According to the Code of Medical Ethics of the

American Medical Association (2008 to 2009),

ethical conduct for physicians is a standard based on moral principles or practices and matters of social policy involving moral issues. In contrast,

legal conduct is behavior that conforms to written law and to the regulations that interpret and set standards for such law. Unethical conduct and illegal conduct involve behavior that does not conform to these standards.

Legal and ethical principles are closely associated, although ethical standards characteristically exceed legal obligations. For example, if a physician refuses to treat a patient because the patient cannot pay for the treatment, the physician’s behavior is legal but may be deemed unethical. Although there is no legal duty for a doctor to treat most patients and thus no civil cause of action in a court of law, this doctor could face professional discipline by her peers in the form of censure or other action by her local or state medical society or board. Because since 1998, HIV-positive patients have been entitled to protection under the Americans with Disabilities Act, a doctor’s choice not to treat such a patient is now not only unethical, but is also illegal.

Certain behavior by physicians may not be illegal or unethical but may still be inappropriate. For example, accepting expensive gifts (those that can potentially be sold) from patients or treating close family members (see below), while inappropriate, do not necessarily constitute unethical behavior.

• PROFESSIONAL BEHAVIOR

Doctors are expected to observe the law and to show appropriate and professional (i.e., ethical) behavior when interacting with patients. The professional behavior of a doctor may come into question if he or she treats patients while not functioning normally, crosses boundaries in the doctor-patient relationship, or does not follow the standards of care of the community.

Impaired physicians

It is always unethical and in some circumstances illegal for physicians or physicians-in-training to practice medicine when their judgment or abilities are impaired. Causes of impairment include drug or alcohol abuse, physical or mental illness, and impairment in functioning associated with old age. If a physician is impaired, the doctor must immediately and voluntarily remove himself or herself from contact with patients.

If an impaired doctor continues to have contact with patients, colleagues with knowledge of the impairment have the responsibility to prevent that doctor from practicing medicine and to obtain help for the doctor. Colleagues also need to ensure that the impaired doctor does not see patients before getting help, and that he or she does, in fact, seek and receive appropriate treatment.

How and where to report impaired colleagues varies by the venue in which the threat occurs and by the nature of the threat. If the impairment or unethical conduct by a physician or physician-in-training threatens the welfare of hospitalized patients, it should be reported to the authorities overseeing the clinical situation (e.g., the hospital’s chief of the medical staff). An impaired medical student should be reported to the dean of the medical school or the dean of students, and an impaired resident should be reported to his or her residency training director.

If the behavior by the impaired colleague violates state licensing laws, it should also be reported to the state licensing board or to the impaired physicians program, usually part of the state medical society. If the unethical conduct violates criminal statutes, it must be reported to law enforcement agencies.

Medical malpractice

Medical malpractice occurs when a patient is harmed because of a physician’s actions or inactions. Medical malpractice is a tort, or civil wrong, not a crime. Therefore, a finding for the plaintiff (the patient) results in a financial award or damages to the patient from the defendant physician or his or her insurance carrier. Such a finding does not typically result in a jail term or loss of license for the physician.

For a malpractice claim to be substantiated, the four “D”s of malpractice must be present— dereliction, duty, damages, and directly. First, there must be negligence, or dereliction, where the doctor deviated from the normal standards of care for that community. Second, there must be an established physician-patient relationship (i.e., a duty). Generally, making an appointment with an individual constitutes establishment of such a relationship. Third, the patient must be injured (damaged), and finally, the injury must be caused directly by the doctor’s negligence, not by another factor.

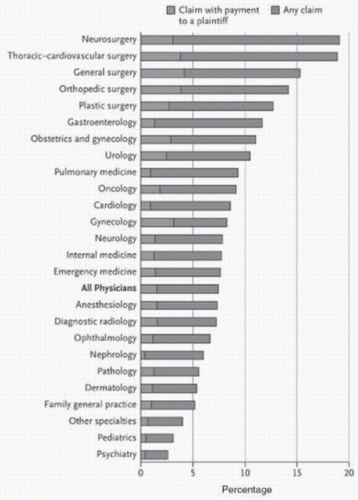

Because the invasive nature of their intervention may potentially cause physical injury to patients, physicians in high-risk specialties such as those in surgery, obstetrics, and emergency medicine are the specialists most likely to be sued for malpractice. Specialists who use few if any invasive procedures, such as psychiatrists and family practitioners, are much less likely to be sued (

Figure 26-1).

Physician error (an unintended act or omission) must be disclosed to the patient. If a doctor makes such an error, the risk of a malpractice suit can be reduced by prompt, full disclosure. For example, if a patient has an allergic reaction to medication because the prescribing physician did not check the patient’s history for allergies, the doctor should disclose this mistake to the patient and apologize. If a physician has knowledge that another doctor made such an error, the physician should encourage the other doctor to disclose it. An effective way to ensure such disclosure is for the physician to arrange a joint meeting between herself, the treating doctor, and the patient or related persons (

Wu, 1997).

When a jury finds for the plaintiff in a malpractice case, the patient can be awarded compensatory damages only or both compensatory and punitive damages. Compensatory damages are funds given to reimburse the patient for medical bills or lost salary and to compensate the patient for pain and suffering. Punitive (or exemplary) damages are designed to punish the physician and set an example for the medical community. These are awarded only in cases of wanton carelessness or gross negligence. For example, if a surgeon impaired by alcohol cuts a vital nerve leaving a patient permanently paralyzed, punitive damages may be awarded in addition to compensatory damages. Although compensatory damages are covered by most medical malpractice insurance carriers, the physician himself is responsible if punitive damages are awarded to a patient.

In recent years, the number of malpractice suits has increased, for several reasons. First, there is a general increase in lawsuits and in the size of pay outs to successful plaintiffs in malpractice actions (

Smarr, 2003). Second, a breakdown has occurred in the traditional physician-patient relationship. The latter has occurred in part because the growth of managed care and similar systems has reduced the amount of time a doctor can spend with an individual patient. In addition, technological advances in medicine have reduced the amount of personal contact that patients have with their doctors. This increase in lawsuits and awards has caused some malpractice carriers to exit from the market and the cost of malpractice insurance to rise, making it

difficult for physicians, particularly those in highrisk specialties, to obtain affordable insurance. In some states, high insurance premiums have forced some physicians to give up the practice of medicine (

Mello et al., 2003) and have compelled groups of others to press for caps on malpractice awards using formal protests and work stoppages (

Margolin & Schuppe, 2003).

Professional boundaries

No matter what behavior a patient shows toward the doctor, it is the doctor’s responsibility to maintain a professional separation or boundary between herself and the patient (

Gabbard & Nadelson, 1995). For this reason, a physician should not treat herself, family members, or close friends. However, such treatment is not ethically or legally proscribed.

Sometimes an ill patient will behave in sexually inappropriate ways toward a physician (see

Chapter 24). Although patients who act seductive may genuinely be attracted to the doctor, more commonly their behavior is caused by unconscious transference reactions or use of inappropriate defense mechanisms to deal with feelings of vulnerability, dependence, and fear associated with their illness (see

Chapter 8).

Doctors can also be attracted to their patients. However, because of the inherent inequality of the doctor-patient relationship, romantic or sexual relationships with current or even former patients are inappropriate and are prohibited by the ethical standards of most specialty boards. Patients who claim that they had a sexual relationship with a physician can file an ethics complaint, a medical malpractice complaint, or both. Similarly, sexual relationships between physicians and either patients’ relatives or the physicians’ trainees are not appropriate.

Doctors should also avoid socializing outside of the medical setting with any patient who might misinterpret such contact. In a similar way, accepting valuable gifts (e.g., jewelry) from patients is not appropriate, although it may be appropriate to accept a small token of appreciation from a patient, such as eggs produced by home-raised chickens.

If for an appropriate reason (e.g., because the doctor is retiring or relocating), a doctor wishes to or must terminate a relationship with a patient she must give notice to the patient or to family members in sufficient time to allow the patient and family to obtain the services of another doctor.

Good Samaritan laws

Physicians are not legally required to treat patients in emergencies, but those who do are shielded from the liability of malpractice suits by statutes known as Good Samaritan laws. To be shielded by these laws, the Samaritan doctor’s action in the emergency must meet certain criteria. First, the procedure that the doctor uses must be standard and generally accepted by the medical profession. Second, the actions taken by the physician must be within his or her competence and training, and the doctor cannot be paid for the emergency services. Finally, the doctor usually must stay with the patient until another physician, not paramedic personnel, take over the patient’s care.

• LEGAL COMPETENCE

To be legally competent to make health care decisions, a patient must understand the risks, benefits, and likely outcomes of such decisions (

Appelbaum, 2007). All adults (persons 18 years of age and older) are assumed to be legally competent to make health care decisions for themselves except if they are actively psychotic, suicidal, or in a coma. Minors (persons younger than 18 years) usually are not considered legally competent.

Emancipated minors

Emancipated minors are under 18 years of age but are considered competent adults and thus can make decisions concerning their own medical care. To be considered emancipated, a minor usually must fulfill at least one of the following requirements. He or she must be (1) self-supporting; (2) in the military; or (3) married. Minors are also considered emancipated if they (4) have children whom they care for, although in most states, simply being pregnant or giving birth does not automatically confer emancipation.

Questions of competence

A person can meet the legal standard for competence to accept or refuse medical treatment even if she is mentally ill or disabled or is incompetent in other areas of her life. For example, a person who has schizophrenia may be competent to make health care decisions but not be competent to manage his or her own finances.

If doubt exists, a judge must decide whether an individual is or is not competent. Physicians are often consulted by judges for information about whether patients have the capacity to make health care decisions, but physicians cannot decide whether someone is legally competent. If a person is found to be incompetent, the judge appoints a legal guardian to make decisions for that person.

Involuntary hospitalization

In psychiatric emergencies, patients who will not or cannot agree to be hospitalized can be hospitalized against their will or without consent with the certification of one or two physicians for up

to a few months (depending on state law) before a court hearing. For involuntary hospitalization, a patient usually must be

dangerous to self or others or unable to provide self-care (not merely self-neglect). Even if a psychiatric patient voluntarily chooses to be hospitalized, he may be required to wait for up to a few days (depending on state laws) before he is permitted to sign out against medical advice.

Patients who are confined to mental health facilities, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, retain most of their civil rights, including the right to receive or refuse treatment (e.g., medication, electroconvulsive therapy, and surgical procedures). However, if the patient is suicidal or psychotic (see

Chapter 12), he or she may not be considered competent to refuse treatment. In addition, medication may be administered against such patients’ wishes to prevent danger to themselves or to others.

The Mental Health Bill of Rights for confined patients can be found in

Table 26-1.

Criminal law

A crime requires both an evil intent (mens rea) and an evil deed (actus reus). For example, if a postpartum woman murders her infant because she explains “Satan told me to kill the child,” she has committed an evil deed but did not have evil intent. A judge or jury may determine that by virtue of her mental state, the woman lacked the requisite state of mind to have committed a crime.

Every adult is presumed competent to stand trial (even persons with intellectual disability or mental illness). An adult is determined unfit to stand trial (legally incompetent) if she does not understand the charges against her or is not able to cooperate with counsel in the preparation of her defense.

A person who is found legally insane must have a mental illness, and as a result of this illness must meet one of the statutory criteria (

Table 26-2) under state or federal law. Most states and federal jurisdictions have a different and more liberal set of standards under which an individual with mental illness can qualify for

diminished capacity, which may modify the punishment.

• INFORMED CONSENT

Except for life-threatening emergencies in which the patient is unconscious or otherwise incapable of consenting or in which risk disclosure is so psychologically threatening that it is medically contraindicated, physicians must obtain consent from competent, adult patients before proceeding with any medical or surgical treatment. However, before patients can consent, they must be informed of and understand several things (see later text). This combination of information provided by the physician and acquiescence by the patient is called informed consent. Although a signature may not be required for minor medical procedures, patients usually sign a document of consent for major medical procedures or for surgery. Other hospital personnel, such as nurses, usually cannot obtain informed consent.

Components of informed consent

Before patients can give consent to be treated by a doctor, they must be informed of and understand

the health implications of their diagnosis

the health risks and benefits of the treatment or procedure

the alternatives to the treatment or procedure

the likely outcome if they do not consent to the treatment or procedure

that they can withdraw consent at any time before or during the treatment or procedure

Refusal to consent

Competent patients have the right to refuse to consent to a needed test or procedure for religious or other reasons, even if their health will suffer or death will result from such refusal.

However, before accepting the patient’s refusal, the doctor should try to understand the reason behind it. If the refusal is the result of depression, fear, pain, or intolerance of the treatment, the physician should treat the depression or attempt to make the treatment more effective and acceptable to the patient (see

Chapter 25). If these steps have been taken and the patient still refuses intervention, the physician must follow the patient’s wishes.

Like other competent patients, pregnant women have the right to refuse diagnostic (e.g., fetal monitoring), medical (e.g., vitamin therapy), or surgical (e.g., cesarean section) intervention necessary to protect the health or life of the fetus, even if the fetus will die or be seriously injured without the intervention (

Case 26-1).