Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Diabetes

Irene E. Schauer

Jane E.B. Reusch

Adrenal Insufficiency

What are the general categories of adrenocortical insufficiency?

Can you explain why thyroid function tests should be evaluated in a patient with primary adrenal failure?

What are the characteristic signs and symptoms of acute and chronic adrenal insufficiency?

What criteria are used to make the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency?

What are the considerations in deciding on long-term replacement therapy for Addison’s disease?

What other metabolic abnormalities may occur in association with adrenal insufficiency?

What are the events that take place in the regulation of cortisol secretion by the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis?

What are the specific causes of primary and secondary adrenal failure?

Discussion

What are the general categories of adrenocortical insufficiency?

Adrenocortical insufficiency results primarily from deficient cortisol production and in some cases deficient aldosterone and androgen production by the adrenal gland. Because the adrenal cortex is normally stimulated by pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH; corticotropin), cortisol deficiency may result from adrenal disease (primary adrenal insufficiency or Addison’s disease) or from pituitary or hypothalamic disease with ACTH deficiency (secondary adrenal insufficiency).

Can you explain why thyroid function tests should be evaluated in a patient with primary adrenal failure?

The association between autoimmune thyroiditis and autoimmune adrenal disease is well recognized. In general, patients with Addison’s disease are afflicted more frequently with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis than with Graves’ disease. Approximately 50% or more of affected patients have high titers of thyroid antimicrosomal antibodies, although these patients often have no thyroid-related symptoms. Graves’ hyperthyroidism can occur in association with primary adrenal failure. The association between thyroid failure and adrenal failure can also reflect hypopituitarism, with a consequent deficiency of both ACTH and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Therefore, abnormal results from thyroid function tests have been seen in the settings of both primary and secondary hypoadrenalism, making thyroid function tests an important component of the evaluation of a patient with primary or secondary adrenal failure.

What are the characteristic signs and symptoms of acute and chronic adrenal insufficiency?

Acute adrenal insufficiency is a potentially fatal medical emergency, and the clinical features include nausea, fever, and shock, progressing to

diarrhea, muscular weakness, increased and then decreased body temperature, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia.

The cardinal signs of chronic adrenal insufficiency are weakness, fatigue, and anorexia, along with gastrointestinal complaints of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and vague abdominal pain. Other symptoms include salt craving (20% of the patients) and muscle cramps. Physical findings may comprise weight loss, hyperpigmentation, hypotension, and vitiligo. The ear cartilage may calcify in patients with long-standing adrenal insufficiency.

What criteria are used to make the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency?

The diagnosis of adrenocortical insufficiency is based primarily on the plasma cortisol determinations made during the rapid ACTH stimulation test (Cortrosyn test). Any screening tests for adrenal insufficiency must include determination of a basal level of cortisol and ACTH, together with a rapid ACTH stimulation test. This test is performed by administering 25 units (0.25 mg) of synthetic ACTH intravenously/intramuscularly (IV or IM) and measuring the response of cortisol and aldosterone. It is performed to assess initially whether the adrenals can respond to exogenous ACTH. A clearly normal response excludes the possibility of primary and chronic, but not acute, secondary adrenal failure. For the cortisol response to be normal, the cortisol level after ACTH administration should be at least 18 ng/dL and increased by at least 9 ng/dL above the basal levels. Normally, the aldosterone levels parallel the cortisol levels, with an increase of at least 14 ng/dL above the basal levels. Patients with Addison’s disease exhibit very low cortisol levels and a clearly elevated ACTH level, whereas the levels of both tend to be low in patients with hypopituitarism. In the classic situation, the response of aldosterone to ACTH is absent in patients with primary adrenal failure, whereas it is preserved in patients with secondary adrenal failure. The measurement of aldosterone is not routine but can add diagnostic information for primary adrenal failure. A low-dose (1 μg cortrosyn) cortrosyn stimulation test is also available and may be more sensitive when appropriate cutoff values are used. However, additional technical difficulties in cortrosyn administration and timing of blood tests have prevented this test from becoming routinely accepted.

What are the considerations in deciding on long-term replacement therapy for Addison’s disease?

Long-term replacement therapy in patients with Addison’s disease involves the oral administration of a cortisone preparation in physiologic replacement doses. Usually, two thirds of the total dose is given in the morning and the remainder is given in the evening to mimic the normal circadian secretion of cortisol. Cortisone acetate can be taken as a dose of 25 mg in the morning and 12.5 mg in the evening. Alternatively, hydrocortisone can be taken in a dosage of 30 to 40 mg per day. However, because cortisone must be converted to hydrocortisone in the body, hydrocortisone is considered the more physiologic agent. Despite this, prednisone (5–7.5 mg per day) is frequently prescribed for long-term replacement because it costs less than hydrocortisone. The side effects from the excessive administration of the above

glucocorticoids include increased appetite, weight gain, insomnia, edema, and hypertension.

Mineralocorticoid replacement (fluorohydrocortisone therapy) is necessary in patients with primary Addison’s disease, although the exact replacement dose must be titrated to the patient’s response. Dramatic fluid retention may occur with the initial treatment, but this subsides once the dose is adjusted.

What other metabolic abnormalities may occur in association with adrenal insufficiency?

Hyperkalemia occurs frequently in patients with primary adrenal failure (approximately 64%). This is largely due to renal tubular absorption of potassium at the expense of sodium stemming from the mineralocorticoid deficiency. In addition, glucocorticoids help in maintaining the function of the sodium pump and the normal gradient between the intracellular and extracellular concentrations of sodium and potassium. Without cortisol, this gradient is not maintained, so that potassium moves out of the cell and sodium moves into the cell, thereby resulting in hyperkalemia. Of note, in patients with secondary (pituitary) adrenal insufficiency, the mineralocorticoid axis is intact and hyperkalemia, arising from the second mechanism only, is mild or absent.

Hypoglycemia occurs infrequently, and primarily in patients with Addison’s disease who have fasted for any period. It is due to defective gluconeogenesis.

A mild acidosis may eventuate in patients with mineralocorticoid deficiency because of the decreased secretion of ammonia and hydrogen ions.

Circulating levels of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) may increase and contribute to the hyponatremia. The excessive loss of sodium by the renal tubules leads to an increased water loss. This is counterbalanced by an increase in the ADH levels, which tends to cause water retention. The low cardiac output and hypovolemia also serve as stimuli for ADH release.

The inability to excrete a water load was once used as a diagnostic test for Addison’s disease. This phenomenon is primarily caused by glucocorticoid deficiency, even in the presence of euvolemia. A bolus of cortisol completely reverses the effect and a “water diuresis” ensues, but this also involves the interplay of other factors, such as an improvement in cardiac output, an increase in the effective circulating volume, an increase in the glomerular filtration rate, a reduction in ADH levels, and direct effects on the renal tubule.

Peripheral eosinophilia is a common finding in the setting of primary adrenal insufficiency.

What are the events that take place in the regulation of cortisol secretion by the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis?

Adrenocortical cell growth and steroid secretion are primarily controlled by the pituitary hormone ACTH. The secretory regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis involves the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) by the hypothalamus into the hypophyseal portal system. This hormone causes the pituitary secretion of ACTH, which is transported by the peripheral circulation to the adrenal glands, where it is bound by

specific receptors and triggers steroid synthesis and secretion. Cortisol inhibits both CRH and ACTH release, whereas ACTH has a negative feedback effect on CRH release. Hormonal and neural input from higher brain centers stimulates or inhibits CRH synthesis and secretion in a 24-hour cycle, which causes both ACTH and cortisol secretion to exhibit a circadian rhythm. The circadian rhythm can be overcome by stress, however, leading to chronic cortisol synthesis. Cortisol circulates bound to cortisol-binding globulin (transcortin) and the free cortisol enters a cell and interacts with a specific receptor to exert its physiologic effects.

What are the specific causes of primary and secondary adrenal failure?

Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease) is most commonly caused by idiopathic adrenal atrophy stemming from autoimmune destruction (68%), tuberculosis (17%), or some other etiology (15%). Ninety percent of the gland must have been destroyed before Addison’s disease becomes apparent. Less common causes of adrenal insufficiency include other granulomatous diseases, such as histoplasmosis and sarcoidosis, or infiltrative diseases, such as amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, metastatic tumor, and adrenal leukodystrophy, as well as chronic anticoagulation and bilateral adrenal hemorrhage. Gram-negative septicemia, bilateral adrenalectomy, abdominal irradiation, adrenal vein thrombosis, adrenal artery embolus, and adrenolytic drugs are also rare causes of adrenal failure.

Adrenal insufficiency is found in some patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The main presentation of adrenal insufficiency in AIDS is fatigue; electrolyte abnormalities are uncommon. Development of adrenal insufficiency in patients with at least one AIDS-defining disease is associated with poor prognosis.

Secondary adrenal insufficiency is commonly caused by iatrogenic corticosteroid therapy, which suppresses CRH and ACTH secretion and results in adrenal atrophy. Other, less common causes include pituitary and hypothalamic tumors, irradiation, trauma, pituitary necrosis, and lymphocytic hypophysitis surgical procedures.

Case

A 60-year-old man is hospitalized because of severe nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea of 4 days’ duration. He admits to having experienced mild increasing fatigue and malaise for the last 6 months plus poor appetite, frequent abdominal cramps, and a 20-lb (9-kg) weight loss over the last 4 months. He feels dizzy in the morning and lightheaded after standing for more than an hour. He notes that he tends to take a nap in the late afternoon. Four days before presentation, abdominal cramps, vomiting, and diarrhea developed. He denies any skin changes and prolonged sun exposure. He admits to a decline in sexual desire. He has no history of hypertension, diabetes, asthma, or tuberculosis, and takes no medications.

Physical examination reveals a very tanned man, who appears acutely ill and somewhat dehydrated. He weighs 63 kg. His supine blood pressure (BP) is 106/68 mm Hg and his supine pulse is 90 beats per minute; his standing BP is 80/50 mm Hg and his standing pulse is 104 beats per minute.

His skin shows decreased turgor. His face, hands, extensor surfaces, chest, and back are notably tanned. The findings from the head, eyes, ear, nose, and throat examination are normal, except for the presence of hardened earlobes. No heart abnormalities are noted and his lungs are clear. Abdominal examination reveals the presence of diffuse tenderness, but no rebound or localized tenderness. The bowel sounds are hyperactive. There is decreased axillary hair. His testes are normal and central nervous system findings are unremarkable.

The following laboratory data are obtained: hemoglobin (Hgb), 10.6 g, normochromic normocytic anemia; white blood cell (WBC) count, 6,600 cells/mm3; sodium, 128 mEq/L; potassium, 5.9 mEq/L; creatinine, 2.0 mg/dL; bicarbonate (HCO3–), 20 mEq/L; chloride, 96 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 39 mg/dL; and calcium, 11.1 mg/dL.

The chest radiographic study findings are normal and the abdominal radiographic study shows a normal gas pattern, but bilateral adrenal calcification. His electrocardiogram (ECG) is normal.

Seven months later, the patient becomes severely fatigued and weak and complains of cold intolerance, dry skin, somnolence, and constipation. Physical examination at that time reveals a pale patient, with a supine BP of 110/60 mm Hg and supine pulse of 64 per minute. He weighs 72 kg. His skin is dry and warm and exhibits decreased turgor. Periorbital freckling and vitiligo are present, as well as mild, diffuse thyromegaly. Neurologic examination reveals generalized muscle weakness and decreased deep tendon reflexes symmetrically.

Laboratory data are as follows: WBC, 6,900 cells/mm3 with normal differential; serum sodium, 135 mEq/L; potassium, 4.7 mEq/L; chloride, 99 mEq/L; HCO3–, 24.8 mEq/L; glucose, 78 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.0 mg/dL; and BUN, 18 mg/dL. Thyroid function tests reveal the following findings: serum thyroxine (T4), 3.2 μg/dL (normal, 4 to 12 μg/dL); triiodothyronine (T3) resin uptake, 20% (normal, 25% to 35%); and TSH, 16 μU/mL (normal, 0.55.0 μU/mL). The test result for antimicrosomal antibodies is positive, with a value of 1:50,000.

What is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

What would be the first step in the diagnostic evaluation of this patient?

On the basis of the findings from the initial diagnostic evaluation, what is the diagnosis in this patient?

What would you recommend as an initial therapy?

How would you treat this patient’s hypercalcemia?

What additional abnormalities may be seen in association with Addison’s disease?

On the basis of the findings when the patient is seen 7 months later, what kind of thyroid disease does he have?

What is the most important advice to give this patient?

Case Discussion

What is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

The most likely diagnosis in this patient is acute adrenal insufficiency resulting from either primary or secondary adrenal failure. This patient illustrates the

nonspecific nature of symptoms in the setting of chronic adrenal insufficiency, even though he exhibits the classic history and findings.

This patient’s hyperpigmentation and electrolyte changes suggest primary adrenal failure. The hyperkalemia and hyponatremia are due to mineralocorticoid deficiency, often seen in the setting of primary adrenal failure. Because ACTH is not the predominant regulator of aldosterone secretion, electrolyte abnormalities are less common in patients with secondary adrenal failure.

Adrenal crisis occurs when a stressful situation brings about decompensation. The nature of the stress may range from mild (e.g., the flu) to severe (e.g., trauma or surgery). Adrenal decompensation is marked by dehydration, hypovolemia, profound hypotension, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, and hypothermia. Classic renal failure can mimic several aspects of chronic adrenal failure, including fatigue, malaise, anorexia, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia. In this patient, the BUN and creatinine abnormalities are more indicative of prerenal azotemia than of acute renal failure.

Decreased libido, which is common in patients with hypopituitarism, can also be seen in patients with Addison’s disease and is due to the debilitating nature of the illness, the associated primary gonadal failure, and possibly the decreased adrenal androgens.

Calcification of the auricular and costal cartilage is uncommon in patients with Addison’s disease, but can occur incidentally. A lack of axillary hair is actually a more common finding in female patients. The amount of pubic hair may also be diminished.

What would be the first step in the diagnostic evaluation of this patient?

The ACTH stimulation test should be performed initially to assess whether the adrenal glands can respond to exogenous ACTH by increasing the levels of cortisol and aldosterone. Simultaneously, the plasma ACTH level should be measured because patients with Addison’s disease have very low cortisol levels but elevated ACTH levels. It is critical to have the laboratory process the samples correctly (check with your laboratory to determine the appropriate process for blood collection). Adrenal autoantibody testing is now available and has a 70% sensitivity. In addition, because of the abdominal radiographic finding of adrenal calcification, a purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test should be performed to assess for tuberculosis.

An ACTH stimulation test reveals a basal cortisol level of 2.8 μg/dL, which is then 2.8 μg/dL at 30 minutes and 3.0 μg/dL at 60 minutes. The aldosterone level is 2.5 ng/mL at 0 minutes, 2.5 ng/mL at 30 minutes, and 3.1 ng/mL at 60 minutes (normal values—cortisol, 9 to 25 μg/dL a.m. fasting, and 2 to 16 μg/dL p.m. fasting; aldosterone, normal salt upright: men, 6 to 22 ng/dL; women, 4 to 31 ng/dL). The plasma ACTH level is found to be 779 pg/mL (normal, <580 pg/mL at 8:00 a.m. upright; 526 pg/mL at 8:00 a.m. supine; and <517 pg/mL at 4:00 p.m. supine). The PPD test result is negative.

On the basis of the findings from the initial diagnostic evaluation, what is the diagnosis in this patient?

The results of the ACTH stimulation test in this patient are clearly abnormal, showing subnormal responses to ACTH—indicative of adrenal failure. This is the

classic situation in patients with primary adrenal failure, that is, the response of both cortisol and aldosterone to ACTH is absent; in secondary adrenal failure, the aldosterone response is preserved.

The plasma ACTH level is markedly elevated in this patient, and such extreme elevations may be seen in the context of severe stress, such as that caused by surgery, anesthesia, and hypoglycemia. Calcification of the adrenal glands can occur in the setting of tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, and occasionally in autoimmune adrenal disease. Therefore, the cause of this patient’s adrenal gland failure is primary adrenal failure, most likely secondary to the autoimmune destruction of the adrenals. The negative PPD result supports a nontuberculous etiology of the primary adrenal failure.

What would you recommend as an initial therapy?

Because the clinical presentation suggests adrenal crisis, therapy should be instituted immediately because adrenal crisis is a life-threatening emergency and any delay in treatment could prove fatal. Such therapy includes the immediate IV administration of a soluble corticosteroid preparation, such as hydrocortisone (100 mg), followed by rapid infusions of glucose and normal saline at a rate of 2 to 4 L per day. For true crisis, large volumes (2 to 3 L) of 0.9% saline solution or 5% dextrose in 0.9% saline should be infused intravenously as quickly as possible.

The glucocorticoids and volume repletion cause the serum potassium levels to decrease. Definitive diagnostic testing should be carried out after the acute therapy has been instituted. Mineralocorticoid therapy should be deferred until the patient can take medication orally.

How would you treat this patient’s hypercalcemia?

Because this patient’s hypercalcemia is mild, no special treatment other than hydration with normal saline is required. Both hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia have been reported to occur during an adrenal crisis. This may stem from dehydration, but may also be a consequence of the increased absorption of calcium from the gut, due to glucocorticoid deficiency. Occasionally, mild hypercalcemia and hyperparathyroidism may coexist with adrenal failure caused by a pituitary tumor that compromises the function of corticotrophs [multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1)]. Hypocalcemia may occur in patients whose hypoadrenalism is a part of the autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type I (polyglandular failure).

What additional abnormalities may be seen in association with Addison’s disease?

Other abnormalities that may arise in patients with Addison’s disease include hypoglycemia, hyperkalemia, high ADH levels, metabolic acidosis, vitiligo, and high levels of antithyroid antibodies. All of these can be a frequent component of the clinical picture in patients with adrenal insufficiency.

On the basis of the findings when the patient is seen 7 months later, what kind of thyroid disease does he have?

The findings are consistent with those of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Patients with idiopathic Addison’s disease are prone to other autoimmune disorders, which may develop before or after adrenal failure is diagnosed. These disorders include Graves’ hyperthyroidism, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, pernicious anemia, diabetes, hypoparathyroidism, primary hypogonadism, vitiligo, and moniliasis. Areas of vitiligo

form in 4% to 6% of the patients with Addison’s disease, especially in those whose disease has an autoimmune cause.

In this man who has a goiter, low T4 and high TSH levels, and strongly positive antithyroid antibody titers, levothyroxine therapy should be started, but only when adequate steroid replacement has been achieved and after the patient has been on steroid replacement therapy for at least 2 weeks. An adrenal crisis could be precipitated if levothyroxine is given to a patient who is in a hypoadrenal state because of the resulting increased metabolic demands that levothyroxine imposes on the body.

What is the most important advice to give this patient?

In any patient with adrenal insufficiency, it is critical to emphasize the need for increasing the dosage of glucocorticoids during periods of stress or illness, such as colds, flu, diarrhea, infections, trauma, or surgery. Failure to do so might precipitate the rapid development of an acute adrenal crisis. In addition, the patient must be instructed to wear an identification bracelet or carry a card at all times indicating that he has the disease and needs supplemental steroids during stress. This is a crucial life-preserving measure and cannot be overemphasized.

Suggested Readings

Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C, et al. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA 2002;288(7):862–871.

Arafah BM. Medical management of hypopituitarism in patients with pituitary adenomas. Pituitary 2002;5:109–117.

Knapp PE, Arum SM, Melby JC. Relative adrenal insufficiency in critical illness: a review of the evidence. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes 2004;11:147–152.

Lindsay JR, Nieman LK. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in pregnancy: challenges in disease detection and treatment. Endocr Rev 2005;26:775–799.

Nieman LK. Dynamic evaluation of adrenal hypofunction. J Endocrinol Invest 2003;26(7 Suppl):74–82.

Schrier RW. Current medical therapy, 2nd ed. New York: Raven Press, 1989.

Wilson JD, Foster DW, eds. Williams’ textbook of endocrinology, 8th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1992.

Cushing’s Syndrome

What is the difference between Cushing’s syndrome and Cushing’s disease?

What is the most common cause of Cushing’s syndrome?

What are the clinical features of Cushing’s syndrome?

What are the biologic effects of glucocorticoids?

What are the screening tests used to diagnose Cushing’s syndrome?

Discussion

What is the difference between Cushing’s syndrome and Cushing’s disease?

Cushing’s syndrome refers to the phenotypic and clinical sequelae due to hypercortisolism resulting from any cause. Cushing’s disease refers specifically to the hypercortisolism due to an ACTH-secreting pituitary corticotroph adenoma or pituitary corticotroph hyperplasia.

What is the most common cause of Cushing’s syndrome?

The widespread use of potent corticosteroids in the practice of clinical medicine, particularly in the treatment of autoimmune, allergic, and pulmonary disorders, has made iatrogenic hypercortisolism the most common cause of Cushing’s syndrome. However, once the iatrogenic causes are eliminated, pituitary adenoma (68%) becomes the most common cause.

What are the clinical features of Cushing’s syndrome?

Cushing’s syndrome is associated with many clinical features. Obesity, found in 94%, is the most common manifestation and weight gain is usually the earliest symptom of Cushing’s syndrome. The obesity tends to be central, but fat can also be redistributed to the face (moon facies; 75%), as well as supraclavicular (80%) and dorsocervical areas (“buffalo hump”; 80%). The latter two areas, particularly the supraclavicular fat pad, are more specific findings for Cushing’s syndrome.

Skin changes occur in 85% of the patients and arise because cortisol-induced atrophy of the epidermis leads to thinning and a transparent appearance of the skin, facial plethora, easy bruisability, and the formation of striae. The latter are purplish red areas that are depressed below the skin surface, but are wider than the pinkish white striae that appear after pregnancy or weight loss. Wounds heal slowly in these patients and may dehisce. Hyperpigmentation occurs in the setting of the ectopic ACTH syndrome, but is rare in patients with Cushing’s disease and should not be found in those with primary adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. Acne (40%) is also a symptom and is due to androgen excess; it may be more generalized than what the patient experienced before.

Hirsutism affects 80% of the patients and typically consists of a darkening and coarsening of the hair. Female patients complain of increased growth of hair over the face, upper thighs, abdomen, and breasts. Virilism occurs in approximately 20% of the cases of adrenal carcinoma. Hypertension is a problem in 75% of the patients. Elevated diastolic BP is a classic feature of spontaneous Cushing’s syndrome, and it contributes greatly to the morbidity and mortality associated with the disorder. The increased sodium retention also leads to edema (18%). Congestive heart failure (22%) can be aggravated because of the increased BP and fluid load.

Gonadal dysfunction occurs in 75% of the patients. Elevated androgen levels can result in amenorrhea and infertility in 75% of affected premenopausal women. In men, the elevated cortisol level may cause a decrease in libido.

Muscle weakness arises in 60% of patients, in particular proximal weakness that most often occurs in the lower extremities. This weakness stems from the catabolic effects of glucocorticoids on muscle tissues, steroid-induced myopathy, and possibly electrolyte imbalances. Weakness can be assessed clinically by asking the patient to stand from the chair without assistance of arms. Radiographically detectable osteoporosis is present in most patients with Cushing’s syndrome (60%), and back pain is the initial complaint in 58% of the cases. Pathologic fractures are found in the ribs and vertebrae in severe cases. It takes some time for the hypercortisolism to decalcify bone; therefore, Cushing’s syndrome due to adrenal carcinoma and some ectopic ACTH cases is not present long enough to cause osteoporosis.

Psychological disturbances can arise in 40% of patients. These complaints range from mild symptoms, such as emotional lability, increased irritability, anxiety, insomnia, euphoria, poor concentration, poor memory, and mild depression, to severe symptoms, which include frank psychosis associated with delusions or hallucinations, paranoia, severe depression, and even suicidal behavior.

Renal calculi form in 15% of patients as a result of glucocorticoid-induced hypercalcemia. Renal colic may be the presenting symptom of Cushing’s syndrome. Thirst and polyuria are seen in 10% of patients. The thirst is due to glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia [or worsening of existing diabetes mellitus (DM)] that causes an osmotic (glucose) diuresis. Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and diabetic microvascular complications are rare in the diabetes seen with Cushing’s syndrome.

What are the biologic effects of glucocorticoids?

From a molecular perspective, glucocorticoid hormones enter the cell by diffusion and activate specific gene transcription by binding to the nuclear glucocorticoid receptor. The glucocorticoid receptor is therefore a conditional transactivator that influences the rate of RNA polymerase II transcription initiation by binding to specific short DNA sequence elements (glucocorticoid response elements) in the promoter regulatory region of the various target genes. Although this is the best-established pathway of glucocorticoid action, other mechanisms that mediate the rapid effects of glucocorticoids, such as the fast-feedback inhibition of ACTH secretion and possibly modulation of the γ-aminobutyric acid receptor, must also exist.

In terms of their effects on metabolism, glucocorticoids accelerate hepatic gluconeogenesis by stimulating phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose-6-phosphatase activity, and induce a permissive effect in other gluconeogenic hormones (glucagon and catecholamines). Glucocorticoids also enhance hepatic glycogen synthesis and storage and inhibit glycogen breakdown. In muscles, glucocorticoids inhibit amino acid uptake and protein synthesis and stimulate protein breakdown as well as the release of amino acids, lactate, free fatty acids (FFAs), and glycerol. In adipose tissue, glucocorticoids primarily accelerate lipolysis, with a resultant release in the formation of glycerol and FFAs. Although glucocorticoids are lipolytic, an increased central fat deposition is a

classic feature of Cushing’s syndrome. The steroid-induced increase in appetite and hyperinsulinemia may account for this, but the basis for this abnormal fat deposition in the setting of hypercortisolism remains unknown.

What are the screening tests used to diagnose Cushing’s syndrome?

A key aspect of the initial workup in a patient with suspected Cushing’s syndrome is to distinguish true hypercortisolism from obesity, depression, or alcoholism, or a combination of these, because many clinical and laboratory features of these disorders display significant overlap. A key aid in establishing the clinical diagnosis of hypercortisolism is examining the patient’s sequential photographs that span several years. Once Cushing’s syndrome is suspected on clinical grounds, the overnight 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test (DST) and the 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC) determination are used as screening tests. If the results of the overnight 1-mg DST are normal (8 a.m. plasma cortisol <2 μg/dL after the administration of 1 mg of dexamethasone at 11 p.m. the night before), the diagnosis is very unlikely. If the results of the UFC test are also normal (i.e., <90 to 100 μg per day), Cushing’s syndrome is effectively excluded. A third, recently available, but not yet widely accepted screening test is the late night salivary cortisol. This test takes advantage of the loss of normal circadian variation in cortisol level in Cushing’s disease by measuring cortisol at a time when it is normally virtually absent. Several situations can cause false-positive results for the screening DST, including acute and chronic illness, obesity, high-estrogen states, certain drugs (phenytoin and phenobarbital), alcoholism, anorexia, renal failure, and depression. However, in the setting of obesity, high-estrogen states, and certain drugs, the results of a 24-hour UFC are normal. In the other situations, repeated testing is necessary to exclude the diagnosis. Rarely false-negative results can occur, such as in the event of prolonged dexamethasone clearance or episodic hypercortisolism.

Case

A 36-year-old white woman comes to you complaining of fatigue, irritability, depression, and a 30-lb (13.5-kg) weight gain over the last 2 years. She recounts that she has noticed a significant change in her energy level for at least the last 2 years. She states that she has always been a hard worker but 6 months before she had to quit her job as a waitress because of extreme muscle weakness and fatigue. She has also noted increased mood swings, manifested by increased irritability, spontaneous crying episodes, and depression. She reports that her face seems rounder than it was 2 years before. On further questioning, she admits that her menstrual periods have been irregular for the last 2 years. She also admits to drinking “a six-pack of beer” at least once a week, but denies smoking. She has also noted that she bruises easily. She denies any other medical problems, and states that she is not taking any medications. She specifically denies any glucocorticoid therapy. On asking about her family history, you find out that her mother has adult-onset DM.

Physical examination reveals an obese white woman who is crying while she sits on the examining table, but otherwise she does not appear to be very ill. Her weight is 193 lb (87 kg); height, 5 ft 7 in. (167.5 cm); BP, 165/100 mm Hg; and heart rate, 86 per minute and regular.

Her face is very round and plethoric compared with that in old photographs. Dorsocervical (buffalo hump) and supraclavicular fat pads are noted. She has mild facial hirsutism, some acne is noted over the face and chest, and wide purple striae are present on the lower abdomen. Her extremities are thin and she has proximal muscle weakness.

The following are the laboratory findings: fasting blood glucose, 180 mg/dL; potassium, 3 mEq/L; HCO3–, 34 mEq/L; liver function tests, all normal; 8 a.m. cortisol, 38 μg/dL, which decreases to 32 μg/dL after the administration of 1 mg of dexamethasone. The 24-hour UFC level is 876 μg.

What is the most likely diagnosis in this patient, and why?

What studies would you perform to establish the anatomic cause of her hypercortisolism?

What is the role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomographic (CT) scanning of the pituitary and adrenal glands, as well as inferior petrosal sinus sampling, in patients with Cushing’s syndrome?

What is the optimal therapeutic approach for this patient?

Why is there a need for steroid therapy in the postoperative period, and sometimes beyond, in patients with Cushing’s disease?

Case Discussion

What is the most likely diagnosis in this patient, and why?

Having excluded exogenous glucocorticoid medications in the history, the differential diagnosis list would include (a) pituitary corticotroph adenoma or hyperplasia (Cushing’s disease), (b) ectopic ACTH or corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) syndrome, (c) adrenal adenoma, (d) adrenal cancer, (e) obesity, (f) depression, and (g) alcoholism.

The most frequently encountered dilemma in the differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome is the clinical picture consisting of an obese, depressed patient who consumes excessive amounts of alcohol. These patients can display many of the phenotypic features and laboratory findings consistent with hypercortisolism, and yet not have Cushing’s syndrome. Therefore, the patient’s history of consuming a six-pack of beer per week is of concern because this could produce alcoholic pseudo-Cushing’s syndrome. In this disorder, the effects of chronic alcoholism result in central obesity (ascites), a round plethoric face, easy bruising, and some abnormal results from the screening tests for Cushing’s syndrome. However, this patient has no abnormal liver function findings and she has physical findings (a marked change in her facial appearance compared with that in old photographs, hypertension, dorsocervical and supraclavicular fat pads, purple abdominal striae, acne, and hirsutism) and laboratory data (hyperglycemia, hypokalemia, an elevated basal cortisol level that does not suppress in response to the 1-mg DST, and an elevated 24-hour UFC) that are all highly consistent with the clinical suspicion of hypercortisolism.

The lack of virilization and the relatively slow (>2 years) onset of the clinical symptoms argue against adrenal carcinoma. In addition, the lack of a smoking history and any hyperpigmentation, together with the slow onset, suggest that

ectopic ACTH arising from small cell lung carcinoma is unlikely to be the cause. This leaves pituitary adenoma (or hyperplasia), ectopic ACTH or CRF (from a carcinoid, pancreatic islet cell tumor, medullary thyroid carcinoma, or pheochromocytoma), and adrenal adenoma in the differential diagnosis. Given that pituitary adenomas constitute 68% of all noniatrogenic causes of hypercortisolism, this is the most likely diagnosis. However, further workup is required to document the precise source of the elevated cortisol levels in this patient.

What studies would you perform to establish the anatomic cause of her hypercortisolism?

Once the diagnosis of hypercortisolism (Cushing’s syndrome) has been confirmed by the findings of the clinical evaluation and screening laboratory tests, the combined use of the following diagnostic techniques can establish the diagnosis in almost all instances: determination of a basal plasma ACTH level, a high-dose (8 mg) DST, radiographic imaging, and inferior petrosal sampling (with or without CRF stimulation). By simultaneously measuring the plasma cortisol and ACTH levels the possibility of an adrenal adenoma can be assessed because the autonomous production of glucocorticoids by the adrenal adenoma suppresses ACTH to levels below 20 pg/mL. To differentiate between a pituitary adenoma and the ectopic tumor production of ACTH, several tests need to be performed because many of the laboratory and radiographic results can overlap for these two distinct causes of Cushing’s syndrome. For example, the ACTH level can range between 40 and 200 pg/mL in the setting of Cushing’s disease and between 100 and 10,000 pg/mL in the setting of ectopic ACTH. In the classic 2-day high-dose DST (2 mg of dexamethasone is given every 6 hours for 2 days, and 24-hour UFC samples are collected the day before and on the second day of dexamethasone administration), patients with pituitary tumors (Cushing’s disease) typically exhibit a suppression to less than 50% of baseline values; those with ectopic ACTH or primary adrenal hypercortisolism display little or no reduction. However, some carcinoid tumors that produce ACTH ectopically maintain some degree of negative feedback through the influence of exogenous steroids, and the suppression observed may be equivalent to that seen in patients with pituitary tumors.

The abbreviated high-dose DST involves administering 8 mg of dexamethasone at 11 p.m. the night before and measuring the plasma cortisol level the next morning at 8 a.m. In this test, a suppression below 50% of basal plasma cortisol levels is seen in patients with pituitary tumor, but not in those with ectopic ACTH and primary adrenal cortisolism. This version of the high-dose DST is preferred because it appears to be more specific and does not require two 24-hour urine collections. For a more precise definition of the cause of the disorder, however, specific radiographic procedures must be performed.

What is the role of MRI and CT scanning of the pituitary and adrenal glands, as well as inferior petrosal sinus sampling, in patients with Cushing’s syndrome?

The major problem with the CT and MRI evaluation of the pituitary and adrenal glands is that they can detect asymptomatic lesions in up to 15% and 8%, respectively, of the normal population. Because of this incidence of nonspecific radiographic “lesions”, the clinician must be cautious about basing the diagnosis of pituitary or adrenal Cushing’s syndrome on the results of these imaging studies.

Pituitary adenomas causing Cushing’s disease tend to be small (1 to 5 mm; rarely >10 mm), and are therefore detectable by contrast-enhanced CT scanning in as few as 30% to 35% of cases and by gadolinium–DTPA-enhanced MRI in 55% of cases. Therefore, because of its better sensitivity, MRI has replaced CT in the assessment of these tumors. Patients whose imaging studies yield negative findings need to undergo inferior petrosal sampling to further document the pituitary anatomic location of the tumor. In addition, as already discussed, even if an abnormality is detected by these imaging methods, this does not constitute unequivocal evidence that the abnormality is responsible for the syndrome. As the resolution of CT and MRI improves, the ability to detect these “incidental” and clinically silent microadenomas will also increase and further confound the diagnostic workup. An ectopic CRF syndrome could also result in an enlarged pituitary due to corticotroph hyperplasia, and yet the primary disorder may actually be a carcinoid of the lung.

CT, MRI, ultrasonography, and isotope scanning with iodocholesterol can be used to define the nature of adrenal lesions. These procedures are not necessary in patients with ACTH hypersecretion, however. Nevertheless, some physicians use these tests to exclude the presence of a solitary adrenal adenoma or carcinoma, and thereby confirm the presence of bilateral adrenal hyperplasia or nodular adrenal hyperplasia in the setting of pituitary-based disease. These procedures are most useful for localizing adrenal tumors because these tumors must usually be larger than 1.5 cm to cause significant cortisol production and result in Cushing’s syndrome. However, as noted previously, because of the 1% to 8% incidence of silent adrenal nodules biochemical testing must be performed with localization studies to ensure that the lesion identified is biologically significant.

To distinguish between the various causes of Cushing’s syndrome when conflicting or overlapping data are obtained, bilateral simultaneous inferior petrosal venous sampling (with or without CRF stimulation) can successfully distinguish Cushing’s disease from ectopic ACTH secretion and adrenal disease with greater accuracy than any other test. Because ACTH is rapidly metabolized (half-life, 7 to 12 minutes) and is secreted episodically, advantage can be taken of the concentration gradient between the pituitary venous drainage through the inferior petrosal sinus (central) and the peripheral venous values of ACTH to further determine whether an ACTH-producing corticotroph adenoma is present in the pituitary; the inclusion of CRF stimulation makes the test more sensitive. Bilateral and simultaneous inferior petrosal sinus samples are obtained to circumvent the problem of isolated secretory bursts or timing issues if catheters have to be repositioned. Therefore, ACTH samples are obtained from the inferior petrosal sinus, from the jugular bulb, and from other sites (e.g., superior or inferior vena cava), and the findings are compared with those from simultaneously obtained peripheral vein samples. In patients with Cushing’s disease, the inferior petrosal sinus/peripheral (IPS : P) ratio of ACTH exceeds 2. In patients with ectopic ACTH, the ratio is less than 2 and selective venous sampling (e.g., of the pulmonary, pancreatic, or intestinal beds) may localize the ectopic tumor. The administration of CRF during bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling can increase the diagnostic accuracy of the test by eliciting

an ACTH response in the few patients with pituitary tumors who do not exhibit a diagnostic IPS : P gradient in the basal samples. Most patients with Cushing’s disease have an IPS : P ratio greater than 3 after CRF stimulation, whereas patients with ectopic ACTH or adrenal disease have an IPS : P ratio of ACTH less than 3 after CRF stimulation. Inferior petrosal sinus sampling (with or without CRF stimulation) has not been extensively studied in the context of healthy people, however, and therefore the correct interpretation of the results requires that the patient must be hypercortisolemic at the time of the study so that the response of normal corticotrophs to CRF is suppressed.

What is the optimal therapeutic approach for this patient, and why?

Once the tumor has been localized to the pituitary, the next goal is to surgically remove the corticotroph adenoma using the technique of selective transsphenoidal surgery. Because the tumors are small, it requires an experienced neurosurgeon to successfully identify and resect the adenoma. Meticulous exploration of the intrasellar contents is mandatory, and any identified adenoma is selectively removed, leaving the remaining normal pituitary intact. If the tumor cannot be identified, it is necessary to perform larger pituitary resections and, in some cases, a total hypophysectomy may be necessary. Transsphenoidal surgery is successful in approximately 85% of patients with microadenomas (tumor <10 mm), and surgical damage to the normal anterior pituitary is rare. The major side effects of the procedure include transient diabetes insipidus, cerebrospinal fluid leak, sinusitis, and, rarely, postoperative bleeding. All patients with Cushing’s disease who are successfully treated with transsphenoidal surgery become adrenally insufficient for variable periods of time and must receive replacement doses of glucocorticoids (see question 5 which follows).

The success rates for transsphenoidal surgery drop drastically (15% to 25%) in the setting of large (>10 mm) tumors, locally invasive tumors, tumors not identified at surgery, and corticotroph hyperplasia. In these instances, adjunctive radiation therapy is usually administered. However, the major problem with radiation therapy is the lag time (6 to 12 months) for it to take effect and the 10% to 20% incidence of hypopituitarism and visual field deficits, even blindness, that may eventuate. A newer option is the more precise stereotactic radiosurgery using the gamma knife or photon knife. Risk of visual complications is largely eliminated, and the risk of pituitary deficiency is reduced.

Why is there a need for steroid therapy in the postoperative period and beyond, in patients with Cushing’s disease?

The successful surgical removal of the ACTH-producing pituitary microadenoma eliminates the drive for adrenal glucocorticoid production and renders the patient dependent on the remaining normal corticotrophs. However, because these cells have been suppressed for years by the excess cortisol they are dormant. Therefore, those patients with Cushing’s disease who have been successfully treated experience transient (1 to 18 months) adrenocortical insufficiency and require exogenous glucocorticoid support; in those patients not cured by the surgical procedure, the production of excessive amounts of glucocorticoids continues and they do not depend on an exogenous source of steroids.

Suggested Readings

Felig P, Baxter JD, Broadus AE, et al. eds. Diseases of the anterior pituitary. In: Endocrinology and metabolism, 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1987.

Findling JW, Raff H. Screening and diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2005;34:385–402.

Mansmann G, Lau J, Balk E, et al. The clinically inapparent adrenal mass: update in diagnosis and management. Endocr Rev 2004;25(2):309–340.

Newell-Price J, Trainer P, Besser M, et al. The diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome and pseudo-Cushing’s states. Endocr Rev 1998;19:657.

Schuff KG. Issues in the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome for the primary care physician. Prim Care Office Pract 2003;30:791–799.

Tyrrell JB, Ron DC, Forsham PH. Glucocorticoids and adrenal androgens. In: Greenspan FS, ed. Basic and clinical endocrinology, 3rd ed. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1991.

Xiao XR, Ye LY, Shi LX, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adrenal tumours: a review of 35 years’ experience. Br J Urol 1998;82:199.

Diabetes Mellitus

What are the clinical manifestations of DM?

What are the major types of DM and what are their distinguishing features?

What are the major acute and chronic complications of the disease?

What aspects of the medical history require special emphasis?

What aspects of the physical examination require special attention?

What laboratory tests are essential in the evaluation of the patient with suspected diabetes?

What are the goals of diabetes therapy and what treatment modalities are available? How should these be individualized?

Discussion

What are the clinical manifestations of DM?

DM is a complex metabolic disorder characterized by abnormalities of carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism resulting either from a deficiency of insulin or from target tissue resistance to its cellular metabolic effects. It is the most common endocrine-metabolic disorder and affects an estimated 22 million people in the United States, with the incidence of new cases increasing by more than 700,000 per year.

Diabetes is manifested by the finding of hyperglycemia and the time-dependent development of chronic complications (retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy, and accelerated atherosclerosis) resulting from the multiple metabolic derangements. Accordingly, the presenting clinical signs and symptoms can be due to hyperglycemia or the complications of the disease, or both. In general, the major classic symptoms of polydipsia, polyuria, weight loss,

and fatigue are found in the setting of new-onset diabetes in young patients whose disease is due to insulinopenia. On the other hand, older patients with diabetes may be relatively free of symptoms for a long time. In such patients, the diabetes is first detected either incidentally or because one of its chronic complications is discovered. It is estimated that approximately one third of all the adult cases of diabetes in the United States remain undiagnosed.

What are the major types of DM and what are their distinguishing features?

The current classification (according to the National Diabetes Data Group) of DM and other categories of glucose intolerance consists of three clinical classes: (a) DM which includes type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), [previously insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) or juvenile onset diabetes], and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), [previously non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM)]; (b) impaired glucose tolerance/impaired fasting glucose; and (c) gestational DM. Of these, T1DM and T2DM represent the largest category and are discussed here in further detail. Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose are defined as an abnormality in glucose levels intermediate between normal and overt diabetes, whereas gestational DM is defined as carbohydrate intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy.

T1DM constitutes approximately 5% to 10% of all cases of diabetes and is due to insulin deficiency resulting from the autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic islet cells. Therefore, such patients are prone to ketoacidosis and are absolutely dependent on exogenous insulin to sustain life (hence the term insulin-dependent diabetes). The onset in these patients is relatively abrupt and occurs usually in youth (mean age, 12 years), although it may arise at any age and is often misdiagnosed in adults.

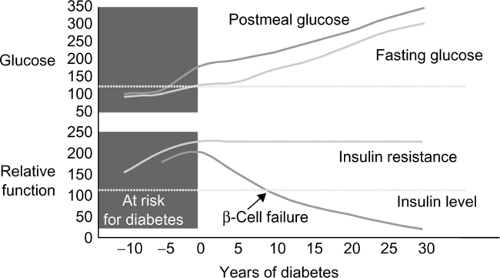

T2DM accounts for approximately 90% to 95% of all cases of diabetes. These patients have a dual impairment of insulin resistance (decreased target organ response to insulin, i.e., decreased glucose transport to muscle or ineffective suppression of hepatic glucose output) and inadequate insulin secretion to compensate for the insulin resistance. The recent obesity explosion, which is related to sedentary lifestyle and increased food intake, has exaggerated insulin resistance in susceptible people and contributed to the diabetes epidemic. Fig. 3-1 illustrates the natural history of the transition from impaired glucose tolerance to overt diabetes. T2DM is now affecting 3% to 6% of the population and occurring in younger people (even including children). There is usually a strong family history of DM in patients developing T2DM in youth.

What are the major acute and chronic complications of the disease?

DKA, hyperglycemic, hyperosmolar, nonketotic coma (HHNKC), and hypoglycemia are the major acute complications of DM. DKA is most commonly a complication of T1DM and is initiated by an absolute or relative insulin deficiency and an increase in counterregulatory hormones (glucagon, epinephrine), leading to the hepatic overproduction of glucose and ketone bodies. HHNKC is characterized by the insidious development of marked hyperglycemia, hyperosmolarity, dehydration, and prerenal azotemia in the

absence of significant hyperketonemia or acidosis. Finally, hypoglycemia can occur as an acute complication of the therapy of both T1DM and T2DM, and is the most common acute life-threatening complication of diabetes. It is most common with intensive insulin therapy, and recurrent hypoglycemia can induce a condition known as hypoglycemia unawareness, a blunting of the adrenergic and neuroglycopenic signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia. The risk of hypoglycemia unawareness can be minimized and existing unawareness treated by strict avoidance of hypoglycemia.

The most common chronic complication of diabetes and the leading cause of death for people with diabetes is cardiovascular (CV) disease. Seventy-seven percent of all hospitalizations and 80% of all mortality in diabetes is secondary to CV disease. Diabetes is an independent risk factor for CV disease. The incidence of CV events is so high in subjects with diabetes that diabetes is considered a CV risk equivalent. CV disease includes myocardial ischemia, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. People with diabetes also have an increased incidence of heart failure, which will not be addressed in this section, as the pathophysiology is poorly understood. Outcomes after acute myocardial infarction (MI) in people with diabetes are worse than controls, but can be improved with intensive glycemic control in the hospital. Interventional studies demonstrate that lipid lowering significantly decreases mortality and CV events in people with diabetes. In fact, it appears that people with DM may benefit from statins regardless of initial low-density lipoprotein (LDL). Additional large prospective trials demonstrate decreased CV mortality with intensive BP control. There is no compelling data that improvement of glycemic control affects CV morbidity or mortality except in subjects with T1DM.

Microvascular complications (retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy) are specific to diabetes and are related directly to poor glycemic control with

a smaller contribution from hypertension and dyslipidemia. Diabetes is the leading cause of blindness in the United States. By 10 years’ duration of diabetes, approximately 90% of individuals will have some degree of retinopathy. Retinopathy is largely a preventable complication of diabetes. Annual ophthalmologic examinations permit identification of individuals with progressive retinopathy. Two large multicenter studies have proved that early intervention at this stage with panretinal photocoagulation can prevent or decrease visual loss. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) established that tight glycemic control also prevents or delays retinopathy. Macular edema, corneal ulceration, glaucoma, and cataracts are additional ocular complications of diabetes.

Diabetes is the leading cause of renal failure/dialysis and transplantations nationwide. Forty percent to 60% of individuals with T1DM and 10% to 30% of individuals with T2DM will develop microalbuminuria, proteinuria, and end-stage renal disease secondary to diabetes. Hypertension and glycemic control are the primary factors that promote progression of nephropathy in people with diabetes. Normalization of BP and glucose dramatically slow the progression from incipient nephropathy (detectable microalbumin) to overt nephropathy. All people with DM should have a BP lower than 130/80 mm Hg, preferably much lower. Aggressive control of hyperglycemia (with intensive therapy) and BP [with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers] has been shown to retard the progression of nephropathy in patients with DM.

Neuropathy is a common complication of diabetes affecting more than 50% of patients with time. The most common form of nerve injury in diabetes is distal symmetric polyneuropathy, which occurs in a stocking-glove distribution; it can be painless or painful. This type of neuropathy increases the risk for traumatic foot injury and amputation. Other forms of neuropathy include: autonomic neuropathy (associated with an increased risk of CV death and hypoglycemia unawareness); mononeuritis multiplex (a vascular occlusion to a single nerve distribution that will typically recover with time); and diabetic amyotrophy (a profound, uncommon demyelinating neuromuscular wasting syndrome).

Diabetes is also associated with impaired blood flow and sensation to the extremities. This leads to a high incidence of mechanical trauma and infectious complications, leading to amputation and hospitalization. Diabetes is the most frequent cause of nontraumatic lower limb amputations. Each year, more than 56,200 amputations are performed among people with diabetes. This complication is largely preventable by appropriate footwear, regular foot examination, and education.

What aspects of the medical history require special emphasis?

A comprehensive medical history in a patient with suspected diabetes should be directed not only toward confirming the diagnosis but should also be used to review the nature of previous treatment programs and diabetes education, family history, the degree of past and recent glycemic control, and history of acute and chronic complications. Patients should also be queried

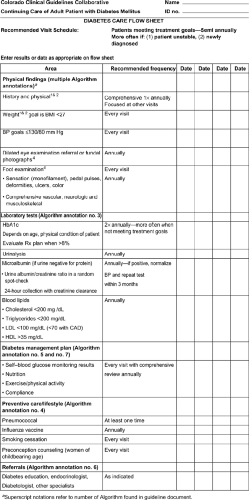

about their dietary, weight, and exercise history. Current medications for the management of diabetes, as well as other medications that may affect glycemic control, should be recorded. In addition, the presence, severity, and treatment of the acute and chronic complications of diabetes should be reviewed, including sexual function and dental care. All patients should have a careful history for diabetic health care maintenance documented at each visit. This includes glycemic control, lipid management (LDL <100, or <70 in high risk or known CV disease), BP management (<130/80 mm Hg), eye examination (annual), foot examination (each visit), diet, exercise, and self management (Fig. 3-2).

Figure 3-2 Diabetes care flow sheet. BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; CAD, coronary artery disease; HDL, high-level lipoprotein.

What aspects of the physical examination require special attention?

The vital signs are critical for patients with diabetes. BP greater than 130/80 mm Hg increases the risk for all complications, resting tachycardia suggests autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and weight gain or loss provides valuable information on severity of illness and adherence to therapy. On physical examination, dentition is important as periodontal disease can impact glycemic control and is a risk factor for atherosclerosis (chronic inflammation). Complete CV examination [including bruits and ankle brachial index (ABI)] and evaluation for edema can detect CV disease and heart failure. Loss of respiratory variation in heart rate is an early warning of autonomic neuropathy. Foot examination, including pulses and monofilament testing, can identify high-risk feet and prevent amputations. The retinal examination [undilated by a primary care physician (PCP)] is not sensitive for detection of retinopathy and needs to be done by an

ophthalmologist or by using retinal photographs. It may be conducted by the PCP, but the needed formal annual evaluation should also be arranged.

What laboratory tests are essential in the evaluation of the patient with suspected diabetes?

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and regulatory agencies have established standards for laboratory evaluation of diabetes. The diagnosis of diabetes is formally made on the basis of one of the following criteria: (a) fasting glucose 126 mg/dL or more on two occasions, (b) random glucose 200 mg/dL or more on two occasions, or (c) one abnormal reading as above together with symptoms consistent with diabetes (polyuria, nocturia, polydipsia, weight loss, blurred vision). Hemoglobin AIc (HbAIc) is not yet recommended as a diagnostic test because of a lack of standardization of existing assays, but is increasingly being considered by the ADA and regulatory agencies as a potential diagnostic tool.

What are the goals of diabetes therapy and what treatment modalities are available? How should these be individualized?

In general, the goals of diabetes therapy are (a) to alleviate the signs and symptoms of the disease (e.g., polydipsia, polyuria, and nocturia); (b) to prevent the acute complications (i.e., hypoglycemia, DKA, and HHNKC); and (c) to prevent the long-term complications of the disease (i.e., retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and atherosclerotic CV disease). The DCCT first demonstrated that tight metabolic control of T1DM leads to definite beneficial effects on the rate of complications. This also held true for patients with T2DM in the recently completed United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS). Evidence documenting the importance of glycemic control for the prevention of microvascular complication is unequivocal. Therefore, intensive glycemic control is now routine with HbAIc goals of 6.5% to 7%. The limiting factor in such attempts is an increased frequency of hypoglycemic episodes. Recent data from the DCCT follow-up study Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) now indicate that intensive control of blood glucose in T1DM also prevents macrovascular disease. In patients with T2DM, multitargeted therapy (lipid, BP, and glucose control) is the most effective strategy for CV disease prevention.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree