Esophageal Resection: Esophagogastrectomy and the Ivor Lewis Approach

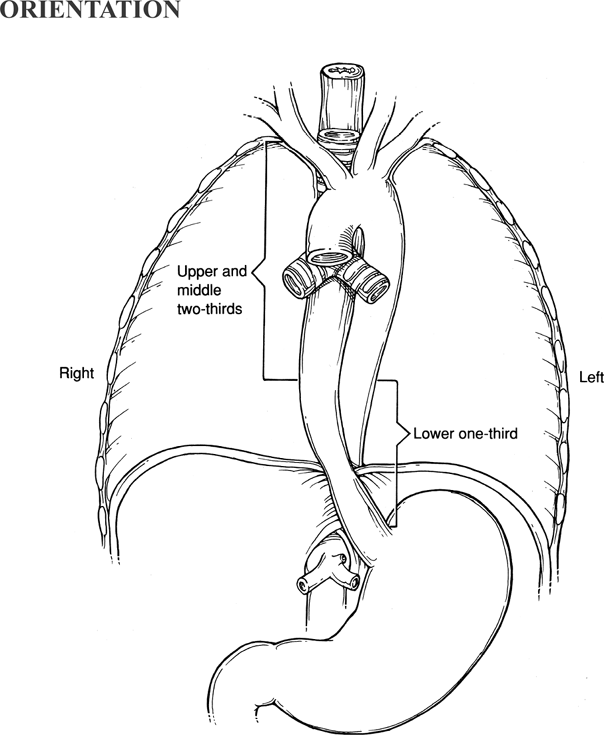

Lesions of the lower to middle third of the esophagus are approached through a thora-cotomy in conjunction with laparotomy. The lower esophagus is easily reached through the left chest, but the middle esophagus is inaccessible through this approach. Esophagogastrectomy (resection of the lower esophagus and upper stomach) is employed for carcinoma of the cardioesophageal junction. Lesions that extend above this level are better managed by an Ivor Lewis (laparotomy and right thoracotomy) type of resection, which provides access to the entire thoracic esophagus. Alternative surgical approaches, such as esophagectomy without thoracotomy and minimally invasive esophagectomy, are described in subsequent chapters and in the references.

Steps in Procedure

Esophagogastrectomy

Left thoracoabdominal incision (begin with abdominal portion and thorough exploration)

Mobilize stomach by creating window along greater curvature

Retain blood supply to greater and lesser curvature

Perform pyloromyotomy by creating incision across pylorus

Perform Kocher maneuver to mobilize duodenum

Reflect left lung upward and incise inferior pulmonary ligament to level of inferior pulmonary vein

Incise pleura overlying esophagus and develop flaps of pleura

Dissect tumor from mediastinum, taking adjacent lymph nodes with specimen

Place two stay sutures on proximal esophagus and divide it

Divide stomach with linear stapling device, 4.8 cartridge

Check hemostasis

Create gastrotomy and insert EEA stapler into stomach, bringing it out through anterior wall of proximal part of pouch

Place anvil in esophagus and secure with pursestring suture

Complete the stapled anastomosis

Reinforce the staple line by inkwelling the stomach over the anastomosis

Check hemostasis and place chest tubes

Close diaphragm with interrupted 3-0 figure-of-eight sutures

Tack stomach to hiatus

Pass nasogastric tube through anastomosis to region of pylorus and secure

Close thoracic and abdominal portion of incision in usual fashion

Ivor Lewis Resection

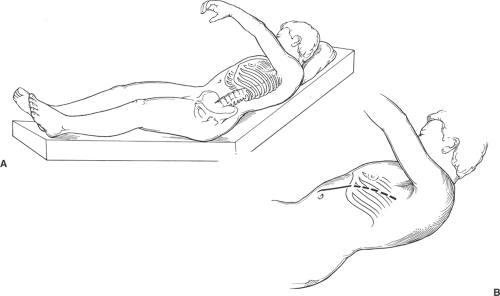

Supine position, hips flat, right chest elevated into thoracotomy position, right neck exposed

Upper midline incision, explore abdomen

Mobilize stomach as previously described

Right thoracotomy, 5th interspace

Incise pleura over esophagus

Identify azygos vein and incise overlying pleura, ligate and divide vein

Surround esophagus above tumor with Penrose drain

Carefully dissect tumor from mediastinum, including nodes with specimen

Decide whether to create anastomosis in chest or in neck

Anastomosis in Chest

Divide stomach with stapler

Place two stay sutures on proximal esophagus and divide it

Check mediastinum for hemostasis

Anastomosis and pass nasogastric tube as previously described

Tack stomach to parietal pleura

Place two chest tubes and close thoracotomy

Close laparotomy incision in usual fashion

Anastomosis in Neck

Expose cervical esophagus and mobilize it

Connect neck field with thoracotomy field by following esophagus down into chest

Divide esophagus in neck

Hand sew two-layer anastomosis of stomach to esophagus

Place two chest tubes and close thoracotomy

Place small Penrose drain in cervical incision and close incision

Close laparotomy incision without drainage

Hallmark Anatomic Complications

Injury to phrenic nerve (diaphragmatic incision)

Injury to azygos vein

Anastomotic leak

Injury to membranous portion of trachea

List of Structures

Esophagus

Diaphragm

Phrenic nerve

Internal Thoracic (Mammary) Artery

Musculophrenic artery

Superior epigastric artery

Rectus abdominis muscle

Inferior pulmonary ligament

Inferior pulmonary vein

Stomach

Pylorus

Cardia

Short gastric vessels

Spleen

Left gastroepiploic vessels

Right gastroepiploic vessels

Gastroduodenal artery

Gastrocolic ligament

Greater omentum

Lesser omentum

Right gastric artery

Left gastric artery

Coronary vein

Inferior phrenic artery

Aorta

Azygos vein

Thoracic duct

Internal jugular vein

Sternocleidomastoid muscle

Omohyoid muscle

Middle thyroid veins

Recurrent laryngeal nerve

|

Esophagogastrectomy

Incision and Initial Exploration (Fig. 30.1)

Technical Points

Position the patient in a modified left thoracotomy position. Place the hips of the patient flat on the operating table. Raise the left shoulder and support the left arm. Ideally, the shoulders should be in an almost full thoracotomy position, while the pelvis is flat. Patients with less flexible spines may not be able to tolerate this position. In such cases, the patient’s pelvis should be allowed to rotate with the upper trunk.

Plan a thoracoabdominal incision that extends in a straight line from the eighth intercostal space to a point just above and slightly beyond the umbilicus. Mark the line of the proposed skin incision. Make your initial incision through just the abdominal portion of this incision and assess resectability of the tumor before proceeding into the chest.

Incise the fascial and muscular layers of the abdominal wall in a direct line with the incision. Use electrocautery to control bleeding as you pass through the muscular layers of the abdominal wall. Continue the skin incision up several centimeters over the costal margin, but do not yet divide the costal margin.

Assess resectability by palpating the tumor at the cardioesophageal junction and assessing its mobility. Check the liver and other intraabdominal viscera for metastatic deposits. Palpable nodes along the celiac axis do not necessarily preclude resection, which will provide the best palliation for a lesion in this area. If the lesion is believed to be resectable, extend the incision up into the chest. Divide the costal cartilage and excise a 1 cm piece of it. After opening the left chest in the eighth intercostal space and attaining hemostasis in the intercostal muscles, place a self-retaining or Finochietto-type retractor and spread the ribs.

Divide the diaphragm with a curvilinear lateral incision that is planned to avoid the phrenic nerve. Sharply divide the inferior pulmonary attachments and reflect the left lung upward. An indwelling nasogastric tube or esophageal stethoscope should be palpable in the esophagus.

Anatomic Points

When planning a thoracoabdominal incision, make sure that the thoracic part of the incision is through the appropriate intercostal space. The first rib cannot be palpated because of the clavicle; hence, one must start counting with the second rib, which articulates with the sternum at the sternal angle of Lewis. The incision should be inferior to the pectoralis major and minor muscles. As in any thoracic incision, divide the intercostal muscles along the superior margin of the lower rib to avoid the intercostal neurovascular bundle. Remember that the anterior portion of the costal margin is formed by the union of costal cartilages of the eighth through tenth ribs articulating with the cartilage of the rib above, and that the lowest costal cartilage articulating with the sternum is that of the seventh rib.

The combined thoracoabdominal incision divides the terminal branches of the internal thoracic (mammary) artery. One of these branches—the musculophrenic artery—passes inferolaterally behind the seventh to ninth costal cartilages. The other—the superior epigastric artery—is divided when the rectus abdominis muscle is divided. Both arteries have free anastomoses with other arteries.

Division of the diaphragm must take into account the location of the phrenic nerve and its three major branches. The left phrenic nerve enters the muscular part of the right hemidiaphragm just lateral to the left cardiac surface. As it traverses the diaphragm, it divides into a sternal branch that runs anteromedially toward the sternum, an anterolateral branch that passes laterally anterior to the central tendon, and a posterior branch that runs posterior to the central tendon and that supplies crural fibers to the left of the esophageal hiatus, regardless of whether the esophageal hiatus is entirely surrounded by right crus or by both left and right crura.

The mediastinal root of the pulmonary ligament is anterior to the esophagus. Division of this ligament allows the lung to be retracted superiorly, exposing the distal esophagus in the left chest. Caution must be exercised, however, because the fragile inferior pulmonary vein lies at the top of the pulmonary ligament.

Mobilization of the Stomach and Pyloromyotomy (Fig. 30.2)

Technical Points

Mobilize the stomach by creating a window along the greater curvature. The spleen may be taken with the specimen. The mobilization is essentially the same as that described for total gastrectomy (see Chapter 53). Preservation of the omentum will allow some omentum to be wrapped around the anastomosis at the conclusion of the surgery, thus ensuring a good blood supply for the stomach. Fully mobilize the stomach from the pylorus to the cardioesophageal junction.

Perform a Kocher maneuver to mobilize the duodenum. Do this by incising the peritoneum lateral to the duodenum and elevating the duodenum off the retroperitoneum by sharp and blunt dissection. This should be an avascular plane that allows the duodenum to rotate toward the midline. The head of the pancreas will come up with the duodenum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree