Evidence Transfer

|

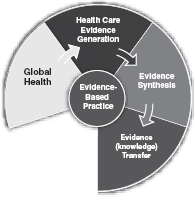

Broadly speaking, evidence transfer refers to the practical issue of transferring pre-reviewed, appraised, robust evidence to the policy and practice areas. It involves capturing, organizing and distributing evidence in ways that ensure it is available, accessed and ultimately used in policy and practice. Evidence transfer is complex because health bureaucracies, health systems and health professionals are diverse in the ways they access and use knowledge and systems, policies and practices are often grounded in well established, tacit and traditional views that are often strongly held on to. Transferring evidence into policy and practice is demonstrated when changes in policy and practice correlate with the best available evidence.

Critical factors involved in transferring evidence into policy and practice

Great strides have been made in recent times in approaches to the transfer of evidence. The degree to which evidence-based information related to best practice in healthcare is accessed and adopted depends upon the nature of the evidence; its perceived strength or reliability (often linked to where it comes from); the ways in which it is delivered; the way in which it is presented in relation to who it is designed for; and the organizational context within which the transfer occurs.

The perceived strength or reliability of the evidence to be transferred

The evidence suggests that both policymakers and health professionals are more likely to access and apply evidence-based information if it is clear, brief and provides answers to clinically or policy relevant questions. Turner (2009), in a study of health professionals in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Australia, reports that clinicians want “… key clinical recommendations…based on the best available research evidence…”

Many health services, health systems and commercial publishers seek to produce information to inform policy and practice based on literature reviews and consensus. Such locally and commercially produced information is often not based on rigorous systematic reviews of the literature by independent reviewers with expertise in evidence reviews and health professionals may regard it as “… not evidence-based necessarily, but just current practice and what works and maybe what other hospitals do locally, but nothing really technically evidence-based.” (Turner, 2009, p. 3)

The “strength” or validity of the evidence is an important factor in the successful transfer process. The utility of information generated from conducting systematic reviews relies quite substantially on the existence of a system for grading the evidence. This process is an important element when making recommendations for practice in order to enable health professionals to distinguish recommendations based on consensus from those based on good quality studies with consistent findings (Hutchinson & Baker, 1999). They suggest that grading of evidence statements in guidelines should be readily understandable as their function is to alert the busy decision maker to the strength or weakness of specific statements. Atkins, Eccles, Flottorp, Guyatt, Henry, Hill, Liberati, O’Connell et al (2004) describe the “GRADE” approach to assessing the strength of recommendations in evidence summaries or statements. GRADE Judgments about evidence and recommendations in healthcare are complex. For example, those making recommendations between recommending selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI’s) or tricyclics for the treatment of moderate depression must agree on which outcomes to consider, which evidence to include for each outcome, how to assess the quality of that evidence, and how to determine if SSRI’s do more good than harm compared with tricyclics. Because resources are always limited and money that is allocated to treating depression cannot be spent on other worthwhile interventions, they may also need to decide whether any incremental health benefits are worth the additional costs.

Systematic reviews of the effects of healthcare provide essential, but not sufficient information for making well informed decisions. Reviewers and people who use reviews draw conclusions about the quality of the evidence, either implicitly or explicitly. Such judgments guide subsequent decisions. For example,

The GRADE system offers two grades of recommendations: “strong” and “weak” (though guideline panels may prefer terms such as “conditional” or “discretionary” instead of weak). When the desirable effects of an intervention clearly outweigh the undesirable effects, or clearly do not, guideline panels offer strong recommendations. On the other hand, when the tradeoffs are less certain—either because of low quality evidence or because evidence suggests that desirable and undesirable effects are closely balanced—weak recommendations become mandatory.

Many organizations utilize a three-point scale, as in Table 1; however, such scales are not always reflective of the breadth of research evidence.

These grades of recommendations – designed to inform clinicians, policymakers and decision makers – draw on the quality of the evidence itself. It is now well accepted in health that there is a hierarchy of evidence in terms of the relative authority of various types of evidence. Although there is no single, universally-accepted hierarchy of evidence, the dominant view is that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) rank above observational studies; and that

expert opinion and anecdotal experience rank at the lower end of the hierarchy. Most evidence hierarchies place the systematic review that includes meta analysis above RCTs. In order to accommodate such differences in evidence, a number of complex scales have been developed, including one developed by the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford, UK (Table 2).

expert opinion and anecdotal experience rank at the lower end of the hierarchy. Most evidence hierarchies place the systematic review that includes meta analysis above RCTs. In order to accommodate such differences in evidence, a number of complex scales have been developed, including one developed by the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford, UK (Table 2).

Table 1. Three Point Level of Evidence Scale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

There is considerable variation in approaches to evidence tables in terms of levels and when they should be used. The international debate about evidence tables is vigorous and although there is no consensus the trend is toward revisiting the use of grades of recommendation. As an international collaboration, with an interest in expanding the definition of evidence to include evidence of Feasibility, Appropriateness, Meaningfulness and Economic Impact, the Joanna Briggs Institute adopted the evidence hierarchy in Table 3 in 2004.

Systematic reviewers with expertise in research methods use Levels of Evidence to determine the quality of evidence. Grades of Recommendation are often used in abstracted evidence, evidence summaries or clinical guidelines.

The way in which evidence is delivered

Robust evidence assembled through a rigorous process of review can be delivered or disseminated through written or oral means that are either formal or informal and includes education and training, online delivery systems and printed resources. Central to designing ways to transfer knowledge or evidence to the point of decision-making is determining:

The level of detail desired by, and appropriate to, the specific user group (e.g. policymakers; clinical nurses or physicians; medical or nursing administrators); and

The amount of information that can be reasonably assimilated when the user accesses the evidence source.

Jacobson, Butterill and Goering (2003) suggest that an awareness of the user group is a fundamental requirement in the effective transfer of knowledge. Most health professions are increasingly embracing the use of evidence-based resources to inform (rather than direct) practice and this is a response to high profile promotional initiatives of governments and

provider agencies in individual countries. For example, in the U.S., considerable resources have been invested to provide summaries of evidence and the National Institutes of Health now have a well-established strategy to review international literature and conduct meta analyzes to generate guidance based on the best available evidence. Practical application of rigorously reviewed evidence is now promoted through the development and dissemination of appraised and summarized evidence in most developed healthcare systems.

provider agencies in individual countries. For example, in the U.S., considerable resources have been invested to provide summaries of evidence and the National Institutes of Health now have a well-established strategy to review international literature and conduct meta analyzes to generate guidance based on the best available evidence. Practical application of rigorously reviewed evidence is now promoted through the development and dissemination of appraised and summarized evidence in most developed healthcare systems.

Table 2. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence (March 2009) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree