Endoscopic Studies

OVERVIEW OF ENDOSCOPIC STUDIES

Endoscopy is the general term given to all examination and inspection of body organs or cavities using endoscopes. These instruments can also provide access for certain kinds of surgical procedures or treatments. Endoscopes, known generally as fiberoptic instruments, are used for direct visual examination of certain internal body structures by means of a lighted lens system attached to either a rigid or flexible tube. Fiberoptic instruments transmit signals from the tip of the scope via glass or plastic threads to a TV monitor. Light travels through an optic fiber by means of multiple reflections. Fiberoptic instruments, composed of fiber bundle systems, redirect and transmit light around twists and bends in cavities and hollow organs of the body. An image fiber and a light fiber allow visualization at the distal tip of the scope. Separate ports allow instillation of drugs, lavage, suction, and insertion of a laser, brushes, forceps, or other instruments used for excision, sampling, or other diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. The flexible scope can be inserted into orifices or other areas of the body not easily accessed or directly visualized by rigid scopes or other means. Procedures are done for health screening, diagnosis of pathologic conditions, or therapy, such as removal of tissue (polyps) or foreign objects. Sedatives or analgesia (to achieve a state of conscious sedation) or local or general anesthetics may be used. The use of video documentation and endoscopic sonography (diagnostic imaging for visualizing subcutaneous body structures) also aids in cancer diagnosis, staging of cancer, and determining operability. Biopsy tissue is submitted to the laboratory for histologic examination (see Chapter 11).

Mediastinoscopy, performed under general anesthesia, requires insertion of a lighted mirror-lens instrument, similar to a bronchoscope, through an incision at the base of the anterior neck, to examine and biopsy mediastinal lymph nodes. Because these nodes receive lymphatic drainage from the lungs, mediastinal biopsy specimens can allow identification of diseases such as carcinoma, granulomatous infection, sarcoidosis, coccidioidomycosis, and histoplasmosis. Mediastinoscopy is used to stage lung tumors, diagnose sarcoidosis, biopsy mediastinal lymph nodes directly, and assess hilar adenopathy of unknown origin. It has virtually replaced scalene fat pad biopsy for examining suspicious nodes on the right side of the mediastinum. It is the routine method of establishing tissue diagnosis and staging of lung cancer and for evaluating the extent of lung tumor metastasis, done just before thoracotomy. Nodes on the left side of the chest are usually resected through left anterior thoracotomy (mediastinoscopy) or occasionally by scalene fat pad biopsy. This procedure is performed by a thoracic surgeon.

Reference Values

Normal

No evidence of disease

Normal lymph glands

Procedure

Mediastinoscopy is considered a surgical procedure and is usually performed under general anesthesia in a hospital.

Biopsy is performed through a suprasternal incision in the neck (2-3 cm or 3-4 cm), just above the sternal notch. When the Chamberlain procedure is performed, a small transverse incision is done in the second intercostal space or over the second or third costal cartilage.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed intratest care.

PROCEDURAL ALERT

PROCEDURAL ALERT

Observe standard precautions and latex precautions for all endoscopic procedures.

Some investigators and clinicians have concerns about tissue damage, immunosuppression, and site metastases after endoscopic procedures.

Endoscopically related bacteremia infections may result from tissue manipulations, bloodstream invasion by pathogens, or a contaminated endoscope, usually due to improper cleansing and disinfection. It is important that strict infection control guidelines be followed by persons who clean and disinfect the endoscopes. Hospitals and clinics should follow the infection control policies for their institution, which should include documentation of all endoscopic procedures, including name of patient, type of procedure, date and time of procedure, and serial number of the endoscope used in each procedure. A log documenting the time, date, and serial number of each endoscope cleaned and disinfected should also be maintained. These records allow for tracing an infection back to a specific instrument. Any infections suspected to have been caused by a contaminated instrument should be reported immediately to the appropriate infection control and risk management departments for investigation.

Clinical Implications

Abnormal findings may include the following conditions:

Sarcoidosis (chronic inflammatory cell accumulation in multiple organs)

Tuberculosis

Histoplasmosis (disease caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum)

Hodgkin’s disease (cancer of the lymphatic system)

Granulomatous infections and inflammatory processes

Carcinomatous lesions

Coccidioidomycosis

Pneumocystis carinii infection

Results assist in defining the extent of metastatic process, staging of cancer (N2 and N3, IIIa and IIIb), and possibility of successful surgical resectability.

Interventions

Pretest Patient Care

Explain the purpose, procedure, benefits, and risks of the test. It is usually used after computed tomography (CT) scan and indicates enlarged mediastinal nodes (> 1 cm).

A legal surgical consent form must be appropriately signed and witnessed preoperatively (see Chapter 1).

Remember that preoperative care is the same as that for any patient undergoing general anesthesia and surgery.

Have the patient fast for 8 or more hours before the test.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Posttest Patient Care

Care is the same as for any patient who has had surgery under general anesthesia.

Evaluate breathing and lung sounds; check wound for bleeding and hematoma.

At time of discharge, monitor for complications (e.g., breathing difficulties, coughing up blood). Instruct the patient to call physician if problems occur.

After endoscopic procedures, assess for fever, elevated white blood cells, signs of bloodstream infection, and signs of sepsis (rigors and hypotension, hypothermia or hyperthermia).

Interpret test outcomes, monitor appropriately, and explain any need for follow-up tests or treatment (e.g., medication for tuberculosis, antibiotics).

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Previous mediastinoscopy contraindicates repeat examination because adhesions make satisfactory dissection of nodes extremely difficult or impossible.

Complications can result from the risks associated with general anesthesia and from preexisting conditions, pneumothorax, and subcutaneous emphysema.

Damage to major vessels can occur during this procedure.

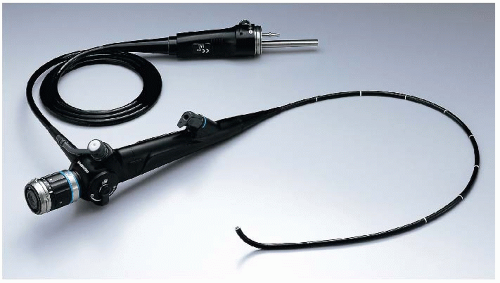

Bronchoscopy permits visualization of the trachea, bronchi, and select bronchioles. There are two types of bronchoscopy: flexible (Fig. 12.1), which is almost always used for diagnostic purposes, and rigid, which is less frequently used. This procedure is done to diagnose tumors, coin lesions, or granulomatous lesions; to find hemorrhage sites; to evaluate trauma or nerve paralysis; to obtain biopsy specimens; to take brushings for cytologic examinations; to improve drainage of secretions; to identify inflammatory infiltrates; to lavage; and to remove foreign bodies. Bronchoscopy can determine resectability of a lesion as well as provide the means to diagnose bronchogenic carcinoma. A transbronchial needle biopsy may be performed during this procedure, thus obviating the need for diagnostic open-lung biopsy. A flexible needle is passed through the trachea or bronchus and is used to aspirate cells from the lung. This procedure is performed on patients with suspected sarcoidosis or pulmonary infection.

Indications for the Test

Diagnostic:

Staging of bronchogenic carcinoma

Differential diagnosis in recurrent unresolved pneumonia

FIGURE 12.1. Fiberoptic bronchoscope (Olympus BF Type P60). (Image courtesy of Olympus America Inc.)

Evaluation of cavitary lesions, mediastinal masses, and interstitial lung disease

Localization of bleeding and occult sites of cancer

Evaluate immunocompromised patients (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]-infected patients, bone marrow or lung transplant recipients)

Differentiate rejection from infection in lung transplantation

Assess airway damage in thoracic trauma

Evaluate underlying etiology of nonspecific symptoms of pulmonary disease such as chronic cough (> 6 months), hemoptysis, or unilateral wheezing

Therapeutic:

Removal of mucus plugs and polyps

Removal of an aspirated foreign body and to relieve endobronchial obstruction

Brachytherapy (radioactive treatment of malignant endobronchial tumors)

Placement of a stent (mesh-like tube) to maintain airway patency

Drainage of lung abscess

Decompression of bronchogenic cysts

Laser photoresection of endotracheal lesions

Bronchoalveolar lavage to remove intra-alveolar proteinaceous material

Alternative to difficult endotracheal intubations

Control bleeding and airway hemorrhage in the presence of massive hemoptysis

The examination is usually done under local anesthesia combined with some form of sedation in an outpatient setting, diagnostic center, or operating room. It also can be done in a critical care unit, in which case the patient may be unresponsive or ventilator dependent.

Reference Values

Normal

Normal trachea, bronchi, nasopharynx, pharynx, and select bronchioles (conventional bronchoscopy cannot visualize alveolar structures)

Procedure

Spray and swab topical anesthetic (e.g., 4% lidocaine) onto the back of the nose, the tongue, the pharynx, and the epiglottis. Give an antisialagogue (e.g., atropine) to reduce secretions. If the patient has a history of bronchospasms, administer a bronchodilator (e.g., albuterol) through a handheld nebulizer. Morphine sulfate is contraindicated in patients who have problems with bronchospasm or asthma because it can cause bronchospasm. Analgesics, barbiturates, tranquilizer-sedatives, and atropine may be ordered and administered 30 minutes to 1 hour before bronchoscopy. The patient should be as relaxed as possible before and during the procedure but also needs to know that anxiety is normal.

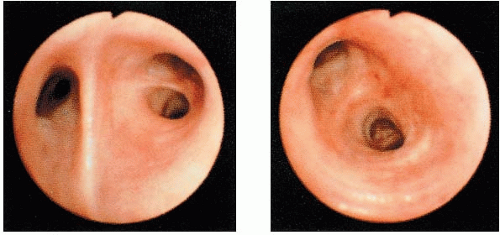

Insert the flexible or rigid bronchoscope carefully through the mouth or nose into the pharynx and the trachea (Fig. 12.2). The scope also can be inserted through an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy. Suctioning, oxygen delivery, and biopsies are accomplished through bronchoscope ports designed for these purposes.

Be advised that because of sedation, usually with diazepam (Valium) or midazolam (Versed), the patient is usually comfortable when a state of conscious sedation is achieved. However, when the bronchoscope is advanced, some patients may feel as if they cannot breathe or are suffocating.

Arterial blood gas measurement during and after bronchoscopy may be ordered, and arterial blood oxygen may remain altered for several hours after the procedure (see Chapter 14). Sputum specimens taken during and after bronchoscopy may be sent for cytologic examination or culture and sensitivity testing. These specimens must be handled and preserved according to institutional protocols (see Chapter 16).

Continuous monitoring of electrocardiogram (ECG), blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and respirations is routinely performed. Monitoring of pulse oximetry is especially important to indicate levels of oxygen saturation before, during, and after the procedure.

The right lung, by convention, is normally examined before the left lung.

Bronchoscopic procedures include any one or a combination of the following:

Bronchial washings for cytology and staining for fungi and mycobacteria

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) for infectious (e.g., alveolar proteinosis, eosinophilic granuloma) diseases

Bronchial brushings of both visible and peripheral (under fluoroscopy) endobronchial lesions or transbronchial biopsies, both visible and peripheral

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed intratest care.

PROCEDURAL ALERT

PROCEDURAL ALERTBronchoscopy instruments can decrease an already small airway lumen even more by causing inflammation and edema. Consequently, a child can rapidly become hypoxic and desaturate oxygen very quickly. Resuscitation, oxygen administration equipment, and drugs must be readily accessible when this procedure is performed on a child. Close monitoring of respiratory and cardiac status is imperative during and after the procedure. The same precautions and treatment apply to children and adults. Most children suffer cardiac arrest because of respiratory problems, not cardiac problems.

Clinical Implications

Abnormalities revealed through bronchoscopy include the following conditions:

Abscesses

Bronchitis

Carcinoma of the bronchial tree (occurs in the right lung more often than the left)

Tumors (usually appear more often in larger bronchi)

Tuberculosis

Alveolitis

Evidence of surgical nonresectability (e.g., involvement of tracheal wall by tumor growth, immobility of a main-stem bronchus, widening and fixation of the carina)

Pneumocystis carinii infection

Inflammatory processes

Cytomegalovirus infection

Aspergillosis

Idiopathic nonspecific pulmonary fibrosis

Cryptococcus neoformans infection

Coccidioidomycosis

Histoplasmosis (disease caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum)

Blastomycosis (fungal infection caused by inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis)

Phycomycosis (group of fungal diseases caused by Phycomycetes)

Clinical Considerations

The following data must be available before the procedure: history and physical examination, recent chest x-ray film, recent arterial blood gas values, and if the patient is > 40 years of age or has heart disease, ECG. Appropriate blood work (coagulation), urinalysis, pulmonary function tests, and sputum studies (especially for acid-fast bacilli) must be done as well. Bronchoscopy is often done as an ambulatory surgical procedure.

Interventions

Pretest Patient Care

Reinforce information related to the purpose, procedure, benefits, and risks of the test. Record signs and symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, bloody sputum, coughing, hoarseness).

Emphasize that pain is not usually experienced because lungs do not have pain fibers.

Explain that the local anesthetic may taste bitter, but numbness will occur in a few minutes. Feelings of a thickened tongue and the sensation of something in the back of the throat that cannot be coughed out or swallowed are not unusual. These sensations will pass within a few hours following the procedure as the anesthetic wears off.

Informed consent form must be properly signed and witnessed (see Chapter 1).

Have the patient fast for at least 6 hours before the procedure to reduce the risk for aspiration. Gag, cough, and swallowing reflexes will be blocked during and for a few hours after surgery.

Ensure that the patient removes wigs, nail polish, makeup, dentures, jewelry, and contact lenses before the examination.

Use techniques to help the patient relax and breathe more normally during the procedure. The more relaxed the patient is, the easier it is to complete the procedure.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Contraindications to bronchoscopy include the following conditions:

Severe hypoxemia

Severe hypercapnia (carbon dioxide retention)

Certain cardiac arrhythmias, cardiac states

History of being hepatitis B carrier

Bleeding or coagulation disorders

Severe tracheal stenosis

Posttest Patient Care

Swallowing, gagging, and coughing reflexes should be present before allowing food or liquids to be ingested orally. Usually the patient has fasted for at least 2 hours before the procedure.

Provide gargles to relieve mild pharyngitis. Monitor ECG, blood pressure, temperature, pulse, pulse oximeter readings, skin and nail bed color, lung sounds, and respiratory rate and patterns according to institution protocols. Document observations.

The following may be ordered:

Oxygen by mask or nasal cannula. Humidified oxygen at specific concentrations up to 100% by mask may be necessary.

A chest x-ray film. This will check for pneumothorax or to evaluate the lungs.

Sputum specimens. These must be preserved in the proper medium or solution.

Elevate the head of the bed for comfort.

Interpret test outcomes, monitor appropriately, and explain need for other tests or treatment. Follow-up procedures may be necessary. CT-guided fine-needle cytology aspiration may be done when bronchoscopy is not diagnostic.

Do not allow the patient to drive or sign legal documents for 24 hours because of the effects of anesthetics and sedation.

Refer to intravenous sedation precautions in Chapter 1.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Observe for possible complications of traditional bronchoscopy, which may include the following conditions:

Shock

Bleeding following biopsy (rare, but can occur if there is excessive friability of airways or massive lesions, or if patient is uremic or has a hematologic disorder)

Hypoxemia

Partial or complete laryngospasm (inspiratory stridor) that produces a “crowing” sound; may be necessary to intubate

Bronchospasm (pallor and increasing dyspnea are signs)

Infection or gram-negative bacterial sepsis

Pneumothorax

Respiratory failure

Cardiac arrhythmias

Anaphylactic reactions to drugs

Seizures

Febrile state

Hypoxia, respiratory distress

Empyema (accumulation of pus in the lung pleura)

Aspiration

Virtual noninvasive bronchoscopy using spiral CT technology requires no sedation or analgesics. Indications include pulmonary embolism and staging of lung cancer.

Thoracoscopy is an examination of the thoracic cavity using an endoscope. Video-assisted thoracoscopy (VAT) is a recent addition to the procedures available for diagnosing intrathoracic diseases. This procedure is making a comeback because it can be used as a diagnostic device when other methods of diagnosis fail to present adequate and accurate findings. Moreover, the discomfort and many of the risks associated with traditional diagnostic thoracotomy procedures are reduced with thoracoscopy. Thoracoscopy allows visualization of the parietal and visceral pleura, pleural spaces, thoracic walls, mediastinum, and pericardium without the need for more extensive procedures. It is used most frequently to investigate pleural effusion and can be used to perform laser procedures; diagnose and stage lung disease; assess tumor growth, pleural effusion, emphysema, inflammatory processes, and

conditions predisposing to pneumothorax; and perform biopsies of pleura, mediastinal lymph nodes, and lungs.

conditions predisposing to pneumothorax; and perform biopsies of pleura, mediastinal lymph nodes, and lungs.

Reference Values

Normal

Thoracic cavity and tissues normal and free of disease

Procedure

Thoracoscopy is considered an operative procedure. The patient’s state of health, the particular positioning needed, and the procedure itself determine the need for either local or general anesthesia. The incision is usually made at the midaxillary line and the sixth intercostal space.

Schedule admission the morning of the procedure. Many patients are discharged the following day, provided the lung has reexpanded properly and chest tubes have been removed.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed intratest care.

Clinical Implications

Abnormal findings can include the following conditions:

Carcinoma or metastasis of carcinoma

Empyema (accumulation of pus in the lung pleura)

Pleural effusion

Conditions predisposing to pneumothorax or ulcers

Inflammatory processes

Bleeding sites

Tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, or histoplasmosis

Interventions

Pretest Patient Care

Reinforce and explain the purpose, procedure, benefits, and risks of the examination and describe what the patient will experience. Record preprocedure signs and symptoms.

A surgical consent form must be appropriately signed and witnessed before the procedure begins (see Chapter 1).

Complete and review required blood tests, urinalysis, recent chest x-ray film, and ECG (for certain individuals) before the procedure.

Have the patient fast for 8 hours before the procedure.

Insert an intravenous line for the administration of intraoperative intravenous fluids and intravenous medication.

Perform skin preparation and correct positioning in the operating room.

Place a chest tube and connect to negative suction or sometimes to gravity change after the thoracoscopy is completed.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Posttest Patient Care

Take a postoperative chest x-ray film to check for abnormal air or fluid in the chest cavity.

Monitor vital signs, amount and color of chest tube drainage, fluctuation of fluid in the chest tube, bubbling in the chest drainage system, and respiratory status, including arterial blood gases. Promptly report abnormalities to the physician.

Administer pain medication as necessary. Encourage relaxation exercises as a means to lessen the perception of pain. Monitor quality and rate of respirations. Be alert to the possibility of respiratory depression related to narcotic administration or intrathecal narcotics.

Encourage frequent coughing and deep breathing. Assist the patient in splinting the incision during coughing and deep breathing to lessen discomfort. Promote leg exercises while in bed and assist with frequent ambulation if permitted.

Use open-ended questions to provide the patient with an opportunity to express concerns.

Document care accurately.

Interpret test outcomes and monitor appropriately.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed posttest care. Provide written discharge instructions.

Do not clamp chest tubes unless specifically ordered to do so. Clamping chest tubes may cause tension pneumothorax. Sudden onset of sharp pain, dyspnea, uneven chest wall movement, tachycardia, anxiety, and cyanosis may indicate pneumothorax. Notify the physician immediately.

Possible wound and pulmonary complications include the following:

Acute respiratory distress, hypoxia

Infection

Hemorrhage (watch for unusually large outputs of blood in a relatively short period of time into the chest drainage system and notify physician immediately)

Empyema (accumulation of pus in the lung pleura)

Atelectasis

Aspiration

Nerve damage may occur during the procedure.

Endoscopy is a general term for visual inspection of any body cavity with an endoscope. Endoscopic examination of the upper gastrointestinal (UGI) tract (mouth to upper jejunum) is referred to when the following examinations are ordered: panendoscopy, esophagoscopy, gastroscopy, duodenoscopy, esophagogastroscopy, or esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy allows direct visualization of the interior lumen of the upper gastrointestinal tract with a fiberoptic instrument designed for that purpose. EGD is indicated for patients with dysphagia; reflux symptoms; weight loss; hematemesis; melena; persistent nausea and vomiting; persistent epigastric, abdominal, or chest pain; and persistent anemia. EGD can confirm suspicious x-ray findings and establish a diagnosis in symptomatic patients with negative x-ray reports. EGD can be used to diagnose and treat many abnormalities of the UGI tract, including hernias, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), esophagitis, gastritis, strictures, varices, ulcers, polyps, and tumors. It can be used to remove foreign bodies (e.g., a swallowed coin in a small child) and for placement of a percutaneous gastric or duodenal feeding tube. For patients who require some form of UGI surgery, it provides a safe way to perform presurgical screening and postsurgical surveillance.

Reference Values

Normal

UGI tract within normal limits

Procedure

Remember that this examination is usually performed in an outpatient setting of a hospital or ambulatory clinic. It also may be performed in the operating room or in a critical care setting.

Use a topical spray to anesthetize the patient’s throat.

Start an intravenous line and use for administration of sedation alone or in combination with analgesics. These medications are given to achieve a state of conscious sedation. Resuscitation equipment must be available.

Perform continuous monitoring of the patient’s vital signs, ECG, and oxygen saturation (pulse oximetry).

Remove partial dental plates or dentures. Insert a mouthpiece to prevent the patient from biting the endoscope and to prevent injury to the patient’s teeth, tongue, or other oral structures.

Lubricate the endoscope well. Gently insert through the mouthpiece into the esophagus and advance slowly into the stomach and duodenum. Insufflate air through the scope to distend the area being examined so that optimal visualization of the mucosa is possible. Obtain tissue biopsy specimens and brushings for cytology. Take photos to provide a permanent record of observations.

Inform the patient that he or she may have an initial gagging sensation that quickly subsides. During the procedure, the patient may belch frequently. Sensations of abdominal pressure or bloating are normal, but the patient should not experience actual pain.

Immediately after the examination is completed, ask the patient to remain on his or her left side until fully awake.

Clinical Implications

Abnormal results may indicate the following conditions:

Hemorrhagic areas or erosion of an artery or vein

Hiatal hernia

Esophagitis, gastritis

Neoplastic tissue

Gastric ulcers (benign or malignant)

Esophagitis, gastritis, duodenitis

Esophageal or gastric varices

Esophageal, pyloric, or duodenal strictures

Interventions

Pretest Patient Care

Explain the purpose and procedure of the examination, the sensations that may be experienced, and the benefits and risks of the test. Refer to intravenous conscious sedation precautions in Chapter 1. Reassure the patient that the endoscope is thinner than most food swallowed. Inform the patient that he or she may be quite sleepy during the EGD and may not recall much or any of the experience. Record preprocedure signs and symptoms (e.g., vomiting, melena (black, tarry feces), dysphagia, and persistent upper GI pain).

Patients should be instructed to fast before the procedure, according to the hospital or clinic policy. Generally, adult patients should fast 6 to 8 hours before the examination, and children may have clear liquids up until 2 hours before the procedure; however, each patient should be assessed on an individual basis, according to age, size, and general health status. Inpatients may have intravenous fluids to prevent dehydration. Outpatients need education about potential risks for aspiration and possible cancellation of the procedure if fasting is not maintained.

Confirm informed consent. A legal consent must be signed and witnessed before the procedure.

Encourage the patient to urinate and defecate if possible before the examination.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Posttest Patient Care

Do not permit food or liquids until the patient’s gag reflex returns.

Monitor blood pressure, pulse, respirations, and oxygen saturation according to the hospital or clinic policy, usually every 15 to 30 minutes, until the patient is fully awake.

Ask the patient to remain on his or her left side with side-rails raised until fully awake. This position usually prevents aspiration.

Encourage the patient to belch or expel air inserted into the stomach during the examination.

Remember that the patient should not experience discomfort or side effects once the sedative has worn off. Occasionally, the patient may complain of a slight sore throat. Sucking on lozenges after swallowing reflexes return may be helpful if these are permitted.

Interpret test outcomes and monitor appropriately.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed posttest care.

Complications are rare; however, the following complications can occur:

Perforation

Bleeding or hemorrhage

Aspiration

Infection

Complications from drug reaction (leading to hypotension, respiratory depression or arrest, allergic or anaphylactic response)

Complications from unrelated diseases (e.g., myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident)

Death (very rare)

Esophageal manometry measures the movement, coordination, and strength of esophageal peristalsis as well as the function of the upper and lower esophageal sphincters. The test consists of recording intraluminal pressures at various levels in the esophagus and at the upper and lower esophageal sphincters. Intraluminal pressures can be measured with the use of a manometric catheter, which is passed intranasally in the patient and then attached to an infusion pump, transducer, and recorder. The intraluminal pressures produce waveform readings (somewhat similar to ECG readings), which can be used to assess esophageal function.

Indications for the Test

Abnormal esophageal muscle function

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

Heartburn

Noncardiac chest pain

Regurgitation

Vomiting

Esophagitis

Another test, often done in conjunction with manometry, is the Bernstein test (discussed later). This procedure is useful for evaluating heartburn, esophagitis, and noncardiac chest pain.

Reference Values

Normal

Normal esophageal and stomach pressure readings

Normal contractions

No acid reflux

Procedure

Remember that the examination is usually performed in an outpatient setting, such as an ambulatory clinic or physician’s office.

Attach the manometric catheter to the infusion pump. Set up the transducer and recording equipment and calibrate according to manufacturer’s recommendations.

Assess the patient’s nasal passage for adequate size and patency. Generously apply a topical anesthetic to the selected nostril.

Lubricate the manometric catheter and pass it through the nostril, down the esophagus, and just below the lower esophageal sphincter with the patient in a sitting position. Facilitate this with the patient drinking sips of water through a straw.

Begin recording. Pull the catheter through the lower esophageal sphincter, then the esophageal body, and finally the upper esophageal sphincter. Different techniques may be used to obtain recordings. The patient may be asked to swallow, not swallow, take sips of water, or hold his or her breath while the catheter is pulled through.

The Bernstein test evaluates for acid reflux by means of a nasogastric tube passed to a point 5 cm above the gastroesophageal junction. Concentration of hydrochloric acid (0.1 normal HCl) is infused for 10 minutes into the esophagus to reproduce symptoms of heartburn or chest discomfort. In the first 5 minutes of testing, 0.9% sodium chloride (NaCl) is infused as a control. Testing takes about 15 minutes. The patient may lie down or sit up.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed intratest care.

Clinical Implications

Abnormal recordings reveal the following conditions:

Primary esophageal motility disorders, such as achalasia, nutcracker esophagus, or diffuse esophageal spasm

Hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter

Acid reflux

Interventions

Pretest Patient Care

Explain the purpose, procedure, benefits, and risks of the test.

Obtain an informed consent that is properly signed and witnessed.

Confirm that the patient has fasted for 6 hours before testing.

Instruct the patient on the techniques of swallowing, sipping water, and so forth to facilitate accurate recordings.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 regarding safe, effective, informed pretest care.

Posttest Patient Care

Advise the patient that a sore throat and nasal passage irritation are common for 24 hours after the examination. Sensations of heartburn may also persist. Administer antacids if ordered.

Observe for or instruct patient to watch for nasal bleeding, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, or unusual pain.

Interpret test outcomes, counsel, and monitor appropriately as above.

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed posttest care. Provide written discharge instructions.

Complications are rare; however, the following can occur: aspiration; perforation of nasopharynx, esophagus, or stomach; epistaxis.

This examination of the hepatobiliary system is done through a side-viewing flexible fiberoptic endoscope by instillation of contrast medium into the duodenal papilla, or ampulla of Vater. This allows for radiologic visualization of the biliary and pancreatic ducts. It is used to evaluate jaundice, pancreatitis, persistent abdominal pain, pancreatic tumors, common duct stones, extrahepatic and intrahepatic biliary tract disease, malformation, and strictures and as a follow-up study in confirmed or suspected cases of pancreatic disease.

ERCP manometry can be done to obtain pressure readings in the bile duct, pancreatic duct, and sphincter of Oddi at the papilla. Measurements are obtained using a catheter that is inserted into the endoscope and placed within the sphincter zone.

Reference Values

Normal

Normal appearance and patent pancreatic ducts, hepatic ducts, common bile ducts, duodenal papilla (ampulla of Vater), and gallbladder

Manometry: Normal pressure readings of bile and pancreatic ducts and sphincter of Oddi

Procedure

Remember that this examination is usually performed in a hospital or outpatient setting where fluoroscopy and x-ray equipment are available.

Have the patient gargle with or spray his or her throat with a topical anesthetic.

Start an intravenous line and use for administration of sedatives and analgesics. These medications are given to achieve a state of conscious sedation. In some situations, general anesthesia may be used. Resuscitation equipment must be available.

Perform continuous monitoring of the patient’s vital signs, ECG, and oxygen saturation (pulse oximetry).

Remove partial dental plates or dentures. Insert a mouthpiece to prevent the patient from biting the endoscope and to prevent injury to the patient’s teeth, tongue, or other oral structures.

Have the patient assume a left lateral position with the knees flexed. The endoscope is well lubricated and inserted via the mouthpiece, down the esophagus and stomach, and into the duodenum. At this point, have the patient assume a prone position with the left arm positioned behind him or her.

Instill simethicone to reduce bubbles from bile secretions. Give glucagon or anticholinergic agents intravenously to relax the duodenum so that the papilla can be cannulated. (Atropine increases the heart rate.)

Pass a catheter into the ampulla of Vater and instill a contrast agent through the cannula to outline the pancreatic and common bile ducts. Perform fluoroscopy and x-rays at this time.

Take biopsy specimens or cytology brushings before the endoscope is removed.

Monitor for side effects and drug allergy reactions (e.g., diaphoresis, pallor, restlessness, hypotension).

Follow guidelines in Chapter 1 for safe, effective, informed intratest care.

Clinical Implications

Abnormal results reveal stones, stenosis, and other abnormalities that are indicative of the following conditions:

Biliary cirrhosis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Cancer of bile ducts, gallstones

Pancreatic cysts

Pseudocysts

Pancreatic tumors

Cancer of the head of the pancreas

Chronic pancreatitis

Pancreatic fibrosis

Cancer of duodenal papilla

Papillary stenosis

Peptic ulcer disease

Contraindications include:

Acute pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocysts, and cholangitis

Obstructions or strictures within the esophagus or duodenum

Acute infections

Recent myocardial or severe pulmonary disease

Coagulopathy

Recent barium x-rays of the GI tract (barium obscures views during ERCP)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree