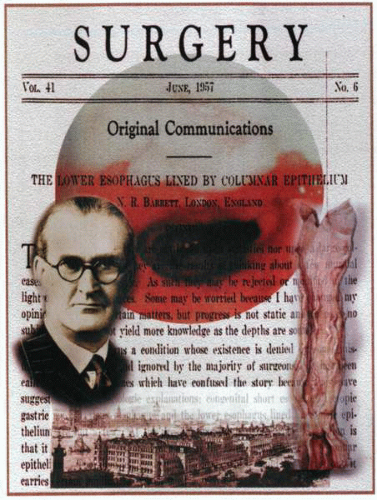

The Beatitude of Barrett

Norman Barrett believed that the early descriptions of ulcer by Tileston, Stewart, and Lyall differed significantly from those identified by clinicians such as Allison. He felt that the former were rare and of little clinical significance, whereas the latter were common and important entities. He further proposed that this confusion had arisen because the pathology of the former had been tacked on to the symptomatology of the latter. Indeed, it was Barrett’s opinion that the condition described in 1948 by Allison actually represented reflux esophagitis, and that this was the best name for the lesion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree