KEY POINTS

The physician should document that the patient or surrogate has the capacity to make a medical decision.

The physician discloses to the patient details regarding the diagnosis and treatment options sufficient for the patient to make an informed consent.

Living wills are written to anticipate treatment options and choices in the event that a patient is rendered incompetent by a terminal illness.

The durable power of attorney for healthcare identifies surrogate decision makers and invests them with the authority to make healthcare decisions on the patient’s behalf in the event that they are unable to speak for themselves.

Surgeons should encourage their patients to clearly identify their surrogates early in the course of treatment.

Earlier referral and wider use of palliative and hospice care may help more patients achieve their goals at the end of life.

Seven requirements for the ethical conduct of clinical trials have been articulated: value, scientific validity, fair subject selection, favorable risk-benefit ratio, independent review, informed consent, and respect for enrolled subjects.

Disclosure of error is consistent with recent ethical advances in medicine toward more openness with patients and the involvement of patients in their care.

Dedicated to the advancement of surgery along its scientific and moral side.

June 10, 1926, dedication on the Murphy Auditorium, the first home of the American College of Surgeons

WHY ETHICS MATTER

Ethical concerns involve not only the interests of patients, but also the interests of surgeons and society. Surgeons choose among the options available to them because they have particular opinions regarding what would be good (or bad) for their patients. Aristotle described practical wisdom (Greek: phronesis) as the capacity to choose the best option from among several imperfect alternatives (Fig. 48-1).1 Frequently, surgeons are confronted with clinical or interpersonal situations in which there is incomplete information, uncertain outcomes, and/or complex personal and familial relationships. The capacity to choose wisely in such circumstances is the challenge of surgical practice.

Figure 48-1.

Bust of Aristotle. Marble, Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Lysippos from 330 b.c. [From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aristotle_Altemps_Inv8575.jpg: Ludovisi Collection, Accession number Inv. 8575, Palazzo Altemps, Location Ground Floor, Branch of the National Roman Museum. Photographer/source Jastrow (2006) from Wikipedia (accessed April 8, 2014).]

DEFINITIONS AND OVERVIEW

Biomedical ethics is the system of analysis and deliberation dedicated to guiding surgeons toward the “good” in the practice of surgery. One of the most influential ethical “systems” in the field of biomedical ethics is the principalist approach as articulated by Beauchamp and Childress.2 In this approach to ethical issues, moral dilemmas are deliberated by using four guiding principles: autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice.2

The principle of autonomy respects the capacity of individuals to choose their own destiny, and it implies a right for individuals to make those choices. It also implies an obligation for physicians to permit patients to make autonomous choices about their medical care. Beneficence requires that proposed actions aim at and achieve something good whereas nonmaleficence aims at avoiding concrete harm: primum non nocere. Justice requires fairness where both the benefits and burdens of a particular action are distributed equitably.

The history of medical ethics has its origins in antiquity. The Hippocratic Oath along with other professional codes has guided the actions of physicians for thousands of years. However, the growing technical powers of modern medicine raise new questions that were inconceivable in previous generations. Life support, dialysis, and modern drugs, as well as organ and cellular transplantation, have engendered new moral and ethical questions. As such, the ethical challenges faced by the surgeon have become more complex and require greater attention.

The case-based paradigm for bioethics is used when the clinical team encounters a situation in which two or more values or principles come into apparent conflict. The first step is to clarify the relevant principles (e.g., autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice) and values at stake (e.g., self-determination, quality of life, etc.). After identifying the principles and values that are affecting the situation, a proposed course of action is considered given the circumstances.

Much of the discourse in bioethics adopts this “principlist” approach in which the relevant principles are identified, weighed and balanced, and then applied to formulate a course of action. This approach to bioethics is a powerful technique for thinking through moral problems because the four principles help identify what is at stake in any proposed course of action. However, the principles themselves do not resolve ethical dilemmas. Working together, patients and surgeons must use wise judgment to choose the best course of action for the specific case.

Choosing wisely requires the virtue of practical wisdom first described by Aristotle (Fig. 48-1). Along with the other cardinal virtues of courage, justice and temperance, practical wisdom is a central component of virtue ethics which complement principlist ethics by guiding choices toward the best options for treatment. Practical wisdom cannot be learned from books and is developed only through experience. The apprenticeship model of surgical residency fosters the development of practical wisdom through experience. More than teaching merely technical mastery, surgical residency is also moral training. In fact, the sociologist Charles Bosk argues that the “postgraduate training of surgeons is above all things an ethical training.”3

“First do no harm.”

SPECIFIC ISSUES IN SURGICAL ETHICS

Although a relatively recent development, the doctrine of informed consent is one of the most widely established tenets of modern biomedical ethics. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most physicians practiced a form of benign paternalism whereby patients were rarely involved in the decision-making process regarding their medical care, relying instead on the beneficence of the physician. Consensus among the wider public eventually changed such that surgeons are now expected to have an open discussion about diagnosis and treatment with the patient to obtain informed consent. In the United States, the legal doctrine of simple consent dates from the 1914 decision in Schloendorff vs. The Society of New York Hospital regarding a case in which a surgeon removed a diseased uterus after the patient had consented to an examination under anesthesia, but with the express stipulation that no operative excision should be performed. The physician argued that his decision was justified by the beneficent obligation to avoid the risks of a second anesthetic. However, Justice Benjamin Cardozo stated:

Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his body; and a surgeon who performs an operation without his patient’s consent commits an assault, for which he is liable in damages … except in cases of emergency, where the patient is unconscious, and where it is necessary to operate before consent can be obtained.4

Having established that patients have the right to determine what happens to their bodies, it took some time for the modern concept of informed consent to emerge from the initial doctrine of simple consent. The initial approach appealed to a professional practice standard whereby physicians were obligated to disclose to patients the kind of information that experienced surgeons customarily disclosed.5 However, this disclosure was not always adequate for patient needs. In the 1972 landmark case, Canterbury vs. Spence, the court rejected the professional practice standard in favor of the reasonable person standard whereby physicians are obliged to disclose to patients all information regarding diagnosis, treatment options, and risks that a “reasonable patient” would want to know in a similar situation. Rather than relying on the practices or consensus of the medical community, the reasonable person standard empowers the public (reasonable persons) to determine how much information should be disclosed by physicians to ensure that consent is truly informed. The court did recognize, however, that there are practical limits on the amount of information that can be communicated or assimilated.5 Subsequent litigation has revolved around what reasonable people expect to be disclosed in the consent process to include the nature and frequency of potential complications, the prognostic life expectancy,6 and the surgeon-specific success rates.4 Despite the litigious environment of medical practice, it is difficult to prosecute a case of inadequate informed consent so long as the clinician has made a concerted and documented effort to involve the patient in the decision-making process.

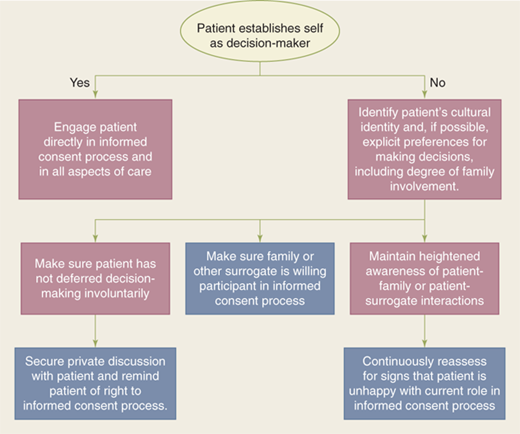

Adequate informed consent entails at least four basic elements: (a) the physician documents that the patient or surrogate has the capacity to make a medical decision; (b) the surgeon discloses to the patient details regarding the diagnosis and treatment options sufficiently for the patient to make an informed choice; (c) the patient demonstrates understanding of the disclosed information before (d) authorizing freely a specific treatment plan without undue influence (Fig. 48-2). These goals are aimed at respecting each patient’s prerogative for autonomous self-determination. To accomplish these goals, the surgeon needs to engage in a discussion about the causes and nature of the patient’s disease, the risks and benefits of available treatment options, as well as details regarding what patients can expect after an operative intervention.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14

Informed consent can be challenging in certain clinical settings. For example, obtaining consent for emergency surgery, where decisions are often made with incomplete information, can be difficult. Emergency consent requires the surgeon to consider if and how possible interventions might save a patient’s life, and if successful, what kind of disability might be anticipated. Surgical emergencies are one of the few instances where the limits of patient autonomy are freely acknowledged, and surgeons are empowered by law and ethics to act promptly in the best interests of their patients according to the surgeon’s judgment. Most applicable medical laws require physicians to provide the standard of care to incapacitated patients, even if it entails invasive procedures without the explicit consent of the patient or surrogate. If at all possible, surgeons should seek the permission of their patients to provide treatment, but when emergency medical conditions render patients unable to grant that permission, and when delay is likely to have grave consequences, surgeons are legally and ethically justified in providing whatever surgical treatment the surgeon judges necessary to preserve life and restore health.4 This justification is based on the social consensus that most people would want their lives and health protected in this way, and this consensus is manifest in the medical profession’s general orientation to preserve life. It may be that subsequent care may be withdrawn or withheld when the clinical prognosis is clearer, but in the context of initial resuscitation of injured patients, incomplete information makes clear judgments about the patient’s ultimate prognosis or outcome impossible.

The process of consent can also be challenging in the pediatric population. For many reasons, children and adolescents cannot participate in the process of giving informed consent in the same way as adults. Depending on their age, children may lack the cognitive and emotional maturity to participate fully in the process. In addition, depending on the child’s age, their specific circumstances, as well as the local jurisdiction, children may not have legal standing to fully participate on their own independent of their parents. The use of parents or guardians as surrogate decision makers only partially addresses the ethical responsibility of the surgeon to involve the child in the informed consent process. The surgeon should strive to augment the role of the decision makers by involving the child in the process. Specifically, children should receive age-appropriate information about their clinical situation and therapeutic options so that the surgeon can solicit the child’s “assent” for treatment. In this manner, while the parents or surrogate decision makers formally give the informed consent, the child remains an integral part of the process.

Certain religious practices can present difficulties in treating minor children in need of life-saving blood transfusions; however, case law has made clear the precedent that parents, regardless of their held beliefs, may not place their minor children at mortal risk. In such a circumstance, the physician should seek counsel from the hospital medicolegal team, as well as from the institutional ethics team. Legal precedent has, in general, established that the hospital or physician can proceed with providing all necessary care for the child.

Obtaining “consent” for organ donation deserves specific mention.15 Historically, discussion of organ donation with families of potential donors was performed by transplant professionals, who were introduced to families by intensivists after brain death had been confirmed and the family had been informed of the fact of death. In other instances, consent might be obtained by intensivists caring for the donor, as they were assumed to know the patient’s family and could facilitate the process. However, issues of moral “neutrality” as part of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit have caused a shift in how obtaining “consent” for organ donation is handled. Responsibility for obtaining consent from the donor family is now vested in trained “designated requestors” (or “organ procurement coordinators”)16 or by “independent” intensivists who do not have a therapeutic clinical relationship with the potential donor.17 In this way, the donor family can be allowed to make the decision regarding donation in a “neutral” environment without erosion of the therapeutic relationship with the treating physician.

The process of informed consent also can be limited by the capacity of patients to assimilate information in the context of their illness. For example, despite the best efforts of surgeons, evidence suggests that patients rarely retain much of what is disclosed in the consent conversation, and they may not remember discussing details of the procedure that become relevant when postoperative complications arise.18 It is important to recognize that the doctrine of informed consent places the most emphasis on the principle of autonomy precisely in those clinical situations when, because of their severe illness or impending death, patients are often divested of their autonomy.

Severe illness and impending death can often render patients incapable of exercising their autonomy regarding medical decisions. One approach to these difficult situations is to make decisions in the “best interests” of patients, but because such decisions require value judgments about which thoughtful people frequently disagree, ethicists, lawyers. and legislators have sought a more reliable solution. Advanced directives of various forms have been developed to carry forward into the future the autonomous choices of competent adults regarding health care decisions. Furthermore, the courts often accept “informal” advanced directives in the form of sworn testimony about statements the patient made at some time previous to their illness. When a formal document expressing the patient’s advanced directives fails to exist, surgeons should consider the comments patients and families make when asked about their wishes in the setting of debilitating illness.

Living wills are written to anticipate treatment options and choices in the event that a patient is incapacitated by a terminal illness. In the living will, the patient indicates which treatments she wishes to permit or prohibit in the setting of terminal illness. The possible treatments addressed often include mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, artificial nutrition, dialysis, antibiotics, or transfusion of blood products. Unfortunately, living wills are often too vague to offer concrete guidance in complex clinical situations, and the language (“terminal illness,” “artificial nutrition”) can be interpreted in many ways. Furthermore, by limiting the directive only to “terminal” conditions, it does not provide guidance for common clinical scenarios like advanced dementia, delirium, or persistent vegetative states where the patient is unable to make decisions, but is not “terminally” ill. Perhaps even more problematic is the evidence that demonstrates that healthy patients cannot reliably predict their preferences when they are actually sick. This phenomenon is called “affective forecasting” and applies to many situations. For example, the general public estimates the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) score of patients on dialysis at 0.39, although dialysis patients themselves rate their HRQoL at 0.56.19 Similarly, patients with colostomies rated their HRQoL at 0.92, compared to a score of 0.80 given by the general public for patients with colostomies.19 For these and other reasons, living wills are often unable to provide the extent of assistance they promise.20

An alternative to living wills is the durable power of attorney for health care in which patients identify surrogate decision makers and invest them with the authority to make health care decisions on their behalf in the event that they are unable to speak for themselves. Proponents of this approach hope that the surrogate will be able to make decisions that reflect the choices that the patients themselves would make if they were able. Unfortunately, several studies demonstrate that surrogates are not much better than chance at predicting the choices patients make when the patient is able to state a preference. For example, a recent meta-analysis found that surrogates predicted patients’ treatment preferences with only 68% accuracy.21 These data reveal a flaw in the guiding principle of surrogate decision making: Surrogates do not necessarily have privileged insight into the autonomous preferences of patients. However, the durable power of attorney at least allows patients to choose the person who will eventually make prudential decisions on their behalf and in their best interests; therefore, respecting the judgment of the surrogate is a way of respecting the self-determination of the incapacitated patient.22

There is continuing enthusiasm for a wider use of advanced directives. In fact, the 1991 Patient Self Determination Act requires all U.S. health care facilities to (a) inform patients of their rights to have advanced directives, and (b) to document those advanced directives in the chart at the time any patient is admitted to the health care facility.4 However, only a minority of patients in U.S. hospitals have advanced directives despite concerted efforts to teach the public of their benefits. For example, the ambitious SUPPORT trial used specially trained nurses to promote communication between physicians, patients, and their surrogates to improve the care and decision making of critically ill patients. Despite this concerted effort, the intervention demonstrated “no significant change in the timing of do not resuscitate (DNR) orders, in physician-patient agreement about DNR orders, in the number of undesirable days (patients experiences), in the prevalence of pain, or in the resources consumed.”23

Some of the reluctance around physician-patient agreement about DNR orders may reflect patient and family anxiety that DNR orders equate to “do not treat.” Patients and families should be assured, when appropriate, that declarations of DNR/do not intubate will not necessarily result in a change in ongoing routine clinical care. The issue of temporarily rescinding DNR/do not intubate orders around the time of an operative procedure may also need to be addressed with the family.

Patients should be encouraged to clearly identify their surrogates, both formally and informally, early in the course of treatment, and before any major elective operation. Often, around the time of surgery or at the end of life, there are limits to patient autonomy in medical decision making. Seeking an advanced directive or surrogate decision maker requires time that is not always available when the clinical situation deteriorates. As such, these issues should be clarified as early as possible in the patient-physician relationship.

The implementation of various forms of life support technology raise a number of legal and ethical concerns about when it is permissible to withdraw or withhold available therapeutic technology. There is general consensus among ethicists that there are no philosophic differences between withdrawing (stopping) or withholding (not starting) treatments that are no longer beneficial.24 However, the right to refuse, withdraw, and withhold beneficial treatments was not established before the landmark case of Karen Ann Quinlan. In 1975, Quinlan lapsed into a persistent vegetative state requiring ventilator support. After several months without clinical improvement, Quinlan’s parents asked the hospital to withdraw ventilator support. The hospital refused, fearing prosecution for euthanasia. The case was appealed to the New Jersey Supreme Court where the justices ruled that it was permissible to withdraw ventilator support.25 This case established a now commonly recognized right to withdraw “extraordinary” life-saving technology if it is no longer desired by the patient or the patient’s surrogate.

The difference between “ordinary” and “extraordinary” care, and whether there is an ethical difference in withholding or withdrawing “ordinary” vs. “extraordinary” care, has been an area of much contention. The 1983 Nancy Cruzan case highlighted this issue. In this case, Cruzan had suffered severe injuries in an automobile crash that rendered her in a persistent vegetative state. Cruzan’s family asked that her tube feeds be withheld, but the hospital refused. The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that the tube feeding could be withheld if her parents demonstrated “clear and convincing evidence” that the incapacitated patient would have rejected the treatment.26 In this ruling, the court essentially ruled that there was no legal distinction between “ordinary” vs. “extraordinary” life-sustaining therapies.27 In allowing the feeding tube to be removed, the court accepted the principle that a competent person (even through a surrogate decision maker) has the right to decline treatment under the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The court noted, however, that there has to be clear and convincing evidence of the patient’s wishes (principle of autonomy) and that the burdens of the medical intervention should outweigh its benefits (consistent with the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence).

In deliberating the issue of withdrawing vs. withholding life-sustaining therapies, the principle of “double effect” is often mentioned. According to the principle of “double effect,” a treatment (e.g., opioid administration in the terminally ill) that is intended to help and not harm the patient (i.e., relieve pain) is ethically acceptable even if an unintended consequence (side effect) of its administration is to shorten the life of the patient (e.g., by respiratory depression). Under the principle of double effect, a physician may withhold or withdraw a life-sustaining therapy if the surgeon’s intent is to relieve suffering, not to hasten death. The classic formulation of double effect has four elements (Fig. 48-3).

Figure 48-3.

The four elements of the double effect principle: a) The good effect is produced directly by the action and not by the bad effect. b) The person must intend only the good effect, even though the bad effect may be foreseen. c) The act itself must not be intrinsically wrong, or needs to be at least neutral. d) The good effect is sufficiently desirable to compensate for allowing the bad effect.

Withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining therapy is ethically justified under the principle of double effect if the physician’s intent is to relieve suffering, not to kill the patient. Thus, in managing the distress of the dying, there is a fundamental ethical difference between titrating medications rapidly to achieve relief of distress and administering a very large bolus with the intent of causing apnea. It is important to note, however, that although the use of opioids for pain relief in advanced illness is frequently cited as the classic example of the double effect rule, opioids can be used safely without significant risk. In fact, if administered appropriately, in the vast majority of instances the rule of double effect need not be invoked when administering opioids for symptom relief in advanced illness.28

In accepting the ethical equivalence of withholding and withdrawing of life-sustaining therapy, surgeons can make difficult treatment decisions in the face of prognostic uncertainty.24 In light of this, some important principles to consider when considering withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy include: (a) Any and all treatments can be withdrawn. If circumstances justify withdrawal of one therapy (e.g., IV pressors, antibiotics), they may also justify withdrawal of others; (b) Be aware of the symbolic value of continuing some therapies (e.g., nutrition, hydration) even though their role in palliation is questionable; (c) Before withdrawing life-sustaining therapy, ask the patient and family if a spiritual advisor (e.g., pastor, imam, rabbi, or priest) should be called; and (d) Consider requesting an ethics consult.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree